The last text Bob “Daddy-O” Wade sent me was a predictably silly, politically incorrect, groan-worthy video meme, which is to say quintessential Daddy-O. Bob loved playing the role of a naughty imp. He’d sent me dozens of similar texts over the years, and I expected to get more in the months and years to come. But four days later, just past midnight on Christmas Eve 2019, he died at his house on Mount Bonnell in Austin’s Northwest Hills after dealing with heart issues for several months. He was 76, but his abrupt departure left me stunned. Bob projected energy and charisma, even in his waning years. It’s hard to fathom a world without the Daddy-O.

Bob was an accomplished artist, best known for his outsize sculptures of cowboy boots and an iguana and his series of paintings of cowgirls based on postcards from the early 1900s. He had earned a master’s degree in painting from UC-Berkeley and could quote Clement Greenberg and other important art scholars. His work has been exhibited at the Whitney and other highbrow museums, even though, as art critic Dave Hickey observed, the biggest influence on Daddy-O’s work seemed to be the homecoming float. Bob’s sculptures and paintings are taken seriously by his peers, yet they are also as much fun as any parade. His fans include legions who have never read a word of art criticism or set foot in a gallery. That was fine by Bob. He told me once that he preferred the ambience of a rodeo to the stuffy New York City art world. There’s no room for vagary or self-reflection in the rodeo arena. You either stay on the bull for eight seconds or you don’t. Bob liked that. He also liked that rodeo cowboys roar into town, ride and rope, then hit the highway for the next show. Bob said he only looked forward, not backward.

