From 1978 to 1991, the world capital of mergers and acquisitions, greed, champagne consumption, cuckoldry, and plot twists was a midsized horse farm east of Plano. Behind its wood rail fence stood a white frame house that wouldn’t have looked out of place in any luxury cul-de-sac. Three generations of billionaires shared that home, and for a long stretch of the eighties, they were the most popular television family in the country.

It’s hard, from the vantage point of our Peak TV era, to grasp why Dallas caused such a global ruckus. In 1980, the show was arguably the hottest pop culture entity in existence; about as many Americans tuned in to find out who shot J. R. as voted for president. But today it looks like a relic of the era “before TV got good.” After families like the Sopranos and the Drapers ushered us into the Golden Age of Television, critics started grading series in terms of filmic scope and literary ambition. By those metrics, the Ewings have been tossed into the bin of trashy, campy pop culture, right next to the cast of The Love Boat.

That’s partly because Dallas was, by its own estimation, trashy and campy. The Ewings were more operatically miserable than any other family on TV, they slept around more, and many of them were single-mindedly devoted to ruining other people’s lives for money. Inside their all-American house lurked murder schemes, secret relatives, rare diseases, and an entire season that was all a dream. The show upended our common logic—our moral codes, our sense of cause and effect—with a J. R. Ewing smirk.

But to criticize a nighttime soap opera for absurdity is to miss the point. Dallas leaned into its own absurdity, and in the process, it defined an era and transformed its namesake hometown. Two years before Ronald Reagan became president, and nine years before Oliver Stone’s Wall Street accidentally turned “Greed is good” into a mantra, the Ewings already knew what the eighties were about. The Ewings celebrated excess, and they saw the boardroom, ballroom, and bedroom as overlapping war zones. In all three venues, questions of virtue and civility were dissolved in J. R.’s certainty that “All that matters is winning.”

Spoken by a lesser actor, that line might have seemed like a pretty bleak way of looking at things. But when Larry Hagman said, “A conscience is like a boat or a car: if you feel you need one, rent it,” it sounded like a jingle. When he ruined some poor fool’s life, hundreds of millions of viewers cheered.

While Dallas was selling a new American ideal—not to mention official Dallas aftershave, deodorant, commemorative dishes, 24-karat-gold Southfork belt buckles, and J. R. Ewing Private Stock beer emblazoned with the slogan “If you have to ask how much my beer costs, you probably can’t afford it”—to fans at home and abroad, it was also selling them a new vision of Dallas and Texas. Like the Texans portrayed in Red River and Giant, the characters on Dallas were “full of swagger” and “larger than life.” But they didn’t just rope cattle and strike oil; they orchestrated coups against Communist regimes in Southeast Asia that threatened their oil interests and wore Valentino dresses while they fell off the wagon.

The corporate dealmaker may have lacked the romance of the Texas Ranger, but he was, in many ways, an accurate update. By 1978 Texas was 80 percent urban, and its major cities were booming. The Wild West had become the Sunbelt, and the region needed a new myth. Even if Dallas’s interiors were shot in Los Angeles and its geographical specificity was blurry enough that it could’ve just as easily been titled Tulsa, the show turned Texas into the home of the modern western, where, instead of dying in the town square, the villain NetJets into the sunset after unloading shares in a new company called Enron.

Forty years later, the city of Dallas has turned toward other mythical figures, like Mark Cuban and Jerry Jones. But when we watch TV today, we’re visiting a house that Dallas helped build. Back in 1978, it was rare for a show’s stories to bleed from one episode to the next, for each season to end with a cliff-hanger, and for scripts to foreground a morally compromised protagonist. In 2018 that’s a standard blueprint for prestige television.

In short, for all their resemblance to the cast of The Bold and the Beautiful, the Ewings changed Dallas, changed Texas, changed America, and changed the medium of television. And they still have us in their grip. In compiling this oral history, Texas Monthly wanted to capture all of that. But more than anything, we wanted to hear, from the actors, crew, and creators, what it was like to make this show and how it felt to be at the center of a worldwide mania. After more than 35 hours of interviews, we learned that the stories behind Dallas are nearly as over-the-top as the stories on the screen.

INVENTING DALLAS

Patrick Duffy played J. R.’s brother Bobby Ewing: Oral histories . . . you know, there’s a great—was it Merle Haggard? I think it was Merle Haggard who had the line, “Everything does change, except what you choose to recall.”

David Jacobs is the creator of Dallas and its spin-off, Knots Landing: Here’s the history of the Dallas pitch. I moved to L.A. in 1976 because my ex-wife married an actor and came out here [with our daughter]. I’d never written any TV before; I wrote magazine articles about the arts and books. Made hundreds of dollars a year. The first nine months here, I couldn’t get arrested, but after a rewrite job and a few staff writer things, I had a chance to pitch something to [the production company] Lorimar. I came up with a show about four families living on a cul-de-sac in Southern California, based on Scenes From a Marriage, by [Swedish director] Ingmar Bergman. Yeah, I had high aspirations.

David Paulsen was a writer, producer, and director for Dallas and Knots Landing: The whole thing was a family story based around dining room tables.

David Jacobs: So [my creative partner] Michael Filerman and I go in and pitch, and they responded, “You know, we want to do this, but we want something glitzier. More of a saga.” So as soon as we left, as we’re driving back, I said, “Well, a saga. That means Texas ranches.” I had driven through Texas once, on a camping trip with my daughter, in 1972.

David Paulsen: David Jacobs is one of my closest friends. We have lunch every week. I saw him yesterday. He didn’t know the first thing about Texas.

David Jacobs: I remembered this big billboard there that said “Ewing Buick.” I liked that name, Ewing. After the meeting, I went home and wrote a twelve-page backstory set on a Texas ranch, a saga about the Ewings and the Barneses.

David Paulsen: His structure, which was wonderful, was Romeo and Juliet [Bobby Ewing and Pamela Barnes] and Cain and Abel [J. R. and Bobby].

David Jacobs: Lorimar was very enthusiastic about the backstory, and they said, “We have [the actor] Linda Evans under contract; we’re looking for something for her.” So I wrote a script over Thanksgiving weekend 1977, and when I finished it, I put “Untitled Linda Evans Project” on the cover. Then Michael called me and said, “ ‘Untitled’ doesn’t sound good. It sounds like you don’t know what the hell you’re doing.” I asked him what he’d call it, and he said, “Dallas.” And I said, “Dallas? Kennedy was killed in Dallas. Well . . . at least they won the Super Bowl.”

Matt Zoller Seitz is the television critic for New York magazine and grew up in Dallas while the show was airing: Let’s just say that the makers of Dallas weren’t really big on doing homework. There were not herds of cattle tracing across Grand Prairie, and there weren’t fields of oil wells outside Dallas. It bore about as much relation to life in actual Dallas as Lost in Space did to the history of space exploration.

David Jacobs: CBS called Michael and me in and asked if I could write [five] episodes [for a proposed Dallas miniseries]. I asked Mike, “Should I go to Dallas and check it out before I write the show?” He said, “It doesn’t matter. You’ll go after, later.” And I said, “Okay. I’ll write the stereotypes, and then I’ll go to Dallas later and pull it back.” So I wrote the stereotypes, and then we all went to Dallas.

