The changing of the season brings with it new colors and new styles—French Vogue tells us that Bubblegum Pink will be the hot new color this winter. There is a changing of styles in politics, too—the hot new white supremacist this winter is a man named Richard Spencer, a product of Dallas.

Spencer has emerged as one of the biggest beneficiaries of this year’s election. Nearly no one had heard of his movement, the self-identified “alt-right,” at the start of the year, but the movement rode the coattails of Donald Trump’s presidential campaign to prominence, kicking off an endless stream of profiles of Spencer and stories about his friends. Spencer isn’t exactly a neo-Nazi, but it’s hard to say quite what he is. His end goal is the forceful transformation of the United States as it currently is, and the creation of an ethno-state within for the furtherance of the white race. He calls white people the “children of the sun,” and a speech he gave last month ended in his audience giving the Nazi salute to an exhortation to “hail Trump.”

Is all the attention directed toward Spencer appropriate? Whatever the answer, he’s the man of the moment. Texas A&M alum Preston Wiginton, who has his own history at the university, invited Spencer to speak at the university’s student center on December 6, a speech the school said it was unable to prevent. (People are allowed to reserve areas of A&M’s campus for private events.) Spencer spoke to a crowd of critics and admirers at Texas A&M, an event that had Aggies struggling with many of the same questions Americans have been confronting over the last month—why do we believe what we believe? And how should we act in defense of those beliefs?

College Station seems an unlikely corner of the country for this national crisis of conscience to play out, but there it did. At A&M’s Kyle Field, school officials attempted to drown out Spencer with an exceptionally earnest pep rally for American pluralism and Aggie values. In the adjacent Memorial Student Center, where Spencer’s speech was held, A&M students engaged his movement face-to-face—to embrace, heckle, or debate him. And between the two buildings, a large crowd of protesters, many from out of town, came to oppose Spencer with signs and chants, physically squaring off with a cordon of state police in riot gear.

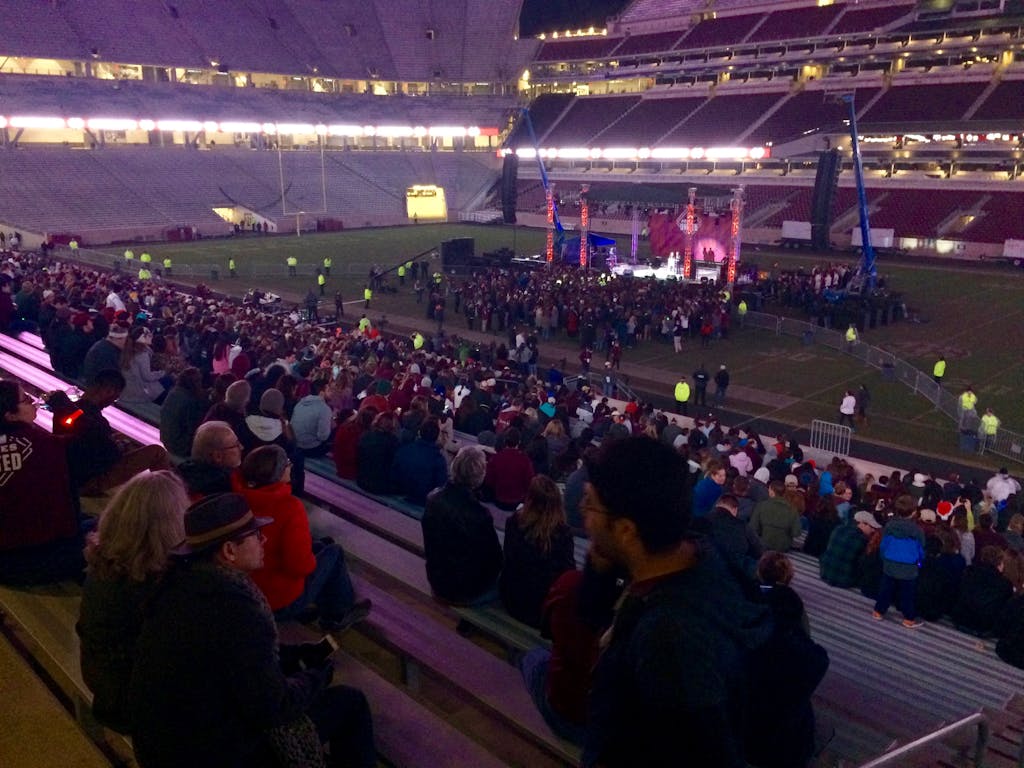

The Kyle rally—officially termed “Aggies United”—was the largest event of the three, attracting a crowd of several thousand, huddled in the cold on the field and northeast bleachers of the stadium. The initiative of Texas A&M’s leadership, the event was a hastily assembled bells-and-whistles attempt at counter-programming Spencer’s speech.

The lineup was filled with friendly faces to represent the school — a huge number of athletes, entertainers, administration officials, and a Holocaust survivor named Max Glauben. What Spencer offered, they told the audience, was an affront to Aggieness, a universal creed, and it would not be tolerated. “Tonight we celebrate the triumph of human spirit over hateful spirits,” said one emcee. “Aggies are united!” He led the audience in a chant. Stage left: “Aggies!” Stage right: “United!”

