Marie, the narrator of Merritt Tierce’s novel Love Me Back (Doubleday), is a Dallas waitress with an edge—and an eye—as sharp as the box cutter she uses to methodically slice her thighs. Valedictorian of her exurban high school, Marie got knocked up on a church mission to Mexico at the end of her senior year and “married my daughter’s dad when I was seventeen because my own dad hit me for the first and only time. Whacked the side of my head and said we needed to plan a wedding before I started showing.” The day after she and her husband celebrate their first anniversary with their infant daughter at a Macaroni Grill in Lewisville, she starts cheating with a spiky-haired co-worker whose chest is tattooed with “the face of a pit bull he said was the best friend he’d ever had.” An adulterous cuddle with another colleague is spoiled when Marie’s lactating breasts spontaneously shower him with milk. Soon she leaves the shotgun marriage behind “like a snake molting out of a skin . . . slithering away cold-blooded.” And that’s just a brief introduction to one of the most mesmerizing heroines in recent fiction, a self-destructive naïf who embodies the plight of millions of underemployed and overworked single mothers—and whose compulsively readable tale threatens to drag Texas literature kicking and screaming into the twenty-first century.

Love Me Back is a highly autobiographical first novel; now living in Denton, Tierce was herself a teenage mother who soon became a single mom and supported her family waitressing at Dallas restaurants. Although Tierce subsequently acquired a pedigree that screams “literary fiction”—a master’s degree in creative writing from the University of Iowa’s highly regarded program and a couple of prestigious young-writer awards for her stories—her debut novel has a working-class authenticity that can’t be picked up in writing workshops.

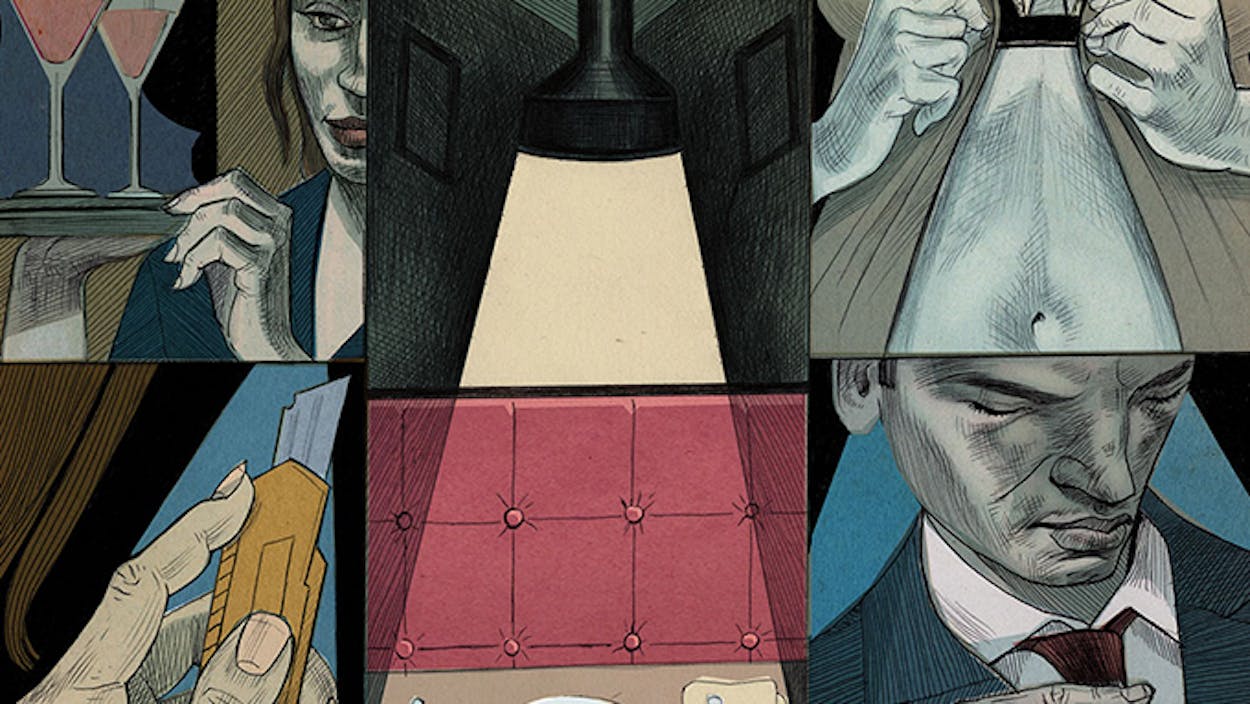

Neither can her prose style, a pugilistic minimalism that doesn’t much resemble the rambling, neo-Dickensian narratives currently enjoying critical acclaim. Love Me Back is essentially a collection of stories inspired by Tierce’s own restaurant experiences, loosely stitched together by Marie’s progression from franchise flunky to luxury steakhouse dominatrix. But along the way, riffing with stinging insight on the same sort of social and economic inequities from which Dickens himself constructed his elaborate plots, Tierce gives this slim volume the heft of a career-making breakout book.

Marie’s less promising career begins at the Olive Garden. As hardworking as she is bright, she moves steadily up the food chain—Chili’s, then Dallas’s Dream Café (also a real restaurant)—and is soon dishing us Zen and the Art of Waiting Tables maxims: “Whatever you skip in your prep will be the one thing you need when you’re buried. If you look at the stack of kids’ cups while you’re tying on your apron in the afternoon and decide there will probably be enough for the night . . . eight soccer teams will come in at nine.”

