Raymond Caldwell finished reading the play that would nearly ruin his life on an early August night in 1999. He reached the last line and sat back in his recliner, which overlooked the backyard garden of his Longview home. He held the script in his hands for a while. And then he put it aside.

Caldwell, who has pale blue eyes and a bald head ringed by snowy white hair—he may be the only East Texan ever described by the New York Times as “elegant”—was 56 years old at the time. He’d taught for more than two decades at Kilgore College, a two-year school best known for its high-kicking drill team, the Rangerettes. Caldwell chaired the theater department, and he produced student plays that came and went each semester with little fanfare: Our Town. The Glass Menagerie. A lot of lightweight comedies. This play was different. Angels in America: A Gay Fantasia on National Themes had won the Pulitzer Prize for Drama in 1993 and the Tony Award for Best Play in both 1993 and 1994. (At around seven and a half hours, it was so long that it was split into two parts.) A number of critics hailed the play, written by Tony Kushner, as the most significant theatrical work in a generation.

Caldwell was considering about a dozen other scripts for the fall semester production, but over the next three weeks, he couldn’t shake Angels from his mind. He read it three more times. No modern play had resonated with him on so many levels. “This is the kind of thing I should be doing,” he told himself.

But Caldwell hesitated. He knew that artistic merit carried only so much weight in Kilgore, a conservative Piney Woods oil town. Angels in America’s frank depiction of homosexuality and the AIDS epidemic of the eighties was guaranteed to inflame many of the churchgoing people who lived there.

At the time, the world was changing. President Bill Clinton had declared June 1999 the nation’s first “Gay and Lesbian Pride Month,” and TV sitcoms like Ellen and Will & Grace were bringing openly gay characters into millions of living rooms.

But change often incites backlash. In response, perhaps, to the AIDS crisis and the increasing visibility of gay people, an epidemic of antigay violence swept Texas in the late eighties and nineties, often to public indifference. “I don’t much care for queers cruising the streets picking up teenage boys,” Dallas state district judge Jack Hampton told the Dallas Times Herald in 1988, while discussing an unexpectedly light thirty-year sentence he’d given to a double murderer. The beneficiary of Hampton’s lenience had shot one of his victims three times on a hilltop clearing in Dallas’s Reverchon Park. He’d then turned his pistol on the other victim, planting a foot on the man’s leg to prevent him from crawling away. Then he finished him off. “I’ve got a teenage boy,” Hampton told the newspaper. “These homosexuals, by running around on weekends picking up teenage boys, they’re asking for trouble. They really are.”

In the final weeks before the fall semester began, Caldwell remained torn. He badly wanted to bring Angels in America to Kilgore. But he wasn’t sure he had the nerve to actually do it. He needed a nudge.

It came from an unlikely source. Days after Caldwell first read the play, his old student Joseph Magee showed up at his door. Two decades earlier, Magee had been a star high school quarterback in Tenaha, a small timber town about sixty miles southeast of Kilgore. He also captained the basketball and tennis teams, presided over the student council, made solid grades, and swept up acting awards for his performances in school plays, all while holding down a job on nights and weekends at a chicken hatchery.

After graduation, he enrolled at Kilgore College, where he was a promising drama student of Caldwell’s. But Magee was eager to see more of the world than East Texas, and on the last day of his freshman year he loaded up his blue Chevrolet pickup and drove to New York City, where he secured a summer job as an operations assistant at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. When summer ended, Magee decided to stay. He started a lucrative business that designed, imported, and sold textile patterns, and within a few years he’d met his future husband, Jay Rosenberg, who launched a successful fashion company. Together they traveled the world, summered in Nantucket, invested in real estate, and became patrons of the arts. Magee had everything. And yet he felt empty. He’d been diagnosed as bipolar, and when he tried cocaine for the first time, at the age of 35, he almost immediately became addicted.

Through it all, Magee kept in touch with his former teacher, who in 1986 founded the Texas Shakespeare Festival, which grew into a summer theater program that drew national talent to Kilgore. Caldwell often stayed in Rosenberg and Magee’s East Village penthouse when holding auditions for the upcoming season.

Still, Caldwell was surprised when Magee told him that he wanted to rejoin the college’s theater department and earn the associate’s degree he’d put off all those years ago. The decision seemed impulsive and ill-considered to Caldwell, who knew about Magee’s struggles; Magee didn’t hide the fact that he had recently completed an extended round of rehab. But Caldwell felt like he couldn’t tell a former student and dear friend not to reenroll in college.

