I used to sit in a certain room of my house and try to do what I’m doing now: write.

The room was quiet, and the window had a clear and unobstructed view of only my neighbor’s fence, which was fine since I wasn’t there to be looking out the window. Because the window faced south and the fence was just six feet away, the sunlight was neither harsh, as it can be most of the year in Texas, nor especially soft and inspiring, in the way that movies have of showing writers at work. Sometimes I went into the room early in the morning, when the house and the entire neighborhood were still quiet; other times it was evening, after our two-year-old, just across the hall, was fast sleep for the night, or so my wife and I hoped.

The room measured eleven feet by twelve feet, not especially large but not totally cramped either, and the carpet was oatmeal-colored. It had a popcorn ceiling, and the light fixture on the fan hung just low enough for me to bump my head. So that our toddler wouldn’t lock himself in when wandering around, the door didn’t have a lock, which of course meant that our toddler might show up unexpectedly. The room was far from perfect, but for two years it was where I worked.

This arrangement changed in 2009, when my wife and I had our second child and we suddenly needed a place to put the baby. The solution was obvious, and overnight my office turned soft and cuddly. Where there had been a desk and computer now stood a crib. Where I’d covered the wall with note cards tracking the plot of a novel now spun a mobile with cute pink animals, stuffed bunny rabbits and lambs and owls frolicking after one another in an endless loop. Where there had been a bookcase now awaited a changing table, stocked with onesies and rompers and diapers and wipes and soft lighting and everything else a little bitty person required at all hours of the day and night.

My new office was now the kitchen table, though only on those occasions when the two-year-old wasn’t already there, eating a meal or one of his many snacks. When I had the place to myself, I’d find smears of applesauce on my note cards or a crushed Cheerio under my laptop. It wasn’t long before we knew we needed to add a new room to the house.

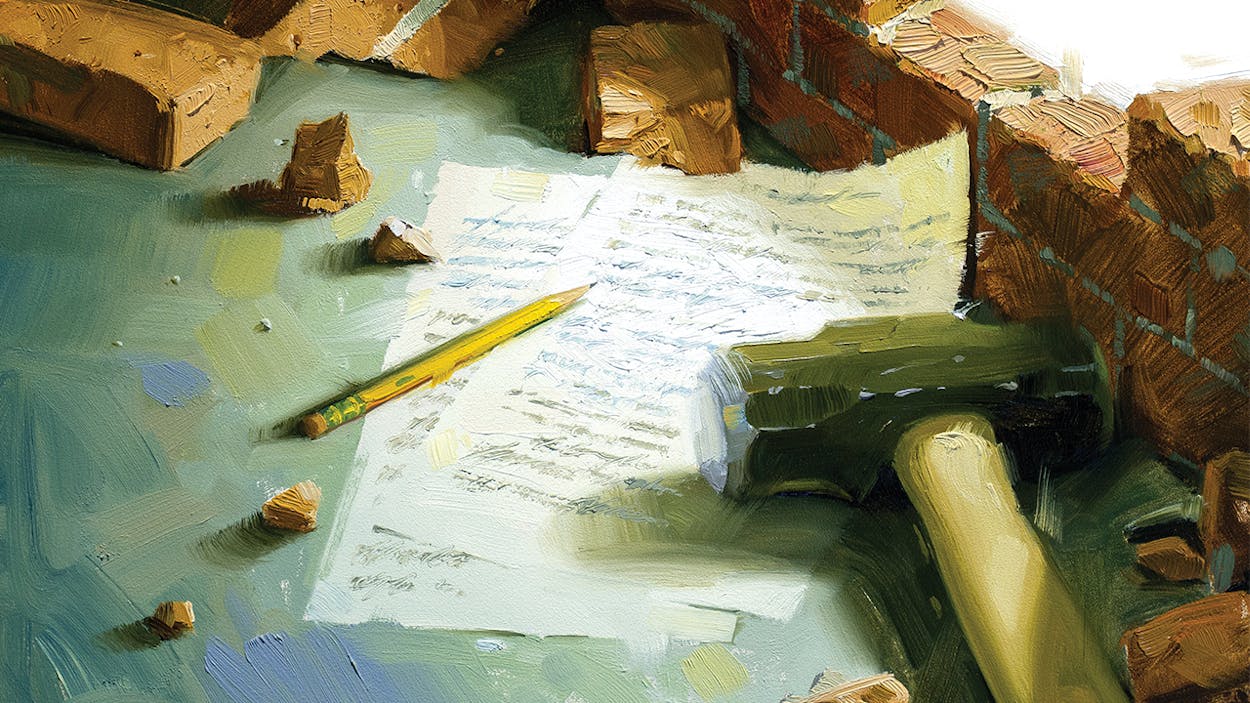

It was about then that a friend happened to recommend his building contractor. Because we’d eventually need the blueprints approved by the City of Austin, the contractor suggested we hire an architect, an expense we quickly learned would take a considerable bite out of our budget, for the basic task of designing a ten-by-twenty-foot box with electricity and a small bathroom. So the contractor recommended a draftsman, who would more or less do the same job but for cheap. It didn’t escape me that we might be sealing our fate by cutting a corner, and the very first one at that, by passing on a pricey architect to go with a price-friendly draftsman.

