I was born in 1984, in the old Dolly Vinsant Memorial Hospital, in San Benito. Me, my mama, and my grandmother lived several miles away from there, outside of Los Fresnos, in a trailer on Old Port Road. Rte 3, box 87 was our address. Our trailer was parked on the edge of a resaca, where we were surrounded by grapefruit orchards and sugarcane, big agave plants and mesquite trees.

My mama did the weather on KVEO, a TV station out of Brownsville. She would sing Billie Holiday and ZZ Top around the house, and I’d sing along with her; that’s when I first started to get into music.

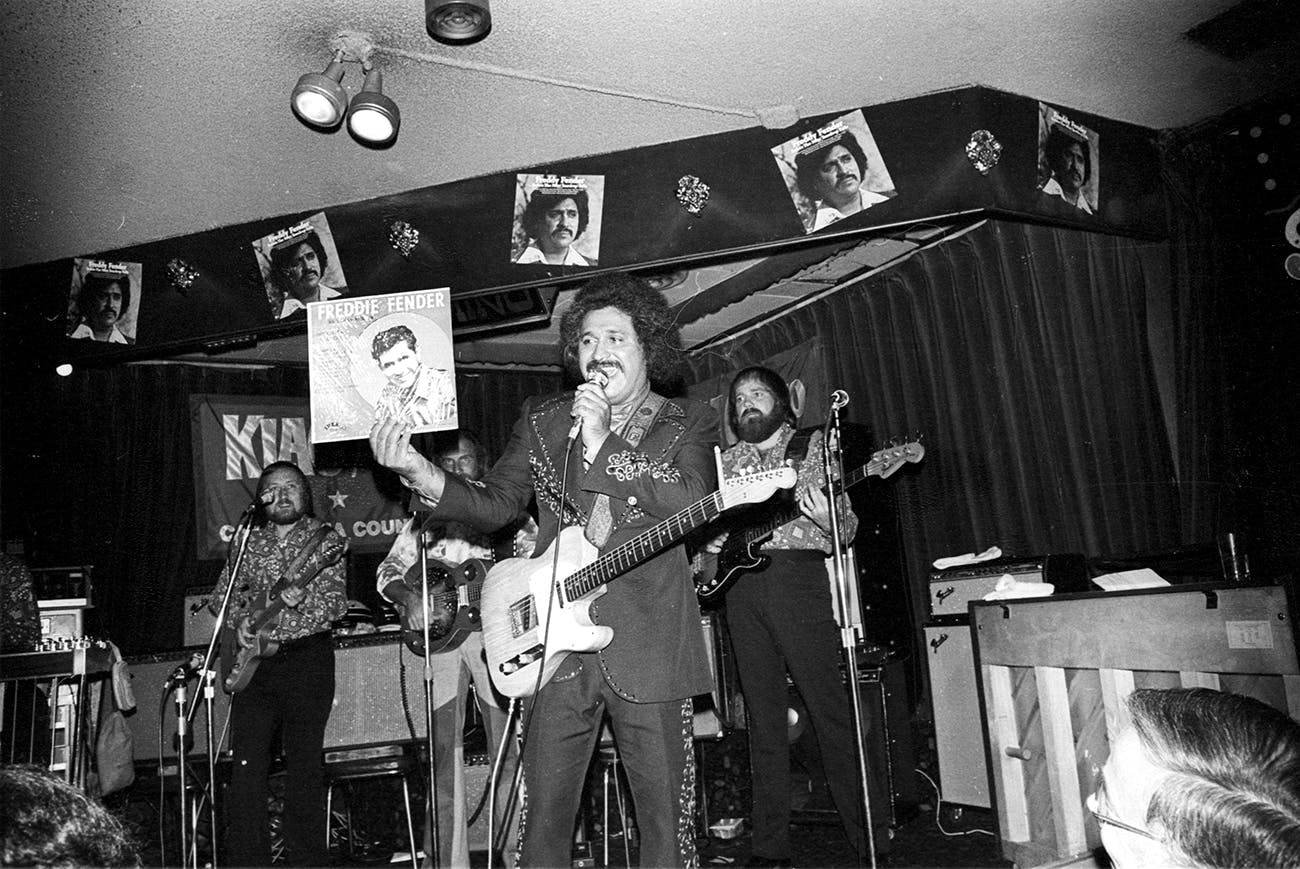

What I remember most about San Benito, though, is Freddy Fender. Freddy was born there in the thirties, and even after he became a big country star, he always came back to play concerts. He was the local hero when I was coming up, the pride of the Rio Grande Valley. He was everywhere.

