It was late fall, but Cheryl Clark was already excited for the next baseball season. She had received an email from the sales department of her beloved Houston Astros inviting her to an open house at the ballpark. Cheryl knew it was part of a sales pitch aimed at tempting her to buy season tickets, but it also included a tour of the locker room, and that sounded like fun. “Why not?” she thought. So on a cool day last November—exactly one month after the Astros’ 2015 season had ended in yet another playoff heartbreak—she drove downtown to Minute Maid Park with her twelve-year-old daughter, Kayla. They were mostly going for the tour. As much as she loved the Astros, Cheryl had no intention of purchasing tickets that day to all 81 home games for the upcoming season. “At most, I was thinking of a twenty-eight-game package,” she said.

But as the Clarks toured the cavernous ballpark with its thousands of empty green seats, the temptation to buy into the Astros grew.

Their sales rep—a young man who looked about fifteen—took them to the Mazda Club Level, about halfway up the seating bowl. The area had been renovated the year before, and among the improvements were changes to the concourse so that fans waiting at the concession stands could see the game. The view of the field was exquisite. “Mom, these are amazing seats!” Kayla said. But Cheryl was still not sold. The rep said he would next take them down to the field level and asked if they’d prefer to see the view from the third- or first-base side. That was an easy question to answer.

Their preference for sitting behind first base went back a long way. Many years ago, when Cheryl attended games with her mom, Florence, that was where they sat in the Astrodome. Flo would buy tickets for the upper deck, and kindly ushers they had befriended would let them descend, via a staircase hidden deep in the bowels of the Dome, to the lower-level seats, usually along the first-base line. It happened often enough that Cheryl still felt sentimentally attached to that ballpark vista.

In her family, baseball was a maternal thing. Her dad was more of an Oilers fan, and so at Astros games, it was always mother and daughter. When she wasn’t at the Dome, Cheryl tuned in to hear Milo Hamilton call the games. “I loved listening on the radio,” Cheryl said. “I loved it.” She recalls being at summer camp during her high school years and listening to crackly broadcasts.

Cheryl remembers those days as some of the best of her life. She went to games with her girlfriends, and they would hang banners, some of them attracting official censure, including one they’d displayed when the Astros were managed by Hal Lanier. “I am still kind of proud of that one,” she said. “ ‘The Dodgers are Lasorda good, but the Astros are a Hal of a lot better.’ Can you believe they took that one down? They said it was too close to profanity.”