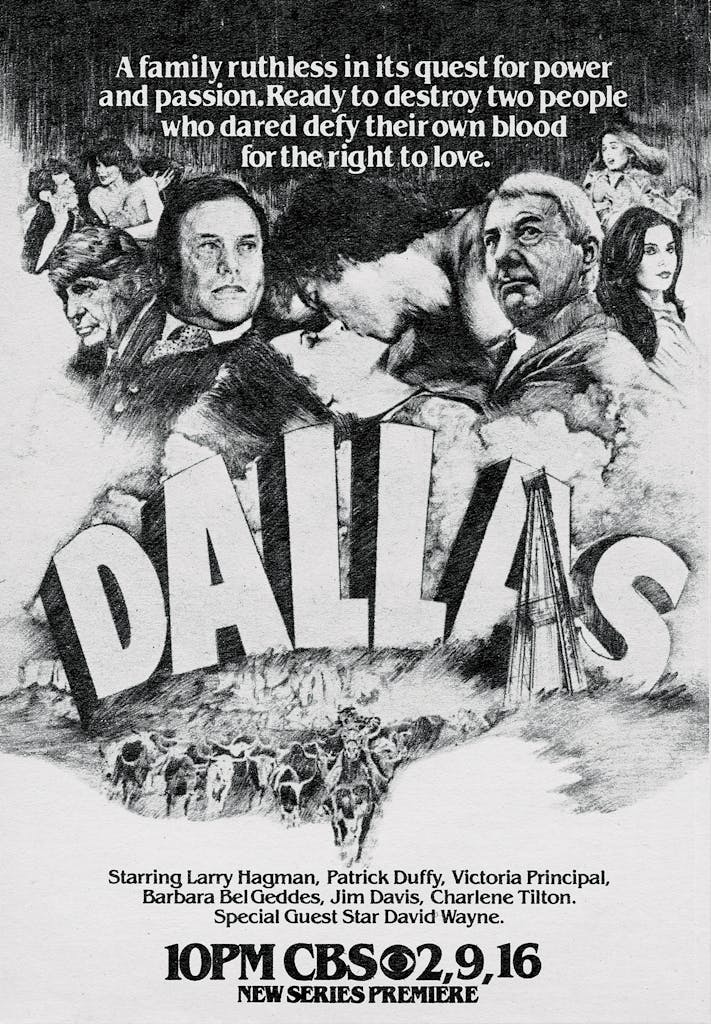

The production team wanted actors who looked attractive and wealthy and who had the chemistry for dynastic power games. Linda Evans passed on the show, and after weeks of auditions, they had the core cast: Patrick Duffy, the oft-shirtless “Man From Atlantis”; Victoria Principal, a veteran of numerous TV movies and TV series guest spots who also worked as a Hollywood agent; Jim Davis, who had been making westerns since the forties; Broadway doyenne Barbara Bel Geddes; seventeen-year-old Charlene Tilton, who was nearly homeless and got hired after sneaking into the casting sessions; Vietnam veteran Steve Kanaly, who had put together a decent film and television career after returning from the war; stage actor Ken Kercheval; and Linda Gray, a journeyman actor whose right leg was featured in the famous poster for The Graduate. In hindsight, the most essential decision was also the biggest wild card: Larry Hagman, the Weatherford native and son of Broadway icon Mary Martin. Hagman, who was then best known as the hapless Major Tony Nelson on the sixties sitcom I Dream of Jeannie, had spent the past decade playing bit parts and earning the moniker the Mad Monk of Malibu for his offbeat behavior.

Kristina Hagman is Larry Hagman’s daughter: When I started my first year of college, Dad said he couldn’t afford to send me to school. He was doing movies like The Big Bus and Mother, Jugs & Speed. My mother [Maj Axelsson] had to be very creative in figuring out ways to support our family so that Dad could continue to pursue his acting career.

Mary Crosby played J. R.’s sister-in-law Kristin Shepard: Maj was truly the power behind Larry. Before Larry got Dallas, Maj supported them as a contractor. She was an amazingly talented contractor. She designed hot tubs.

Kristina Hagman: He worked so hard on I Dream of Jeannie, and ultimately the stress took its toll. He went to see one of those psychiatrists—we’re talking late sixties, early seventies—who was using LSD as a drug for helping people out of depression. The psychiatrist cost, like, a hundred bucks. Dad felt like he was broke—Dad always felt like he was broke—and he said, “Wow, this stuff is great. I’m gonna get rid of the psychiatrist and just do [LSD].” So Dad had segued from uppers and cigarettes to mellow drugs like mushrooms and pot and wine. He embraced the zeitgeist of the era. He was high off his ass.

Michael Preece directed 62 episodes of Dallas: Larry drove what looked like an ice cream truck that had been converted into a motor home. It had a huge bubble inside, a skylight. Who drives one of those? He used to ride his motor scooter up and down the Pacific Coast Highway, dressed in full Indian gear.

David Jacobs: In my script, J. R. was bad, and he liked being bad. He was a guy who said, “You fuck them before they fuck you.” The part was offered to [the actor] Robert Foxworth, and on our first conference call with him, he asked us, “How are we going to sympathize with J. R.?” And I said, “We’re not. We’re going to hate him.” Foxworth passed. Then Barbara Miller, who was in charge of casting, suggested Larry. I knew he was a really good actor, but I still thought he was too soft. This wasn’t I Dream of Jeannie.

Kristina Hagman: Dad [who was raised mostly by his grandmother and mother in California and New York City] had done his last two years of high school in Weatherford, where his father lived. When he got there, he felt like a total fish out of water. He had the pompadour and New England–style clothes. His father took him for a crew cut right away. Went out shooting and hunting and drinking and swearing, and he felt completely at home for the first time since his grandma had died.

David Jacobs: The producers and I were waiting to meet with him, and then everybody looked up. I turned around, and Larry was holding his Stetson and wearing cowboy boots. And there he was.

The Dallas cast met for the first time in January 1978, during a script read-through at producer Leonard Katzman’s L.A. office. Hagman, in a fringed buckskin jacket, brought a leather saddlebag filled with champagne bottles. Duffy, a Buddhist who believes in reincarnation, met Hagman and thought, “This is my best friend’s hand I’m shaking, and it’s not the first time.” The room became less festive when the team discussed where the show would be filmed.

Steve Kanaly played Southfork Ranch foreman Ray Krebbs: After we all got our roles, they told us, “Well, we wanna shoot on actual location and go to Dallas. We think it’s gonna add a lot to the show.” I said, “Well, that’s a bunch of shit. This is January. Have you ever been to Dallas in the winter?”

Charlene Tilton played J. R.’s niece Lucy Ewing: We had eighteen inches of snow, which was unexpected. My hotel room door opened to the outside parking lot. It had a chain lock, but the lock on the doorknob was broken, so the door was blown open on the chain the whole time. I was seventeen—I didn’t want to bother anybody.

