The origins of the names of most large Texas cities are well-known to historians, but there is one huge exception: nobody can say with any certainty how Dallas got its name. Who was the big cheese behind the naming of the Big D?

No one knows for sure, not even the Texas State Historical Association or the City of Dallas’s official website. Decades after the city’s founding, John Neely Bryan, the city’s first white settler, would only say that it was named after “my friend Dallas.” But Bryan, who was suffering from dementia, didn’t furnish a first name.

Who was that friend Dallas? Some look to three men whom Bryan might have known: San Jacinto veteran Walter R. Dallas, whose family owned land near Bryan’s spread; Walter’s brother James L. Dallas, whose only distinction seems to have been that he was briefly a Texas Ranger; and Joseph Dallas, who hailed from a region of Arkansas close to Bryan’s pre-Texas home and later lived in the village of Cedar Springs, which became annexed by the city of Dallas and reborn as the Oak Lawn neighborhood.

We have no evidence to confirm that Bryan knew Walter or James, and while it seems likely that Bryan would have known Joseph, there is nothing in the records to suggest that he was a close friend. None were particularly notable in their time, either nationally or in Texas. (And it isn’t set in stone that Bryan even named the city he settled—as we shall see, one persistent legend has it that the town was named via a contest, open to all residents, that Bryan hosted, while another holds that the town was named by investors many hundreds of miles away.)

The obscurity of Walter, James L., and Joseph Dallas comes in contrast to another set of Dallas brothers — a trio of Pennsylvanians — who were quite well known nationwide in two cases and regionally in the third. It is the best guess of most historians that the name traces back to one of these Dallases.

If you chase this angle far back enough, it begins in Scotland, where the name Dallas originates, and winds its way through Jamaica, where Alexander James Dallas Senior, the father of the three men most likely to have been the source for the city’s name was born, and then Philadelphia, where he rose to prominence.

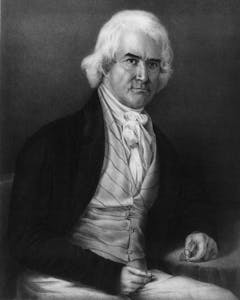

Like another West Indian white man of Scottish parentage named Alexander, Dallas served as Secretary of the Treasury (albeit in the administration of President James Madison and not George Washington). But nobody has ever, or likely will ever, stage a hip-hop Broadway musical about Dallas, who died long before the city or even village of Dallas came to be. It seems unlikely that the city would be named after him, since his sons — contemporaries of the Dallas brothers — were better-known to the founders. Let’s look to them: George Mifflin Dallas, James K. Polk’s veep; Alexander James Dallas, a commodore in the United State Navy; and Trevanion Barlow Dallas, a relatively obscure Pittsburgh judge.

To figure out the true namesake, prepare to embark on a tale of blackface minstrelsy and swashbuckling high seas adventures, a whodunit with the last page maddeningly ripped out.

The Case for Judge Trevanion Barlow Dallas

In 1841 the Republic of Texas granted an Anglo-American syndicate of investors the right to settle much of Northeast Texas. The group was led by William Smalling Peters and his son, another William, and was at least in part bankrolled by their successful endeavors in blackface minstrelsy, arguably America’s first native-born pop music. The younger William Peters, a musician, instrument retailer, and music teacher (like his father before him), was the first to publish the sheet music to the 1831 smash hit “Jump Jim Crow,” the song that both introduced the song title’s term to the American lexicon and conferred on its performer —Thomas “Daddy” Rice—the dubious honor of becoming “the father of American minstrelsy,” the rock and roll of its day. In any event, the land on which Dallas and Fort Worth were built was secured via funds stemming partially from the sales of sheet music about Jim Crow.

When, ten years later, John Neely Bryan built his little cabin on the Trinity late in 1841, he was squatting on land controlled by the Peters family, leading some to believe that he had no right to name any part of it.

Circa 1841, the Peters family were among the leading citizens of Pittsburgh, then a boomtown of 30,000 people. By that time, Trevanion Dallas had migrated west from Philadelphia and was a prominent judge in the town, and like the members of the Peters family, an ardent Jacksonian Democrat.

The families were also clearly connected through the relatives of Stephen Foster Collins, the great American pop composer. Texas A&M at Commerce historian Harry E. Wade speculates that the Collinses, Peterses, and Dallases were all friends, since they shared the same politics and love of music, and lived near each other in a small city in what was then the wild west of America. Collins’s older sisters even took music lessons from the Peters family.

Judge Trevanion Dallas, patriarch of the Pittsburgh Dallas family, died shortly after the contract for the Peters Colony came through, and Wade believes the principals of that colony in Pittsburgh sent word down to the Trinity that they wanted that important settlement named after their friend, Judge Trevanion Dallas.

Wade points out that in accounts from early settlers, the town of Dallas was already a destination they knew about and specifically headed for, which led him to believe that the name originated in the east, not in Texas. He thought that the Peters syndicate was advertising Dallas in eastern newspapers as early as 1842, and cites the memoir of Dallas pioneer John B. Billingsley:

We had heard a great deal about the Trinity and the town of Dallas. This was the center of attraction. It sounded big in the far-off state. We heard of it often, yes, the place, but the town where was it? Two small log cabins, the logs just as nature found them, the walls just high enough for the door boards and the covering of clapboards held to their place with poles, chimneys made of sticks and mud and old mother earth serving as floors; a shelter made of four sticks for a smith shop, a garden fenced in with brush, and mortar in which they beat their corn into meal. This was the town of Dallas and two families; ten or twelve souls were its population.

