On the second Saturday of fall in Austin, college football was on the TV, an Astros double-header played on the radio, and the smell of barbecue traveled on a now slightly cooler wind. And, Austin being Austin, streams of people made their way to a concert. But for the roughly 55,000 people who gathered on the grassy slopes of Auditorium Shores—Town Lake gently rippling behind it—Saturday’s highlight wasn’t Willie Nelson, the closing musical act. They came to see Beto O’Rourke.

Jalan Beck wasn’t yet born the last time a Texas Democrat won a statewide election. But the nineteen-year-old arrived early to the Turn Out for Texas rally, two friends and a positive outlook in tow. “I feel like everyone wants a change,” she said. “And we can accomplish that if we work hard enough and encourage people to vote. We’re at the beginning of our adulthood, and we’re seeing how things affect us and other people too. Beto is someone who represents inclusiveness for everyone.”

“I mean, dude, he skateboards around Whataburger,” her friend Sydney Bucek, 20, interjected.

Just then, a woman walked by toting a sign that read, “He’s working for the clampdown,” repeating a phrase O’Rourke directed at Cruz during their first debate. It marked, to the best of my knowledge, the first time a song by the Clash was referenced by a Texas politician.

Despite O’Rourke’s punk rock background, the crowd sprawled out on blankets and sipping beers from camp chairs looked more like the kind you’d find settling in at Willie’s Picnic than gearing up for Warped Tour’s mosh pits. There was a surprising amount of Aggie maroon among the burnt orange ball caps, and I saw just as many potbellied dads in Magellan fishing shirts as I did heavily-tatted hipsters. There were a surprising number of families. And though Cruz recently claimed that his opponent would ban barbecue if elected, there was a long line at the Salt Lick food trailer. (I didn’t spy anyone chowing down on tofu.)

Sprinkled among the attendees were 250 voting registrars sporting high-vis vests and clipboards. A recent Washington Post study placed Texas last in voter turnout for the 2014 midterm election, a ranking that people like Von Niezgoda are hoping to change this cycle. When I bumped into Niezgoda, who had driven from Houston for the rally, he was reclining on the grass wearing a Hawaiian shirt and well-traveled cowboy boots, looking as if he’d be perfectly at home sipping a piña colada at Jimmy Buffett’s Margaritaville. “I’m an active Beto volunteer in Houston,” the 64-year-old told me. “We’re going door-to-door and registering voters. All those people out there who are frustrated with what’s going on, that’s who we’re trying to galvanize. Right now [the race is] close, and just like Trump surprised Hillary in a lot of swing states, we’re hoping Beto can surprise Cruz.”

Niezgoda, who served as a precinct captain during Obama’s presidential campaigns, stressed the importance of this election for his party. “We feel the House is up for grabs, and one-third of the senators are up for re-election in November. 2020 will sneak up on us before we know it. We don’t view this as a typical midterm—this is a critical turning point.”

There’s been plenty of that kind of enthusiastic tactical talk at O’Rourke’s appearances in all 254 of Texas’s counties over the past year. But this particular event wasn’t strictly business. Around eight that evening, Joe Ely, the first of the musical acts, took the stage. The Lubbock native has long been one of the state’s most-heralded country songwriters (fittingly, he has also toured with the Clash). While Ely played “All Just to Get to You,” a boy scrambled up an oak tree to watch the show from one of its limbs. What had been a dreary rainy day turned into a fine sunset as rays finally broke through the slate of grey clouds to throw pinks and yellows across the glass-paneled skyscrapers of downtown Austin. Austin-based singer-songwriter Carrie Rodriguez, up after Ely, quieted the crowd with her fiddle, singing in Spanish and English on “Llano Estacado.”

Backstage, a line of VIPs waited for an opportunity to snap a selfie with O’Rourke, who was fresh from delivering the keynote at the Texas Tribune Festival. The six-foot-four candidate often had to stoop to wrap his arm around the shoulder of whoever posed beside him. Using a tall pecan tree as the backdrop, he seemed genuinely thrilled to be posing for pictures with his supporters. One woman was sporting custom-made cowboy boots with the candidate’s likeness stitched into the shanks, with “Beto” running along both sides. At one point, O’Rourke called over his wife, Amy, to take a picture with a young man they both knew from El Paso. The vibe was somewhere between a family reunion and a celebrity autograph session. O’Rourke somewhat famously drips with perspiration while making his impassioned speeches, but, at least for the moment, his light blue collared shirt was sweat free.

Once he had gotten to everyone in line, O’Rourke joined Central Texas Congressman Lloyd Doggett, California Representative Adam Schiff, and Colorado Representative Diane DeGette in the VIP area. I went to watch Tameca Jones, another Austin-based artist, who offered soulful, grooving covers of “Bennie and the Jets” and “With a Little Help From My Friends.” While watching Jones perform, a friend in the VIP area texted me: “A bartender just notified the campaign that she’d seen a couple of people jump the fence to get back here and meet Beto. I looked up, and at the of the row of Porta Potties, there were all these hands raised over the fencing holding cell phones.” We were reaching peak Betomania.