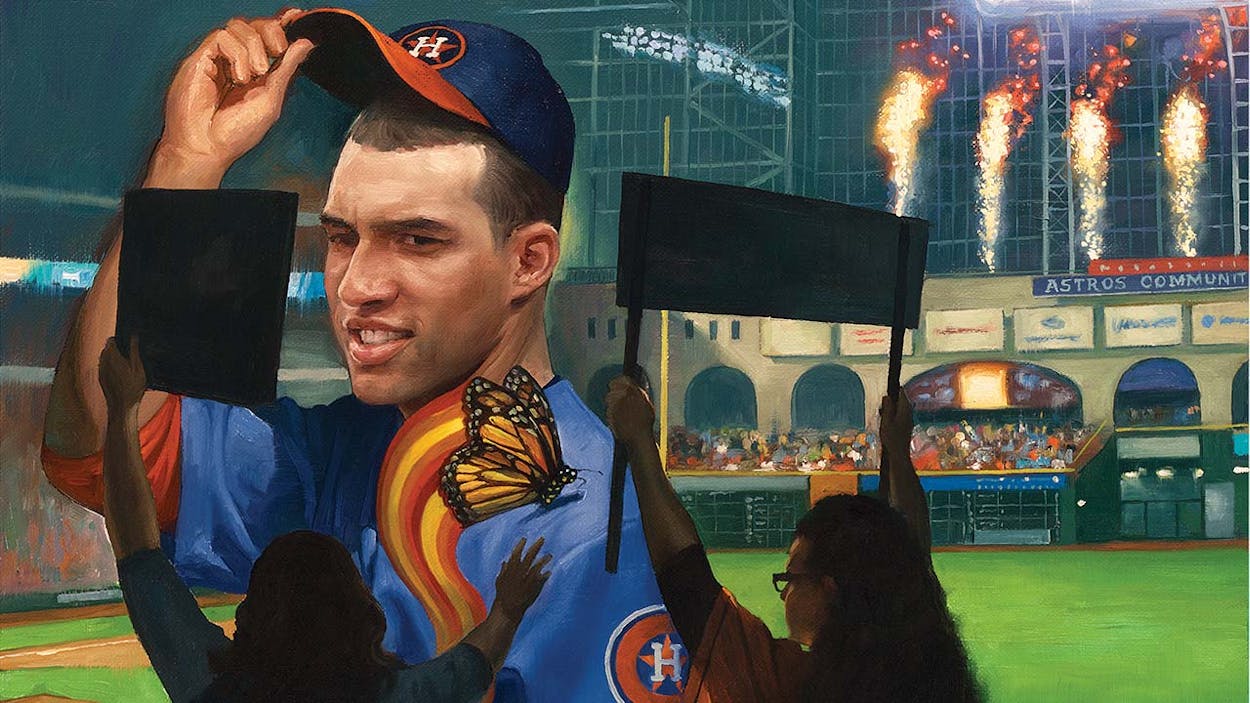

Those good times were on Cheryl’s mind as the sales rep led them to the seats along the first-base side. Flo had died in 2009, but Cheryl and Kayla still felt her presence. Every time they saw a butterfly, they would say it was Grandma fluttering past for a visit.

And it was comforting that Flo’s love of baseball had found its way to her granddaughter. Just as she had with her mom, Cheryl began to attend games with Kayla; they went more frequently after her divorce from Kayla’s dad, in 2015. “Last year was when she really tuned in,” Cheryl said. “And I was like, ‘Okay, I am not trying to push my love for this team and my fanaticism on you. I only want you to go if you really want to go.’ And she just looks at me like, ‘Really?’ She is a full-blown fanatic.”

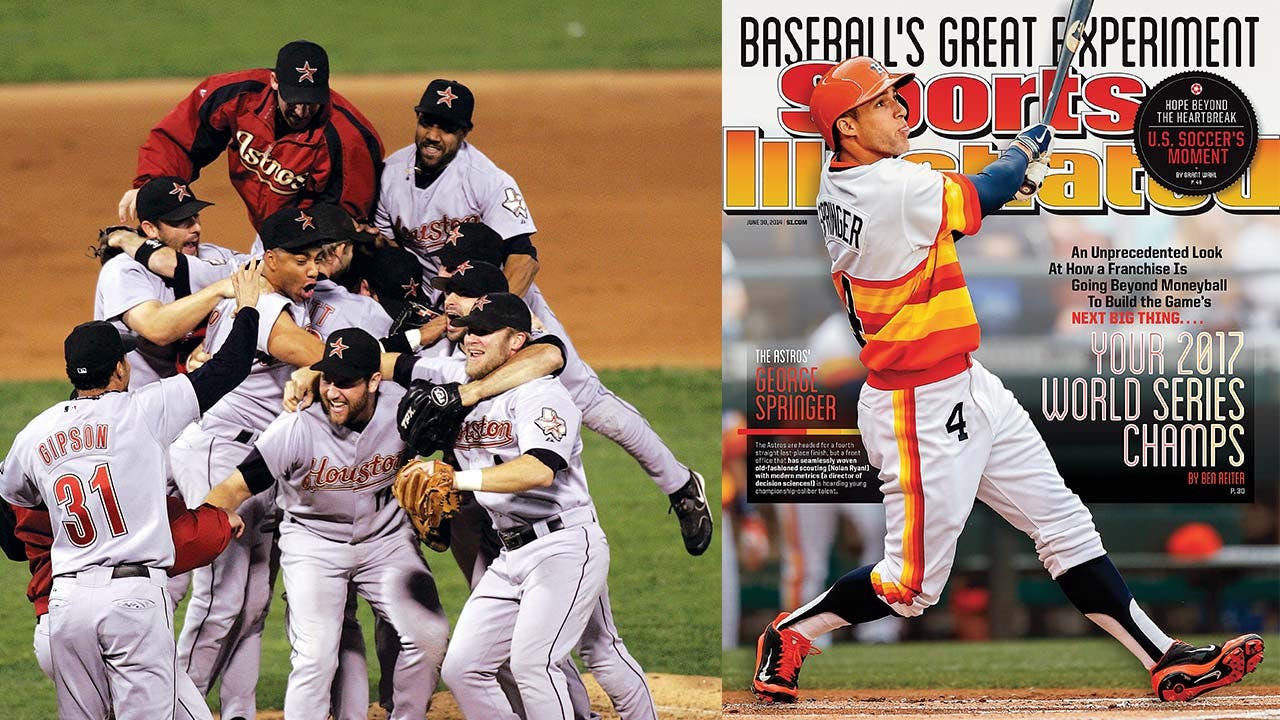

They had attended a dozen or so games in 2015, and what a season it had been. For the first time in a decade, the Astros had made the playoffs, a sudden, shocking rise from baseball laughingstock to contender. The team had assembled a lot of young talent under the guidance of new owner Jim Crane and his sharp, bilingual general manager, Jeff Luhnow, but even the most optimistic forecasts couldn’t have predicted the Astros would be so good so soon. In June 2014 Sports Illustrated had run a cover story that labeled them—coming off a Major-League-worst 111-loss season—“your 2017 World Series champs.” As if to emphasize the boldness of the contention, outfielder George Springer was pictured on the cover in a throwback orange-rainbow jersey, a crazy, provocative uniform to match what some then considered an insane forecast.

