When book critics gather around the campfire to list the names of the best Texas authors of contemporary Westerns, one name jumps out among the usual suspects of Cormac McCarthy, Larry McMurty, and Elmer Kelton: James Carlos Blake. Fourteen years ago we even went so far so to dub Blake “the next Cormac McCarthy,” based largely on his 1997 novel In the Rogue Blood, a dark, brooding book about brothers fighting on opposing sides of the Mexican-American War that was likened to Blood Meridian and went on to win a Los Angeles Times Book Prize.

He’s tried to live down the accolade ever since. “That was embarrassing as hell,” said Blake by phone from his home outside of Tucson. “No serious writer likes to be compared, but it’s nice to be compared to the best. I hope most people are past that.”

Like McCarthy, Blake writes novels dominated by male protagonists who exorcise their demons through vivid and visceral acts of violence. But unlike McCarthy, most of Blake’s fiction has been fashioned around colorful figures drawn from history, such as The Pistoleer, about the legendary outlaw John Wesley Hardin, or Wildwood Boys, about the Confederate guerrilla leader William T. “Bloody Bill” Anderson.

“I’m attracted to and write about people who are very resentful of submitting themselves to authority that they don’t think is warranted,” said Blake.

And despite the McCarthy comparison, Blake has never enjoyed particularly strong sales. His work, though usually published by major New York houses, has remained a niche interest, exclusive to fans of the hardboiled, historical Western genre.