One of the Dream regulars owns a high-end steakhouse (referred to generically as “The Restaurant”) in Dallas’s trendy Uptown district, and Marie hustles a job from him; soon enough he hustles her, pimping her out at a nightclub. The job also requires her to get “order-taking down to a call-and-response that reads each guest’s mind and draws out his selections for three courses with all the pertinent temperatures and modifications in forty-five seconds or less, without letting him feel the slightest bit rushed.” Working at a place where tips occasionally run into four figures, Marie can finally afford health insurance (her story unfolds in the pre-Obamacare early 2000’s), a car, a cozy apartment that doesn’t have black mold on the walls, and after-school care for her daughter. Still, like so many in a precarious economy, she laments that “you never lose the feeling that it’s fragile, your connection to the money.”

Marie’s sex life is likewise just one misstep away from life-altering catastrophe. She was raised with devout, prefeminist sexual attitudes; when a lesbian co-worker strips for her, Marie observes, “I had never seen another woman’s breasts before. I came from such modest people.” Yet Marie soon plunges into postfeminist promiscuity with a mathematical obsessiveness: “In about three months’ time I had sex with approximately thirty different men who worked for or patronized my steakhouse. . . . Three managers, one owner, two sous-chefs, one busser, one bartender, a dozen servers and as many customers. . . . They began to say about me She don’t play and She’s for real.” But as much as Marie tries to convince herself she’s challenging rampant workplace sexism with her own sexual aggression, she knows there’s more to it. “It wasn’t about pleasure,” she confesses. “It was about how some kinds of pain make fine antidotes to others.”

Marie’s deeply conflicted, Bible Belt libertinism isn’t exactly an anomaly in Dallas, a city where old-time religion and unrepentant materialism have cohabited for so long that they’ve spawned all sorts of freaky progeny. But most readers outside Texas (and more than a few within our borders), fed a steady diet of concealed-carry, cowboy-booted caricatures, won’t understand how accurately Tierce skewers the culture of the sprawling, cosmopolitan metro areas where most Texans now live and work. Growing up in the Dallas burbs, Marie is so urbanized that she’d never seen the Milky Way until her fateful church junket to Mexico. The tony microculture she migrates to in Dallas has for decades been emblematic of a city where stylish dining is as integral to civic ritual and self-identity as it is in New York and Paris. Dallas’s top restaurants are theaters where success is conspicuously displayed and the distinctively Texan drama of reinvention plays out night after night. When the performance is over, Marie stays late to polish the tables: “I loved the strangeness of the place when it was empty,” she explains. “That every night we could walk onto a blank stage and invent all that. Take The Restaurant from pristine and silent down to a staggering state of chaotic, deafening, and excessive disarray, and then put it all back together like no one was ever there.”

The cast that struts on this stage is a racial and ethnic mix far more representative of today’s Dallas than the old Southern and Western stereotypes. Marie settles in for a while with a Ghanaian British lover who “plays jazz trombone for a twelve-piece that’s going places and he’s proud of the strong embouchure and extra-muscular tongue he brings me.” The ubiquitous undocumented bussers and dishwashers sympathetically ask, “¿Por qué estás triste, Mari?” The Restaurant is populated with surgeons, lawyers, world travelers, and occasionally the Bishop, a famous African American minister who’s always preceded by his personal photographer. Danny, the indelibly limned, coke- and sex-addicted Bronx Italian restaurant manager, rails at a liquor rep who identifies herself as German and American: “American! There’s no American! What do you mean American?” The only cowboy in sight is Hank Earl Jackson, “a gigantic six-foot-seven alcoholic with a head the size of a steer’s who owned an eponymous bar in the Fort Worth stockyards.” When Hank Earl visits The Restaurant from his swanky hotel residence directly across the street, he’s driven from porte cochere to porte cochere in a town car.

Amid the provocative questions about love, work, and the American dream, Love Me Back also asks (to paraphrase Danny): What do you mean Texan? And that’s why this first novel could well emerge as a milestone in Texas literature. Throughout the twentieth century, most serious Texas writers submitted entirely to a nineteenth-century frontier mythology. And the few who struggled to realistically portray a state radically transformed by a booming economy and mass migration (both across borders and from small towns to big cities) still ended up filtering their visions through that pervasive and increasingly hackneyed myth. Tierce’s Marie, though she reflects on many things, gives almost no thought to being a Texan, much less ruminating on any roots she might have in a long-vanished, overgrazed landscape. Instead, from her turn-of-the-millennium vantage, Marie is the gimlet-eyed prophet of a present in which an ever more diverse population has streamed into our mushrooming metropolitan areas, where many of these arrivals will find no way out of low-wage service industry jobs and little sympathy for the working poor. In refusing to make Marie self-consciously or even identifiably Texan, Tierce allows her to inhabit an authentic, culturally intricate American urbanscape, a setting much more faithful to today’s Texas than the sepia-toned small towns that still persist on the page and screen. Welcome to the twenty-first century, Texas fiction. Your server’s name is Marie, and she’ll take care of you.

- More About:

- Books