As a school with a focus on the hard sciences, A&M is a melting pot all its own, with a huge number of foreign students. And its military focus fosters another kind of universalism, as John Sharp, the chancellor of the A&M system, reminded the crowd when he took the stage. “As a fish in the Corps of Cadets, the first thing I had to memorize was the inscription engraved on the top of the door at the north entrance of the Memorial Student Center,” he said. “That inscription says ‘Greater love hath no man than this: that a man lay down his life for his friend.’”

Sharp went on to tell the story of his father, who stormed the beaches at Leyte Gulf in World War II. “A mortar blew up behind him and incapacitated his legs,” Sharp said, describing how his father laid there preparing to die until a fellow soldier ran from cover to drag him to safety. Sharp’s father only knew one thing about the man—“He was cussing all the way in Spanish.” Here was one bond that transcended race: “He was an American soldier.”

Sharp offered another. “For the last 48 years, people have done things for me that didn’t know anything about me. But we had one thing in common: We had this ring. There are 450,000 of us out there that love you and that don’t even know you,” he said. “There is no university where love and respect and commitment for each other is stronger than Texas A&M.” Sharp left the stage and was replaced by Yell Leaders, who led the crowd in another chant.

The event also took special care to reassure nonwhite Aggies that the university supports a message of unified community. “Tonight, nobody’s prayer for a friend, for support, for inclusion goes unanswered,” said Dr. Michael Young, the president of A&M’s flagship campus. But it was also, self-consciously, an attempt to preempt the terrible P.R. produced by Spencer’s visit. “We’re not gonna let anybody define what Texas A&M is,” Young said, hopefully. “We decide what Texas A&M is.”

But, at the end of a year drenched with bile, the counter-protest presented as an earnest mash note to the kind of big-hearted American pluralism that seems momentarily, at least, on its back foot. “We’re all so beautifully different,” Young said. “Our cultures, our shapes, our sizes, our ethnicities, our backgrounds. But our differences enrich us. Our differences make us complete. I know of no God who sees in races. And that’s wonderful.”

The peppy emcee piled on to this idea when he retook the stage. “I flew in early enough to hang out with Reveille,” the Collie that serves as A&M’s mascot, he said to cheers. “Reveille said, Aggies United is about us all coming together!” More cheers. “Reveille also said, remind them that Love Trumps Hate!”

Outside of Kyle Field on the street dividing the stadium and the student center, a very different gathering was taking place. A crowd facing the student center entrance—an entryway topped with the word “respect,” through which attendees had to pass—brought signs and chants to bear on the enemy, their words echoing off the tall flat walls of Kyle Field.

It was a peculiar confluence of people, featuring a great many A&M students and a great many members of the activist left, with the seams between the two often very visible. On one hand, protestors came from Austin or Houston to make their presence known, many toting signs bearing the traditional left messages—“¡No pasarán!” from the Spanish Civil War, “Nazi Punks Fuck Off,” from the Dead Kennedys, “Bash the Fash,” and on and on.

The left-wingers came for confrontation, and they found outlets for it. A handful of far-right guys materialized in a corner at some point during the night, with one guy holding a homemade Trump-Pence sign and one particularly confused fellow whose effort read “If Diversity Is So Great, Why Is It Only For White Countries?” A man with a megaphone, a member of the Bash the Fash crowd, found the far-right guys. “You came here to protest Neo-Nazis, right?” he asked the crowd. “Well, come over here and f—ing fight them.” A chant started: “Follow your leader and kill yourself.” A follower of cult leader Bob Avakian’s Revolutionary Communist Party squared off against a squat white nationalist with a long rat-tail, each filming the other, cameras inches from each other’s faces.

When state police with big plastic shields started to push protesters away from the school building, different chants started, like “cops and Klan go hand in hand.” It was a carnival, a clash of cultures as pronounced as anything else that night. Texas A&M ranked as the most conservative college campus in the country, according to Princeton Review in 2015, and many students watching the event seemed bewildered. “All I wanted was to go to Smoothie King,” said one student, unable to get past the crowd. Many others in maroon shirts hung back at the perimeter, watching and listening.

Abigail Wall, a business management major, stood huddled with her boyfriend on a low wall near the crowd. The whole thing was silly, she said. “This is just people chanting ignorant stuff,” she said. “You can’t drive out hate with hate.” An immaculately dressed professor with a British accent who declined to give his name dipped in and out of the crowd, grimacing. “I think this is an incredible overreaction. It’s exacerbated the situation. It’s made it worse than it needed to be,” he said. “I find it hard to believe that he couldn’t have been prevented from speaking here.”

But many students A&M were happy to see strong turnout, and not every out-of-towner was a punk. Audrey Patton, 84, came with a friend from Kurten, a little town outside College Station. They held signs that read “Heil No.”