As the Astros entered the playoffs in 2015, it appeared SI had been wrong, albeit in a way few expected. It looked as though the team might triumph two years early. On October 12, ahead two games to one in their best-of-five division series with the Kansas City Royals, the young Astros held a commanding 6–2 lead after seven innings. But it was not to be. The bullpen melted down. The Royals crossed the plate five times in the eighth and twice more in the ninth to tie the series and then finished off the Astros two days later in the decisive fifth game. A few weeks after that, the Royals won the World Series.

Wait till next year, Astros fans.

This was another of the sorts of late-inning collapses Astros fans have come to expect from this most star-crossed franchise, but it didn’t sting quite like the others. For once, a Houston team had exceeded all expectations. After years of losing, the ’Stros were once again playing ball on crisp October nights. Better still, their stars were all twentysomethings: Springer and golden child shortstop Carlos Correa, pint-size dynamo José Altuve at second base, black-bearded pitcher Dallas Keuchel, Houston’s first Cy Young Award winner since Roger Clemens, in 2004. Unlike the heartbreaks of 1980, 1986, 2004, and 2005, this one seemingly foretold better times. On the fan site Crawfish Boxes, blogger Jason Marbach put it this way: “Chin up, Astros fans. The future is incredibly bright in HustleTown.”

Maybe 2016 really would be the Astros’ year at long last, Cheryl thought to herself, the rep next to her. They were still standing on the first-base side, about midway between the end of the Astros’ dugout and the right-field warning track. This spot reminded Cheryl of where she used to sit with her mother, and it was also near the patch of outfield patrolled by Springer, her favorite Astro since Bill Doran and Kayla’s favorite Astro ever. (“I like him the best because he is a great player and role model,” Kayla had told me. “He has a stutter, but he is not afraid to go in front of cameras and give interviews.”) Yet Cheryl still wasn’t quite ready to commit.

She was chatting with the sales rep, who seemed to have little hope of making a sale, when Kayla interrupted them with a shout, one her mother thought rude at first.

“Hey, Mom!” she said. “There’s a butterfly!”

And there it was, trembling through the air in the middle of fall inside the ballpark, a monarch butterfly.

Cheryl turned to the Astros guy. “Okay,” she said.

“Okay what?”

He looked confused. “I don’t think he believed he was going to be making a sale with us,” Cheryl would later recall. “And I said, ‘Okay, I’m buying ’em.’ And then he took us to a little table, and I signed my life away.”

Not all of us have done so with money, but in a sense, every true Astros fan has signed his or her life away. What team has come so close more often with nothing to show for it, save for one measly pennant?

The franchise that would become the Astros debuted the same year Bob Dylan did: 1962. At first they were known as the Colt .45s but ditched that moniker when they moved to the space-age confines of the Astrodome, in 1965. The early years were as bad as you’d expect from an expansion team, but it was stockpiling young talent. In an alternate universe that did not have Spec Richardson as general manager, the Astros would have been kings of the National League for much of the seventies.

Instead, via a series of lopsided trades, Richardson frittered away Joe Morgan, Rusty Staub, John Mayberry, Mike Cuellar, Mike Marshall, and Dave Giusti. Morgan went on to become a Hall of Famer, and Staub was a six-time All-Star. Mayberry was an American League MVP runner-up, and Cuellar won twenty games as a pitcher several times, once for a World Series–winning Baltimore club, and a Cy Young Award. Marshall also won a Cy Young, and Giusti became a top relief pitcher.

Meanwhile, the Astros missed the postseason every year until 1980, the season I became a fan. I was ten. My grandparents had season tickets that year in the Astrodome’s mustard-yellow upper deck. Every time the boys were in town, we would pile into my grandfather’s boat of a Buick and head down South Main, past the streetwalkers and hot-sheet motels to the west entrance of the Eighth Wonder of the World, where the arms of Nolan Ryan and Joe Niekro and the legs and gloves of Cesar Cedeño, Terry Puhl, and José Cruz would take us to the playoffs. Leading the series two games to one, a win away from the pennant and the World Series, the Astros lost two straight thrilling extra-inning games to the Philadelphia Phillies.

Still, at that point, we were all just happy to have been there. Wait till next year.

