In the early 1990s, Robert Rodriguez may have been the most exciting filmmaker in the world. He made his name in the burgeoning indie film scene quickly, as perhaps the most unlikely of his class of auteurs. Spike Lee and Quentin Tarantino had the most critical acclaim and Kevin Smith and Richard Linklater had the most personal approaches to storytelling, but Rodriguez had the madcap sense of experimentation that made indie film seem like a movement with no limit. Smith charged $20,000 on credit cards to make Clerks and hardly ever moved the camera from its perch in a New Jersey convenience store. Rodriguez had less than half of that for El Mariachi, and made an action movie full of shootouts and jailbreaks. The particular talents Rodriguez displayed—a sense of adventure, grand ambitions, an ability to make a dollar out of fifteen cents—made Hollywood froth at the mouth and ask a promising question: What would this guy do with a real budget?

Initially, the answers were exciting. In 1995, he followed Mariachi with a pseudo-sequel, Desperado, that cost $7 million and grossed nearly four times that; the next year, he quickly turned around a Tarantino script for From Dusk Till Dawn, another profitable film (and the one that launched George Clooney into movie stardom). Rodriguez had an easy system: he kept costs low, maintained creative control of his projects, invested in technology, and turned a profit. In the late 1990s, he turned down the opportunity to helm the X-Men franchise and instead decided to create his own adventure series, Spy Kids, scoring his biggest hit yet.

Spy Kids was the start of a new era for Rodriguez. The 2001 family film, about the children of two James Bond-like super spies (played by Antonio Banderas and Carla Gugino) who have to rescue their parents, cost $35 million, which was nearly double most of his earlier budgets. It also went on to gross more than $110 million, earning both his biggest box office figure and his best critical reviews. A year later, he released a sequel, Spy Kids 2: The Island of Lost Dreams, but he really lived up to his reputation as an innovator with the next film in the series.

Released in 2003, Spy Kids 3D was years ahead of the 3D boom. Rodriguez had always been a tech-focused filmmaker, and the third Spy Kids installment was the first non-documentary film to be shot with James Cameron’s Reality Camera System. It was the sort of pioneering move that met his early promise as an unconventional, adventurous filmmaker.

His interest in technology also helped him keep costs down. Desperado had been a huge hit on DVD, and the studio pushed him to make a sequel. Rodriguez was skeptical that he could shoot the kind of epic he envisioned in Mexico at the time, until George Lucas introduced him to the newest wave of digital cameras. Armed with the technology, Rodriguez became the first filmmaker to use high-definition digital video for a big-budget feature, and he shot Once Upon a Time in Mexico in seven weeks, a lightning turnaround time for a big-budget action movie.

Throughout the mid-aughts, his string of hits continued. Once Upon a Time in Mexico turned a profit; Sin City grossed $74 million on a budget half that size, and spawned a franchise. He didn’t make a film that lost money at the domestic box office until The Adventures of Shark-Boy and Lava Girl 3D, his worst-reviewed film and a box office flop.

Prior to Shark-Boy and Lava Girl, his movies all enjoyed a baseline level of both critical respectability and profitability. After the family film, his fortunes dwindled. He teamed with Tarantino for a theatrically-released double feature called Grindhouse, a commercial flop that eschewed innovation in favor of serving as a pulpy throwback. A 2009 family film, Shorts, barely earned back its budget and received poor reviews. Rodriguez returned to the “grindhouse” style of throwback filmmaking for Machete, a 1970s exploitation-style vehicle for Danny Trejo, which made money on a low budget. He attempted to reboot the Spy Kids franchise in 2011 with Spy Kids 4: All the Time in the World, which was a critical bomb and a box office disappointment. He made a second Machete movie in 2013, and it became his first film to lose money, grossing a dismal $8 million domestically on a $20 million budget. (Demonstrating Rodriguez’s knack for cultivating talent, it was the cinematic debut of Lady Gaga.) A second Sin City the following year similarly bombed, and Rodriguez stepped away from feature filmmaking in 2014 to focus on running his television network, the struggling El Rey.

As a cultural force and a relevant filmmaker, it would be fair to say that Rodriguez peaked around 2005, before taking a precipitous professional decline over the past five years.