“I think it’s important that [Spencer] see that he can’t just say that stuff and have it responded too. That we will speak if he speaks up,” said Patton, whose initiation into protest started with the Iraq War. “I was a little girl during World War II and I remember that didn’t turn out well for anybody,” she said wryly. “And Mr. Hitler, as you know, came to power legally. Never let people forget that.”

Inside the student center, Spencer gave a brief press conference, spoke for only a half-hour, and took questions for an hour more. Spencer is a peculiar figure. His novelty exists largely because he looks and acts a little more “respectable” than most of his fellow travelers, but at times he too seems oddly cartoonish. His publicity photo, which he prefers to use, features his strong-featured face and his “fashy” haircut, shaved on the sides and swept over on the top. The background is snow, and he looks both steely and goofy at the same time, like Macklemore if he had joined the Waffen-SS.

There’s been a lot of debate about whether the media is using strong enough terms to describe Spencer and the alt-right. But negative coverage of Spencer, and denunciations from the center are just as useful to him as any other kind of attention.

“I almost want to thank President Young for having this rally across the street,” Spencer said. “Because the fact that they want to fill a football stadium for the world’s largest safe space shows how much power the alt-right and our ideas have. He may think that he’s drowning us out, but he’s actually making us much more powerful by directing energy to us.”

Even broadly negative stories build Spencer up in stature—he’s often described as an “architect” of the alt-right, a new leader of the white power movement, uncommonly charismatic or persuasive, someone to fear. The power of Spencer’s ideology comes precisely from the fact that it is taboo, that it is denounced by the mainstream—disaffected young white men are drawn to his banner for precisely the same reasons others come to love ISIS. But watch him for any amount of time, and the truth emerges, one more damning than any hit piece could deliver: He’s a generally mediocre public speaker, whose core concepts are not particularly strong or unique, and vulnerable to critical dissection.

At the speech last month that ended with the “Hail Trump” chants, Spencer read a long list of prepared sentences in an odd, arrhythmic voice while staring intently down at his notes, often slipping into meme-speak, Pepe and kek and “meme magic.” In College Station he did a little better, walking the stage with his sleeves rolled. Many members of the crowd were there to antagonize him. A woman in a clown costume repeatedly got up to dance in front of the stage, holding punny signs like “You’re a Pee’in.” There were repeated heckles, and the Q&A was often hostile.

Come at Spencer with ill-formed questions or weak jabs, and he’ll bat you down. That’s what he does well, and what his fans enjoy. He repeatedly called the clown woman fat, thereafter issuing a high-pitched, tittering laugh. He remained assiduously calm, delighted by anger or disgust from his opponents, like one woman who rose to call him an “asshole.”

But he’s not immune to criticism, and his core message is—it’s hard to put this any other way—weird. Early on in the Q&A, an African-American student rose to question him. “I firmly believe in freedom of speech, and I firmly believe that challenge is done in this room, not across the street,” he began. Producing a page of congressional testimony, he related that huge numbers of students pursuing advanced science and engineering degrees in the U.S. are foreign born—a majority, in some fields. Meanwhile, public education funding in America has been cut dramatically. And the nation’s food supply is dependent on “migrant farmers who are basically the only ones who can do the work.” (Spencer proposes a long-lasting immigration ban.) After listing all of this information, the questioner posited, “Would you actually have Americans that are stupid and starving all that time just to satisfy your ego?”

Spencer smiled, but it was one of the few times he seemed to show anger, the mask slipping. “I want white people picking sweet potatoes. We can goddamn well do it ourselves.” The question was “one of the stupidest things I’ve ever heard in my life,” Spencer said. And even if it did mean stupidity and hunger, “I would still prevent immigration, because this is our goddamn country.”

Spencer’s goal is to displace conservatism, which he calls “boring” and “nonsense,” with his brand of white identity politics. What’s at the core of that? Well, whiteness. What is great about whiteness? In fleshing this out, Spencer is at his slipperiest, and his argument weakest. Whiteness is amorphous, indefinable, the quality of the people who got on ships in funny explorer hats, who went to the moon, who settled lands. Spencer presents the existence of whiteness as a scientific fact, a reality others deny, but his version is a poetic ideal: Because the English got on many boats in one period, and the Germans built superior steam turbines in another, so, too, is the greatness they shared in the blood of the Irish and the Croats. That’s why the predominantly young men of the alt-right love Spencer—he endows them with greatness, purpose, and meaning that is theirs by default, even if their primary accomplishment in life is accruing Reddit Gold.

He’s a historian by training, but his heart is in philosophy—he credits his ideological turn in part to first reading Nietzsche in college. (There’s a long line of young people whose brains were melted by Nietzsche.) That’s what whiteness is—an intangible philosophical concept, like Virtue or Good. But history is the story of causes and consequences, not unnamable spirits. For all of Spencer’s vaunted firepower as an “intellectual,” his worldview is built around one big tautology and a long list of concepts he doesn’t, or can’t, flesh out.

None of this is to say that what Spencer represents is not worthy of concern. But Spencer, the man, is not good enough to be feared. Were he in almost any other field, he would be unlikely to stand out—his only power is provocation. The perplexing thing, ultimately, is how much we’ve helped him along.