Except they wouldn’t get that close again until 1986. That team had strikeout masters Ryan and Mike Scott and a mix of veterans like Cruz, Phil Garner, and Flo’s favorite Astro, Denny Walling, providing leadership for youngsters like Doran, speedy Billy Hatcher, slugger Glenn Davis, and well-rounded outfielder Kevin Bass.

Scott clinched the NL West in unprecedented style: a late-September no-hitter against the San Francisco Giants, which set the stage for a battle with the famous Mets team featuring Dwight Gooden, Darryl Strawberry, Keith Hernandez, and Gary Carter.

Scott was masterful, surrendering just one run in winning games one and four. The Mets took the other three. If only the Astros could win game six, the unhittable Scott would take the hill again for a deciding game seven, but if they lost, curtains.

In sixteen innings, still the longest National League Championship Series game on record and one of the most memorable in baseball history, the Astros lost. Mets lefty Jesse Orosco struck out Bass with the potential winning runs on base.

“I remember it was college night at St. Thomas High School that night, and I was watching the game while I was putting on my makeup,” Cheryl said. “After Bass struck out, I was crying my eyes out, and I had to reapply my makeup.”

Wait till next year, Astros fans.

Or maybe a decade: that was how long it took for the ’Stros to get back in contention. Between 1997 and 2001, the Astros, led by Craig Biggio and Jeff Bagwell, won a grand total of two playoff games and lost twelve. The “Killer B” offense put up a collective sub-.200 batting average over those four series, and after 2001, the Astros’ all-time postseason record stood at 8-22, with zero series wins.

That would not change until 2004, when hometown heroes Andy Pettitte and Clemens joined Roy Oswalt in one of the best pitching rotations the club ever had. By season’s end, the Astros offense also had a murderers’ row of Bagwell, Biggio, Lance Berkman, Carlos Beltran, and Jeff Kent.

And, finally, Houston managed its first playoff series win, in eight tries, one that came at the expense of its old nemesis, the Atlanta Braves, to boot.

Next up, a newer archfoe: the St. Louis Cardinals.

The Cards took the first two in St. Louis. The Astros took the next three in Houston. We were once again a game away from the World Series, and Beltran was playing out of his mind, homering in each of the first four games. Back in St. Louis for game six, the Astros trailed the Cardinals 4–3 in the ninth, but this time it would be the Astros who forced extra innings, with Bagwell redeeming a career of poor postseason play with a clutch RBI single.

Here we were again in extra innings, needing just a run and three outs to clinch. The Cards’ Jim Edmonds had other plans. He ended game six with a walk-off homer and turned the tide of game seven with a diving over-the-shoulder catch of a Brad Ausmus drive to left-center that would have put the Astros up 3–0 in the second inning with Clemens on the mound.

Wait till next year, Astros fans.

With Clemens, Pettitte, and Oswalt returning and the unhittable Brad “Lights Out” Lidge in the bullpen, the Astros were still contenders in 2005. After a start so terrible that the Houston Chronicle published a graphic of a tombstone reading “RIP Astros’ season” on June 1, the team inexplicably caught fire, going 70-41 the rest of the way and landing a wild-card spot.

The Astros again won the first round and again faced the dreaded Cardinals, which produced another defining moment for long-suffering Astros fans.

In game five, the Astros were once more a few pitches away from their first pennant, holding a 4–2 lead in the top of the ninth. The Redbirds had two men on. At the plate: Albert Pujols, the decade’s most intimidating slugger. On the hill: our invincible fireballer, Lights Out Lidge.

In sports bars and living rooms from Beaumont to Columbus, Corpus to College Station, and there among the screaming hordes in the ballpark on Crawford Street, Astros fans watched, nostrils flared, eyes wide-open, as Lidge faced down Pujols with a trip to the World Series in hand, and, and, and . . . well, you probably know the rest. We watched Pujols launch a sloppy Lidge slider into low freaking orbit.

High in the left-field upper deck, three generations of Cheryl Clark’s family bore stunned witness to the three-run blast as it hurtled past them at eye level.

“The silence was unbelievable,” Cheryl recalls. “My mom, my brother, we all saw the ball hit. Kayla was there too, at age two. Heard the clunk. I just stared at it and was like, ‘Whyyyyyy?’ You physically felt it, like someone punched you in the gut. We didn’t breathe.”

Cardinals 5, Astros 4.

As Pujols rounded the bases, Cardinals announcer Mike Shannon enthused, “This could be a crushing blow, a crushing blow, to the Houston club!”

Except it wasn’t. At least not at first. The next night, Oswalt came out and made mincemeat of Pujols, and the Astros won the game and the series. After decades of frustration, the Astros had finally won the pennant and were going to the World Series. Maybe this would finally be our year!