Victoria Principal played Pamela Barnes Ewing: We stayed at the Royal Coach Inn, otherwise known as the Royal Roach.

Charlene Tilton: One night a roach the size of a coffee cup ran across my chest.

Linda Gray played J. R.’s wife, Sue Ellen Ewing: All the men brought their wives and their children to Texas, and the wives would send them off in the morning with a kiss and a little cup of coffee. My kids were back in school in California with a lot of casseroles I’d made for them. I was totally pulled out of my life.

David Jacobs: When I got down there, I realized I’d really been writing Houston. Houston was the oil town; I didn’t know that Dallas was the banking town. But who wants to watch anything about Houston, anyway? That would be stupid. Still, when I thought about Dallas, I couldn’t get the Kennedy assassination out of my mind.

Patrick Duffy: When we were looking for locations to film in Dallas, it was almost a joke how many doors got slammed in our face. It was, “Hollywood? You’re going to bring up the assassination.” I think the city and the people were a little bit wary.

Mike Rhyner is a longtime Dallas radio personality: The “City of Hate” thing was very real at the time. That was a horrible, horrible, irremovable stain.

Linda Gray: My character had so little to do that they called me the Brunette on the Couch. So I went across the freeway to create Sue Ellen. I explored the world of rich Dallas people. In the ladies’ room at the Mansion on Turtle Creek, I looked down and watched this lady open her tiny Judith Leiber purse. Inside was a derringer and lipstick, that’s all. I said, “Excuse me, is that a gun?” And she looked at me like I was crazy. She said, “Yes. This is Texas.” And she continued to put on her lipstick and left.

David Jacobs: At the motel, when Linda would come in from her trips to Neiman Marcus, we’d look at the next day’s script and see how many lines we could take away from Victoria and give to her. Oh, God, those first months of filming were difficult.

Patrick Duffy: In retrospect, people like to think, “Yeah, I kind of knew it was going to be a hit.” We didn’t know it was going to be a hit.

Victoria Principal: They used to say it wouldn’t be a hit on the set. And I’d be thinking to myself, Nope, it’s a hit.

Steve Kanaly: My wife told me that she was pregnant. I was gonna call the kid Dallas, but my wife didn’t like that idea. She said, “It might not work out. Might not be a successful show. You might hate that name.” We didn’t call her Dallas.

A QUIET BEGINNING

The Dallas miniseries premiered on Sunday, April 2, 1978, with a bombastic earworm theme song. Helicopter shots of glittering towers, roving cattle, and oil derricks panned across the title sequence. The plots centered around Bobby, a reformed playboy in love, and Pamela, a reformer of playboys from the trailer park side of North Texas. The soap-operatic plots, fistfights at discos, and oilman villainy turned off some early viewers.

Jim Schutze was a columnist for the Dallas Times Herald from 1978 to 1991: Of course, Dallas hated Dallas at first. It was everything that Dallas felt that it was not. The boots, the hats, the ranching, the oil. That was all Houston.

Bob Miller was the show’s on-set men’s costumer: [When we shot scenes in downtown Dallas,] we had a whole stock of cowboy hats to give to the background actors, just to make sure Larry didn’t look odd. He didn’t want to be the only person walking around in a hat.

Steve Kanaly: In the beginning, I thought, “Well, this is obviously not gonna go, because it’s too different. There’s nothing like this on television.”

Matt Zoller Seitz: It had all the soap opera elements that had traditionally drawn an audience of women, but it had also evolved from the western. Except in a western, the heroes are often humble homesteaders trying to start a new life. In Dallas, the heroes are the businesspeople who are trying to take the humble homesteaders’ land away.

Steve Kanaly: The characters had real wild story lines. Ray Krebbs starts off as a pedophile, having a time with Lucy in the hayloft. Oh, my gosh.

Charlene Tilton: My character, Lucy, was pitched to me as “a manipulative little sexpot, born with a silver spoon in her mouth. Has her granddaddy, Jock, wrapped around her finger. A real spoiled brat.”

Linda Gray: When we were filming the miniseries, I’d be sitting on the couch, with no voice, and I’d look at J. R. and think, Look at this idiot. Who would be stupid enough to marry him? I started creating Sue Ellen in my own mind. I thought, She’s gotta have a few problems of her own; she’s got to chase him. And while they filmed other characters, Larry and I would have these little fights in the background. He’d tell me to sew his buttons, and I’d say, “I don’t sew buttons,” whatever. When the miniseries aired, CBS noticed Larry and me in the background, and they said, “What’s happening over there?”

Although the miniseries was initially received with little fanfare, the fifth and last episode,“Barbecue,” was the eleventh-most-watched show of the week. Dallas was picked up as a series. In line with Jacobs’s original concept, the producers changed the plot structure from self-contained episodes to ongoing story lines. In its first full year, things changed. Exterior filming moved from a ranch in Frisco to a ranch in Parker, outside Plano; the show continued to climb in the ratings; Jacobs left for Knots Landing (a Dallas spin-off based on Jacobs’s original Ingmar Bergman–style pitch); and Hagman and Katzman took charge.

Joe Duncan owned the ranch in Parker that was chosen as the site of Southfork: I was mowing the front pasture, and a guy pulled up in a pickup truck. He said, “We think we’ve got a script that would fit your ranch. The producer and director will be in town Tuesday.” Leonard Katzman showed up on Tuesday. Great guy. He said, “We’re rolling the dice on this thing. CBS is backing us, but the chances of Dallas becoming a hit are remote. Highly remote.”

David Jacobs: It quickly became much more Leonard Katzman’s show. I was the birth mother, but I only wrote two more episodes after those first episodes, and one of them was the one that kicked off Knots Landing.

David Paulsen: When Dallas became a hit, in its first full season [September 1978 to March 1979], CBS came to David and said, “Well, you got anything else?” He left to make Knots Landing, and with Leonard, the Dallas structure continued to evolve from Romeo and Juliet. He was writing J. R. against Bobby, he was writing J. R. against Cliff [Barnes], he was writing J. R. against Sue Ellen. I don’t want to get too terribly personal . . . but you write about your own relationships.

Sheree J. Wilson played J. R.’s cousin-in-law April Stevens Ewing: I loved Lenny. He took the drama from his family circumstances and put them into the stories. The show was a soap opera, but sometimes art imitates life.

Patrick Duffy: He had troubled children who have since found themselves. They would all come to Dallas, and people on set would say, “Oh, did you hear what happened last night?” He had that in his personal life, and I’m sure it influenced the show.

Michael Preece: I asked Leonard where he got all these stories, and he said, “I get it from my family and your family and other people. David Paulsen’s family. You know, all the problems we have with our kids.”

Patrick Duffy: Leonard was the only person who scared Haggy. Larry was cock of the walk, but when Leonard walked on the set, Larry would say, “Good morning, Mr. Katzman.” It was Larry’s military school training. Leonard very seldom raised his voice, very seldom was authoritarian on set, but he carried that authority.

Michael Preece: When Katzman wasn’t there, the boys [Duffy and Hagman] did terrible pranks all day long.