Magee had seen Angels in America twice on Broadway, and his enthusiasm was infectious. “If I had asked anybody else around here about Angels, they would have said, ‘You can’t do that!’ ” Caldwell recalls. “But he was saying just the opposite: ‘Do it! Do it!’ ”

That settled it. Caldwell would direct the first half of Angels in America, titled Part One: Millennium Approaches. Magee would play a gay character named Prior Walter who contracts AIDS and, in an utterly wrenching storyline, is abandoned by his partner. Our Town it was not.

There have always been gay people in the Piney Woods, of course—Kilgore’s most famous native son, the world-renowned pianist Van Cliburn, being one. But Cliburn left East Texas as a young man, long before he came out, and he once said that teenage bullies made the Kilgore of his youth “a living hell.” Celebrated novelists William Goyen and Edward Swift and memoirist Robert Leleux have explored gay or sexually ambiguous themes with authentically East Texas voices and settings. But like Cliburn, they all left East Texas in order to make their creative marks elsewhere.

When I was growing up in Kilgore, in the eighties and nineties, I’d never, as far as I knew, met a single gay person. But we certainly talked about gay people. Stories of “fag-bashing” and “rolling queers”—drawing gay men in with false promises of sex or romance and then robbing them—were not unusual. Gay men, it was believed, carried lots of cash and would not fight back if accosted in city parks, on dark streets, or behind the gay bar on the edge of Longview, the larger town eleven miles up the road. Nor would a man living a closeted life dare to call the police and risk exposing his secret. Family members would disown him. He could lose his church community and possibly his career, even his life. It was the perfect crime.

In 1994, the night after Christmas, when I was a freshman at Sabine High School, two of my fellow students teamed up with two other young men from Kilgore to find a gay man—any gay man—and rob him. By the time my classmates and their friends were done, their victim, a middle-aged man, lay dead on the floor of his home from a shotgun blast to the chest. His brother, in town for the holidays, survived his own shotgun blast to the chest. Police found him sitting on the floor, holding his brother’s lifeless right hand. The following night, the police arrested the shooter, Mickey Goff, a scrawny youth who’d turned seventeen on Christmas Day. His accomplice, Lynn Duraso, was a big-boned teen I’d known since elementary school. When Duraso called home from jail, on a monitored phone line, he offered a simple explanation for why he’d gone along with the crime.

“They were fags,” Duraso said. “They were faggots.”

Still, despite such hostility toward gay people, when Caldwell decided to put on a production of Angels in America, he was able to find plenty of students at Kilgore College who were eager to participate (only two of his students declined). For the crucial role of Joe Pitt, a young law clerk who struggles to reconcile his attraction to men with his commitment to his wife and his devout Mormon beliefs, Caldwell cast a talented sophomore named Justin Adams.

Adams and I have been friends since kindergarten; we grew up in Baptist families down the street from each other. In junior high, Adams led prayer groups before school, with me as his faithful sidekick. We also performed a Christian skit called Soldiers of Light before audiences of church congregations and youth groups.

By high school we were considerably less zealous. Backsliding, you might call it. On a lark during our senior year, we signed up for an introductory theater class. I was a cutup who quickly ran afoul of the drama teacher, but Adams took it seriously. Onstage, in otherwise forgettable high school plays like Bell, Book and Candle, he was magnetic. And when we graduated from high school, he, like Magee, attended Kilgore College on a drama scholarship. Adams quickly became a favorite of Caldwell’s.

When Caldwell first spoke to the young cast of Angels, he insisted they show the script to their parents. Adams’s parents didn’t respond the way he might have hoped. They couldn’t understand why their son—whose girlfriend, Rainie, had been cast as the iconic angel who appears at the end of the first play—would choose to portray a homosexual onstage. His mother, concerned for his personal safety, not to mention the family’s reputation (Adams’s grandfather was a Baptist preacher in town), demanded that he drop out, but Adams refused. They had a terrible fight and didn’t talk for weeks. Unlike me, a born equivocator, Adams had no qualms about sticking up for what he believed in. What he calls his “journey away from the area” had begun in high school, when he was the only white starter on the basketball team. Adams was appalled at the way some members of our community treated his black teammates. And he took to heart the encouragement of his college teachers, who told him that it was okay to see the world differently than the people around you do, and that it was admirable to act on those beliefs.

No teacher at Kilgore College mattered more to Adams than Caldwell. If Caldwell felt so passionately about Angels in America, then Adams was in 100 percent. The script called for him to kiss another man, which surprised me when I heard the news. But Adams didn’t care. It was called acting.