Nope. They were swept by the Chicago White Sox in one of the least-memorable World Series ever. Lights Out Lidge got lit up in two of those games, one thanks to a walk-off homer by a guy named Scott Podsednik, who had a grand total of zero home runs in 568 plate appearances during the regular season.

As the light-hitting Podsednik rounded the bases, Fox announcer Tim McCarver could only marvel: “How do these things happen?”

That’s easy. The Astros happened. Trust the Astros to finally reach the World Series and get swept by a team that hadn’t won a title since Woodrow Wilson was in the White House. Shannon had been right: the Pujols blow was crushing, and it crushed the organization for years to come.

“Nationally, nobody remembers we ever went to a World Series,” says Houston baseball historian and author Mike Vance. “And even for us, it was such an anticlimax. It’s weird. You make it to the World Series, and we’ve only done it one time, and that’s not even the thing you remember. In fact, the thing you remember from that season is a really negative moment.”

It was just one more devastating blow that this city’s sports fans had endured over the years. No Super Bowl appearances or World Series wins. The blown call on Mike Renfro’s touchdown grab for the Oilers in their tough loss to the Steelers in the 1979 AFC title game. The Lorenzo Charles dunk at the buzzer that brought down the Phi Slamma Jamma Houston Cougars, probably the greatest team in NCAA history to have not cut down the nets. The Oilers titanic catastrophe in Buffalo, blowing a 35–3 lead in the playoffs to a backup QB. The Rockets being almost but not quite good enough to take down the Celtics twice in the eighties, and when they finally did break through, in the nineties, with two straight titles, the national media marking our only two major sports championships with an unofficial asterisk because Michael Jordan had retired, even though he had returned before the second one. Our beloved football team left town, and our beloved baseball team was frog-marched to the American League.

What other city has suffered so?

Back in March, there was every reason to believe this Astros team could be the one to reverse the curse.

The Astros ended their final spring training camp in Kissimmee, Florida, boasting a young team loaded with talent and brimming with optimism. It seemed fortuitous when emerging star Correa hit the last home run in their spring training grounds of three decades, a towering shot to dead center, not far beneath the soaring ospreys gliding above the park.

SI was on board. The magazine had revised its timetable, proclaiming that the Astros, after their surprising 2015 season, would be champs this year, not next.

Cheryl and Kayla were feeling optimistic, though it was tinged by trepidation, which every Astros fan has learned to adopt as a coping mechanism.

They decided to attend both opening days this year: the season opener at Yankee Stadium and the home opener in their new seats. “It’s a bucket-list thing for me to go to every stadium,” Cheryl said of their trip to the Bronx. “My mom always wanted to do it, and we just couldn’t make it. That’s something that made this special. Opening day there—I can’t even tell you how amazing that was, and how cold. Ugh.”

The home opener was electric. The place was sold-out, and to Cheryl, the buzz in the stadium felt like a playoff game. “Everybody knew the talent was here,” she said. “The hope was that everybody would get it together at the same time.”

That’s exactly what they did not do. The Astros’ April was bizarre. Tyler White, Altuve, and Colby Rasmus all were named AL Players of the Week that month, but no two of them, nor any other Astro, could get hot at the same time. The starting pitching was mediocre, and the new fireballing closer that Luhnow had acquired in exchange for no fewer than five prospects over the winter—Ken “100 Miles” Giles—was awful.

As of May 1, the Astros record stood at 7-17, second-worst in the American League. “I felt that we were cursed,” Cheryl said. “That was tough. I’m not gonna lie. Part of it was ‘Here we go again.’ I tried to be positive, and I always had hope. And hello, it was April. It’s a very long season. There was so much baseball left to play.”

Indeed there was, and before long, they turned it around. From May 24 to July 24, the ’Stros were the best in baseball, racking up 37 wins against 16 losses to bring them to a 54-44 record, only two and half games behind the division-leading Texas Rangers.

It seemed as though everything was falling into place, especially since Giles had found his mojo in the bullpen, Correa and Springer had been solid, and Altuve had played otherworldly all year long. Luhnow called up third baseman Alex Bregman, the organization’s top prospect, from Fresno, and the former LSU star came inches away from a grand slam in his very first game. But then the offense began to struggle, with Bregman collecting only 2 hits in his first 35 at bats. The team would lose 16 of its next 23 games, dropping to third place in the AL West, ten and half games behind the Rangers, and to the fringe of the race for the last wild-card spot.

Yet there was still time, 41 games to be exact. The baseball season, after all, is a marathon, 162 games and six months long. The length of the season makes baseball fundamentally different from other sports. A football team, for instance, plays for three hours once a week, and devoted fans spend the other six days debating what will, or did, happen. Very little of football fandom involves actually watching the game. Baseball is the opposite. There’s barely time for punditry; whether your team won or lost that night, there is usually another game tomorrow. The joy is in the journey, the experience of watching your favorite players every day for half the year, always there in the background of our lives, until the heat of the summer fades and the season winds down and eventually, inevitably, they break your heart.

