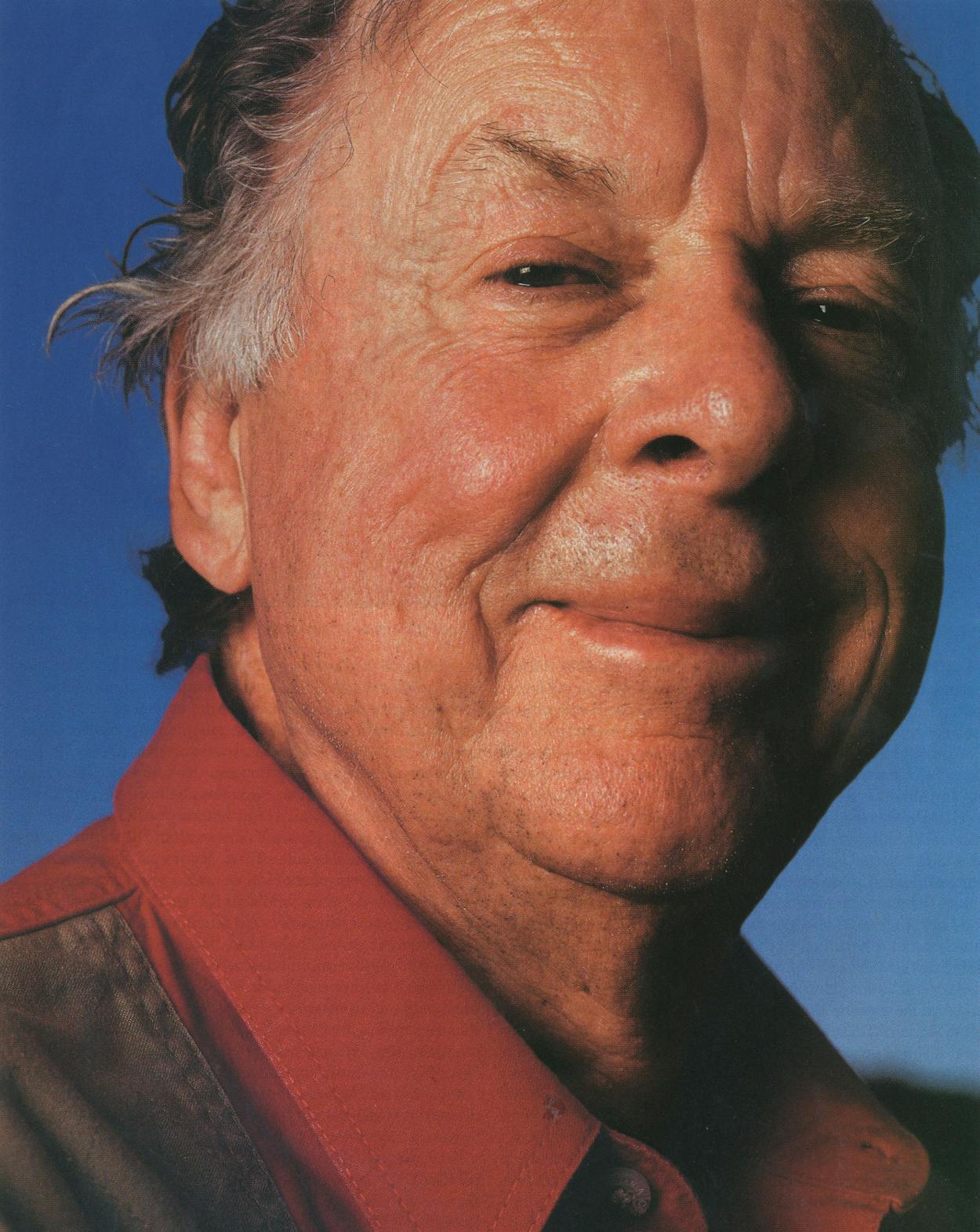

“Look! Look down there!” Boone Pickens leans across the narrow aisle, pointing toward a window of his corporate jet as it banks over the rolling plains of the Panhandle on its final approach to Pampa. “There’s where the water fields will be,” he says, motioning beyond the wing. “And that’s where my place is.” He moves his finger ever so slightly to the right to identify the Mesa Vista Ranch.