At the time, I was the editor of Kilgore College’s student newspaper, the Flare. In September, we ran a story about Angels and its potential for controversy. “I know it’s risky,” Caldwell told our reporter. “I know to expect to get criticism, even reprimands. But it’s a matter of principle to me that we teach the students to learn to look beneath the surface, in this case the language or lifestyle to find deeper universal value.”

Our story was solid, but it needed a punchy headline. I pondered options that would catch the eye of potential readers walking past newspaper racks placed throughout campus.

“ ‘A Gay Fantasia’?” our faculty adviser, Bettye Craddock, asked when she saw my choice. “Wes, are you sure?”

I showed her a paperback copy of the script, of which I hadn’t bothered to read more than a few pages. The subtitle was A Gay Fantasia on National Themes. “It’s right there on the cover,” I said.

When Caldwell picked up a copy of the Flare that week, his heart sank. This was not good, he realized. Not good at all. Twenty years later, Joseph Magee still blames my headline for detonating the scandal that was about to tear my hometown in two.

Splashed across the front page, “A Gay Fantasia” caught the eye of Donald Beebe, the pastor of Grace Baptist Church, in Kilgore. He phoned Caldwell and asked if he could see the script. Beebe then wrote a scathing letter to the local newspaper, the Kilgore News Herald, claiming that Angels in America was “filled with vulgar and explicit scenes including two men embracing and kissing.” He called on East Texans to reconsider their financial support for the college, which had just announced a major gifts campaign, and encouraged others to petition their civic leaders to somehow stop the play.

Writing on the same page of the News Herald, publisher Dave Kucifer noted that while he’d neither seen nor read Angels in America, he also opposed the play on the grounds that it “deals with an alternative lifestyle foreign to Kilgore and the East Texas area.”

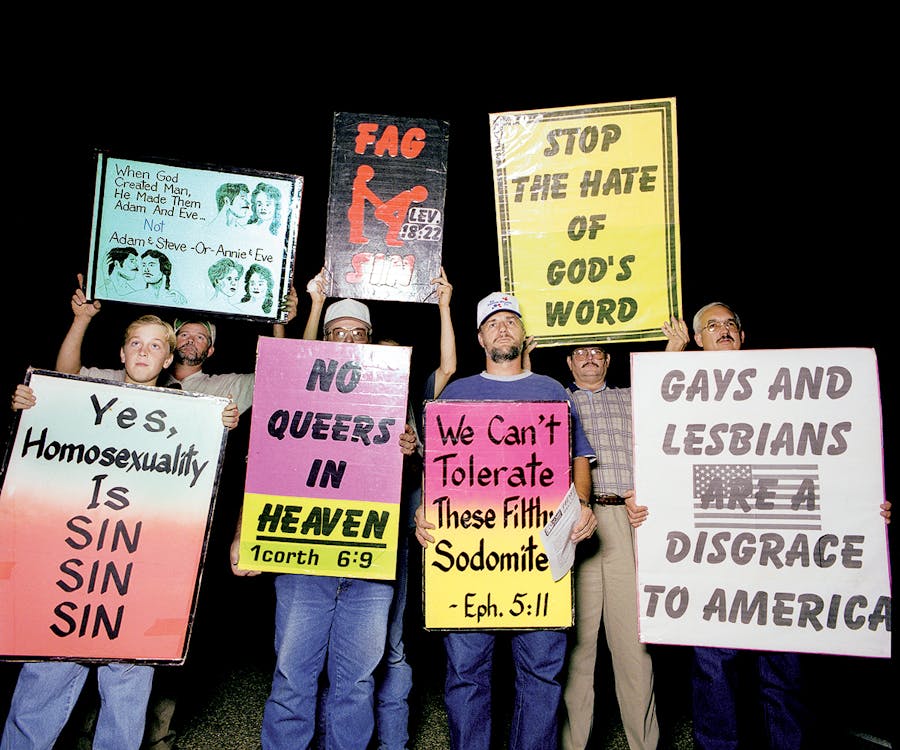

Word began to circulate around town. Churches passed along an excerpt from the play’s most graphic scene but failed to mention that Caldwell had already cut it. Faith Baptist Church updated the marquee in front of its chapel to read, “Say no way to the gay play at KC!” The rumors grew wilder by the day, with many folks hearing that nude college boys would be having sex onstage.

In Beebe’s opening salvo, he’d taken a personal swipe at the theater director: “One must wonder if Mr. Caldwell, himself, identifies with this character [closeted gay Mormon Joe Pitt].” The insinuation set off furious denunciations from a nationwide network of Shakespeare Festival friends and alumni in support of Caldwell, who had one adult son with his wife of several decades, Anna. Soon letters were pouring in to the area’s newspapers, by and large pitting local opposition—“You are indeed spitting in the face of the Lord by allowing this play to go on”—against outside support. As the uproar spilled beyond East Texas, journalists from across the state and nation descended on Kilgore.

