No one knows the Texas AirHogs quite like Larry Green. Over the team’s eleven seasons playing baseball, the 61-year-old Green has missed only five home games in Grand Prairie. On summer nights, Green pilots his Jazzy electric wheelchair to his perch on the concrete concourse behind home plate, where he cheers wildly; grumbles about how modern players spend too much time trying to hit home runs; and hollers PG invective at the home-plate umpire.

“That’s my big excitement,” Green said, taking a break between loudly questioning strike calls on an early August night. “That and trying to get these players to run out ground balls.”

The Texas AirHogs are members of the American Association of Independent Professional Baseball, a federation of twelve, mostly Midwestern, teams unaffiliated with Major League Baseball. Inning breaks are punctuated with water-balloon-toss competitions and mascot races. The level of play is good, but with more overthrows and rundowns than you’d find on an average night at a big-league ballpark. Admission starts at $8 for adults, the parking is free and convenient, and season-ticket holders like Green and his roommate, Sharen Norton, get treated like big-shots. The AirHogs’ general manager, J.T. Onyett, visits the pair every game and sometimes offers up the VIP amenities. When the temperature crept to 110 degrees earlier this summer, the AirHogs’ staff ushered Green, Norton, and a few of their friends up to a vacant air-conditioned luxury suite. “I love the Rangers,” Norton, a 62-year-old grandmother says. “But would they do that?”