That Pickens sees water, and not some traditionally exploitable mineral like oil or manganese, on those dry plains speaks volumes about what sort of havoc a booming population is wreaking in the state of Texas. He has what he says is a simple plan: He’s going to pump the water that lies under the more than 150,000 acres of land he either owns or controls in Roberts County, seventy miles northeast of Amarillo. And then he’s going to sell it to cities like San Antonio and El Paso that are running out of water. The water lies several hundred feet below the surface. It is part of the Ogallala Aquifer, a vast underground reservoir that stretches from the High Plains of Texas all the way to the Dakotas. The Ogallala is the largest single groundwater source in the United States.

The reason that the former oil tycoon and corporate raider is able to treat this water like a marketable commodity—just like oil and natural gas—is because Texas law says he can. Though surface water belongs to the state, a landowner can pump whatever water he finds below the land. It’s called the rule of capture. He can pump as much as he wishes and sell it to whoever wants it, wherever they are, no matter if he dries up his own water and his neighbors’ water along with it. And that’s the problem. The more Pickens pumps, the more he threatens to deplete the Ogallala, which in 1998 produced 66.7 percent of all the groundwater used in the state. By exercising his rights, he is also prompting other property owners to use up a waning resource as fast as they can. He may well be starting the last great water war in Texas. The danger is obvious and confirmed by historical precedent: When water is pumped to the point that it becomes too expensive to pump deeper, the Panhandle will run dry and become depopulated.

Pickens says he has no choice but to pump the aquifer. What he means is that if he doesn’t do it, someone else will, in effect, rustle his water. So he’s got to pump now. He’s hoping to find enough customers along one of three pipelines he’s considering building to either Fort WorthDallas, San Antonio, or El Paso.

He has already got plenty of competition. His most immediate competitor is the Canadian River Municipal Water Authority, which Pickens says spurred him to action when it bought 42,765 acres to develop a water field near his land four years ago. In the fall the water authority will begin pumping and moving the water some 35 miles west to Lake Meredith, which provides water to eleven Panhandle communities, including Amarillo and Lubbock.

Pickens has other rivals as well. Two years ago the City of Amarillo bought a 71,000-acre spread adjacent to Pickens’ Mesa Vista Ranch to mine water, though officials say they won’t start pumping for another 25 years. A fourth water exporting group, with 190,000 acres under option, was formed last year by Amarillo lawyer Ronald Nickum. Pickens complains that at some point those straws will drain his own reserves. If he holds back, his land loses value. “I sure can’t wait twenty-five years,” he says.

How serious a threat is unregulated water mining to the Panhandle? To see what happens after the profits have been made and the water is all gone, consider two Panhandle counties west of Roberts, Dallam and Hartley. Irrigated farming there in the past fifty years has been so intense that most of the Ogallala has been drawn down below the point where it is economical to pump the water out. Some farmers have reverted to so-called dryland techniques, relying on the region’s scant rainfall. Others simply left. Or look at Carson County, which is just southwest of Roberts County. Thirty years ago it had a booming farm economy. There were two farm-equipment dealers and two automobile dealerships. But the economy was based on irrigation farming, which caused the groundwater to dry up. Today, one farm-equipment dealer struggles on and there is no new-car dealership.

But the Panhandle is not the only place that’s going dry. Last summer Jacob’s Well, a massive landmark spring near the Hill Country town of Wimberley, stopped flowing for the first time in recorded history. It had continued bubbling through the great drought of the fifties without pause. But back then golf courses and shopping malls and thousands of newcomers on subdivided ranches weren’t sucking the aquifer dry. Wimberley must now deal, one way or another, with the effects of unregulated pumping. The town of Throckmorton in North Texas pumped its own nearby lake dry and was forced to build a fifteen-mile pipeline to a line that served the town of Graham. The community of Blanco, near Austin, which takes its water from the river of the same name, simply ran out. Water had to be trucked in. This past winter the Rio Grande dried up before it reached the Gulf of Mexico. Too many towns and cities and too many farmers on both sides of the border had pumped too much of it. The United States says Mexico owes us water, but there is no water to give. Upstream, the once-massive International Falcon Reservoir is filled to less than 20 percent of its capacity. It is so low that the old Mexican town of Guerrero, which was submerged when the lake was filled in 1954, has reappeared. Even Houston, notorious for having too much water lately, is constantly fighting a phenomenon called subsidence—in which the ground level sinks—caused by water being pumped from under the surface.