Some of my earliest musical memories are watching Freddy perform on the Johnny Canales Show, a talent show that focused on South Texas music, like Tejano and conjunto. Selena sang on it when she was thirteen. I loved Johnny Canales—he was so magnetic. They shot the show in the same studio where my mama worked, so she took me to see it a few times. I loved the variety show aspect, the costumes, and the people that Johnny brought on. At home I’d stand on a milk crate and pretend to be him.

Whenever Freddy appeared on Johnny’s show, he wore the flashiest suits and had the biggest hair! He also had the sweetest voice and was a really positive presence. I’d see his tapes and albums with those amazing covers, like the back of Before the Next Teardrop Falls, which has a picture of him with his leg hunched way up. I remember seeing footage of him and Dolly Parton singing the title track and they were so cool together. “Wasted Days and Wasted Nights” was one of his biggest hits. I can remember being in the trailer and hearing that song.

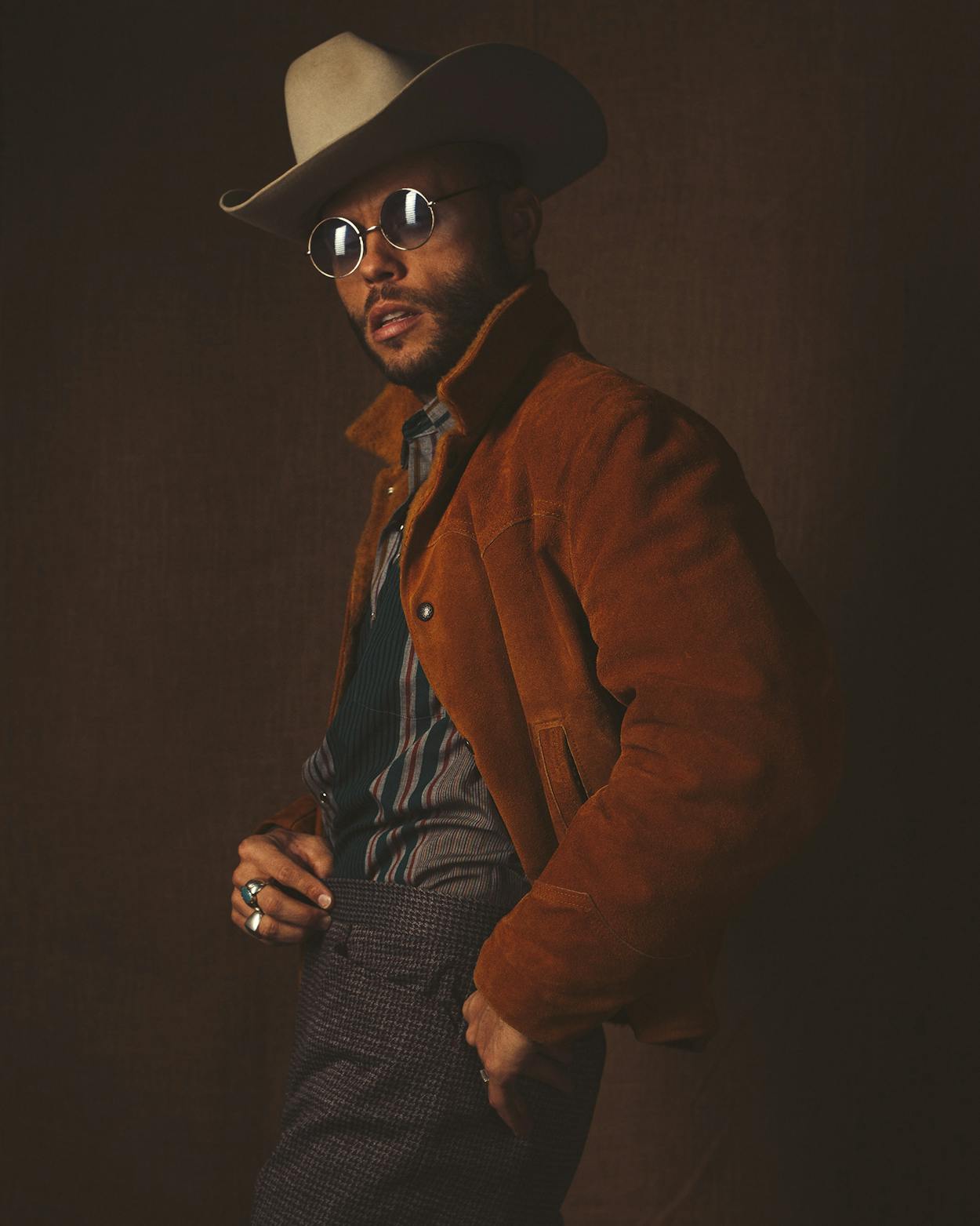

I didn’t realize it then, but I wound up doing a lot of things that Freddy had done years before me. Like, we both used stage names. Freddy was born Baldemar Garza Huerta and came up with Freddy Fender—the surname is taken from the guitar brand—because he knew it would help him sell records to, as he put it, “gringos.” I was born Matthew Charles Crockett, but I started going by Charley fifteen years ago because my grandfather’s name was Charley Crockett and because, well, Matthew—I knew that wasn’t gonna pop. Freddy and I also came up with alter egos: he called himself “El Bebop Kid” when he started playing rock and roll, in the late fifties, and I go by Lil G. L. when I do my more traditional country and blues songs.

We also both got busted for weed. The difference is, it was so much harder in his time: he served three years in Angola prison, in Louisiana, for a couple of joints! I had a lot more on me than that. In 1963 he was set free early by the Louisiana governor Jimmie Davis, himself a singer who loved the way Freddy sang. Me, I pleaded with my judge. I was busted in Virginia, shortly before I was going to perform at the Granada, in Dallas—my first headlining show at a theater, with a band. I sent the judge my first two CDs and begged him to let me do unsupervised probation—and he said yes. Music saved Freddy and me.

We also both spent about five years in New Orleans, learning our chops. He went there in the sixties after he got out of prison; he worked as a busboy and would sit in with singers like Art Neville at all those little clubs in the French Quarter. That’s where Freddy picked up a lot of his R&B feel.

I spent some time in New Orleans, too, learning all about American music—early country, jazz, and blues. Like a lot of people from my generation, I was a hip-hop kid; that’s what influenced me, that’s where I learned meter and how to improvise. Around 2006 I was traveling around the country and I wound up in New Orleans, performing with hip-hop dudes on street corners.