Victoria Principal: In one scene, as often happened, Bobby and Pam began making love under the covers. As Patrick moved in to take me into his arms, something enormous and very hard pressed up against my pelvis. I screamed. I had no prior point of reference to anything this big or this hard. It turns out Patrick had talked the prop man into hiding, at the end of the bed, a plastic mannequin’s leg. They could hear me scream in the next state, because I really believed it was attached to Patrick’s body.

Mary Crosby: On literally my first day, I’m coming out of the Southfork pool in the world’s smallest bikini, and I’m looking up at Larry. I’m supposed to be drying myself off seductively, but I’m kind of terrified, and I have the towel clutched to my breast. The director says, “Cut—let’s do this again.” I go back in the pool, and I look up, and Larry has his eyes crossed. He’s drooling out of the side of his mouth, and he’s put a banana down his pants. I realized everything was going to be okay. Larry just took the best care of everybody.

Patrick Duffy: By the time the show became a hit and Larry became the star, he set the tempo and the atmosphere. And we followed. If the show would have gone on as predicted—Romeo and Juliet, Bobby and Pam—it wouldn’t have lasted but a couple of seasons.

Kristina Hagman: Dad made notes in his scripts, and anytime it would say, “. . . and J. R. gets his rival and beats him to the deal. He sneers,” Dad would just turn it into a smile and a giggle. And not only would he get the deal, but he would somehow frame his enemy in some sex scandal.

Matt Zoller Seitz: It’s very difficult to imagine that the guy who was on I Dream of Jeannie could’ve been capable of this. It’s really an astounding transformation. I mean, Hagman was comically bumbling around—dealing with the shenanigans of this genie in a bottle—and then, a mere decade later, he’s ordering people’s ruination. I was talking to a friend about Dallas, and he said, “Who knew that Major Nelson could be such a dick?”

Linda Gray: At first, men viewers were like, “A nighttime soap opera? I can’t watch that, are you kidding?” And then they started peeking in. “What is she watching?” They loved the business, and the conniving J. R. was either them or he was their boss or he was somebody else they knew. And that’s when the groundswell started.

Charlene Tilton: I remember when the network moved us from Sunday to Friday. Jim Davis said, “Well, I just think this might work out.” I don’t know why he said that or how he knew, because nobody watched TV on Friday nights.

Linda Gray: There was a recession, and on Friday nights people couldn’t afford to pay babysitters or go out. After a week of work, a lot of people were just done, and they wanted a little frivolous television.

“WHO SHOT J. R.?”

As the team worked on the third season’s ending, a CBS executive called Katzman. “We have good news and bad news,” he reportedly said. “The good news is that you have to shoot four more episodes this season. The bad news is that you have to shoot four more episodes this season.” Having already written what they thought were the final episodes of the season, which featured a deathbed murder confession, a paternity suit, and an attempt to return Sue Ellen to a sanitarium, the writers struggled to find a cliff-hanger with ample bombast. After some debate, someone said, “Why don’t we just shoot the bastard?”

On March 21, 1980, “A House Divided” aired. A few minutes before 10 p.m. Central Standard Time, millions watched J. R. work late at his desk, answer a ringing phone only to be greeted by silence on the other end, get up to refill his coffee mug, hear footsteps down the hall, take two gunshots to the stomach, and fall to the floor as the credits start to roll. The CBS marketing department soon launched a promotional campaign built around the tagline “Who Shot J. R.?” and America—and a good chunk of the rest of the world—lost its mind.

David Paulsen: One writer, I don’t remember who, said, “Well, why don’t we shoot J. R.?” “All right, why not.” It was as simple as that, and he was shot.

Mary Crosby: On the set, everybody got to shoot J. R., including the producers, including Larry, including the makeup artists, the continuity people. Everybody got to shoot him because they wanted the actual shooter to be kept a secret.

David Paulsen: We had no idea who shot him. The producers just put a gun in the hands of many people, and Katzman would figure out later who it was.

Charlene Tilton: Irving [J. Moore], who was directing the episode, said, “Hey, Charlene. Come here, hold this gun, and say, ‘Take that, you schmuck!’ ” And right then, I knew I didn’t shoot J. R., because Lucy would never use the word “schmuck.”

Matt Zoller Seitz: They did that cliff-hanger ending. For three months, me and my friends were out of school, and we’re wondering who the hell killed J. R. Ewing. Everybody was wondering.

Kathryn Siefker helped organize the Bob Bullock Texas State History Museum’s 2008 Dallas retrospective: There was the natural summer break, and then the 1980 Screen Actors Guild strike [which pushed the airdate of the season-four premiere back to November]. Next thing you know, Dallas was everywhere.

Joe Duncan II is Joe Duncan’s son, who lived on Southfork Ranch: People started showing up at our front gate. This was before we opened our gates to tourists. They were chipping away the fence, they were picking up rocks, glass, anything they could get their hands on. It was nuts. I once was twenty feet away from a guy who jumped the fence and went out into the pasture to pick up a piece of horse manure to take home as a souvenir. People would take whatever they could get their hands on.

David Paulsen: One of the stars, I forget who, called Leonard Katzman and said, “Listen, I’m on the golf links with ex-president Ford. He wants to know who shot J. R.” Leonard said, “Can’t tell him,” and he said, “Hang on just a minute.” He went off the line. He got back on the line, and he said, “Len, he said to tell you that he used to be president of the United States. He can keep a secret.” Leonard said, “I can’t tell him.”

Mary Crosby: I was filming a miniseries in England, where shops across the country literally closed up just so people could watch Dallas. Some guy who sold munitions to Third World countries offered me a million dollars to tell him who shot J. R.

David Paulsen: Yeah, the world went into pandemonium. There was a sense of “Oh, my god, the show’s going to be over.” Larry was renegotiating his contract at the time, so there was no sense of, “We know he’ll be back.” Nope. We did not know if he would be back or not.

The cover story of the April 14, 1980, issue of People began, “Not since John Milton gave Satan all the good lines in Paradise Lost has a villain so appalled—and fascinated—the world . . . The only remaining question is whether the J. R. character will crawl back to his feet for revenge next season, or was that gun loaded with wolfsbane and silver bullets? Hagman just chortles that the shooting was a ‘contract’ job. ‘Whether I live or die will depend upon my contract negotiations.’ ”

Steve Kanaly: This is a good story. Carroll O’Connor [who played Archie Bunker in All in the Family] was close friends with Larry. He said, “Well, Hagman, you know what CBS has done by shooting you. If you’re ever gonna hold ’em up, now’s the time. You oughta just disappear and tell ’em what you want.” So he did.

Sheree J. Wilson: CBS hadn’t decided yet if J. R. was going to be alive or if he was going to be dead. Maj grabbed Larry’s publicist and said, “Larry, we’re going to New York.” And so they flew to New York, and they went to every major party there was. They went to the Whitney, they went here, they went there, and they made sure CBS saw all the publicity. And then they went to London, and they went to all the London parties. They met the Queen, and they made sure the press got back to CBS.

Kristina Hagman: My dad was at a Royal Variety Performance, and the Queen Mother went up to him and asked, “Can you tell me who shot J. R.?” And he said, “Not even for you, Mum.” We went to Monaco, and we’re having tea with Princess Grace. It was like all doors were opened. We could go anywhere.