In the water business the rule of thumb is that no one really cares about supplies until the moment he turns on his faucet and nothing comes out. That hasn’t happened yet. But the simple fact is that escalating growth is placing enormous demands on rivers, creeks, springs, and lakes, and stressing already overused aquifers such as the Ogallala and the Edwards. These demands are not, in the long run, sustainable. Groundwater, the source of more than half the water Texans currently use, is being depleted so rapidly that it can supply no more than 20 percent of the state’s needs over the next fifty years, forcing almost every big city to do what Los Angeles did almost a hundred years ago—find water somewhere else, even if it means drying up a distant farming community. When water mining and water exportation kick in, and your water bill starts multiplying as many times as the market allows—if you can get the water—you may have cause to look a whole lot closer at what Boone Pickens wants to do in Roberts County.

Texas is the only western state whose groundwater use is defined by rule of capture. The law was upheld by a 1904 Texas Supreme Court ruling that groundwater’s properties are “too secret, occult, and concealed” to establish a set of rules regulating its use. The rule actually worked for the first 150 years of statehood with a minimum of violence, murder, and corruption. A 1949 law and enough instances when the civic wells ran dry in the fifties inspired the creation of numerous groundwater districts across the state, particularly in the Panhandle and West Texas. (They included the Panhandle Groundwater Conservation District, formed in 1955 to oversee the pumping of the Ogallala.) The basic idea was to set up a public body to protect farmers against other farmers taking more than their fair share. Each district oversees a specific underground reservoir and can regulate and monitor its use. But their regulatory power has seldom been tested in the courts, and experts say it is highly unlikely that they could prevent a landowner like Pickens from pumping.

In Texas, rule of capture is considered so sacred and such a cornerstone of property rights, that the Legislature has never mustered the political courage to overturn the law. In 1997 it came as close as it could, passing Senate Bill 1, a landmark piece of water legislation that created sixteen regions in Texas and required them to come up with plans to ensure groundwater supplies for the next fifty years. It was a nice idea, but the rule of capture still trumps groundwater districts, as affirmed last year by the Texas Supreme Court. The court upheld the Ozarka Water Company’s right to capture water under its property and bottle it, throwing out a lawsuit filed by neighboring East Texas landowners who claimed their wells, creeks, and streams were running dry thanks to Ozarka. SB 1 also made possible the transfer of water from one river basin to another, which solved critical water-planning issues for San Antonio and Corpus Christi. But that also opened the door for water to be pumped and piped from anywhere in Texas. This caught the attention of people with experience in extracting a resource from the ground and making money from it.

What those people—Pickens among them—want to do is little different from what many others are already doing. Ozarka is tapping its spring in East Texas. In Central Texas corporate giant Alcoa threatens to deplete its neighbors’ water tables by selling groundwater to San Antonio. In Buda, south of Austin, T. J. Higginbotham, a resident with 49 acres, has applied for a permit to pump fifty million gallons, about half of what the rest of Buda currently uses, to sell it to developers who are building subdivisions nearby. Wannabes include forestry giant Temple-Inland, the largest landowner in East Texas; the O’Connor ranching dynasty of Victoria; and numerous farmers along the Rio Grande.

Of course, all that potential pumping at some point bumps up against the state’s new water law. In accordance with SB 1, the Panhandle Groundwater Conservation District set a goal to take no more than 50 percent of what’s left in the Ogallala Aquifer in Roberts County over the next fifty years. In theory, it’s a good idea. But hydrologists say that if all four of the current competing groups in the county pump at the same time, their simultaneous withdrawal would exceed the allowable rate of depletion. If that happens, the district will have to slap restrictions on pumping, which starts to sound a lot like a water war.