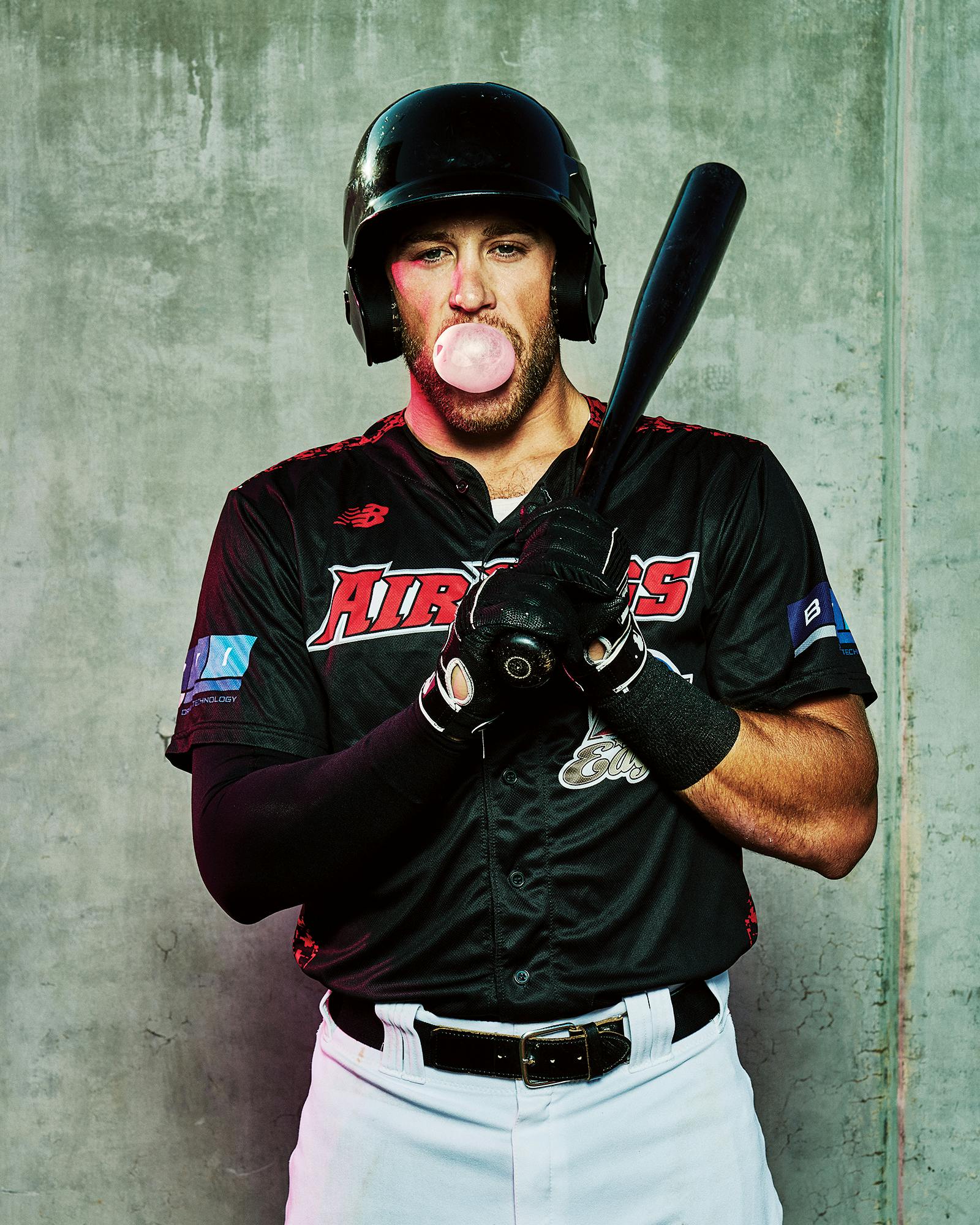

Almost everything about the AirHogs’ existence feels folksy and draped in Americana. So it came as a surprise to the team’s small group of season-ticket holders when, at a meet-and-greet with team executives before the start of the season, Onyett told them that their little hometown ball club would be undergoing a first-of-its-kind experiment. Instead of fielding a typical American Association team of fringe prospects, has-been minor leaguers, and guys trying for one last shot at The Show, the 2018 AirHogs would, in effect, lease out the majority of their roster to players from the Chinese national baseball team. Ten veteran non-Chinese pros—five pitchers and five position players—would supplement the national team squad, acting as on-field ringers and off-field mentors.

The Chinese have long been afterthoughts in Asia’s baseball pecking order, lagging well behind their athletic and political rivals Japan, South Korea, and Taiwan. Few people in China watch or play the sport; the development system is tiny, and the country has yet to produce even a high-minor-league-caliber player. (Japan, South Korea, and Taiwan have all produced major-league stars.) But with baseball returning to the summer Olympics in 2020 after a twelve-year hiatus, the Chinese government saw a reason to invest in the sport. Shipping their players to North Texas to play one hundred games against American pros would be the first big step.

When Green and Norton first heard about the impending arrival of the Chinese players, they didn’t know anything about the history of Chinese baseball. But they did know about their team in Grand Prairie. The AirHogs had won the American Association championship in 2011, but lately, they’d been more like the Bad News Bears. The team hadn’t had a winning record since 2013, they’d finished in last place two of the past four seasons, and—with barely a smattering of fans attending most home games—it sometimes seemed like they might not be able to stay in business. So when Green learned that China, a nation of 1.4 billion, was sending the “cream of the cream” of their baseball talent, he couldn’t help but get excited. Norton was even more hopeful.

“I wondered what the other teams were going to think when we started bashing the pants off them,” she said.

When the AirHogs’ season began on May 18, Green and Norton quickly recalibrated their expectations. The Chinese national team players that arrived in Texas were young, inexperienced, and far from world-beaters. “They didn’t know what was going on. They would do some things that a Little League team would do,” Green said.

But in August, watching the AirHogs take on the Sioux City Explorers seventy games into the season, Green was pleased with what he saw on the field. “They’re really jiving,” Green said. “And the Chinese guys always run it out, which I like.”

Earlier that day, the AirHogs’ Chinese players had gathered for a light morning practice of fielding drills and soft-toss, then filed into the stadium’s former sports bar and grill, which has been repurposed as the team cafeteria. A heavy aroma of dried red chili peppers, sizzling meat, and heaping quantities of dried cumin wafted from ten steamer trays.

In preparation for the season, the AirHogs’ ownership group had enlisted Gary Gao, the owner of Plano restaurant Sichuan Folk, to coordinate the team’s meals, and they’d given him the resources to go on a nationwide talent search for “A-level” Chinese chefs who would cook authentic meals before and after games. The two men sweating over the kitchen’s row of industrial-sized woks in early August both came from northern China via Los Angeles and, as lunchtime began, dozens of Chinese players waited in line for their chance to scoop generous portions of the chefs’ dry-pot chicken and braised bok choy onto their trays. (A common refrain among the AirHogs’ non-Chinese staff and players is that the cuisine is “different than what you’d get at Panda Express.”)

Catered meals, to say nothing of authentic Chinese feasts, were not the norm for the AirHogs before the 2018 season. In previous years, a Texas AirHogs player could expect at-bats, a long-shot chance at returning to minor-league ball, and basically nothing else. Salaries in the American Association are meager to modest. (Three-thousand per month is a star’s wages, and most players make closer to the $1,300-per-month league minimum.) The season was full of grueling bus trips as far as Winnipeg. Job security continues to be non-existent.