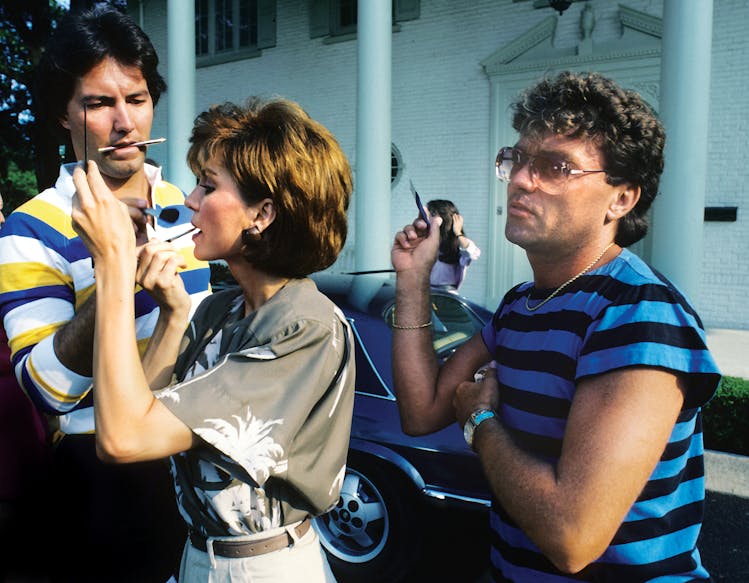

Bob Miller: The cast and crew arrived in Dallas during a heat wave that never got below 100 degrees for thirty days. Larry had not signed his contract yet. We shot his scenes in two different ways: we filmed someone with the same haircut facing the opposite direction, and we shot it with a man bandaged up, like he’d been bludgeoned, so that they could bring on another actor after the character had reconstructive surgery on his face.

Patrick Duffy: We would talk on the phone. I said, “Larry, they’ve got this guy’s face wrapped up. They’re going to cave.” He just goes, “Yeah, I know.” He was ready to go to work, but he knew he had them by the balls.

Kristina Hagman: At least in his conversations with the press, Dad would distance himself from the J. R. character. He wanted everybody to know that he was a nice guy. But in truth, it wasn’t all that different. Dad loved secrets, and he was very good at deals. Only after his death did I realize that he had had multiple affairs. That’s a very J. R. kind of thing.

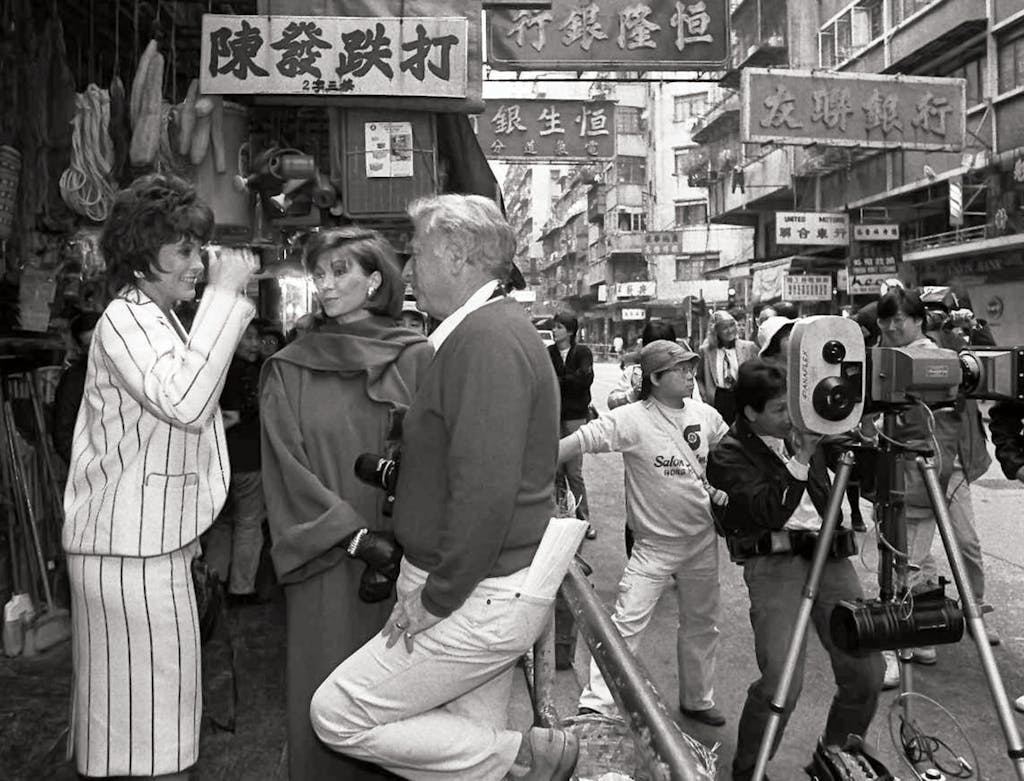

DALLAS GOES GLOBAL

After months of bargaining with Hagman’s lawyers—who wore white cowboy hats to the negotiations—CBS caved. They agreed to pay Hagman $100,000 per episode, an astonishing sum at the time. Hagman took a flight from the Caribbean and helicoptered straight to the Southfork pool. Then, on November 21, 1980, “Who Done It?” aired, wrapping up the “Who Shot J. R.?” mystery with a reveal of the killer that was widely regarded as disappointing. Even so, the episode was watched by hundreds of millions of people across the world, reportedly setting viewing records domestically and globally. Dallas became the number one show in the U.S., and Dallas mania was in full swing internationally. In fact, the series was the only American show to air at the time in Romania, where, Hagman and Duffy later claimed, its alluring portrait of capitalism helped discredit the Communist government.

Matt Zoller Seitz: I remember being shocked and thinking it was kind of ludicrous and anticlimactic when they revealed who did it.

David Paulsen: To decide who shot J. R., we needed someone who was a natural choice in terms of plot and was expendable to us at the time.

Mary Crosby: Larry knew that I’d shot J. R. way before I did, and at one point, he pulled me aside and said, “Darling, you know, you might want to get a publicist and be ready for insanity.”

Harry Hurt III was a senior editor at Texas Monthly and a close friend of Larry Hagman’s: More Americans watched the “Who Done It?” episode than voted for Carter and Reagan, combined. That’s when the show became a truly global phenomenon.

Ien Ang is a cultural studies professor and the author of the academic book Watching Dallas, which was published in 1985: The show became more than its huge ratings. Jack Lang, the French minister of culture at the time, said something like, “Dallas is the epitome of American cultural imperialism.”

David Paulsen: Lenny and I were invited to Paris in hopes that I would come up with some kind of French version of Dallas. Notwithstanding his publicly professed dislike of American culture, Jack Lang tried his damnedest to meet us. Schedules didn’t permit it, but Len and I were invited to the Élysée Palace, where we met several of President Mitterrand’s cabinet people.