At that time, after Katrina, there were so many young musicians in New Orleans. I’d see kids playing Appalachian music on banjos, young women playing fiddle tunes, gospel bands covering “Just a Closer Walk with Thee.” I discovered classic songs like “All of Me” and started forming bands: brass bands, bands including a guy with a snare and bass drum, mixed-up bands of whoever was around.

I learned how to swing in New Orleans. If you listen to banjo music from Tennessee, early blues from Texas, early traditional music from Louisiana, you’ll hear that they’re playing downstrokes, on the first and third beat of each measure. New Orleans taught me to swing that old traditional beat. It’s not difficult, it’s just a paradigm shift—playing on the 2 and the 4 instead of the 1 and the 3.

I was learning what American music is built on. You can hear that on A Stolen Jewel, my first album—it’s country music but it’s blues, it’s soul, it’s Louisiana. It’s Texas.

I found my voice singing my kind of country music, just like Freddy Fender did. Music from South Texas is country as hell: the murder ballads, the revolutionary border music, the story songs. But there’s nothing pure about it; it takes in influences from all over. Freddy spent his career singing not just country, but conjunto, rock and roll, and R&B. When this middle-aged Hispanic dude with a huge Afro took “Wasted Days and Wasted Nights,” a mash-up of country music and “swamp pop” from Louisiana and Southeast Texas, to number one on the country charts, it shouldn’t have been a surprise.

I covered “Wasted Days” on my second record, In the Night. I changed it some. Freddy played it in a major key, E, and I took it to a D-flat minor and sped it up. He’s doing a waltz, I did a 4/4 beat and changed the melody a little.

When I sing Freddy’s song, I feel the damp energy of Texas nights—playing in smoky bars in Port Arthur, the bars on Greenville, in Dallas. It’s such a visual song. Even when I was a kid, it was so powerful. Who doesn’t have wasted days and wasted nights in their lives? Getting messed up, hurt by love, going nowhere with your life?

Freddy doesn’t get much credit for his music, but I think he’s as much an innovator as Chuck Berry—with his rhythms and records crossing so many genres. One place Freddy does get respect is in San Benito, where his face is on the city water tower. After I put out my sixth album, The Valley, last year, people down there started saying they should put my face on the water tower too. I haven’t earned it yet—I’m not ready to get up there with Freddy. But I tell them, if you do put me up there one day, keep Freddy on the front side, facing the highway. Put me on the back, where I can look out over the orchards and the sugarcane.

This article originally appeared in the April 2020 issue of Texas Monthly. Subscribe today.

The Stories Behind the Music

Texas musical luminaries reveal the family histories, powerful influences, and big breaks that made them the artists they are today. Read more.

- More About:

- Music

- Country Music

- Charley Crockett

- San Benito