A treasured family relic is a letter my grandfather Moe Taylor wrote in June 1984 to my grandmother Susy, who was visiting England with her aunt.

Back in Texas, Moe was holding down the fort in a crowded old house on Institute Lane, a twenties-era spread that had just lost half its copper roof and a third-floor sleeping porch to Hurricane Alicia. He was a bit of a scoundrel when it came to cable TV. Moe saw no percentage in buying more than one box, not when he could rig all the TVs in our three-story house and garage apartment with clandestine wiring, and every day of every summer, each and every one of those second-hand, illicitly cabled TVs would be blaring the Astros at full volume.

Four of his daughters, three of them college-age, and two of his grandchildren were under his roof, along with a lodger or two and several dogs. In his letter, between tales of the James Thurberesque adventures of all these characters, like John Coltrane returning again and again to a riff, Moe made sure to keep Susy apprised of the Astros’ failings, inning by inning.

It’s now 9:30 and I’ve just gotten upstairs in time to watch the start of the Astros game against the Dodgers in L.A. Nolan Ryan is pitching for us tonight.

Moe had gotten the house sprayed, he wrote. Didn’t want the roaches to get a big start as summer moves in on us. Encouraging report cards from Jenny’s kids. Libby had an upcoming date with a real cute St. Thomas student from New York. And: end of first inning, Astros 2, Dodgers 2.

Moe followed with a quick update on Libby, her travels, her photography, her nannying.

(A quick third inning—still 2–2—Ryan has three strikeouts so far.)

Moe then delved into a brief account of sisterly combat over the washing machine and the general pecking order that I excise to protect the guilty and the innocent.

Jenny and the children just came into our room bug-eyed. They’ve been watching Psycho II and it’s even more frightening than Psycho. I saw it this afternoon.

(We didn’t get anything in our half of the fifth, and Ryan got one man in the Dodger half and had to leave with that damn blister problem that caused him to leave one earlier game this year. . . . [Vern] Ruhle coming in for relief.)

Ray Knight in the hospital now. They finally had to go after that kidney stone.

Ruhle got them out, so it’s on to the sixth inning.

Some political news follows. Moe was actively involved in Republican politics at the precinct level.

(Bad news in the sixth. Dodgers hit a ball between [Craig] Reynolds’ legs for an error. Then a single over Reynolds’ head. Another single Reynolds couldn’t get to. A squeeze play brought one in, and then the Astros catcher threw over the baseman’s head and two more scored on an error. So Dodgers scored three runs on one hit and our three errors. We continue to beat ourselves.)

Note: I couldn’t take it anymore, so I turned that mess off and went to sleep.

Over the decades, Moe came to take a perverse delight in the Astros’ many debacles. How could you not? As calamity followed calamity, you learned to trust your dread, and he did so over and over again, with every game that the Astros lost 2–1 while leaving fourteen men on base. “Isn’t that just typical?” he would say, shaking his white-haired head and smiling. And he passed away shortly after yet another “This kind of thing only happens to the Astros” moment.

It was 2008, and the ’Stros were still in contention when Hurricane Ike ripped through town in September, postponing a key series against the Cubs. Instead of rescheduling the games to be played in Houston after the city had recovered, Commissioner Bud Selig mandated that they be played immediately at a “neutral site.” Which just happened to be Milwaukee, the second-closest ballpark to Wrigley Field and the home of the Brewers, a team his family owned. The Astros were swept and eliminated from contention, and Moe died a few months later, his long-earned lack of faith in the Astros rewarded with no championships.

After the debacle in Milwaukee—just as Moe did during that terrible game against the Dodgers in 1984—I turned that mess off and went to sleep. For a period of years.

In late August, I met Cheryl and Kayla at Minute Maid to watch the Astros play the Oakland A’s. I hadn’t been to the ballpark in years, and walking in, I suddenly felt shaken from my slumber. Everything seemed bolder, brighter, like someone had Technicolored the Astros. Gone were the bland, muted shades favored by former owner Drayton McLane. Crane, the new owner, had restored orange to the team’s color scheme, which, along with the green seats, gave the stadium the look of a citrus grove promised by its name.

And once more the Astros were in contention. Their record stood at 69-62 after a hot streak that saw them win 12 times in 20 outings and creep close to a playoff spot. Cheryl and Kayla arrived unusually late—Kayla had had a bear of a Spanish homework assignment that night—and by the time they got there, in the third inning, the Astros had taken the lead on two great plays from fresh-off-the-DL and newly mulleted Rasmus, who both threw out a guy at the plate from left field and later launched a homer to right.