Faith Baptist Church updated the marquee in front of its chapel to read, “Say no way to the gay play AT KC!” The rumors grew wilder by the day.

The media firestorm made me giddy. As a student journalist, I’d never come close to making a splash like this. And the fury only grew: The college was so deluged by phone calls, it installed an Angels in America hotline. More than 2,300 East Texans signed petitions protesting the play’s production. Although a couple of local clergymen eventually pushed back in media interviews, pleading for a ministry of love rather than denunciation, Kilgore First Baptist Church pastor Mark McClelland was emblematic of the righteous outrage sweeping across the Piney Woods. He told the Tyler Morning Telegraph that he felt like taking a bath after reading the play. “It was so dirty,” he said. The Houston Press reported that McClelland denounced the play from the pulpit and made copies of his anti-Angels sermon for sale. Politicians also jumped into the fray, with Kilgore’s mayor and Gregg County commissioners threatening to rescind funds they’d committed to Caldwell’s Shakespeare Festival. “As Christians, our freedoms are being infringed upon,” Mayor Joe T. Parker complained to the Dallas Morning News.

Kilgore College president Bill Holda refused to bow to the political pressure, vowing to defend educators’ right to teach any work of art or literature without fear of repression. The cerebral Indiana native did insist, though, to anyone who would listen, that Angels in America in no way glorified being gay. If anything, it did the opposite, he said, by painting a bleak picture of homosexuality during the AIDS crisis (a debatable and certainly incomplete assessment of a complex, metaphorical work).

Adams assumed the de facto role of spokesman for the student actors, who were unnerved by their community’s heated response. In an article printed on the front page of the News Herald, he took up the cause of gay rights while bitterly critiquing our neighbors for their “outburst of fear, disgust, and attempted censorship.”

Then the bus showed up. With opening night less than a week away, I watched through the second-floor window of the Flare’s office as a repurposed school bus, driven by a white-bearded mall Santa lookalike named Dorman McKinney, cruised slowly by, painted all black and adorned with crudely written billboards mounted on each side. The passenger side read, in part, “Hellp Gov. Bush calll the police!!! Dr. Molda [sic] and his sewer sucking sodomites at K.C. have raped & sodomized the virgin village of Kilgore TX.”

The bus circled the campus for hours as the driver and a handful of passengers shouted at students walking to and from class. Other times, McKinney would drive a pink ice cream truck into town and try to convince people that God was going to burn America just as he had Sodom and Gomorrah. “He showed me in a vision, and now I’m trying to warn the people,” McKinney told a Flare reporter who flagged him down. “But they won’t listen.”

He certainly tried to get us to listen. When McKinney discovered that Holda served as choir director for the First Presbyterian Church of Kilgore, he saw an opening.

“This guy shows up at our church,” Holda recalls. “Any woman that walked in with lipstick, he was calling them a harlot.” McKinney also used his bus to block Rangerettes from walking across the street. “Dancing whores!” he shouted. “Dancing whores!”

McKinney’s tactics backfired. “That kind of bizarre behavior drove a lot of these other fundamentalist church people back into the shadows, because they didn’t want to be identified with this idiot,” Holda noted.

Despite the backlash against McKinney and his ilk, the protests were taking a toll on Caldwell. He was shaken when he received an anonymous letter to his home that ended “Maybe you’ll die of AIDS too.” Caldwell had grown up in rural Arkansas and East Texas, where he had always been nagged by a sense that he didn’t fit in. He loved songs and stories, but his father, a sawmill worker and Baptist deacon, didn’t allow the family to see movies or plays. “He thought all that was frivolous and a waste of time,” Caldwell says. Much later he would learn that, behind his back, his father had nicknamed him Funny Boy.

When Caldwell first read Angels in America, he and Anna were experiencing a difficult period in their marriage. A real estate investment involving a family member had gone south, which cost them their home. “There was a lot of silence, a lot of unspoken issues,” he recalls. At the height of the outrage over Angels, Anna confronted her husband, asking him if producing the play and turning his community upside down was his roundabout way of coming out of the closet. Caldwell told her no. Later, he would think of all the things he wished he’d said instead. But then and there, he had never felt more alone, and his courage left him.

Joseph Magee was not faring much better. “I had lived in New York City for twenty years, and I forgot this is the way people thought in rural America,” he recently told me. “I didn’t understand why people would get so angry. Instead of healing old wounds, it opened them all back up. It was really devastating to me.”