“That’s about four hundred thousand acres in water rights that could be exported from Roberts County,” says Roberts County judge Vernon Cook. “Under current law, you can export one acre-foot per year for every acre of land you own. [An acre-foot is the amount of water needed to cover an acre of land to the depth of one foot—326,000 gallons.] If all those acres are worked, in fifty years they will have pumped twenty-one million acre-feet of water. Roberts County has a total of twenty-seven million acre-feet of inventory. I’m not a rocket scientist, but that’s not fifty percent of what’s in reserve.” And these groups are not the only ones in a rush to move water out of Roberts County. “I’ve got landowners standing in line wanting to sell their water too,” Judge Cook says.

What scares Cook most are the entrepreneurs like his old acquaintance Boone Pickens. “I used to be in the oil and gas business,” he says. “I know the oil and gas mentality. And that scares the phooey out of me. With the Canadian River Authority group, it’s in their best interest to conserve resources. The same with the City of Amarillo, which says they won’t tap into their supply for at least twenty-five years. My concern is the oil and gas mentality applied to water—pump it as quick as they can get it, make their money, and go away. I’m concerned about that kind of attitude on a finite resource, especially the Ogallala. When it’s gone, it’s gone. There’s no alternative.”

There are plenty of people who believe that, given the chance, Panhandle residents will pump their wells dry by choice, in part because they know irrigation farming there can’t last forever. They need only look at what happened in counties like Dallam, Carson, and Hartley to see that it’s true. “In a lot of rural areas, the best hope is to put that water asset together, harvest it, and ship it off,” says C. E. Williams, the district manager of the Panhandle Groundwater Conservation District. “If the infrastructure was in place, we’d turn the Panhandle from ag production to water supply for the whole state, with a common-carrier pipeline involved. Landowners would get a higher value and a higher price [for water] than other commodities.” As Williams sees it, water mining is a last chance to pull value out of the land, a found opportunity. At least this way, the land will provide a livelihood for another generation or two, a much brighter scenario than what faces the rest of the Panhandle. But there’s another even more ominous implication from the drawdown—the Canadian River going dry, since a major source is the Ogallala Aquifer. And if that happens, Texas would face a federal intervention because the state would not only be harming a threatened species of minnow but also violating the Canadian River Compact, which mandates a certain river flow downstream into Oklahoma and Arkansas.

The inability to see more than fifty years beyond the horizon is practically a regional trait. The Ogallala has provided sustenance since the arrival of agrarian society in the late nineteenth century. The introduction of the right-angle pump in the fifties turned the plains green and productive. But by the seventies, portions of the aquifer began to run low. Extraction of water from the Ogallala has been so profound that parts of the vast reservoir beneath Texas have lost more than 50 percent of their capacity over the past half-century—enough that farming in some areas is no longer economically viable. Once the “good” Ogallala water is gone (the bottom water is brackish), it’s dryland farming or nothing. Boone Pickens is just following local tradition.

But first he needs to find a buyer for his water. Right now, none of the three pipeline destinations sketched into Mesa Water, Incorporated’s PowerPoint presentation are in dire need. The Metroplex has abundant surface-water supplies; San Antonio just wrapped up long-term deals with the Lower Colorado River Authority, the Guadalupe-Blanco River Authority, and Alcoa to buy water; and the $1,775-per-acre-foot estimated tab to deliver Roberts County water to El Paso makes desalinating brackish freshwater from the bottom of the local aquifer cost-effective.

Still, since it’s Pickens who’s talking, you can’t help but believe that somehow, some way, he’s going to make some money out of this, even if he’s already invested a couple million. In the meantime he makes a first-class poster boy. Back at Love Field after a day at the ranch, Pickens graciously offers to sign a copy of his book Boone In front of his signature, he writes, “Call me if you know someone who wants to buy some water.”

Tom beard, a rancher and an attorney from Alpine, isn’t sure jumping on the phone to Pickens is such a good idea just yet. “Mr. Pickens’ proposal is predicated on the assumptions that water mining is okay, with some limitations, and that water is a commodity like any other,” Beard says, standing beside a running spring hidden in the folds of a barren slope in the Barrillas Mountains. “There are many people involved with water in Texas—so-called environmental types, landowners, water district folks, a mixed bag—who are adamantly against both assumptions.”

Beard is the chair of the Far West Texas Water Planning Group and an advocate for rural interests in a region that makes Roberts County look like a wetland. He has the physique of a bantam rooster and the disposition to go with it. Beard used to be a staunch proponent of the rule of capture. “Ten years ago, we’d of had a fight right here if you argued it with me,” he says. The long dry spell and cities going dry two hundred miles away have changed his way of thinking.