But the 2018 Texas Air Hogs are different, in many ways operating more similarly to a major-league club than to their American Association counterparts. The AirHogs fly on jets to most of their away games. The Chinese players live together at a local Country Inn & Suites, and are chauffeured to games, practices, and the area’s outlet malls, where they load-up on designer clothes and apparel that’s far more expensive back home. The players enjoy the services of a newly hired strength-and-conditioning coach (in the past, AirHogs players had to work out on their own), and they can take advantage of an in-stadium weight room that was built before the start of the 2018 season. These amenities were part of the pitch to the Chinese, and it showed that the AirHogs’ current management was more capable than the team’s past record suggested. “We’re not some fly-by-night independent group,” Onyett told me. The Chinese were, in fact, already well acquainted with this fact.

Before the 2017 season, the AirHogs were purchased by Neltex Sports, a North Texas group led by Donnie Nelson, the Dallas Mavericks’ general manager and president of basketball operations. Nelson—whose father, Don, is the all-time winningest coach in NBA history—has been a pioneer in importing foreign talent throughout his career, and he has been particularly active in China. Nelson participated in early basketball scouting trips to the country in the early nineties, pushed the Mavericks to draft Wang Zhizhi—who became the first Chinese player to make the NBA—in 1999, and currently serves as the chief advisor to the Chinese National Basketball Team.

During Nelson’s time in China, he’d become friendly with Sharon Qin, the CEO of Shougang Sports, a subsidiary of a Chinese state-backed steel conglomerate called Shougang Group. Shougang’s sports division works closely with the Chinese government (Qin was recently named vice executive director of the Chinese Olympic committee), and after Nelson purchased the AirHogs, he and Qin started talking about China’s baseball goals. Qin told Nelson that China wanted to get better. Nelson suggested the Chinese players—many of whom grew up playing other sports and came to baseball as teenagers—needed more games, better competition, and a more rigorous talent development system. The AirHogs’ could offer all of these things, and this past February, Nelson traveled to Beijing to finalize the deal. The team’s mixed identity is now reflected in its name. For the 2018 season, the AirHogs are known as the “Texas AirHogs powered by Beijing Shougang Eagles. “

Nelson isn’t the only member of America’s sports royalty involved in the 2018 AirHogs. Walk through the second floor of AirHogs stadium, and you’ll find a luxury suite designated for AirHogs’ co-owner and Hall of Fame catcher Iván “Pudge” Rodríguez. Enter the team’s front office a few yards away and you’ll find Billy Martin Jr, the team’s president of baseball operations, who has worked as a player agent for much of his career and prominently wears a 1976 New York Yankees World Series runner-up ring that his father, the Yankees’ legend Billy Martin Sr, received as the team’s manager. For the 2018 season, the AirHogs have been led on the field by the Chinese national team’s manager, John McLaren, a big-league-coaching veteran who had two stints as a major-league manager and was second-in-command of the star-laden mid-1990s Seattle Mariners teams of Ken Griffey Jr., Alex Rodriguez, and Randy Johnson.

The AirHogs’ leadership may have been experienced, but none of them were sure how the Chinese players would compete against the American Association competition—or if they could at all. Martin said that he had “heard all sorts of theories on how good or bad these guys were and none of them were quite right.” McLaren, a Houston native, had known some of the Chinese players since he took over the national team in 2011, and he admitted that before the start of the AirHogs 2018 season he “didn’t think we were ready for this.”

The team’s ten non-Chinese players had their doubts too. At the start of the season, the Chinese players struggled mightily on the field, and the clubhouse felt divided. Stewart Ijames—a 29-year-old former Arizona Diamondbacks minor-leaguer—told me that the first weeks of the season felt “like a middle-school homecoming dance.” The Chinese players were in their clique, and the vastly outnumbered mix of American and Latin American minor- and major-league veterans were off in theirs.

Communication was a constant struggle, but, gradually, the culture shock wore off. Ijames earned the name “big brother” from the Chinese players. He liked to offer up advice. He also liked to encourage his Chinese teammates to eat more so they could bulk up, piling fried chicken, buttery mashed potatoes, and the occasional protein shake in front of them. “They’re all a bunch of skinny guys,” Ijames said. “First thing I said was, ‘we gotta get some calories in these boys.’”

Ijames had taken a particularly shine to 24-year-old Li Ning. Li was a competitor, Ijames said, even if his scrawny physique made him look more like a team intern than the AirHogs’ starting catcher. And Li was eager to bridge the clubhouse divide, hanging out with the non-Chinese players on the road and becoming a devotee of Ijames’s favorite video game, Rory McIlroy PGA Tour.