It didn’t help that the 38-year-old Magee felt alienated from his fellow troupe members. Not only was he twice the age of the other actors, he was the sole member of the cast who was openly gay. He’d lived through the AIDS crisis and was scarred by his experiences as a volunteer caring for men who had contracted the virus. “These people died on me left and right,” Magee said. And now he was supposed to play an AIDS patient? “Some part of me, I think, didn’t want to die of AIDS in that play.”

Perhaps that’s why Magee, the onetime bright light of the Tenaha High School drama program, still hadn’t managed to learn his lines. Caldwell suspected—correctly, as he later learned—that Magee was showing up high to rehearsals. Three days before opening night, he failed to appear at all. Caldwell was teetering. On behalf of the cast, Adams confronted his director. The play, he said, was heading for disaster. They simply couldn’t rely on Magee.

Caldwell had avoided rendering such a judgment on his old friend, but in that moment he realized, for the sake of the play and his cast, that he had to replace Magee. Farris Craddock, a recent alum of Kilgore’s drama program, would take the stage in his place: “I called Joey in and told him, ‘I can’t use you, Joey.’ He went crazy, just crazy.”

That night, Magee made cardboard posters, snuck into the college’s theater building, and placed them around Caldwell’s office. When Caldwell arrived at work the next day, he was confronted by signs that said things like “I love you. I hate you. I want to be like you. I want to be anything but you.”

Magee felt more than rejected; he felt betrayed. The play, he was sure, never would have happened without his initial encouragement. He’d even arranged for his husband to ship designer suits for the men’s costumes from New York, not to mention yards of costly white fabric for the angel’s costume. Magee had phoned the American Civil Liberties Union, which stood ready to file an injunction should the college attempt to cancel the play. And now he was being pushed out of a production he’d given so much to?

“I can’t tell you how traumatic it was,” Magee said. “I fantasized about hanging myself in front of the theater the night it opened. But then I thought, ‘Raymond will never forgive himself. He’ll think it’s his fault.’ ”

Magee’s husband called and begged Caldwell to reinstate Magee. Rosenberg and their friends had already booked plane tickets to see the show. Caldwell refused. “I don’t know how you put up with this,” Caldwell said.

“I love him,” Rosenberg said. The answer rocked Caldwell. “I had to admit to myself, I don’t love anybody that much,” Caldwell recalled. “I couldn’t have put up with that from anybody.”

Utterly despondent, Magee absconded with a friend’s pickup truck. No one knew where he’d gone or what sort of danger he might be in. The new lead in place, the remaining cast members kept their focus on the production. The show, as everyone knows, must go on.

Despite the international attention drawn to their protests, the outraged townsfolk couldn’t prevent the curtain from rising on October 14, 1999, at—yes—the Van Cliburn Auditorium. The Chronicle of Higher Education reported that, in a last-ditch effort to hinder attendance, Kilgore lawyer Glenn D. Phillips, the town’s municipal judge, and two other local businesspeople purchased tickets for 150 of the theater’s 263 seats. “The play may be award-winning in New York, but down here, we look at things a little differently,” the Chronicle quoted Phillips as saying. “It’s ironic that the courts tell us we can’t have prayer in schools, but tax-supported colleges can put on that kind of trash.” (Today, Phillips says that he simply bought the tickets on behalf of the two businesspeople and donated them back to the college by giving them to Holda—though Holda disputes that claim, and a contemporaneous story in the Tyler Morning Telegraph essentially confirms the Chronicle story. Phillips also says that he does not think he said the quote the Chronicle attributed to him.)

The alleged gambit failed, because Caldwell instructed the box office employees to resell any tickets not claimed ten minutes prior to the show. And, in fact, the auditorium quickly filled to capacity. Outside, TV crews and protesters lined the highway. Some of the picketers held signs depicting stick figures engaged in sodomy; as Holda noted, they were far more explicit than anything the actors would be doing inside the auditorium.

Wary of violence, police locked down the theater, and the actors were ordered to stay in the greenroom in the basement until the performance began. Adams’s adrenaline pulsed. He was ready for bombs, anything, but he also took heart from a letter that Kushner, the playwright, had faxed to the cast that day. “Don’t get chuffed-up and fill the play with anger, which attacks on your work may have generated; part of the strategy of the enemies of art is to create toxic environments in which the art, even if on display, can’t be properly received,” the letter read in part. “Trust in the play, in your work, in your talent, in the audience.”

Now, as the rising of the curtain approached, Caldwell stood with his actors in the basement, gave them one last pep talk, and reminded them of the plan the police had put in place: in the event of a disruption, he was instructed to shout, “Hold!” and the actors would run from the stage and lock themselves in the basement.

