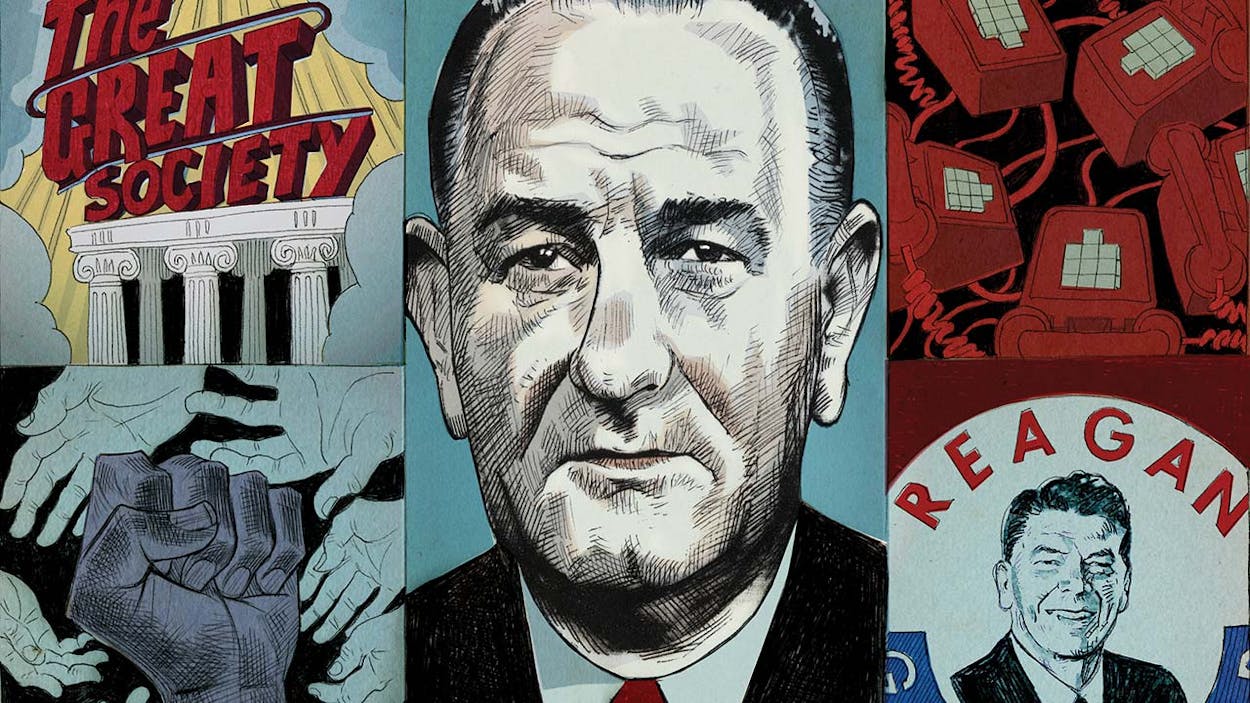

Almost from the moment Lyndon Baines Johnson announced he would not seek reelection in 1968, he became the president America wanted to forget. And for almost half a century we did a pretty good job of it, largely limiting consideration of LBJ’s legacy—when we thought of it at all—to the war we also wanted to forget, Vietnam. But despite relying so heavily on its short-term memory, our culture is also strangely addicted to revivals, and LBJ is having another moment in our national consciousness. While the first two volumes of Robert Caro’s shelf-straining biography convinced most readers that LBJ deserved his dark corner in the nation’s attic, the most recent, The Passage of Power (2012), inspired nostalgia for a hands-on, relentlessly jawboning legislative tactician who seemed to be everything a diffident, hands-off President Barack Obama isn’t. LBJ hadn’t been the subject of a hit play since the scathing 1967 MacBird! (which implied he was responsible for JFK’s murder), but last year’s Tony Award–winning drama All the Way, timed to the fiftieth anniversary of the landmark Civil Rights Act, recast him as a flawed but sincere champion of racial justice. The Oscar-nominated Selma, which portrayed him as a much more reluctant convert to the cause, actually suffered a pro-LBJ backlash that reportedly hurt its chances of winning. Savaged and then cast out by the popular culture of his time, LBJ is finding redemption in ours.

This year we’re celebrating the fiftieth anniversary of a litany of legislative achievements that followed Johnson’s historic 1964 landslide victory over Barry Goldwater, ranging from the Voting Rights Act to Medicare and Medicaid—an epochal expansion of government that remains at the center of our national political dialogue long after LBJ himself became he-who-must-not-be-mentioned. Several new books by historians, journalists, and scholars—along with a reissue by a key adviser—are putting LBJ back into that conversation, and they all address a question that remains highly relevant to our future: Now that we are no longer determined to forget LBJ, how will we remember him? Was he the lying, power-mad opportunist who built a vast welfare state intended to sap our freedoms, destroy our businesses, and turn us into a nation of “takers”? Or was LBJ one of those pivotal presidents, like Lincoln and FDR, who stepped forward in a time of existential crisis and rescued us from the darkest angels of our nature?