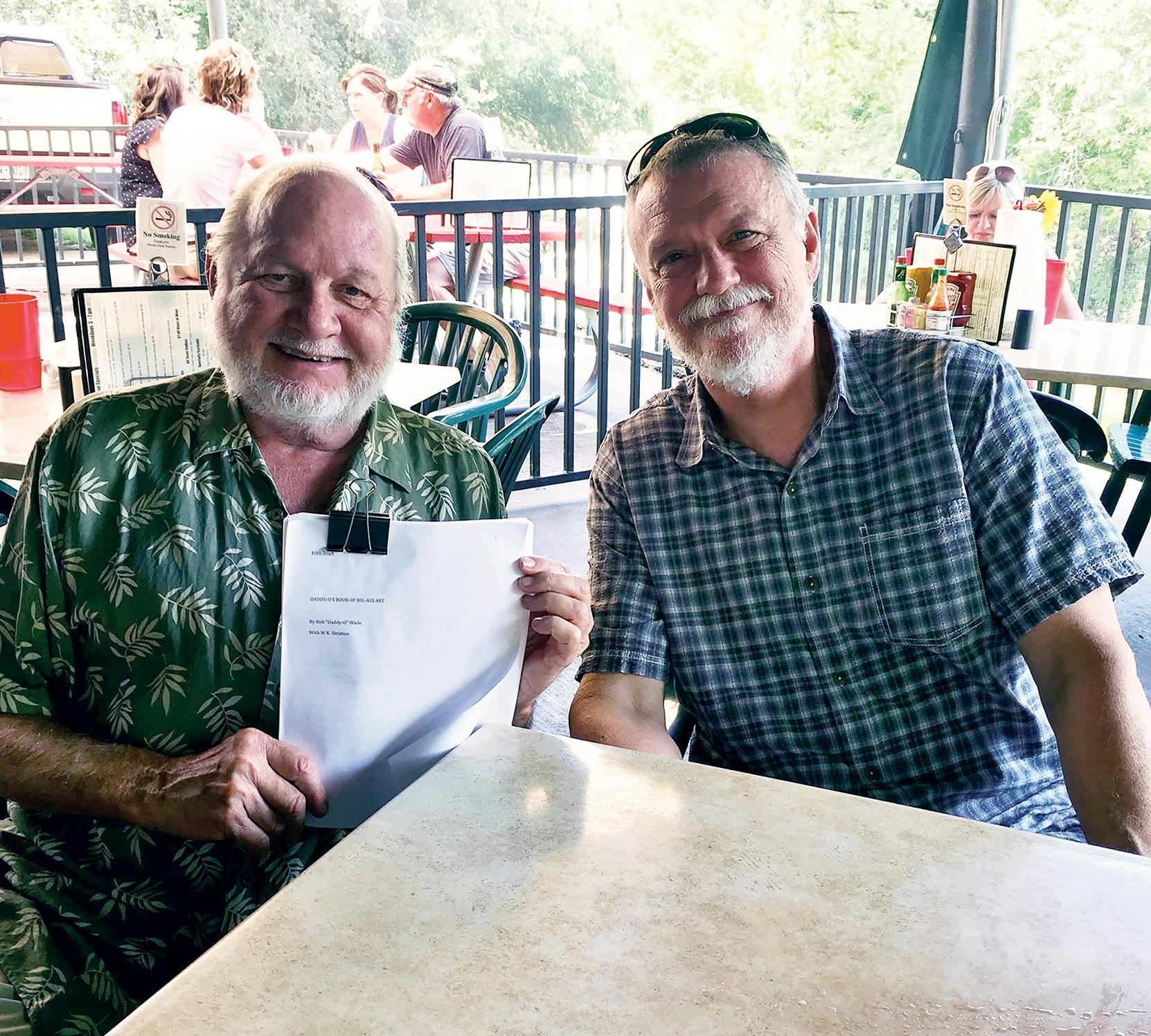

It’s ironic, then, that Bob and I spent much time together poking around the past during the last four years. He enlisted me to help him put together Daddy-O’s Book of Big-Ass Art, which will be published by Texas A&M University Press this fall. The book is a compendium of photographs of his work and essays, both new and previously published, about his life and career. After I signed on, Bob became a constant presence in my life. As we worked together, I discovered that the past was very much alive for Bob. He had great recall of people, places, and events.

Bob was born in Austin but his father managed hotels, so the family moved around. Young Bob soaked in the sights every place he lived. The elder Wade was running the Hotel Paisano in Marfa when director George Stevens and company invaded town to film Giant, an epic movie chock-full of Texas iconography, much as Daddy-O’s art would be. But more important to his future as an artist was his time in front of the black-and-white TV watching the endless procession of Westerns that aired in the 1950s. He loved what he saw. Those images of Marshal Dillon and Paladin and the others became the creative foundation for his art.

Throughout his life, Bob proudly claimed the King of the Cowboys, Roy Rogers, as his second cousin. Forty years ago Bob wore jeans, boots, and Western hats; a tethered longhorn grazed on his Northwest Hills lawn on at least one occasion. But Bob was no cowboy. “I never owned a horse,” he told me over lunch at Austin’s Shoal Creek Saloon, his primary hangout in his last years. “I never really wanted to own one.” But he saw endless artistic possibilities with the iconography of the West and Texas in particular, especially when rendered with late-20th and early-21st century perspectives.

His range extended well beyond cowboys and cowgirls, to lizards, frogs, fish, and other critters, as well as musical instruments, football helmets, travel trailers, and Mexican revolutionaries. Much of this related to his experiences as a teenager in El Paso, where his peripatetic family eventually landed. Like his contemporaries Luis A. Jiménez Jr. and Boyd Elder, he thrived in the border environment. Merchants in Ciudad Juárez hawked inexpensive souvenirs to tourists who’d come across the river. Their wares included everything from taxidermic iguanas to paintings on black velvet. Bob became a collector of such kitsch. Eventually it would inspire some of his best-known work.

Pachuco culture was in full flower in El Paso, and Bob picked up on its vibes. He immersed himself in the world of hot rods, which were a big thing in Chuco Town at the time. He also adopted a sort of la frontera of jive when he spoke, which never completely went away. Bob arrived at the University of Texas in Austin in 1961 as a border hepcat driving a ten-year-old, customized, tiara-gold Ford Crown Victoria. His Kappa Sigma fraternity brothers, thinking he seemed like a refugee from West Side Story, gave him the nickname Daddy-O. It stuck for life.

Bob told me that few understood that he was a performance artist. He explained that he’d take on the persona of the stereotypical smooth-talking Texas wheeler-dealer whenever he began an art project. He’d barter with Western-wear storeowners, ranchers, or farmers to get the materials he needed for art installations. He’d enlist the aid of fellow artists, students, welders, and mechanics to help him create his gigantic sculptures. The wheeler-dealer was great at self-promotion and seemed to know just about everybody. I came to think of that persona as “the Daddy-O.”