Having done what he could to prepare his students, Caldwell walked upstairs to take the stage and introduce the production. He was apprehensive; he knew full well that protesters might be right there in the house, ready to cause disruption. But when he walked out from the wings, the audience greeted him with a standing ovation.

Magee was among them. He had reappeared for the premiere, although the truck he’d taken was now riddled with bullet holes. He had tried to score drugs, he said, but the deal went bad. “These guys in Longview opened up a bunch of pistols on me and put tons of bullet holes in the truck,” Magee later told me. “One bullet went through the glass, in front of my face, and out the other window.” Wearing pajamas, he sat in the front row and cheered on his former castmates—at least in his recollection. Caldwell remembers Magee sitting there and glaring at the stage.

That first night, the production went off without a hitch. And when the play ended, Caldwell and the cast were awarded with another standing ovation. The next three nights drew sold-out, enthusiastic crowds as well. Adams’s mother, Patricia, saw the play three times. She’d begun to have a change of heart about his participation after having a lengthy conversation with Caldwell, who reassured her that he would never do anything to hurt her son. And she was offended by the town’s visceral reaction to Angels in America. “These people who thought they were doing good were doing more harm than they ever knew,” she said. “It’s sad what people do in the name of religion.” But most importantly, she loved Adams and knew that she couldn’t let a play come between them. “I thought, ‘Well, if he’s brave enough to do it, I’m not gonna be the one who stands in the way.’ ”

“These people who thought they were doing good were doing more harm than they ever knew,” Adams’s mother said. “It’s sad what people do in the name of religion.”

As for me, I didn’t actually make it to any of the four official performances. Instead, at Caldwell’s invitation, the Flare staff watched the final dress rehearsal. I remember walking with a few of my friends across campus toward the theater, but I didn’t have any strong feelings of anticipation or trepidation. I just wanted to see for myself what had sparked so much outrage. A conversation with a friend’s mother, a few weeks earlier, was also on my mind. She had questioned me about my decision to transfer to the University of Texas at Austin the following year. “Why do you want to go to Austin with all them gays?” she asked. I mumbled something bland and noncommittal about the quality of UT’s academics.

That was the world I lived in when my friends and I took a seat near the rear of the dark and all-but-empty auditorium, as the curtain rose and the stage lights came on. Caldwell sat in front, closely observing the actors onstage. I watched as Prior, the character Magee was meant to play, was abandoned by the boyfriend who couldn’t bear to watch his health and mind deteriorate. Joe Pitt, the closeted Mormon, desperately tried to follow his religious beliefs but failed time and again. My nineteen-year-old self thought it would be hilarious to see my friend kiss another man; it wasn’t. Pitt, like the rest of the characters, was smart and funny, hurting and lost. As someone who’d tried to hide my own struggles and doubts behind a veneer of youthful apathy, I could relate. I wasn’t watching a play about some incomprehensible figures who lived in a place far removed from anything I knew. I was watching the stories of people who felt real to me and who persisted through pain and personal torment more severe than anything I had experienced.

I was swept up in the drama when, suddenly, the performance jolted to a conclusion as a beautiful angel crashed through the ceiling of Prior’s bedroom and delivered a stirring, if enigmatic, proclamation: “Greetings, Prophet! The great work begins! The Messenger has arrived!”

I had no idea what that meant, but in that moment, the fears of the protesters had come true. Dark magic hadn’t turned me gay, but a work of theater had cracked the Pine Curtain, stirring in me the first inkling that gay people deserved to be treated with dignity and love rather than cruelty or cold indifference. Forced to choose between the hate-filled protesters outside the theater and the searching, brave people inside, I knew which side I wanted to be on. The messenger had arrived.

While chatting with old friends recently, I have discovered that my world-view wasn’t the only one transformed by the arrival of Angels in America in the Piney Woods twenty years ago. Danea Males, then a photojournalist for the Flare, whose father had not allowed her to see the play, says that photographing the protests was the first time she stepped away from the fundamentalist church she’d grown up in. “It was a defining moment,” she says. “I wasn’t supposed to question things. I was supposed to have faith that guided my path. But the petitions and the protests—they were so ugly and mean-spirited.” Today, Males is an art professor at a university in South Carolina.