In March 2000 he wrote an editorial in Livestock Weekly calling for dramatic changes to the rule of capture. Considering the publication’s readership, it was akin to a declaration of war. “Rural Texas and agriculture have two problems,” Beard wrote. “The first is that we cannot compete with Big City (or any other Big Pump) and will lose our water—literally. The second is that we will lose our water rights if we force the State of Texas to start regulating water because we insist on defending the Rule of Capture to the death. I do not want somebody to take my water, and I do not want somebody to take my water rights.”

Beard’s solution is a system of “correlative rights,” in which property owners may pump groundwater but only as long as it doesn’t unfairly impair their neighbor’s ability to pump water. He proposes to use sophisticated hydrologic science to settle disputes and establish pumping rates. “Agriculture and rural Texas have been the defenders of the rule of capture,” he says. “If we modify the rule slightly, we can keep it. And we can keep the State of Texas out of our business and off of our property.”

But to do that, Beard and other West Texas residents are going to have to reckon with the apparently bottomless thirst of El Paso, 220 miles to the west, a city that is forever short of water. From the office of Ed Archuleta, the general manager of Water Utilities for the City of El Paso, it is possible to see just how bad things have gotten. Archuleta has the daunting task of finding 130,000 acre-feet of water a year for this city of 750,000 in the heart of the Chihuahuan Desert, where the average annual rainfall is eight inches. The Rio Grande is largely spoken for by farmers, and the city’s primary source of drinking water, the Hueco Bolson, is expected to run out of good water within twenty years at the current rate of withdrawal. Unlike aquifers, which are recharged by rains soaking into the soil, bolsons are closed, finite underground pools. Worse, the shallower portion of Hueco Bolson that extends beneath Ciudad Juárez—that city’s sole source of water—is expected to go dry within four years. Juárez, which only began to put together a master plan earlier this year, is ill-equipped to cope with the looming crisis. Like it or not, that’s El Paso’s problem too. It’s hard to ignore that many thirsty people on the other side of the ditch. “We have to practice total water management,” Archuleta says. “We’re never going to have a lake or an iceberg to provide for our needs.”

The future of water in the half of Texas west of Interstate 35 is on view in El Paso today. Watering restrictions are permanent, in force year-round. Water audits are free to any resident who wants one. You can’t water your lawn in El Paso between ten in the morning and six in the evening from April to September. Customers such as the University of Texas at El Paso who use more than one million gallons per day are required to have a conservation plan approved by the Water Utilities board. Two hundred thousand low-volume showerheads have been given away. Residents receive $300 rebates for switching from evaporative coolers (a.k.a. swamp boxes, which use water) to more efficient refrigerated air conditioning.

Until his recent transfer to another city department, Tim Grabe was one of El Paso’s two full-time water cops. He and four temporary workers handled calls and e-mails reporting water abuse. They prowled the streets, looking for streams and trickles in the gutters where they shouldn’t be, taking photographs and videos to document the waste, and issuing citations for class C misdemeanors with fines ranging from $50 to $500 to offending parties. Together they issued 10 to 30 warnings and tickets a day, depending on the time of year. They handed out 5,000 citations last year, up from 1,500 the year before. Most were for water discharged onto public rights-of-way.

On one run up Ryan’s Crossing with him, one of the more affluent-looking residential streets on the west side of the Franklin Mountains, he pointed out a typical problem. “This subdivision was designed years before water conservation was implemented in 1991,” Grabe says. He noted a preponderance of turf grass, officially discouraged by the city. “Fescue requires watering year-round, and during the summer, a lot of water. The problem here is with the sprinklers. The water is coming out of the head rather than going into the soil.”

Grabe was convinced that conservation programs and enforcement are effective. Average per capita use in El Paso has dropped from 200 gallons a day to 159 gallons since conservation measures became law ten years ago. That compares to an average 230 gallons in Dallas. But it’s going to take more than that, he said. “The city is going to have to eliminate turf grasses from parks someday and eliminate all front-yard grass over time. New pools are already required to have filtration, as opposed to the old drain-and-fill method of cleaning.”