Li spoke more English than most of the other Chinese players, which still wasn’t very much. When he and I talked, it was through Liu Xingping, an Indiana University graduate student who served as one of the team’s informal Chinese interpreters, and Li’s answers were rarely more expansive than a single word. As with all the AirHogs’ Chinese players, he’d had to adjust quickly to playing a full-season in America. The opponents were bigger and stronger. Pitchers were more prone to throw above 90 mph and challenge hitters with their fastballs. In China, Li had played just twenty games per season. Now, he was experiencing something close to the daily grind, even if he only started in half of the team’s games, sharing his position with another catcher, Luan Chenchen, whom the non-Chinese players referred to as “Baby Ruth”.

The AirHogs started the season abysmally. At the beginning of June, their record was 2-14. But signs began to emerge that there were better times ahead. Scott Sonju, who runs the day-to-day operations of Neltex Sports, told me that he knew things were looking up when an opposing pitcher beaned an American AirHog and the Chinese players responded by flooding out of the dugout and onto the field to come to his defense. The season had been punctuated by other small highlights that felt like major milestones. Perhaps the greatest had come on June 30, when Luo Jinjin, one of the team’s infielders, had seemingly out of nowhere put a perfect swing on a ball, lofting it into AirHogs Stadium’s left-field stands. It was the first and only time in the season that a Chinese player hit a home run. As Luo rounded second base, he raised his fist in the air, celebrating like he’d just hit a World Series–winning blast.

As Green and Norton and around 150 other fans awaited the first pitch of the AirHogs’ August 2 game against the Sioux City Explorers, the team’s broadcaster Joey Zanaboni was already hard at work, monitoring the chat box on the team’s streaming video feed and glancing up as an image of a waving five-star red flag appeared on the stadium’s giant screen. The P.A. system erupted with the triumphant blare of the Chinese national anthem.

“The March of the Volunteers,” Zanaboni whispered, savoring the melody. “When we go to Winnipeg they play three national anthems—that’s pretty cool.”

Twilight was setting in, and Zanaboni was moved to verse as the players took the field. “Come in under the shadow of this red rock, and I will show you something different from either,” he began. Finishing the stanza, Zanaboni looked to his right for a nod of recognition. None came. “T.S. Eliot,” he explained. “I’m a recovering English major.”

Soon Zanaboni was in a more colloquial mode, droning into his microphone in a joyfully put-on old-timey radio squawk. “Let’s kick these tires, let’s light these fires,” he said as the former Colorado Rockies pitcher Tyler Matzek threw his final warmup pitches for the AirHogs.

The night’s roster was typical. The starting lineup featured four American players and five Chinese players. The results were typical too. The Americans accounted for four of the team’s six hits and both of its RBIs. The AirHogs lost 6-2, but beating the Sioux City Explorers wasn’t really the point. The team’s thirty Chinese players would be leaving two days later for the Asian Games in Indonesia, where they have so far crushed Thailand and Pakistan and lost to Japan by a score of 17-2 . (Twenty other players from the national team arrived in Grand Prairie to replace them over the season’s final weeks.) After the Asian Games, there would be a likely return to Grand Prairie in 2019, the summer Olympics in 2020, and bigger hopes for the more distant future. “They’re really looking to the 2024 Olympics,” Sonju told me. “They understand that the development process is going to take a while.”

A few luxury suites down from Zanaboni’s booth, one of the men charged with the long-term development of the team was quietly observing the game. His name was Ma Zhenxin, although everyone around the AirHogs referred to him simply as Mr. Ma. I’d been told that Mr. Ma owned several stadiums in China, and he described himself, through Liu, the interpreter, simply as a “team leader.” Mr. Ma saw Chinese baseball on the brink of a golden period. When I asked him when the first player from Mainland China would make the major leagues, he mentioned that sixteen-year-old Jolon Lun, a right-hander with a reported 95 mph fastball, was already in the Milwaukee Brewers system.

The Chinese had been reticent to make too much noise about their season in Grand Prairie. But, Mr. Ma assured me, he saw a day when Chinese baseball would be ready for a close-up, and he thought the majors would be wise to seize on the country’s growing dedication to the sport sooner rather than later.

“There’s big potential if the major leagues signs a Chinese player,” Mr. Ma said. The marketing opportunities in China would be reason enough alone. And if that player became an international star, he would inspire a generation of Chinese children to take up the game. If everything went right, he might be to baseball what the Houston Rockets’ star Yao Ming was to basketball—a global ambassador and a nearly unrivaled popularizer, a figure who could bring his sport to millions of new fans. And while such a transcendent player was almost certainly not on the field that night in Texas, perhaps, with a little luck and a lot of work, he would be soon.

- More About:

- Sports