Brooklyn-born, Harvard-educated Joseph A. Califano Jr. was working for Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara when he was essentially press-ganged onto LBJ’s White House staff in the summer of 1965, as the president’s chief domestic policy ramrod. Califano’s sometimes riotous workplace memoir, the recently reissued The Triumph and Tragedy of Lyndon Johnson: The White House Years (Touchstone Books), was lauded when first published, in 1991, and the subsequent release later in the decade of LBJ’s secretly recorded Dictaphone tapes only confirmed Califano’s pitch-perfect rendition of what would have been one of the most distinctive characters in American fiction had he been the author’s invention.

In a classic set piece, Califano hasn’t even been formally hired when he’s dispatched to the LBJ Ranch for a weekend that more resembles a fraternity hazing than a policy powwow with the leader of the free world. LBJ continually refreshes himself with Cutty Sark and soda while he takes Califano on a hot, dusty two-day tour of his Hill Country properties by car, boat, water ski, helicopter, and an amphibious vehicle that Johnson deliberately drives into a lake, evidently for the sheer pleasure of further discomfiting his already shell-shocked guest. Midway through the tour, LBJ invites Califano to examine a spontaneously bared presidential buttock for a suspected—and hastily confirmed—boil.

Back at LBJ’s White House, there’s something of a Sun King vibe. Top aides trail the naked president into the bathroom, taking orders while he showers, shaves, and brushes his teeth. He eats and power-naps whenever he pleases, changing into fresh jammies for the latter. Decades before the Internet, LBJ can instantly reach out to staffers with a network of shrill red phones labeled “POTUS”; these presidential hotlines are so ubiquitous that Califano is instructed to install one in his office bathroom.

In the end, however, LBJ’s control-freak approach to the minutiae of his office—down to how much hairspray his secretaries should use—resulted in really big accomplishments. In “We Are Living in Lyndon Johnson’s America,” a new introductory essay written for the reissue of The Triumph and Tragedy, Califano proudly lets sheer numbers make the case for his former boss’s greatness: more than a hundred million Americans now receive their health care under Medicare and Medicaid; forty million benefit from LBJ’s food stamps; ten million needy schoolchildren start the day with LBJ’s school breakfast program. These beneficiaries may be vilified as takers in today’s conservative rhetoric, but Mitt Romney can testify to the difficulty of removing the “47 percent” from a political calculus that was long ago determined by LBJ.

Godfrey Hodgson covered both the Kennedy and Johnson administrations for the London Observer, and the title of his new book, JFK and LBJ: The Last Two Great Presidents (Yale University Press), eliminates any suspense regarding his estimate of LBJ’s stature. With his largely illusory youthful vigor, JFK provided the tone and vision for a new America. However, history required that LBJ, nine years older but willing to risk literally working himself to death, do the heavy lifting necessary to transform JFK’s vaporous New Frontier into the realities of day-to-day governance—and then expand it into his own vision, the Great Society.

Hodgson’s outsider perspective makes him an unusually perceptive observer of America, and of Texas in particular. He cites LBJ’s roots in the historically populist, liberal-minded Hill Country rather than simply labeling him a generic Texan with an inbred conservatism—an oversight that Hodgson believes has led many, Caro included, to mischaracterize LBJ’s zigging and zagging between the liberal New Dealers and the racist Dixiecrats as nothing more than amoral opportunism. Hodgson’s LBJ, his views shaped by a rapidly modernizing Texas that “was not really either old-fashioned or backward or provincial, as the New Yorkers imagined,” is represented as a true believer in shared prosperity and racial justice. “Many suspected him when he came to the White House of being conservative, racist, even corrupt. He proved that he was none of those things,” Hodgson writes. Instead, LBJ was “magnificently brave, confident, and, if tactically crafty and well used to equivocation, he was also, like Bunyan’s pilgrim, valiant for truth.”

Princeton University history professor Julian E. Zelizer takes a different tack in The Fierce Urgency of Now: Lyndon Johnson, Congress, and the Battle for the Great Society (Penguin Press). No less impressed with the enduring edifice of the Great Society than Califano and Hodgson, Zelizer nevertheless finds its traditional origin narrative too “Johnson-centric.” While hardly denying LBJ’s exceptional political gifts, Zelizer insists that LBJ’s agenda would have remained deadlocked, like JFK’s, in a Congress long held hostage by a coalition of deeply conservative Southern Democrats and Midwestern Republicans, if not for the extraordinary moment provided by the civil rights movement. Thanks to the widely televised moral suasion of nonviolent protesters and the brutal intransigence of their segregationist opponents, which sharply shifted public opinion, conservative legislators were sufficiently back on their heels that LBJ could muscle through the 1964 Civil Rights Act.

That blow to the conservative coalition was followed up by an even more devastating wallop, the “extremism in the defense of liberty is no vice” candidacy of Barry Goldwater. The Arizona senator so terrified a nation living under the threat of a nuclear holocaust that Johnson not only won the highest share of the popular vote—61 percent—in presidential history but carried in on his coattails a new Congress with a dramatically culled and cowed conservative coalition. (One of Zelizer’s chapters is titled, with only slight irony, “How Barry Goldwater Built the Great Society.”) But even then Johnson told civil rights leaders that he wanted to pass the education and health care components of his Great Society before turning to the Voting Rights Act, until his hand was forced by the violent reception of civil rights marchers in Selma, Alabama, in March 1965. (It’s this tactical hesitation that Selma misrepresents, for purely dramatic purpose, as LBJ’s strategic opposition to voting rights.)