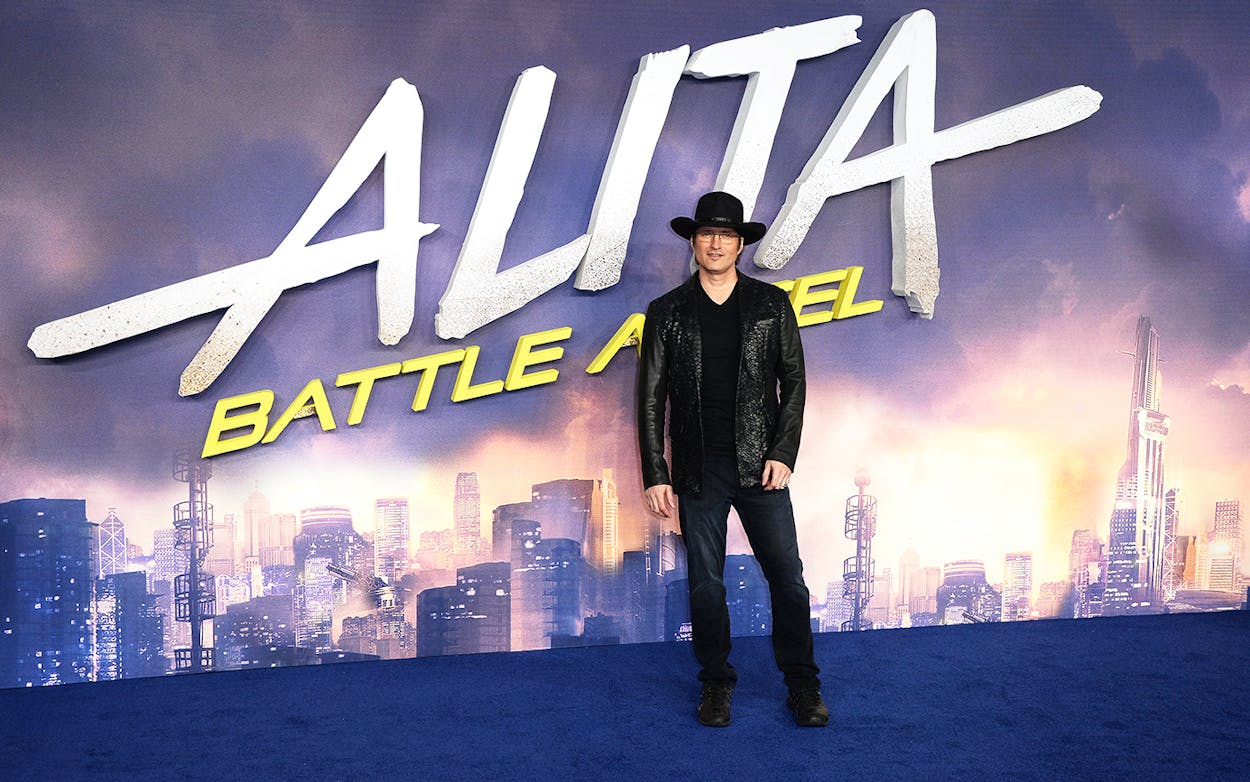

A funny thing happened in late 2016, though. Despite a string of largely unsuccessful productions, Rodriguez found himself tapped by James Cameron—the director of two of the five highest-grossing films of all time—to helm Cameron’s dream project.

Cameron had been working since 2003 to adapt the Japanese manga title Battle Angel Alita as a live-action feature, but the famously slow-moving director had other projects that continued to get in the way. He shot a documentary, Ghosts of the Abyss, in 2003, and Avatar in 2009. He developed new filmmaking technology, explored the oceans, and committed to making three sequels to Avatar. Unable to make Alita on his own, he recruited Rodriguez.

Alita represents Rodriguez’s largest budget to date. According to The Wrap, the film cost $200 million to make—four times the budget of any previous project in Rodriguez’s filmography—and took five months to shoot. The post-production process lasted two years.

All of this is a major change in how Rodriguez works, and it’s also the fulfillment of the question people have been asking since El Mariachi: What does it look like when you give Robert Rodriguez the same budget you give a Marvel or Star Wars movie and send him out to tell a story?