Matt Zoller Seitz: I’ve always wondered about how people in other countries perceived Dallas, beyond the fact that it was an entertaining show. Were they watching it because they found the characters relatable, or were they watching it because it was essentially, in their minds, a black comedy about a bunch of capitalist pigs in cowboy hats?

Audrey Landers played Lucy’s sister-in-law Afton Cooper: Before the Berlin Wall fell, I did a film that was a cooperation between Eastern Bloc countries and Western countries. I met with the minister of culture and tourism of East Germany, and he and his comrades couldn’t grasp the fact that Dallas was in existence. They just were appalled by it. It was blocked in East Germany unless you were right at the border.

Kristina Hagman: Leaders in Romania allowed Dallas to be aired because they thought it would show the downside of [capitalism]. Instead, I meet people from the former Soviet Bloc who say, “Dallas inspired me to leave. It inspired me to go out and become rich.”

Charlene Tilton: I went to Cape Town to do an appearance at a shopping mall. My manager told the mall people that he was worried about security, but they said, “We had Richard Burton and Elizabeth Taylor two months ago, and five thousand people came. Believe us, we’re ready.” We go to the mall, and there are ten thousand people. Pandemonium. Part of the mall’s upper level, something collapsed up there, and there were people jumping on our car.

Patrick Duffy: My wife and I went to see da Vinci’s The Last Supper, in Milan. I’m standing there, in a group of people, and while I’m looking at it, Carlyn taps my shoulder. She goes, “Look around.” I do, and nobody’s looking at The Last Supper—everybody’s looking at me. And I think, “Oh, my God. I get it now.”

As Dallas went global and high-priced oil and cheap loans brought people and construction cranes to town, the word “Dallas” took on a new meaning. The show was both a cause and an effect of this new atmosphere, and the city began to enjoy its reinvention.

Jim Schutze: The parties and society photographer for the Dallas Times Herald was shooting the Crystal Charity Ball one night, and he called me and said, “Schutze, you’re not gonna believe it. People are showing up in cowboy boots. They are dressing like they’re on the show.”

Matt Zoller Seitz: For people in the city, this larger-than-life fable was enormously exciting. You’d get home and turn on this TV show called Dallas, and you see all these attractive, powerful people driving fancy cars, wearing fabulous clothes, having great sex, throwing lots of cash around, and it kind of makes you feel honored to live in Dallas. “Oh, apparently this is where the exciting people live.”

Jim Schutze: Many big American cities have some emblem to define themselves by. Detroit: cars. San Francisco: bay, harbor, gold. Dallas: what? Insurance? “I come from the insurance town. What do you think of that?” The show was absolutely filling the void.

Susan Howard played Ray’s wife, Donna Culver Krebbs: All of a sudden, we’ve been forgiven. We’re the place that killed JFK. And we didn’t do it, okay? A crazy human being did it. But that stigma remained. And then, suddenly, Texas is where everybody wanted to go. They wanted to see the Cowboys, they wanted to see Southfork. And it was like all that stuff just washed away. It was over, it was gone, and we were forgiven. And I loved that.

Jim Schutze: I really think Dallas looked at Dallas and thought, “Okay, as a medallion we can hang around our necks, this is way better than the assassination. City of Hate versus City of Greed? We’ll take greed.”

Patrick Duffy: Greed, lust, and avarice.

Michael Cain is a Dallas filmmaker and was a friend of Larry Hagman’s: There was this deep confluence of events in Dallas. You had the price of oil doubling per barrel. You had Neiman Marcus and [the real estate developer] Trammell Crow. You had S&Ls giving out money freely, and there was no penalty to be paid at first. Wealth, glamour, and decadence—the idea that more is more, that nobody is small by choice—the eighties pointed toward the city of Dallas.

Joe Duncan: The Midwest was [having economic troubles], and people would visit Southfork and ask me about taxes here. Next thing you know, they’d be here. One guy moved right down the street to be close to Southfork.

David Paulsen: You could see the difference very quickly. If you look at the original Dallas title sequence, there’s only a handful of buildings downtown. When we changed the intro [in season eight], all these buildings had suddenly gone up.

For the next four seasons, Dallas finished every year ranked either first or second in the national ratings. The set was so smoothly run that the cast and crew called it “director-proof.” The plot formula was so sturdy that Paulsen said the writers could spend their time trying to make each other “piss on the floor with laughter.” And nearly all the actors and crew, some of whom were becoming uncommonly close with one another, said they had a lot of time to enjoy themselves. People weren’t shy about partaking of the many bottles of champagne that were used as props in the show.

Michael Preece: It was a dream job. People would be saying, “Wait a minute. I’ve had three glasses of champagne, and it’s not even 8:15 a.m.”

Roger Phillips was a lifelong friend of Larry Hagman’s: When Larry would drive to the set in his van at six o’clock in the morning, he would have an open bottle of champagne and a glass between the seats.

Patrick Duffy: My wife would always laugh because I would leave for work an hour early every day. I never had a single bad day on set.

Michael Preece: I’m not saying we were bored, but we had a lot of time on our hands. We’d set up things in the background that nobody would see unless they were a real student of background action. At a party scene, we would have a young 17- or 18-year-old guy—usually some friend or relative of one of the cast or crew—making out with a 75-year-old woman.

Linda Gray: I was divorced by then, and Larry, Maj, and I would run around to Bali and Australia and other places. I would flirt with people and have a great time, and Larry would act like a protective brother. He’d say, “This is totally unacceptable,” and I’d just smile at him and keep going, whatever I was doing.

Michael Cain: Somebody in Dallas came up to Larry and said, “There’s this nightclub called the Starck Club, and you’ve got to go.” Larry brought a group of people, and his mind was blown. It had the most beautiful people, and the bartenders sold MDMA in books of matches. Larry stayed out very late that night, and he had to be on set at 5 a.m. On set, a policeman came up to him and said, “You cost the city a lot of money last night. Eighty officers were ready to raid the Starck Club, and when you walked into the club, we had to shut the raid down.”

Michael Preece: A lot of the crew were doing coke. I never saw Patrick smoke grass or anything, though. Larry, but not Patrick.

Johnny Lee is a country singer from Texas who was married to Charlene Tilton from 1982 to 1984: It was definitely the era of cocaine back then. Hell, we didn’t know any better.

Harry Hurt III: The party rumors are all pretty true. Those were the days, young man.

Michael Preece: We’d go through a dozen bottles of champagne. Larry’s gone now, so I can tell you this: he was better in the morning. In the afternoon—he’d had too much.

DECLINE AND FALL

As the show entered its later seasons, the TV landscape got crowded with Dallas semi-impostors. Robert Foxworth, who had turned down the J. R. role years earlier, got to star in one of them, Falcon Crest. The most successful of them, Dynasty, turned the Southfork formula up to eleven. It had more jewels, bigger mansions, four-minute catfights, and a cliff-hanger involving a terrorist attack on a royal wedding held in the fictional European nation of Moldavia. In response, Dallas ratcheted up the eighties camp, delving into outlandish plots about international intrigue and relegating its female characters to lame story arcs. With chances to capitalize on their fame elsewhere, some of the show’s stars decided to leave. As often happens to prime-time shows nearing their double-digit birthdays, Dallas began to lose millions of viewers.