At that point the one remodeling project I’d seen was back in Brownsville in the early seventies, when my father had hired a man named Jiménez to build us a carport. My father didn’t hire the man for his craftsmanship as much as he did for his availability and what little he charged. Labor, in just about any form—construction, child care, house cleaning, yard work—comes dirt cheap along the border, where the meager wages are still more than what people, and by “people” I mean people from the other side of the river, earn in Mexico. Someone at Holy Family had recommended Jiménez (I never learned his first name, since most of the men my father worked with or hired for odd jobs went only by their last names—Bazan, Zapata, Cortinas, Gavito—or at least to him they did), and as far as we knew, he was from this side. He wore leg braces that attached to the bottom of his work boots, but he had no problem climbing a ladder or steadying himself on our gabled roof.

With his teenage son helping dig the holes for the wooden posts, Jiménez had the framework up in a couple of days. But after that, he rarely worked two days in a row. If it even looked as if it might rain, he wouldn’t show; if it was clear and breezy, he often wouldn’t show up either. This went on for weeks. The neighbors must have thought my father had run out of money to buy the rest of the materials. My mother began parking the Oldsmobile inside the shell of the carport, as though if she did it enough times, the roof might finally appear overnight.

My father would have complained to Jiménez, but he thought his missing work had something to do with his leg braces. Maybe my father felt sorry he wasn’t paying him more. In the end, it took close to three months for Jiménez to finish the job. “Lo barato sale caro,” I remember my father saying. By which he meant, you get what you pay for.

Now, almost forty years later, I had convinced myself that my father’s remodeling project was different from mine. To begin with, our contractor would be looking over the plans, as would the city inspector, and between the two they’d be able to spot any problems in the draftsman’s design. My father, on the other hand, hadn’t hired a contractor or even a draftsman—Jiménez included the design in his bid—and to save money on the city permit, the construction had gone unreported.

The draftsman, an older Anglo man with a salt-and-pepper mullet, met with my wife and me on a Sunday afternoon. He pulled up to the house in a silver pickup, the kind that’s extra-wide in the back and always seems to take up most of the driving lane. He wore a long-sleeve button-down shirt, Wranglers, and kiltie boots. When I greeted him at the front door, I heard a faint drawl in his voice. We sat at the kitchen table, and my wife and I explained the project as he took notes on a steno pad. A few days later, the blueprint arrived in a cardboard tube on our front porch.

The new office, as we’d discussed, would be situated alongside the garage. But according to the blueprint, the draftsman had us keeping the exterior wall of the garage and using this exposed brick as my interior wall, which was something we’d already said no to the first time he’d brought it up. Since the rest of the design looked fine, though, my wife said she would just have him revise this one part of the blueprint. Next thing I knew, the exposed brick was no longer an issue and our contractor was telling us he had an opening and could start the next week. It looked as if I might have my new office by the end of the summer.

Then, a couple of nights later, my wife said there was something she needed to tell me about the remodeling project but she didn’t want me to get upset. I sat down on the edge of the bed. She explained that the draftsman had thought we should at least see the wall before rejecting his idea. And then, in passing, he’d mentioned that if we didn’t like how it looked, we could still have the bricks removed and put up drywall, and not for much more. “Just get yourself some Mexicans to do the work,” he’d said, trying to be helpful.

Those were his words. “Get yourself some Mexicans.” Seriously? It wasn’t that I hadn’t heard this sort of sentiment before, but it had always been out there, in the world beyond our front door. Maybe it was my being from the border that made me sensitive to this kind of talk. I’d like to think it would have bothered me regardless of where my people came from.

“What are you going to do?” my wife asked.

I was about to respond, when one of the two baby monitors chirped. We stared at them both, unsure which of the rooms the sound had come from, but after a few seconds, nothing else happened.

“What do you think I should do?” I asked her.

She shrugged, then glanced back at the monitors.

It crossed my mind to call the draftsman and demand an apology, though I wasn’t sure for what. I went to bed that night and stared at the ceiling, asking myself if I really wanted to spend the next thirty years working in an office designed by this draftsman.

I didn’t have an answer the next morning, but I did know that tossing out his blueprint would mean paying another draftsman to design the same blueprint of my ten-by-twenty-foot box—spending, in the end, as much, if not more, as we would have on an architect—and, because in the meantime our contractor would need to move on to another job, the construction would be delayed by who knows how long. A week? A month? Three months? Lo barato sale caro.