Drought anywhere in Texas is devastating. In El Paso it’s a permanent condition that threatens the city’s economic expansion. That has prompted Ed Archuleta to develop several strategies, including a desalination plant to treat up to 29 million gallons of brackish and otherwise undrinkable water daily, of which there is an abundance in the Hueco Bolson and other groundwater in West Texas. He is also making more deals to purchase water from irrigation farmers who control the water rights of the Rio Grande. “There’s enough water within 150 miles of El Paso to take care of our needs for the next fifty years,” says Archuleta. “We have that before we need to look at importing it from farther away.” Considering that the part of Texas beyond the Pecos River has more than seven million acre-feet of groundwater, the biggest potential sources of all are local ranches. The city has purchased two ranches near Van Horn and Valentine over the past eight years for the express purpose of mining water from deep underground pools and piping it back to El Paso. It is currently eyeing a third area around Dell City, west of the Guadalupe Mountains, where irrigation farming has thrived from the one aquifer in the region that can be refilled by rain.

Pumping water from Valentine and Dell City seems inevitable. Valentine’s water is exceptionally sweet; Dell City’s water, though salty enough to require treatment, is renewable. You can pull 50,000 acre-feet a year out of the aquifer, and nature replenishes it with runoff from rains. The big trick is building a pipeline to get that water to El Paso. That’s where a gentleman from El Paso named Woody Hunt enters the picture.

Hunt owns the Hunt Building Corporation, whose core business is constructing military housing. He’s the first University of Texas regent from El Paso, appointed by then-governor George W. Bush. He was a major contributor to Bush’s gubernatorial and presidential campaigns. He is also an unabashed true believer in El Paso’s future.

In March Hunt Building released the findings of a year-long study concluding that construction of a pipeline from Valentine, Van Horn, or Dell City to El Paso is feasible and that water can be delivered to El Paso at reasonable market rates. The study also hinted, not surprisingly, that the Hunt Building Corporation is the ideal entity to build the pipeline and have water flowing into the city within three years. In exchange for that effort, Hunt Building would have what amounts to complete control over El Paso’s imported water. It would also be able to orchestrate where future development will occur, courtesy of the rule of capture, because Hunt Building has also purchased 5,000 acres of farmland in the Dell Valley. The company’s likeliest partner in this venture is Philip Anschutz, the Denver tycoon who owns almost half of the 40,000 cultivated acres in the Dell Valley. As a major investor in Union Pacific Railroad, he also controls the right-of-way crucial to the construction of a pipeline.

“In the past few years, Woody Hunt made a conscious decision to invest in developable properties in El Paso,” says Hunt’s spokesperson for water operations, John Edmonson, “and in particular, high-quality long-term developments that are ten-, fifteen-, twenty-year projects like you see in Tucson and Albuquerque.” Hunt Building owns more than a thousand acres between Interstate 10 and the Franklin Mountains on the western edge of the city and controls another one thousand acres through partnerships.

“The city of El Paso isn’t running out of water,” says Edmonson. “The question is, Where is the future water coming from? As developers, one thing that has to concern you is the ability of that community to grow, and a big component of that is water and the availability of water. That’s the basis of Hunt Building’s interest in water. Woody cares a great deal about El Paso. That’s why I’m here. We want to tell developers and corporations that they can invest $35 million in an El Paso project and know they’ll have water.”

The billboard on the road into Dell City that proclaims it the “Valley of the Hidden Waters” is faded, with flecks of rust around the edges. Every other building on the edge of this community of six hundred is vacant. As many fields in the distance lie fallow as are under cultivation, reclaimed by the desert. The Dell Valley has a striking beauty. It is a high flatland among the extinct volcanoes and bare rock slopes of the Cornudas Mountains to the west, separated by a long ribbon of salt flats from the Guadalupe Mountains to the east. When red chiles are dangling from the bushes and a light powder of snow dusts the peaks, there’s not a more majestic view of Texas’ highest range.

Mary Lynch says she never gets tired of looking at the Guadalupes. “It’s sacred to me,” she says. “I just think it’s beautiful.” She’s admiring the view outside the offices of the Hudspeth County Heraldthe weekly she edits and her husband, Jim, publisheswhich last November declared in a front-page headline “New Water Wars on the Horizon; Get Ready to Fight.”