Before Leon Bridges began his set, I spoke with Cathy Redson, a former educator who was there with friends from across the state, all of whom were brandishing handmade Beto signs. “I recently ran into a longstanding Republican friend of mine,” she told me. “He and his wife had a watch party [for the Cruz and O’Rourke debate] and had invited thirty of their best Republican friends. He was disappointed when Cruz couldn’t take the opportunity to say something nice and had to insult Beto. He was embarrassed by Cruz’s performance that night.” That, she said, had been the last straw for her conservative friend. “He switched over to support the Beto campaign. And he’s working hard to convince other Republicans to do the same. And he’s not moderate. He’s not in the middle.”

Though I tried throughout the night to find a voter who had come to the rally undecided (or, more unlikely, decidedly fixed against O’Rourke), I failed to find anyone. A friend who had arrived before me said that she had seen a few protestors who had been asked to leave, and did so peacefully. But by the time I got there around six in the evening, crimson with shame after riding one of those stupid electric scooters for the first time, there were no signs of any vocal dissenters.

The filler music between sets turned abruptly from Marty Robbins’s “El Paso” to the Clash’s “Clampdown.” As the song began to enter its chorus, the emcee introduced “the pride of Fort Worth” Leon Bridges. Wearing a Texas Rangers jersey and a knit beanie, Bridges took the stage and began to move through a mashup of songs from his debut album Coming Home and this year’s Good Thing. At one point, the singer abandoned the microphone to do an extended dance at the front of the stage. After a lively set, Bridges ended on a gospel note, picking up the electric guitar for the first time to play a sparse version of his song “River.” “Much love to Beto,” he said in parting.

Austin City Councilman Greg Casar came out to hype the crowd for the main event, his voice cracking occasionally as he whipped up the crowd up for the main speaker. “There’s one more brave guy whose back we have to have,” he said. “A fellow Texan, a progressive champion, one of our own. His name is Beto O’Rourke.”

It was time for the main event. O’Rouke came bounding onstage to chants of “Beh-Toe! Beh-Toe!” as a sea of black-and-white signs shimmered in the stage lights. “Good to see all of you,” O’Rourke said, grinning. “Even those of you I cannot see. Thank you for being here. Thank you for being with us. Thank you for being for Texas and for this country we love so much.”

For fifteen minutes, the candidate weaved his way through a stream of different policy positions, somehow seamlessly moving from immigration to healthcare for special needs children to his support for farmers and ranchers. He briefly switched to Spanish, then continued in English, when he spoke of his dedication to public education. He talked about veterans and bringing home troops from winless wars, America’s swollen prison population, and his desire to end the prohibition of marijuana and tackle the opioid crisis. He ticked through several other Democratic priorities, including gay rights and climate change, and turned to a few Texas-specific problems, such as the high maternal mortality rate and the alarming issues facing Child Protective Services.

“I don’t care about our differences,” he said. “If you’re a Republican, you are in the right place. If you’re a Democrat, you are in the right place. If you’re an independent, you are in the right place.” By this time, pools of sweat had begun to darken his blue shirt. “Whoever you pray to, whether you pray at all, whoever you love, however many generations you’ve been in this country or whether you just got here yesterday, we’re all in the same boat, we’re all human beings, and we’re going to start treating one another that way.”