However, LBJ applies the decisive political leverage so often in Zelizer’s narrative that the author’s historical revisionism ends up more convincing as a call for present-day activism: “A grassroots movement and sea change election were critical to the liberal ascendency that overwhelmed, if briefly, the forces of conservatism that had been, and are today, so strong.” That’s Zelizer’s most compelling insight: if after half a century LBJ’s Great Society remains substantially intact, the even hoarier Southern-Midwestern conservative coalition that has always opposed it is also little changed, except that its Southerners are now all Republicans.

In Landslide: LBJ and Ronald Reagan at the Dawn of a New America (Random House), Newsweek writer Jonathan Darman sets up a side-by-side comparison of his two protagonists with a fascinating novelistic conceit: employing a straight time-line narrative, Darman chronicles their parallel lives from the day of JFK’s assassination to the 1966 midterm election that sharply reversed the Goldwater windfall of congressional Democrats—the same election in which has-been actor and first-time office-seeker Reagan improbably defeated California’s popular incumbent governor and began his march to the White House. “In the course of the thousand days,” Darman writes, “Johnson and Reagan each captured the nation’s attention by confidently offering a story of America and the path it needed to follow.”

Some intrepid producer should buy Landslide’s screen rights just for Darman’s account of Reagan’s far-from-steady progress from the set of The Killers, where on November 22, 1963, the former B-movie leading man was stuck in a seamy, unflattering character part (lead actress Angie Dickinson, rumored to be a special friend of JFK’s, collapsed when they got the news), to his unexpected role as a governor-elect who was already getting feelers for a presidential campaign.

But Darman just as vividly dramatizes LBJ’s thousand days, frequently with illuminating flashbacks (cut to thirties-era Johnson, newly elected to Congress, instructing his aide to always refer to him by his initials in press releases: “FDR-LBJ—do you get it?”); from time to time the narrative even crosses over into actual screenplay format. Fueled by a high-test psychological mix of insecurities and ego, knowing with every political bone in his body that his electoral mandate is ephemeral, LBJ pushes forward his Great Society in a state of unremitting anxiety, waiting for the inevitable white, suburban backlash that will send his most valuable political asset, a liberal-dominated Congress, out to pasture. Equally attuned to that backlash, Reagan astutely waged his 1966 gubernatorial campaign against LBJ rather than incumbent Pat Brown.

Darman, however, doesn’t cast either Reagan or LBJ as the hero in this engrossing docudrama. “By the end of the thousand days . . . the tradition of realism and humility in mainstream politics was gone,” he writes of two men who understood all too keenly that the effectiveness of their political storytelling depended on their own carefully crafted, larger-than-life images. “In its place was a new kind of politics in which voters chose between two fantasies of the American future, two myths in which the federal government could only be America’s salvation or America’s ruin. . . . Today their lingering myths make the country hard to govern at all.”

Yet given today’s endemic antigovernment sentiment and LBJ’s near-invisibility for most of the Fox News era, it’s remarkable that his story still has legs. LBJ’s Neglected Legacy: How Lyndon Johnson Reshaped Domestic Policy and Government (University of Texas Press), a collection of scholarly essays intended as a sort of half-century report card on LBJ’s policies, offers considerable insight into how the Great Society has endured despite fundamentally changed public expectations of—and confidence in—the federal government. LBJ took a broad, holistic approach to civil rights that included economic development, mass transit, and federal aid to schoolchildren, greatly increasing the complexity of his Great Society but also vastly strengthening its foundation. Having entered government as a congressional staffer and then New Deal administrator, LBJ wasn’t just the arm-twister-in-chief but also a master architect of the bureaucratic, regulatory, and enforcement apparatus that made his rhetoric work in the real world. Contemporary America is a more just and equitable society, in substantial part because LBJ gave the federal government the tools—and sharp teeth—to make it so.

However, as LBJ’s Neglected Legacy points out, the sleeper policy that may well ensure the persistence of the Great Society far into this century—and perhaps allow LBJ to ride into history wearing a white hat—is the 1965 Immigration Reform Act, a Kennedy brothers initiative designed to lift restrictions on non-European immigrants. Neither the Kennedys nor LBJ could have foreseen the flood of Latinos and Asians that has forever altered America’s demographic profile. But the extent of minority participation in future elections, the clear target of repeated conservative attacks on LBJ’s Voting Rights Act, will determine whether the Great Society survives. If Reagan’s principal legacy was an inflexible antigovernment theology that has assured his near-divinity among its adherents, LBJ bequeathed us something more tangible but also more fluid in its possibilities: an increasingly diverse nation that may yet discover his greatness.

- More About:

- Texas History

- Politics & Policy

- Books

- LBJ

- JFK