Jim Lynch’s family arrived in the Dell Valley around 1950 from the Central Valley of California, where they had learned firsthand the miracle of irrigation. The Dell Valley has been explored for oil and gas, and though little was found, a tremendous amount of groundwater was discovered. Farms popped up like mushrooms. Almost overnight more than 40,000 acres went into production. Through the fifties and sixties, cotton, an extremely thirsty plant, was the valley’s main crop. Dell City had six cotton gins. Since the eighties, when commodity prices plummeted, agriculture has declined. Ninety percent of what’s currently farmed is alfalfa, another water-intensive crop. The remainder consists of chiles, winter grains, silage, and to a lesser extent, tomatoes, melons, and other truck-farm crops. Phillip Anschutz has 150 acres in wine grapes.

The Lynches’ paper has been covering the rural-urban water battle in West Texas longer and in more detail than any media outlet in El Paso or elsewhere, long enough to realize the increasing odds against holding on to their way of life. “We all know El Paso is bigger than any of us, and if they choose to take this water, we don’t have the money collectively to fight them,” says Jim Lynch, brushing back his snow-white hair. “Whether you’re right or not, if you have the money to stay in court, I can’t stay with you. Phil Anschutz is one of the wealthiest men in America. If he’s together with Hunt, there’s no stopping them.”

The rising cost of irrigation—more than $100 an acre and climbing as fast as natural gas prices—has already been squeezing farmers over the past several years. “Some people have the attitude that if they can get more money for their water than for farming, then why farm?” Lynch acknowledges. “A lot of us take a longer view and would like to preserve the rural atmosphere and the farms and see the valley prosper.” But Lynch realizes that it’s unlikely that both will be accommodated. What he’s afraid of is that El Paso or entrepreneurs like Hunt will cut deals with two or three people to take the water, cutting the rest of the community out. “My thinking is, if we have to give up our water, all of us should share in the money. If a few farmers sell out, they’ll make money, the water will diminish, and everyone else will have to go out of business without compensation.” It is not, he admits, a bright future either way. “Up until this, we admired Mr. Hunt for his success, his civic contributions, his buildings. But if he uses his power to take our water and dry up our community, we’re not so admiring.”

Two years ago, the prospect of El Paso sucking Dell City dry was unimaginable to Gene Lutrick, a strapping farmer who wears overalls. Now he’s been converted to Tom Beard’s line of thinking. “I used to be very strong on the rule of capture,” Lutrick tells a noon gathering of the Dell City Chamber of Commerce, of which he is president. “But I’ve been educated. I don’t know if we are going to lose our rights. El Paso, Houston, Dallas, San Antonio, and Austin—they’ve got the votes. If they dry up Texas, they can still import farm products. But where am I going? I’ve been farming here fifty years. I am very opposed to a gallon of water going out of our district.”

The town of Fort Stockton is in the middle of that vague West Texas transition zone where the Permian Basin becomes the Chihuahuan Desert and flat-top mesas turn into mountains. It is known largely as a major food-fuel-motel way station along Interstate 10. For most of its modern history, its sole reason for being was Comanche Springs, the most abundant springs complex this side of the Balcones Fault. Native Americans frequented the springs for thousands of years. Anglo and Spanish explorers, along with adventurers, plunderers, tradesmen, and thieves, relied on it on their long treks west for the same reason, as did the stage lines and the railroads.

The springs also provided for hundreds of small farmers east of town. An intricate system of canals and sluice gates delivered the springwater to the crops. It was said you could float in a tube from the springs to a spot fifteen miles east of town. But in 1955 landowners west of town, including Clayton Williams, Sr., one of West Texas’ most distinguished civic leaders, drilled wells and installed diesel pumps to feed their crops and newly planted fields of pecan trees. Comanche Springs went dry. Without water, the people left and the farms disappeared. You can still see traces of the farms and where the canals were and make out the symmetrical furrows in the desert. The ditches and sluice gates remind me of old photos of the planet Mars I saw as a child showing evidence of Earth-like rivers and streams. They’re signs of a lost civilization, as secret and occult as the water beneath my feet.