Last spring, I was visiting family in Kilgore when Adams, through sheer coincidence, also happened to arrive in town. A longtime New York resident, he’d just completed the twelve-week run of a play in Florida called Straight White Men, and he’d come to East Texas to see family too and to talk with a local film producer who was interested in a movie script he’d written about Kilgore’s brush with Angels. We met at a pool hall in Longview. Through the haze of cigarette smoke and the crack of billiard balls, he could still recite his favorite line from the play: “From such a strong desire to be good, they feel very far from goodness when they fail.” It was a sentiment that strongly resonated with Adams, who, long before he took on the role of the spiritually tormented Joe Pitt, had twice asked God to save him. “My grandfather baptized me, and I didn’t think it was good enough, so I got baptized again,” he said. “I didn’t resonate with being gay, necessarily, but I resonated with trying to fit into something you don’t fit into”—namely, for him, fundamentalist theology and stifling small-town culture.

Four months after Adams appeared in Angels, his uncle Jason killed himself. Adams had no idea his uncle was gay, nor that he had AIDS. “When that happened,” he said, “I was galvanized.” Upon leaving Kilgore, he was accepted into London’s prestigious Royal Academy of Dramatic Art, from which he graduated in 2003. “Angels in America defined who I am,” Adams said. “All my career, I’ve tried to be a torch for marginalized people.” In 2012, Adams wrote and directed an off-Broadway play titled The Man-Made Rock, about repressed East Texans. Joseph Magee, who over the years had made his peace with Caldwell and everyone involved with Angels, was the major backer of Adams’s production.

Adams’s mother was changed by the experience too. “It opened my eyes up,” she said recently. “Justin’s an actor, he’s around all sorts of people, and I have really become fond of them—it’s not my business if they’re gay. I like them as a person, and I’m not gonna judge them. There was a time I did. I was worried what other people would think.”

Adams’s activism has long outlasted that of the protesters, who abandoned their cause before the end of the four-night, sold-out run. The Gregg County Commissioners Court did make good on its threat to yank financial support from the Shakespeare Festival, though. “What comes to my mind when I think of Shakespeare are folks with some spears,” Commissioner Danny Craig told the Houston Press, admitting that he’d never seen a Shakespeare play. Donations from theater supporters around the country more than made up the difference, as did a check presented to Holda when he received a PEN/Newman’s Own First Amendment Award for his refusal to cancel the play.

“I would not want to go through it again, but I don’t regret having taken a stand,” Holda says now. “Without the confrontation that occurred, Kilgore might not have awakened as quickly to the realities of its own community. The world was changing.”

“What comes to my mind when I think of Shakespeare are folks with some spears,” Commissioner Danny Craig told the Houston Press, admitting that he’d never seen a Shakespeare play.

Indeed, in 2003, less than four years after Kilgore’s production of Angels in America, the U.S. Supreme Court struck down the Texas statute outlawing sodomy, a landmark civil rights decision. Two years later, Caldwell staged The Laramie Project, a play about the murder of Matthew Shepard, a gay university student in Wyoming. This time around, there were no letters to local newspapers, no picketers, no complaints.

Kilgore’s current mayor, Ronnie Spradlin, saw Angels in America on opening night. These days, he says, “I have people that move here who say Kilgore is the most accepting, welcoming, nonjudgmental town they ever lived in.”

As much as I adore my hometown, and East Texas in general, I don’t know that I would go that far. The area produces some of the warmest and most caring people you will ever meet, but we also pump out a seemingly endless stream of cruelty toward people who stray from the rules and roles we’ve set down. That wasn’t the main reason I moved away from the region nearly a decade ago, but it’s part of why I haven’t given more than a fleeting, nostalgia-tinged thought to moving back.

It’s easy for me to pick apart the flaws of others, of course. It’s harder to look inward. For years, I bristled at criticism that I sensationalized the Angels controversy by giving the story that “Gay Fantasia” headline and putting it on the front page of the Flare. The headline had served its purpose, I argued, drawing attention to a hot-button issue. As I’ve grown older, though, I’ve come to see my own motives more clearly: because I always got such a kick out of stirring up trouble, I’d egged the oppressors on, with no regard for the people who ended up as the target of all that hatred. As the paper’s editor, I could have met my journalistic obligations without fanning the flames quite so high. (Caldwell, with typical generosity, later told me that the play would have been controversial even without my intervention, though perhaps less so.)

But if I’ve grown over the years, I think Kilgore has too. Mayor Spradlin is illustrative of the town’s evolution. At the height of the “gay play” hysteria in 1999, he wrote a letter to Caldwell thanking him for producing Angels in America. When the student actors were locked in the basement on opening night, he realized they were thirsty and rushed to his lumberyard to fetch a water cooler. But Spradlin was a quiet supporter. Almost no one who lived in Kilgore dared to publicly defy our Baptist preachers. In 2019, though, Spradlin feels comfortable calling them out for what he sees as their narrow-mindedness; he describes the targets of their attacks as persecuted martyrs.