The result, in Alita’s case, is mostly good. Rodriguez has never struggled to attract talent, and the cast of Alita is excellent. The film stars A-list talent like Christoph Waltz, Jennifer Connelly, and Mahershala Ali alongside Rosa Salazar, who’s previously done her best work in television and indie rom-coms (including the tragically overlooked SXSW hit Night Owls), in the title role. Alita opens with avuncular bounty hunter Dr. Ido (played by Waltz) scavenging for parts in a junkyard on the outskirts of the futuristic megalopolis of Iron City. He finds the remains of a cyborg and rebuilds her body, dubbing her “Alita” when she awakens a blank slate. Alita learns of the underbelly of the world she’s woken up in and decides to take a side in its civil strife, meeting its morally ambiguous characters in the process: Chiren (Connelly), a wealthy engineer with dreams of a better life; Vektor (Ali), the menacing agent of an unseen oligarch that rules over Iron City; and Hugo (newcomer Keean Johnson), a young scavenger who plays a futuristic sport called “Motorball.”

Having such a stellar cast helps, especially in Alita’s first act, which features clunky dialogue and huge, awkward dumps of exposition. Alita starts the film as a wide-eyed naif, a sort-of manic pixie dream cyborg without much personality, but she comes into her own when the film takes its action-adventure bent. Throughout the film, Salazar plays Alita as a hormone-driven teen, full of intense feelings for the first boy who pays attention to her, a righteous sense of justice that’s inspiring in part because of how laughable the other characters find it, and an eagerness to see what her newly-rebuilt cyborg body can do. Writing has never been Rodriguez’s primary talent, but the script edges its way from serviceable to charming as Alita progresses.

Even if the script is clunky at times, the visual flair of Alita never is. Rodriguez was an exciting young talent because of his vision as a filmmaker, and he creates a fleshed-out, lived-in world. His Iron City isn’t just the realm of half-machine bounty hunters and Motorball enthusiasts. There are cyborg musicians, playing impossible notes on guitars with their extra hands; rebuilt dogs who lay at the feet of empathetic cyber-masters; futuristic chocolate stands with signs in English and Spanish. There’s a strangeness to his world that serves it well, recalling the idiosyncrasies—the unnamed alien creatures that pop up in the foreground—that J.J. Abrams brought back to Star Wars in The Force Awakens. Alita has the sort of striking visual sensibility that Rodriguez demonstrated in his earlier work—he essentially reinvented film noir in Sin City—but has moved away from in the past decade.

More urgently for a sci-fi adventure, Rodriguez’s action sequences are among the finest of not just his career, but of any in a recent blockbuster. Often, blockbuster fight scenes are jumbled, even boring, affairs that replace choreography with quick editing and dim lighting (Black Panther is a monumental achievement, but try keeping track of T’Challa and Killmonger as they battle on the train tracks during the climax). Alita‘s battles soar, as clear staging and thrilling 3D visuals tell the story of the hero learning to use her powers.

Whether that’s enough for Alita to succeed is still an open question. It’s his best-reviewed movie in years, with a 61 percent “Fresh” rating on Rotten Tomatoes a few days ahead of its release. According to the box office tracking, though, it’ll likely take a minor miracle for Alita: Battle Angel to be considered anything other than a flop. Those kinds of miracles do happen—Deadpool, released the same weekend in 2016, famously grossed more than twice what experts projected—and when they do, it’s usually because of strong word-of-mouth. Fox, interested in building that kind of buzz, held free nationwide screenings of Alita two weeks before its release.

If Alita is the film that makes Rodriguez once again the toast of Hollywood, he’ll probably do something interesting with the opportunities it brings. If not, he seems prepared to weather that outcome, too. Less than a month after the release of Alita, Rodriguez has a second 2019 feature premiering at SXSW. This one, Red 11, was shot for the same $7,000 budget he had for El Mariachi. That ultimately speaks to his greatest strength as a filmmaker, one even more pivotal than his visual sensibility: his ability to find a way to make a movie on his terms, no matter what anyone else thinks.

- More About:

- Film & TV

- SXSW

- Robert Rodriguez

- Austin