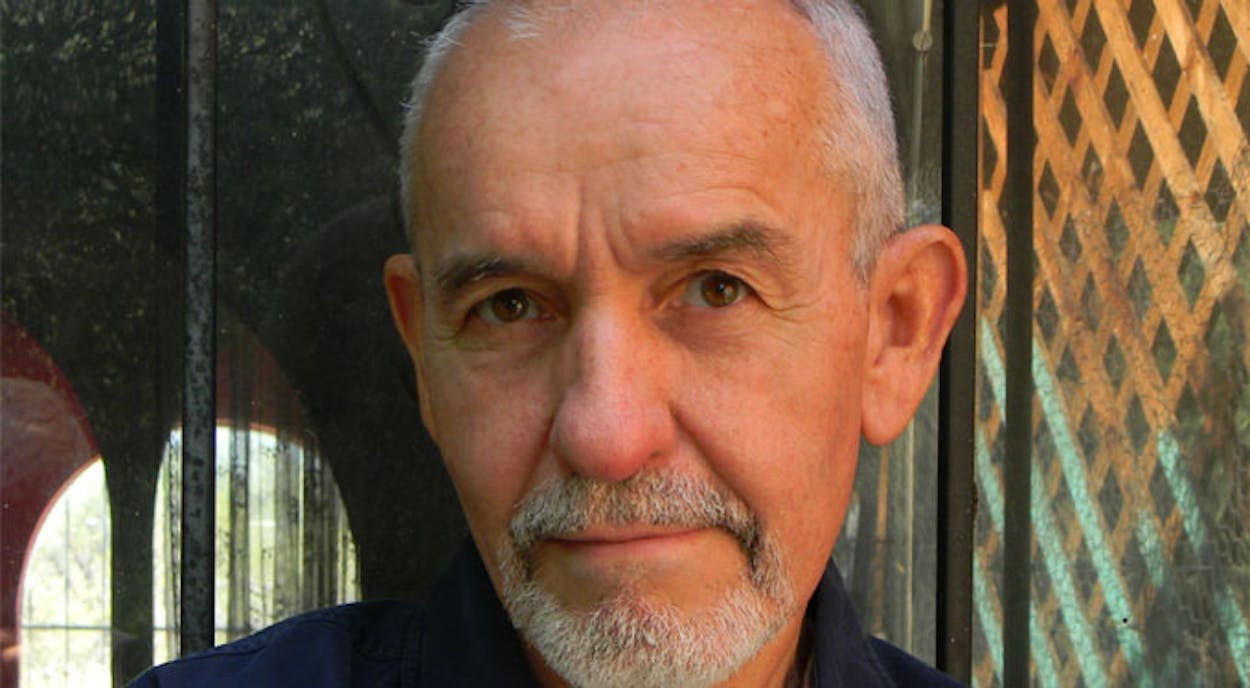

A self-described “hotlander,” Blake was born in Mexico and raised in Brownsville. Now 66, he says being bicultural was a gift, since it provided him with a “warehouse of voices” to draw upon as a writer. It also gave him one of his primary obsessions: the border.

“The border, as I see it, is a sovereign culture. There is not much there, yet there are a lot of people who live there and they see themselves as borderlanders. My father always saw himself as one of those guys.”

Blake’s most recent work was inspired by his father’s colorful family history. His 2012 novel, Country of the Bad Wolfes (Cinco Puntos Press), introduced the epic history of the fictional Wolfe family, a Mexican-American clan with a penchant for troublemaking and crime. Well, somewhat fictional: The founder of the Mexican wing of the Wolfe family is the nineteenth-century British pirate Roger Blake Wolfe, who early in the book is executed in Veracruz; Blake’s own great-great-great-grandfather Robert Blake, was also a British pirate who was executed in Veracruz.

A reliably prolific writer who published a book nearly every year from 1995 to 2005, Blake went silent for seven years before Country of the Bad Wolfes was published. He explained that in 2005 he took a year-long break to road trip across the US and recharge. Then, over the course of two years he took several lengthy trips to Mexico to research his family history and the cartels.

“I talked to a great many people who are very knowledgeable about the major criminal organizations in Mexico, including some of my many relatives,” he said. “Most of my family is from Mexico City and, like the Wolfes, my father’s brother was an import/exporter. The family down there has always had rumors about it. My uncle was one of those people whose sons still kissed his hands. My dad was always glad he didn’t stay there because of the sort of life he might have led.”

Blake then took another three years to write the book, and it spent another year on its way to publication.

Now, with this June follow-up, The Rules of Wolfe (Mysterious Press), he’s back to his regular clip. The new novel jumps ahead a century or so to 2004, when nineteen-year-old Eddie Gato Wolfe, working security at one of the pleasure ranches of a drug cartel, seduces (and is seduced by) a kidnapped Mexican beauty, kills her captor, and flees for the border. The novel then unfolds like one long chase scene, alternating between Eddie and the two sides closing in on him: the cartel, intent on revenge, and his Wolfe cousins who are intent on saving him.

Now, with this June follow-up, The Rules of Wolfe (Mysterious Press), he’s back to his regular clip. The new novel jumps ahead a century or so to 2004, when nineteen-year-old Eddie Gato Wolfe, working security at one of the pleasure ranches of a drug cartel, seduces (and is seduced by) a kidnapped Mexican beauty, kills her captor, and flees for the border. The novel then unfolds like one long chase scene, alternating between Eddie and the two sides closing in on him: the cartel, intent on revenge, and his Wolfe cousins who are intent on saving him.

One thing that has always distinguished Blake is that despite the violent nature of his protagonists, they are nearly always thinkers. The cousins, for example, may be gun thugs, but both of them were college English majors—one specializing in Hemingway, the other in neoclassical poetry, whose thesis, he brags, was titled “The Role of the Interlocutor in Pope’s Horatian Satires.” As unlikely as this may seem, Blake said it is deliberate. “All my characters are intelligent. I’ve never been interested in alcoholics, druggies or crazy people, because they are not exercising free will.”

Blake said he has conceived a long series of Wolfe books, which should provide enough material to occupy him for the rest his writing life. And while he may have broadened his scope beyond the Western to take on contemporary story lines, Blake promised one thing will never change.

“Sex and violence will still predominate, he said. “They are the two great engines of the world.”

- More About:

- Books

- Cormac McCarthy