To Wade, that points to Trevanion, a close friend of the deed holders and prominent Pittsburgher. “What would be more natural than for the Peters family to select the most important settlement in their colony to name after their friend, Trevanion B. Dallas?” Wade asks. “This would account for the widespread use of the name in 1842 and 1843 and also explain why confusion would soon arise. Trevanion B. Dallas was not known outside of Pittsburgh and people would naturally assume that George M. Dallas was the man behind the name.”

Which brings us to the other non-George Dallas brother: Commodore Alexander Dallas.

The Case for the Commodore

The June 20, 1874 edition of the Dallas Weekly Herald claimed that the city was unequivocally named after Commodore Alexander Dallas. That claim has merit: Alexander Dallas had been a minor celebrity for decades by the time the settlement got its name. Military men, especially high-ranking ones, were the rock stars of that belligerent era, and Alexander’s name had been ringing out for about thirty years by the time Bryan arrived at the forks of the Trinity.

Dallas had a storied career in the military. As a twenty-year-old junior officer aboard the USS President, Alexander is sometimes credited with firing the first shot of the War of 1812, even if that cannon blast came in 1811, before the war had commenced. His career was only beginning: he went on to serve with distinction aboard the President and other ships all through the War of 1812, and that was merely the first chapter of his life at sea.

He fought pirates in the Mediterranean. Promoted to commodore, meaning he commanded more than one ship at a time, he took charge of the West Indies Squadron and battled pirates and slave smugglers from the deck of the aging but famous USS Constellation, one of the prides of the American fleet. In 1832, he established Pensacola, Florida’s navy yard, and was also engaged in supporting and transporting infantry up and down the coast in the never-ending Seminole Wars. Fought guerilla-style in swamps and jungles against terrifically tough and motivated Seminoles, those campaigns have been likened by some historians to a nineteenth century version of the Vietnam War.

The Commodore even found himself caught up in the tail end of the Texas Revolution. On April 8, 1836, Invincible, a schooner of the revolutionary Texas Navy, intercepted the Pocket, an American merchant ship. En route to Matamoros out of New Orleans, the Pocket was loaded to the gills with weapons and provisions for Santa Anna’s army. The Invincible forced its surrender and diverted it to Galveston, where the provisions and weaponry were dispatched to Sam Houston’s army just in time for the Battle of San Jacinto, thirteen days after the ship’s capture.

Though Andrew Jackson’s government was extremely sympathetic to the Texan cause, he was ever careful to keep up the appearance of neutrality, and by law, this could be seen as nothing other than an act of piracy. So it was ordered that Commodore Dallas dispatch a sloop-of-war from Pensacola, and in May, the Invincible was taken along with the captain and 46 of her crew, all of whom were jailed in New Orleans on charges of piracy, with the gallows their possible fate. (In the end, the Texas buccaneers walked, but the newly-minted and cash-strapped Texas government had to pay a substantial fine to the U.S. in the aftermath of this incident.)

At almost the exact same time, thanks to Mexican suspicions over Jackson’s tactics toward annexing Texas, tensions between the American and Mexican governments were at an all-time high, even if the two nations were officially at peace. In Tampico, a Gulf Coast port city south of the border, expat Americans complained that they were suffering unspecified indignities at the hands of the locals in the aftermath of Santa Anna’s capture. When word of this reached Jackson, he erupted and dispatched Dallas to the city to enforce gunboat diplomacy on the Mexican port. Dallas’s threat to level the city and kill all its inhabitants— Jackson’s orders— defused the situation with nary a shot fired, and no doubt brought the Commodore a measure of notoriety in Texas.

One more vote for the Commodore: there is a possibly apocryphal but persistent legend that Bryan threw the naming of the town open to a contest open to all 25 or so residents of the then-encampment, and the winning entry was submitted by Charity Morris Gilbert, the first white woman to live in what came to be Dallas. According to this version of events, she submitted Dallas in honor of the Commodore, the liberator of the harried Americans of Tampico.

The Case for George Mifflin Dallas

With both James and Trevanion having such strong arguments, it seems that George, the undisputed namesake of Dallas County, and the man most-cited by lay folks as the namesake for the city, has the weakest case of all. After all, it is firmly established that people called the place Dallas years before he ascended to the number two slot on the Polk ticket, so why would anyone in Texas honor him with a town?

But is his case really that feeble? In the 1840s, George was not the obscure Philadelphia lawyer we are now led to believe. By the time the city of Dallas came into being, he had been mayor of Philadelphia, United States Attorney for the Eastern District of Pennsylvania, U.S. Senator, Pennsylvania state attorney general, and holder of the illustrious-sounding post of Envoy Extraordinary and Minister Plenipotentiary to Russia.

Maps of the United States are littered with towns and counties named after statesmen who accomplished less than Dallas did even before he became Polk’s veep—if you know about the life of the man from whom Denver takes its name, you must either be either from Colorado or a devotee of Kansas territorial politics circa 1855.

All of which brings us full circle. It’s a wild story, from Bryan’s enigmatic “my old friend Dallas” remark down to the feats of the Dallas brothers, on land and sea, in Pittsburgh, Washington, and on the high seas.

Weighing the evidence, it seems George Dallas has the weakest case, even if he is the man now widely assumed to be the town’s namesake. Judge Trevanion is an intriguing dark horse, and his name should still be mentioned in all the speculation about the naming of the town.

But my money’s on the Commodore. Dallas—one of America’s most landlocked towns, where even the city’s river was sluiced away from its downtown—was most likely named after a man renowned for his career at sea.