Linda Gray: My shoulder pads were so big, literally, that one time I wondered, “Am I going to get through that door?”

Chris Baker is the founder of the fan site Dallas Decoder: The show definitely takes a campy turn. Part of me thinks it’s fun seeing Sue Ellen come downstairs in a flowing dress and a designer turban to go to the movies. But another part of me thinks, “Eh, it’s not quite right.”

David Paulsen: It got worse when Patrick left the show [in 1985]. You lost the major structural support. We could lose Lucy, that wasn’t huge. We could lose Donna. But to lose Abel: What do you have for Cain to do?

Steve Kanaly: I cried when Patrick left. He died in the story, but those were real tears. He wanted to go out and be in the movies. I told him, “It’s not what you think out there.”

Patrick Duffy: I did a small part on [the TV movie] Alice in Wonderland. I played a goat. And Larry came to the makeup room while I’m being made up as a goat, and he just looked at me and said, “Aren’t you proud of the decisions you’ve made?” A little while later, while I was on set, he put a live goat in my dressing room.

Linda Gray: People like to see the family unit together. No matter how crazy, how dysfunctional, how whacked-out they are, I think they love that unit. When family members start leaving, it makes them nervous.

Patrick Duffy: Leonard comes to my living room and says, “Here’s my plan. I don’t like the way the show’s been going—off into international drug cartels and exotic things. It’s not Dallas. So I want to get rid of the whole season. I want it to be a dream, and you never die.”

David Jacobs: [Sighing] “The Dream Season” . . .

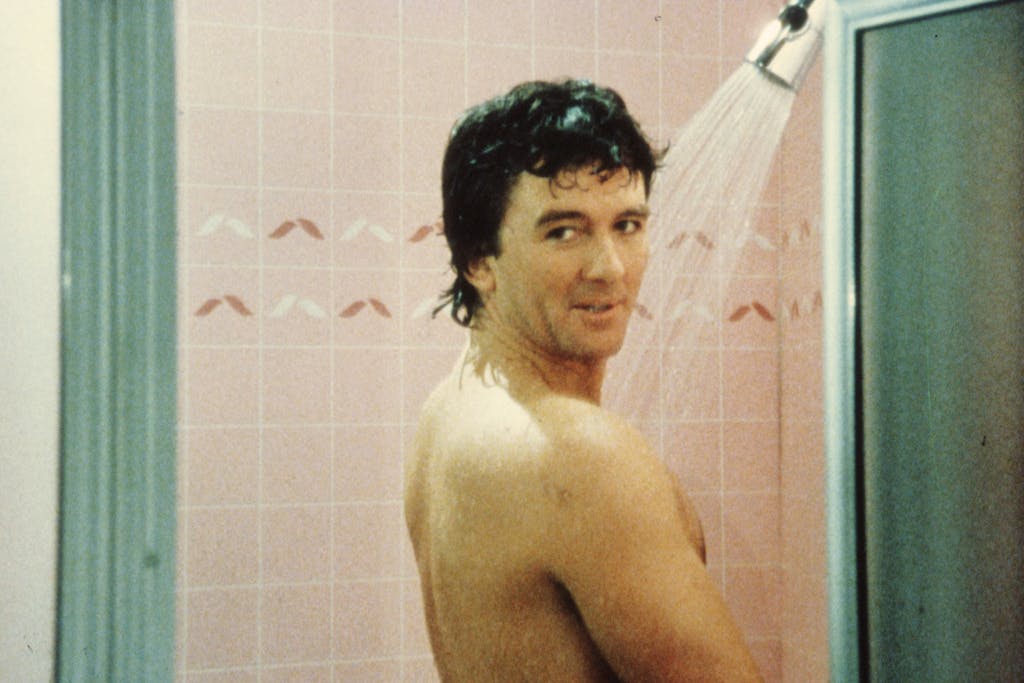

Patrick Duffy: We couldn’t let anyone [in the cast or crew] know [I was coming back]. So Leonard went to a commercial production company and said, “Colgate-Palmolive wants to do an Irish Spring commercial with Patrick Duffy.” [But, unbeknownst to them, we were really filming a scene for Dallas.] In the “commercial,” the shower door opens, and I turn around and go, “Good morning.” Beat, beat, beat. “And you can have a good morning too, if you wake up like the Duffy family with Irish Spring.” The commercial crew didn’t realize it, but they’d built an exact replica of Pamela’s shower from the show.

Victoria Principal: I didn’t find out until I watched [the season nine finale] live. There was supposed to be a scene in the middle of the episode when my character wakes up, and then John Beck [who played Pam Ewing’s suitor Mark Graison] tells me “Good morning” from the shower. But it wasn’t there. And then, in the final scene, my character wakes up, and it’s Patrick in the shower. I called him and started screaming. “How could you not tell me? Oh, my God, you’re back!”

Patrick Duffy: A good number of our audience was upset. They felt cheated. And I understand that, because if we went to international drug cartels, they went with us. And when they were told, “Well, that didn’t really happen,” they went, “Uh . . .”

Charlene Tilton: Well, you know, at some point, the show . . . it changed, didn’t it?

Victoria Principal: Here’s what happened. The show became so successful that everyone at the top, the showrunners, who were all men, and those who ran the network, who were all men, did not want to risk the formula that they felt was working. More and more of the emphasis was on men, and the women became more and more secondary. It was very frustrating to me as an actress, as a person, as a woman. I don’t know why anyone was surprised that I left [in 1987].

Steve Kanaly: I never saw it as a guy’s show, although there was a certain exploitation of the women. Putting them in all these elaborate gowns all the time, J. R.’s sexual conquests all the time—it’s all sort of anti-women, from today’s perspective.

Patrick Duffy: The women characters in some ways were the driving force, but yeah, it was written as a guy’s show. Leonard was quite misogynistic when it came to that.

Linda Gray: When I was renegotiating my contract for seasons nine and ten, I went into Leonard’s office and told him I didn’t want any more money; I only wanted to direct one episode. And even though I’d been studying with [French director] Lilyan Chauvin, and even though Larry and Patrick had directed plenty, Leonard said he’d rather fire me than have me direct. His reasoning was that “if Linda gets to direct, then the other women will want to direct too.”

Victoria Principal: I once came to a producer to point out a continuity error that left a giant hole in a story. And he reached out, petted me, and said, “Don’t worry your pretty little head about it.” And I turned and said, “If you ever do that again, you will lose your arm.”

Linda Gray: We were just bookends. We were reactors to what the men did. “He did that, therefore I’m going to do this” or “I’m going to have an affair” or “I’m going to start drinking again,” and that’s what I found really boring after a while.

David Jacobs: I never stopped thinking of Dallas as mine, but toward the end, I didn’t like the ways I was thinking about it. Eventually I wasn’t even watching it anymore.