By the time construction began, I’d turned the incident over in my mind enough to understand a few things: (1) the draftsman saying we should hire some Mexicans wasn’t an outright slur, it only sounded like one, (2) his comment didn’t actually mean he thought all Mexicans were laborers because they were unskilled and couldn’t find better work, (3) it did, however, imply that he thought many laborers were Mexican, (4) he was referring to undocumented immigrants who will work for close to nothing and are often taken advantage of by their employers, and (5) not to excuse what he’d said, but the draftsman probably had no idea he was working for a family with Mexican roots, which could have had something to do with my being six-feet-four, light-skinned, and physically nothing at all like a Mexican one might hire to knock down a brick wall. How the hell was he supposed to know that this time it was the Mexican doing the hiring?

I say Mexican, though in truth I’m Mexican American. My family crossed over in 1850, almost as soon as there was a border to cross and long before anyone really cared. In South Texas—because we’re from the border and because many of our families live on either side of the river and because every day we see people making the same journey back and forth and because it isn’t uncommon for us to still speak both English and Spanish, sometimes in the same sentence, and, actually, just because—we often say Mexican when we mean Mexican American, knowing full well there’s a world of difference between one and the other.

Then again, when someone makes a questionable comment, these differences seem beside the point. But having lived most of my life in Texas, I also understand how easy it is for certain things to simply be part of the way we see the world. If every day we see nannies and hotel maids, busboys and dishwashers, janitors and window washers, yardmen and construction workers, all of them dark-skinned and from somewhere south of the border—we imagine—then what we see becomes all we know, all we believe to be true. So, yes, a part of me wanted to give our draftsman the benefit of the doubt, to believe that what he’d meant to say was “Get yourself some cheap laborers” and that only for expediency’s sake had he used the word “Mexicans,” assuming that we were all speaking the same language, assuming that it was easy enough to separate the language from its past.

In George Washington Gómez, a novel about the Texas-Mexico border in the twenties and thirties, Américo Paredes—who also, not so coincidentally, happened to be from Brownsville—walks us through some of the etymology of the word “Mexican,” noting that it was “a symbol of hatred and loathing” for so long that to most Texans its very usage had become hateful and loathsome. “A kindly Anglo hesitated to call a friendly Mexican a Mexican for fear of offending him,” writes Paredes. “The lower lip pushes up and the upper lip curls contemptuously. The pursed lips go ‘m-m-m.’ Then they part with a smacking, barking sound, ‘M-m-mex-sican!’ . . . It is also a word that can be pronounced without opening your mouth at all, through clenched teeth.”

History tells us that this hatred and loathing dates as far back as the Texas Revolution and then the U.S.-Mexican War, when, overnight, Mexicans who had been here all along became American citizens, but second-class ones. If these circumstances have obviously changed over the past 170 years, though, shouldn’t the harshness of that one word also have evolved? Only if you don’t take into account the unease that many people today feel about the rate of immigration into this country. In 2014 the Pew Research Center estimated that there were 11.3 million unauthorized immigrants in the U.S. labor force, with half these workers being from Mexico. Which brings us back to the draftsman. Was he right, merely giving voice to the reality of what we all see and, like it or not, know to be true?

It turns out he was only half right or, depending on your take, half wrong. The two carpenters who ended up knocking down the brick wall were Mexican American, both of them from Elroy, a little town just south of Austin. On their last day of the remodeling, I bought the beer, and together we toasted their work.

I write in the new office just about every morning now. The room has a separate entrance, only eighteen steps away from the house, so I’m close but not too close to the front door. The window looks out onto the front yard, but I keep the curtains drawn so that I’m not too distracted. The wall closest to my desk has a floor-to-ceiling corkboard where I’ve tacked up note cards and, high in one corner, a sepia-toned photograph, taken in the late 1800s, of my great-grandfather.

Sometimes when I’m in the office I think of what the draftsman said and, if I’m feeling kindly, what he meant to say. I also think of the days before I ever had an office and was only learning to write. This was in the late nineties, when I applied and was accepted to the graduate writing program at the University of Iowa. After my first visit to the campus, a friend drove me to the airport so I could fly back to Texas. I remember we were on the outskirts of Iowa City when I asked him to pull over in front of a McDonald’s. Because the parking lot was being repaved, he had to stop along the curb.

“You’re going to miss your flight,” he told me.

“I’m not going in,” I said.

Then I stepped out of the car just enough to gaze over its roof at something I’d never seen, in all my years in Texas. Of the dozen or so men spreading asphalt across the parking lot, all of them were white—young and middle-aged sons of the Midwest—and not one of them was of color, not black, not brown. I almost couldn’t believe it.