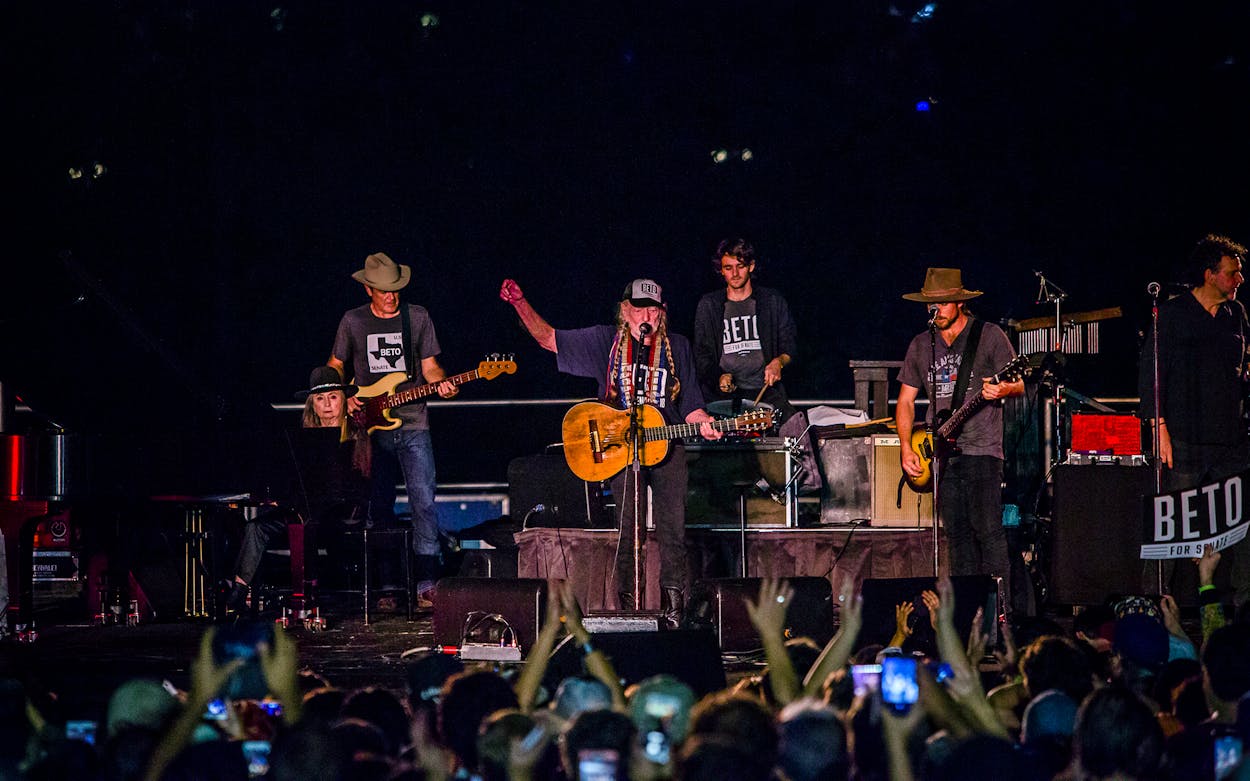

O’Rourke left the stage to the same chant that had brought him out, while Willie Nelson’s “Living in the Promiseland” came on over the PA. Less than five minutes after O’Rourke exited, Nelson came on, accompanied by sister Bobbie, drummer Paul English, bassist Kevin Smith, harmonica player Mickey Raphael, and Willie’s sons, Micah and Lukas. Just as has been the tradition for decades, the patron pigtailed saint of Texas strummed a few downstrokes on his guitar, Trigger, and launched into “Whiskey River.”

Decked out in a large black Beto tee and a Beto ballcap, Nelson didn’t spend time politically proselytizing between songs. He yelled, “All right, Beto!” and went straight into “Still is Still Moving to Me” which he followed with Bobbie’s piano-driven instrumental “Down Yonder.” After tossing his cap out into the crowd and replacing it with his trademark red bandana, Nelson and his band switched up the set with a cover of Stevie Ray Vaughan’s “Texas Flood” led by Lukas. As Nelson’s eldest son began shredding his guitar solo, a woman next to me sighed, “He’s very attractive.” Her friend emphatically agreed.

It was sometime during “Mammas Don’t Let Your Babies Grow Up to Be Cowboys” that I felt a sharp poke in my ribs. I spun around to find a short old man, his eyes huge and wild behind a thick pair of Coke-bottle glasses, chuckling as he gave me one more jab with his wooden cane. “God bless America!” he hollered. “And God bless Willie Nelson!” I didn’t appreciate the poke, but I couldn’t disagree with the sentiment.

O’Rourke came back out and joined the band for “On the Road Again,” but the highlight of the set was hearing a new Willie tune. On “Vote ‘Em Out,” Nelson sang, “The biggest gun we’ve got is called the ballot box / If you don’t like who’s in there, vote ’em out.”

I heard a couple of people still singing the refrain on my walk back across the First Street bridge. It’s hard to know for sure what will happen in November, and Nelson doesn’t have the best track record for backing candidates. But there does seem to be an undeniable energy around O’Rourke’s campaign, anchored in his willingness to reach across an ever-widening divide.

As I walked, my thoughts turned to the first person I had spoken to at the event, a man named Servando Rodriguez. He drove with his wife and sister-in-law from San Antonio earlier that day. At 61, this event marked his first political rally. Sure, he was excited to see Nelson, but he told me that he’d come because he recognized something in O’Rourke that inspired him. “I’m old enough to remember when [John F.] Kennedy was killed,” he told me. “In Laredo, where I’m originally from, everybody was crying, because Kennedy was trying to help the Hispanic people. I can see Beto trying to do the same, but it’s not just Hispanics. He wants to help everybody, because we’re all humans. That’s the reason I’m here: to support Beto.”

- More About:

- Politics & Policy

- Music

- Willie Nelson

- Beto O'Rourke