“Bob,” on the other hand, was the talent who dreamed up so many compelling pieces of art. It was Daddy-O who cavorted with his frat brothers in Nuevo Laredo’s Boys Town. But it was Bob who studied, while at UT in the early 1960s, under William Lester, Everett Spruce, and Charles Umlauf. It was Bob, the graduate student at Berkeley, who was inspired by the Bay Area’s Peter Selz and the funk art movement he advanced. It was Bob who spoke, in the words of cultural historian Jason Mellard, “the language of 1960s pop art, of Andy Warhol, Roy Lichtenstein, and fellow Texan Robert Rauschenberg. He [swam] in some of the same waters as the later masters of the postmodern like Jeff Koons.”

Bob knew his stuff for sure. I came into possession of a one-off lithograph by the Lakota painter Paul Owns the Saber, whose work is in the Smithsonian. At lunch one day, I showed it to Bob, who gave me a quick lecture about the mistakes Owns the Saber had made in terms of traditional lithography. But then he spoke admiringly of the intricacy of the pen strokes and the composition of the picture. “This is a really nice piece,” he said. Another time Bob and I attended the opening of an exhibit of paintings by my songwriter friend Tom Russell at Austin’s Yard Dog Gallery. A large canvas depicting Sitting Bull drew Bob’s attention. “Tom put a lot of work into this,” Bob said as he pointed out the dozens of white figures representing Sitting Bull’s vision, which I’d failed to notice.

Bob never subscribed to the concept, popularized by architect Ludwig Mies Van Der Rohe, that less is more. Bob believed that more is more, bigger is better. And so he gave us the world’s tallest cowboy boots (standing 40 feet), outside North Star Mall in San Antonio; the world’s longest longhorns (25 feet), at the UT Alumni Center in Austin; and the world’s biggest saxophone (70 feet), now at the Orange Show. I first became aware of Bob and his work when he created the mother of all installation art in 1976 as part of the American Bicentennial celebration. It was a map of the U.S. situated near the intersection of the LBJ Freeway and Inwood Road in Dallas. The size of a football field, the map was built of concrete, plywood, and earth and featured miniature skyscrapers, oil wells, billboards, and water-filled replicas of the Mississippi River and the Great Lakes. It included more than 300 lights to make it visible from planes departing from DFW International Airport, then just two years old. It made Daddy-O famous. I read about it in that indispensable guide to high culture, People magazine.

In that same bicentennial year, the Lone Star Café opened at the corner of Fifth Avenue and 13th Street in New York City. It was the heyday of Texas chic, and the Lone Star became its epicenter. Willie Nelson, Doug Sahm, Kinky Friedman, and Jerry Jeff Walker were among the stars who performed there before an audience that included expatriate Texans, politicians, journalists, actors, would-be hipsters, models, and media moguls. Billy Joe Shaver’s lyrics “Too much ain’t enough” were emblazoned across the front of the two-story café. Bob’s massive iguana sculpture, Iggy, wound up perched on the roof. Daddy-O made the scene at the Lone Star to rub shoulders with the famous and infamous, and his own fame grew when area business owners sued to have Iggy removed, claiming it could be classified as a sign that violated zoning restrictions. The Lone Star’s proprietors responded that the iguana was not a sign but art. The suit received a great deal of media coverage, with Bob prominently mentioned. In the end, art won. And Bob became so widely known that he was able to quit his teaching gig at the University of North Texas and survive off his paintings and sculptures for the next 43 years.

Looking back, I believe that Bob was feeling his own mortality when we started work on his book four years ago. He approached the project with urgency. He told me on several occasions that he wanted to get it done as a legacy for his children. Time was growing short. More and more often, he and Lisa were traveling to attend the funerals of friends. In 2017, the playwright and actor Sam Shepard died. When Bob and Lisa lived in Santa Fe in the 1980s, he and Shepard hung out together, often at the Dragon Room bar at the Pink Adobe Restaurant. Those were riotous, tequila-fueled nights, sometimes ending when Shepard’s longtime romantic partner, actress Jessica Lange, showed up to fetch Sam home. Bob turned melancholy as he told me about those adventures. Even more troubling to Bob was the sudden death last June in Austin of Bill Wittliff, the publisher, screenwriter, and producer whom Bob had known since they were Kappa Sig fraternity brothers.

Bob was more than a dozen years my senior, but we became close friends over the last few years. One of his last works was a painting of legendary cowgirl Lucille Mulhall, which he gave to me for my help with his final book. Nothing I own means more to me.

W.K. Stratton is the author of the Los Angeles Times best seller The Wild Bunch: Sam Peckinpah, a Revolution in Hollywood, and the Making of a Legendary Film and other books. He is a fellow of the Texas Institute of Letters.

- More About:

- Art

- Obituaries