On May 3, 1991, Dallas aired its two-hour series finale, in which a drunken and financially ruined J. R. is visited by an angel who reveals to him an It’s a Wonderful Life–style alternate family history of the Ewings without him. Having outlasted Dynasty and the Reagan presidency, the show continued via occasional TV movies of the week, reunion specials, and a short-lived 2012 reboot on TNT. After the new series began, Larry Hagman—seventeen years after surviving liver cancer and after learning that he had stage II throat cancer—was diagnosed with leukemia.

Patrick Duffy: Larry told me, “You know, I’m not worried about dying. I’ve taken so many magic mushrooms, I know what’s on the other side.”

Linda Gray: I was the big sister, because I was always telling Larry what to do. Well, mainly what not to do. “Don’t do that” and “You know you can’t eat that” and “Stop drinking like that!” Blah blah blah. He rebelled, but somebody needed to be his minder, because he was a party. His job on the planet was to bring joy, no matter where he went.

Patrick Duffy: He was doing a lot of cancer therapy stuff. Linda had a mentality of “No, you can beat this,” because that’s who Linda is. Larry would wait until she was gone and then have a glass of wine.

Kristina Hagman: He was on the Dallas set Tuesday, and he passed away Friday. Given the circumstances, he got to go out in high style, doing the work he loved, surrounded by those he really enjoyed. It was my brother, another dear friend, and Patrick and Linda who were there with him when he stopped breathing.

Harry Hurt III: Larry was the best friend anybody could ever have. He arrived at my wedding dressed up in a white naval uniform with a white sailor’s cap, and he brought me, as a wedding present, a crystal baby bottle filled with Mendocino County Thunder Fuck [a potent strain of marijuana].

Sheree J. Wilson: I got married at Larry’s house, and he walked me down the aisle.

Bob Miller: Larry was such a giving person. This makeup artist was getting married, and her parents weren’t at the wedding, and Larry had the wedding at his house and gave her away.

Mary Crosby: I have to say, the best thing about my time on Dallas, far more than being the answer to the “Who Shot J. R.?” trivia question, is that I had a deep and loving lifelong relationship with Larry and Maj. Larry walked me down the aisle. The Dallas family continued, with or without the show.

Patrick Duffy: I can’t think of him and not smile. People go, “Oh, it must be hard.” I’m like, well, I miss my friend. But every time I think of him, I just go . . . It’s the best time I ever had.

WHAT DID IT ALL MEAN?

On March 30, 2018, the show marked its fortieth anniversary with a reunion at Southfork. Dallas fans came to North Texas to pay tribute and to shake hands with many of the show’s remaining stars. Four decades later, the Dallas skyline is still filled with cranes, and even our highest-brow conversations are filled with references to serial TV dramas. If all debts were paid, the city of Dallas and HBO would send royalty checks to the trashy, campy Ewing family.

Charlene Tilton: At the fortieth anniversary, Steve said, “We’re gonna have a game. Let’s see which fan came here from the farthest distance.” We had people from Dubai, Wales, Romania, South Africa, Egypt, everywhere.

Caryl Knapp is a tour guide at Southfork: The country that the most visitors come from these days is Bangladesh. [The show’s airing] was delayed there, so they’re just getting the [2012] reboot now. They’ll come here at ten, twelve a clip, and I’ll ask them questions about the show—I ask a lot of questions—and they’re right on it.

Andrew Litton was the music director of the Dallas Symphony Orchestra from 1994 to 2006: When the Dallas Symphony made its debut at the Proms—a festival in London’s Royal Albert Hall that’s been going on since the late 1800s—I thought, “If we deserve a third encore, we’ll trot out the Dallas theme song.” The musicians were up in arms: “Oh, come on, Andrew. You’re from New York; you don’t understand. We’ve tried to divorce ourselves from this TV show forever. We want to be more upmarket than that.” I had to listen to them individually and in committees; it was almost like Groundhog Day: “Mr. Litton, forgive me for bothering you, but is there any way I can get you to reconsider?” And I kept saying, “Trust me, trust me, trust me.” My ex-wife, Jayne, grew up in England, and she’d told me Dallas was so popular when she was in college that they used to fight for who got the seats by the TV. So I knew we’d be fine. And after two encores, we play those first chords, and the audience goes absolutely crazy. Stomping, screaming, waving American flags. The British press wrote about it for a year.

Ron Kirk was the mayor of Dallas from 1995 to 2002: Having had the privilege to represent Dallas around the world, it was at best amusing and at worst somewhat disheartening how, just about every country we went to, if I did an interview on a local TV show, it’d open with two film clips: the footage of the Zapruder film and the theme song from Dallas.

Jay Marshall is the father of this piece’s author: Son, don’t forget that, even today, three things shape how the world sees our city: the assassination, the Cowboys, and Dallas.

Mike Rhyner: Your dad gave you some good advice there.

Victoria Principal: For years after I left Dallas, I suffered from a kind of survivor’s guilt. I felt like I had helped perpetuate this idea that more is better, that wealth is the end-all, and that Dallas was the home of the “Greed is good” mind-set. Money is a wonderful servant but a terrible master, and the theme of Dallas was just the opposite.

Matt Zoller Seitz: This was the era when the last remnants of the counterculture were being snuffed out. The idea of political change had seemed to come to a somewhat ignominious end. The Who lyric—“Meet the new boss / Same as the old boss”—I think it planted itself in a lot of people’s minds. It was all, “Let’s have fun. Let’s dance. Let’s go to the beach, if we have one. Let’s drive around in our giant American cars and get laid and just not worry about it.”

Leigh McCloskey played Lucy’s husband, Mitch Cooper: I felt a shift, as an actor, from the seventies to Dallas. Things went into pastel. They weren’t making Dawn: Portrait of a Teenage Runaway in the eighties. It went away from getting into cultural problems and much more into Fantasy Island, The Love Boat. It was, “We are going to build a prettier picture.”

Audrey Landers: I think Dallas just represents an exaggerated, fictionalized American dream. We certainly were not politically correct, as far as modern times go, but look at the characters. It was a lesson that money doesn’t buy happiness.

Victoria Principal: The scripts were so brave the first five years, whether it was about breast cancer, homosexuality, alcoholism, miscarriages, or wealth and how it can breed discontent. So now, in 2018, I look back and feel that the aspects of Dallas that were groundbreaking outweigh the greed.

Chris Baker: It paved the way for so much of the great television that everyone is obsessed with today.

Matt Zoller Seitz: You can draw a straight line from J. R. Ewing to Tony Soprano to Walter White. I mean, what is Game of Thrones but Dallas with dragons?

Chris Baker: David Jacobs’s greatest contribution is the idea that prime-time television story lines don’t have to end each week. Pretty much every show ends its seasons with cliff-hangers now.

Matt Zoller Seitz: Even if people have never seen an episode, they probably have an idea of what Dallas was. And they’re not wrong. If you say, “Oh, my God, I feel like I’m in an episode of Dallas,” people know what that means. It means that there’s some secret puppet master pulling the strings, and you haven’t figured out who it is yet, but he’s out there somewhere—and he’s probably wearing a cowboy hat and smiling.

The quotes in this story have been edited for clarity and length.

Max Marshall is a writer based in Brooklyn and Dallas. He recently completed a Princeton in Asia journalism fellowship in Hanoi, Vietnam.