This article appeared in the October 2017 issue of Texas Monthly with the headline “Richard Turner’s Full House.”

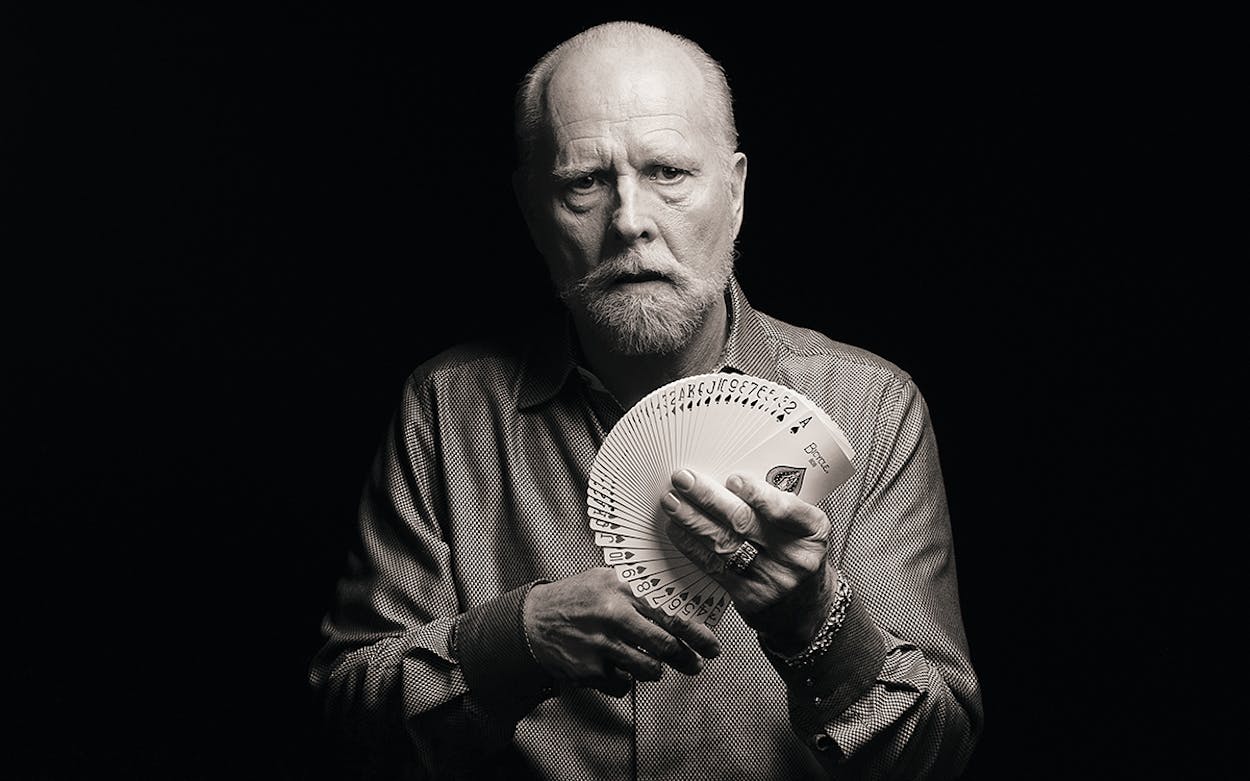

One of the world’s greatest card sharks, true to the old legend about sharks, never stops moving. Seated at a plush green-velvet half-moon card table on the second floor of his San Antonio home, Richard Turner keeps a deck twisting and shuffling in his hands as he describes his decades working to become perhaps the most respected living “card mechanic”—that is, someone who can cheat a card game with sleight of hand. For most of his life, he has practiced an average of fourteen hours a day to master the art of rigging games. He has a closet stuffed with six thousand decks, fresh in their cellophane wrappers. He has a deck on his nightstand, and a waterproof one for the shower. At church, he practices with a special deck, blank on both sides, so that his fellow congregants don’t get a whiff of gambling culture. By Turner’s own estimate, he goes through three to six decks a day—more than 80,000 cards a year.

When he’s not at the card table, the 63-year-old is in his home gym, honing the skills that made him a sixth-degree black belt in karate. That explains his immense biceps, wrapped in tight, short sleeves. Nothing hiding under those.

“I call myself the poster boy for obsessive-compulsive behavior,” he says, as he carefully cuts and shuffles with one hand.

Turner can deal out any game—blackjack, hold ’em, seven-card stud—with any number of players and manage, somehow, to always deal you the winning hand, even if someone else shuffles. And he does it while almost never looking down at the table. There’s no point in his doing so, because he’s completely blind.

For years, as his sight disappeared—he began losing his vision at age nine—he refused to let on that his vision was impaired. Even today, he says, he brings it up only when he thinks it’s relevant. “I’ll be up front and talk about whatever people want to talk about. But for years before that, if someone mentioned it, I’d say ‘What’s that have to do with anything?’ It’s irrelevant. I’d say, ‘You had a colonoscopy, is that right? Did you tell me that?’ ”

That sort of verbal aggression is a close cousin of the competitiveness that drives him, as evidenced by the plaques and photos of sparring matches that adorn the walls of his office. As a young man, he was a daredevil and worked as a stunt coordinator, notably on the seventies-era Wonder Woman series, despite having only fuzzy peripheral vision. He’s made a habit of doing exactly what you tell him he can’t.

“Your sight is your disability,” he says from behind a wide grin. Most mechanics do things based on sight, ensuring they’re moving the right number of cards to a specific spot in the deck, for example. “I do all that by feel. I have an advantage over them in that way.”

At age 21, in possession of a new suit he won on a bet with a salesman, Turner sought out Dai Vernon, then the world’s top card manipulator at the Magic Castle, the magician’s clubhouse/venue in L.A. There he gained a mentor in Vernon and a nemesis in Tony Giorgio, a card manipulator who is best known for playing Bruno Tattaglia in The Godfather. For decades, Turner and Giorgio battled each other, going move for move until someone failed or was stumped.

“We ended up becoming very good friends when I finally earned his respect,” Turner says. In 2007, at age 84, Giorgio called Turner’s skill “incomparable.” When Giorgio died, in 2012, Turner wrote an appreciation of the man he had had such a fraught connection to. “We had a forty-year relationship, a forty-year battle.”

The outlandish story of Turner’s career and life—from performing on riverboats wearing a bowler hat to achieving global acclaim—is the subject of a documentary, Dealt, out this month from a team of producers that includes Houston native Bradley Jackson and Dallas-born director Luke Korem, both of whom worked out of Austin while putting the film together. Watching Turner perform up close, in slow motion and high definition, is worth the viewing. But the arc of Turner’s life, the story of the kid from California who wanted to become a gambler after watching Maverick on TV, and who became an internationally recognized performer, is even more impressive. A preview of the film took an audience award at the South by Southwest Film Festival in March.

And still, despite the professional renown, his mildly advanced age, and his status as a husband and father (he has a son, named Asa Spades Turner), he refuses to play it safe. Because of the injuries he’s sustained practicing karate, he’s had seven hand surgeries—the most recent of which was performed without anesthesia, while he practiced cards with his free hand. (“I wanted to feel everything, to see what it felt like,” he explains.) It’s probably foolish for him to continue practicing martial arts —his livelihood depends on his hands staying injury-free—but Turner seems constitutionally unable to stop challenging himself. “I’m just kind of stubborn,” he says. “I always want to take things to the extreme.”

Unlike many people who have pushed themselves to the outer limits of human possibility, Turner has lived to tell the tale. He didn’t merely win with the hand he was dealt; he’s constantly stacking the deck.