As they always do, Cheryl and Kayla took their seats in section 131 decked out head to foot in Astros attire, including accessories; on this night, Kayla wore a blue pullover, her mother a blue-and-orange hoodie. The night before, they had worn custom-made orange jerseys, and in place of the name on the back, Kayla’s read “Fans” and Cheryl’s read “Forever.” (Kayla sported number 4 for Springer, her mother number 19 for Doran.) They never wear the same ensembles twice in a row. “People ask me if I have a whole Astros section in my closet,” Cheryl said and left that issue a mystery. She did admit that she would wear the same Astros necklace and bracelet to the next game if the Astros won, and that Kayla would wear the same jersey over her T-shirt under the same circumstances. “I have three pairs of Astros shoes,” Cheryl said. “And Kayla has some too, and we will keep wearing them until the Astros lose.”

Cheryl, an attorney, also has an Astros shrine, which she keeps on her desk and which has, until recently, followed her from law job to law job. Its highlight is a piece of vintage Astros folk art: a lamp hand-crafted by former Astros bullpen catcher Stretch Suba. The shaft is a broken piece of a Doran bat, and the shade is an Astros batting helmet. She has a certificate of authenticity and everything.

Then there are the signs they bring to the games. They’ve made sparkly signs for nearly every Astro except Altuve. On the back of one of them, Kayla has scrawled out notes of a few plays her mom has missed at various games while on the concourse: notations like “Nice play by Marwin on a ground ball,” “Gomez couldn’t get to a fly ball in center.”

Why the exception for Altuve, the team’s best player? Cheryl explained that fellow fanatics who sit on the third-base side have anointed themselves his personal cheering section, with four of them holding up a sign for each letter of his first name every time he steps to the plate or makes a nice play in the field. “We decided that he belonged to them,” Cheryl told me. And by “we,” she means the season-ticket holders in section 131, who have become so tight-knit they are beginning to bandy about a group name for themselves.

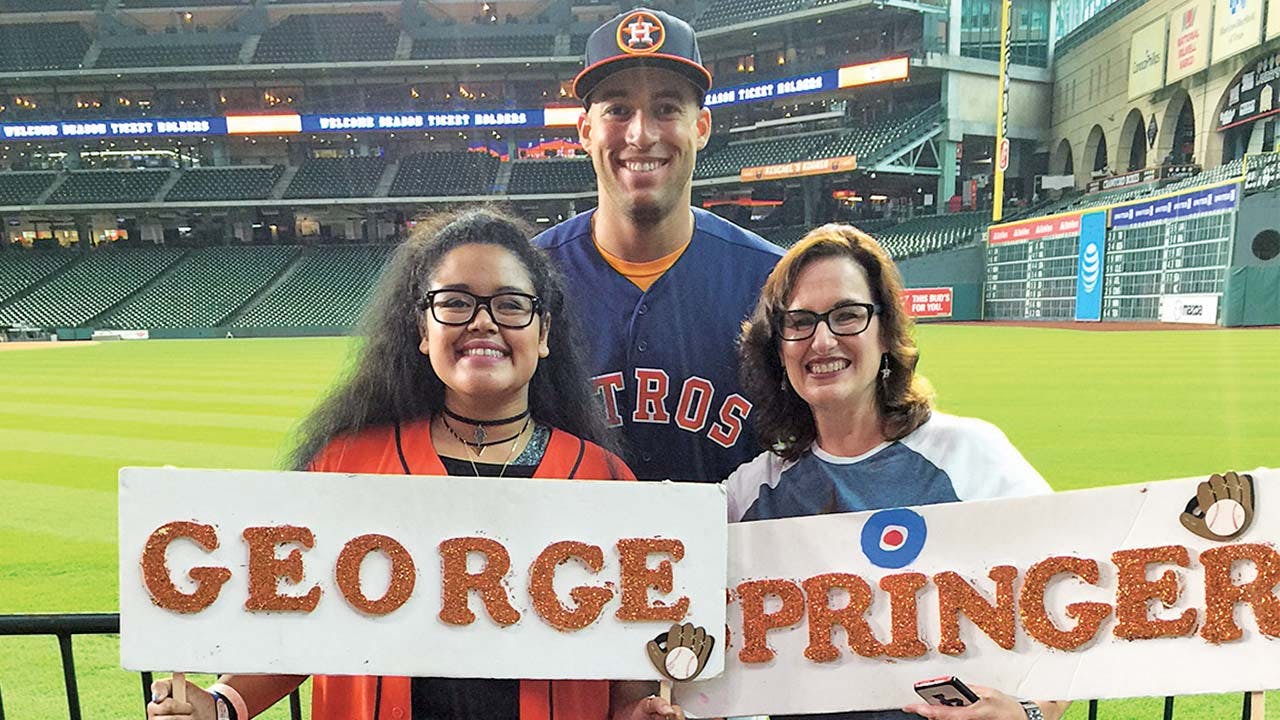

Meanwhile, the A’s were due up, and for the first time since the Clarks’ arrival, Springer trotted out to right field. “Watch,” Cheryl said, “we’re gonna wave our signs, and he is gonna wave to us.”