A few years ago, my wife and I made a quick trip to East Texas from our home in Austin to attend a cousin’s wedding. Shawn had lived in the closet for decades. Then, at the age of 42, he met Terry, the man he loves. Some of our family members declined to attend the wedding, which was their right and also their loss: it was a joyous ceremony. The grooms exchanged vows before an arbor of green boughs and Spanish moss at Shawn’s progressive church in Longview. He and Terry aren’t welcome everywhere, but they feel comfortable spending their lives together, openly, in Kilgore.

This story could have ended right there, wrapped up in a neat little bow: a transgressive work of art landed in my hometown, stirred up controversy, and did exactly what we all want art to do, transforming dozens, perhaps hundreds of people who experienced it. But though many of us got to learn some valuable lessons and move on, at least one person central to the controversy didn’t get that sort of closure.

Sometimes art has a more complicated legacy than merely helping us see the world with a new pair of eyes. Sometimes it gets under our skin, exposes our deepest fears and most intransigent ambivalences. And sometimes it offers no resolution. In fact, it often does the opposite: it leaves us with a more vivid sense of the choices we’ve made in our lives, the choices that have been made for us, and how difficult it can be to tell the two apart.

The morning after our night at the pool hall, Adams and I paid a visit to Caldwell at the headquarters of the Texas Shakespeare Festival. Now 77, he’s aged well, mostly unchanged but for a neat goatee to replace the mustache I remembered. During the course of a sprawling, hours-long conversation, he brought up the moment when his wife, Anna, asked him if he was gay. Caldwell had said no. But what he had wanted to do was respond with the same question Joe Pitt asks his wife in Angels in America: What difference does it make?

Caldwell seemed to drift away as he channeled a conversation running through his mind. “If we have loved each other all of these years,” he said, “why are you asking me such a thing? What’s the point? Do I love you? Yes, terribly so. Do I want to be apart from you? No, never.” If he treasured the life and the son they had created together, if he wanted to remain by her side and no one else’s until the day he died, shouldn’t that be enough?

Over the years, Caldwell said, he has come to believe that sexual orientation is only one component of a long life, and not the most important one. Nor does he find that labels are particularly useful. “Do I act out on any urges that I may have had much more when I was younger?” he asked. “No. Have I? No. Would I want to? Not really. But do I acknowledge that part of my humanity? I acknowledge it. But do I act on it? No. So why can’t we live with that?”

Acknowledging that his life might have been much different if he’d been raised in a more tolerant time and place than his sternly religious household in Arkansas and East Texas in the middle of the twentieth century, he began to sound like a character from Angels in America whose climactic monologue never made it into the script. “You don’t know what the other road would have been,” Caldwell said. “I have loved people deeply, painfully so. Mostly unspoken, unexpressed, secretly, and without shame—just adoring their spirit and their courage. And I’ve often wondered, Could I have expressed that successfully in some other way, along the route of my life? I don’t know. Maybe. Maybe not.”

He continued to speak, elliptically, about a void that he could neither fill nor fully articulate. “I thought the play said a lot of those things,” he said. “They resonated. They more than resonated. They drilled into me. They frightened me, they provoked me, they made me angry and sympathetic, every emotion. I read it and thought, ‘Who is this man? Who wrote this? I need to know him. He has no right to write this.’ ”

There was something there, half-hidden in Kushner’s script, that he had to acknowledge and deal with. So he dealt with it and compelled the rest of us to do so as well.

Caldwell had felt twenty years ago that he’d had no choice: this was not a play he could ignore. There was something there, half-hidden in Kushner’s script, that he had to acknowledge and deal with. So he dealt with it and compelled the rest of us to do so as well.

Weeks after Kilgore’s production of Angels in America drew to a close, Anna served Caldwell with divorce papers. In hindsight, he says, he shouldn’t have been shocked; the controversy over the play and the attacks on her husband had been tremendously difficult for Anna. But he was shocked, even so. He sold the home they had bought a year earlier and rented a smaller one, in a less affluent neighborhood. He settled in for what he thought would be a new, bleaker chapter in his life.

Then, a few weeks later, Anna came back. They bought another house, and slowly their marriage repaired itself.

In the years before and since, Caldwell has often dreamed of leaving East Texas, but he had the festival to think of and the life he and Anna have built. And there was one other thing that has kept him in Longview for so long: “Fear, I guess.” So he stayed.

This article originally appeared in the November issue of Texas Monthly with the headline “Angels in East Texas.” Subscribe today.