Springer loped out to his position. Mother and daughter waved their hand-crafted signs, sparkly as the prize wheel on The Price Is Right, Cheryl’s reading “George” and Kayla’s reading “Springer,” each with a little baseball glove glued on it. Springer appeared to ignore them, first keeping his eyes straight ahead and then glancing toward the ball boy with whom he was about to play soft-toss between innings. But just when you thought he wouldn’t, he smiled and waved at his biggest fans. The Clark women turned and grinned at me.

Not long after that, Springer made a nifty running catch right in front of us, in foul territory, so close you could hear his spikes thudding into the turf, his uniform already stained from chest to stirrups with dirt from a slide earlier in the game, looking much like Doran once did.

By the seventh-inning stretch, when “Deep in the Heart of Texas” played, the Astros led, 3–0. Kayla and Cheryl stood and sang and clap-clap-clap-clapped. And they smiled, looked into each other’s eyes, and hugged enthusiastically when the second verse rolled around.

The sage in bloom is like perfume

Deep in the heart of Texas.

Reminds me of the one I love

Deep in the heart of Texas.

The A’s scored a run in the eighth inning, but Giles, now back in the closer’s role that everyone had envisioned for him when the season began, pitched a perfect ninth inning, and the Astros won, 3–1. They did so again the next day, completing a three-game sweep of Oakland.

Then came a weekend series against the Rangers in Arlington, the Astros’ house of horrors. Cheryl and Kayla and a bevy of fans drove up to North Texas to attend all three games, but predictably, the Astros managed to win only one of them, continuing their futility against their in-state and division rivals. In the following weeks, the team’s playoff prospects dimmed even more. The Astros won just enough games to remain in contention, but not enough to overtake the clubs ahead of them. As the team’s outlook faded, Cheryl was sanguine. “Lots of people hoped this might be the year, but a lot of people recognized that it might not,” she said. “Our future is very bright. We are not going back to 2013.”

And there was still plenty of joy along the way. In early September, Cheryl emailed that she was planning a trip to Seattle to watch the Astros play the Mariners. “[Kayla] really wanted to be at the game on Springer’s birthday which is September 19, the problem being they are going to be in Oakland and it’s a Monday,” she wrote. “So I am surprising her with a trip to Seattle this weekend to watch them play Friday and Saturday. That way she can wish George an early birthday (I’m working on the sign right now).” The cover story was a business trip, but when they got to the airport, Cheryl would surprise Kayla—their version of the classic surprise trip to Disney World, except, for a die-hard Astros fan, even better.

While at Safeco Field, Cheryl posted on Facebook: “I have a sippy cup of wine, chocolate covered strawberries on a stick, it’s 68 degrees and I’m watching the Stros in an open air stadium with my girl—I think I may be in Heaven.” And Springer signed the “Happy Early B-Day George” signs they had brought all the way from Houston.

The team would take two of three in Seattle and win on Springer’s birthday, in Oakland, but it wasn’t enough. The Astros finished 84-78, just outside a playoff spot. Despite all the promise, it would once again be, wait till next year.

But the Clark ladies were undaunted. “It has been sooooo worth it!” Cheryl told me. “I don’t regret a single penny. I want them to go to the postseason, but it’s the game. It’s being there: the atmosphere, the people, the camaraderie. You don’t have to explain why you have orange sparkle signs.”

After all, back when she was going with her mom, back in the late eighties, a decade away from the Astros’ next sustained run of success, it was more about the experience than the wins. “They did nothing in those years,” she says. “And we had the same thing in the stands: so much fun.

“That’s what makes sports so fun. It’s the emotional roller coaster ride. If you don’t have that, it’s boring. If you always win, it’s boring.”

Which is a good point. Who really enjoys being a Yankees fan?

“Right!” Cheryl said. But it would be nice to win. Once.

Of course, winning a World Series would make Cheryl and Kayla happy but only marginally more so than they already are every night at the ballpark together. “Everything else goes away,” Cheryl told me, sitting in section 131 at the A’s game. “This is our happy place.”

- More About:

- Sports

- Longreads

- Houston Astros

- Houston