A blanket of constellations shines brightly over Larry Joe Taylor’s Melody Mountain Ranch in Stephenville, Texas. Out in the darkness, a red beacon flashes behind the colossal stage, illuminating a metal bust of the late, great Rusty Wier with “Make ’em dance, make ’em smile” hanging overhead. In April, the vacant field out front will be jam-packed for his 31st-annual Texas Music Festival, but right now, there’s an eerie stillness as the stage creaks and moans in the wind.

The silence is broken by a song played for the very first time in the distance. It’s coming from inside T-Birds, a private bar on Melody Mountain, which is being used by some of Lubbock’s finest songwriters of the past twenty years. Rising country crooner Randall King belts out the chorus line—”on the corner of Decatur in New Orleans”—from a freshly recorded demo of a newly written song, some five minutes old, called “Calling Home.” Co-writers Ross Cooper and Charlie Shafter join in on a few scattered lines. There’s a glow to their faces as they talk through satisfied smiles and partake in a round of celebratory shots.

The trio is a part of the new Lubbock sound, a collection of singer-songwriters who have called Lubbock home sometime in the past decade, on an annual two-day songwriting retreat.

In the summer of 2016, William Clark Green, the leader of a rocking country Texas act, called me with an idea: a songwriting retreat of solely Lubbock artists. I sent him a list, and a few weeks later, we set a date for the first-ever 806 Songwriter Retreat.

That first group—Green, King, Shafter, Josh Abbott, Brandon Adams, Charlie Stout, Benton Leachman, Dalton Domino, and Cleto Cordero of Flatland Cavalry—had all been christened as rising talent, often making their names at Lubbock’s crowning venue, The Blue Light Live. They came to the weekend to write songs and to get to know one another a little better. Over the next three years, the annual retreats have hosted dozens of up-and-coming Lubbock artists, produced a multitude of songs, and strengthened a scene that’s steadily gaining a reputation as a hotbed for singer-songwriters.

This new wave in the Lubbock sound establishes the artists’ own legacies, while hearkening back to the city’s music mafia of yore: Terry Allen, Jo Harvey Allen, Joe Ely, Butch Hancock, Jimmie Dale Gilmore, Tommy X Hancock, The Maines Brothers.

The twelve songwriters at the 2019 retreat come from a range of backgrounds and sounds, but they’ve all paid their dues in Lubbock’s circuit of dive bars, frat parties, and songwriter circles. There’s Green, the raspy-voiced de facto leader of the group, who’s finally seeing wide-scale success on a national level; Ross Cooper, a former bare-bronc rodeo cowboy, who’s steadily making a name for himself in Nashville; and newcomer Danny Cadra, a veteran songwriter with a country twang and seventies barroom perspective. There’s the cool and quiet Cleto Cordero, whose band, Flatland Cavalry, is skyrocketing towards stardom; Wade Parks, a Spanish teacher who first made a name for himself in Lubbock song circles during the nineties; and Charlie Stout, a wry, denim-jacket-clad photographer originally from West Virginia. There’s Randall King, a smooth country crooner with a honky-tonk streak; Grant Gilbert, a fresh-faced and wide-eyed dreamer looking to score big on the circuit; and Charlie Shafter, a sharp, clever troubadour with wit and a wisdom well beyond his years. There’s Daniel Markham, an effortlessly cool rocker and walking encyclopedia of liner notes; fellow newcomer Stephen St. Clair, another veteran songwriter with a knack for memorable melodies and sharp hooks; and Brandon Adams, who may as well be the godfather of Lubbock’s latest wave of alternative country writers.

As with previous retreats, the first night isn’t focused on writing new songs. Rather, it centers on a crawfish boil, road stories, cover songs, and polishing off a bottle of fine Colonel E.H. Taylor Kentucky Bourbon Whiskey.

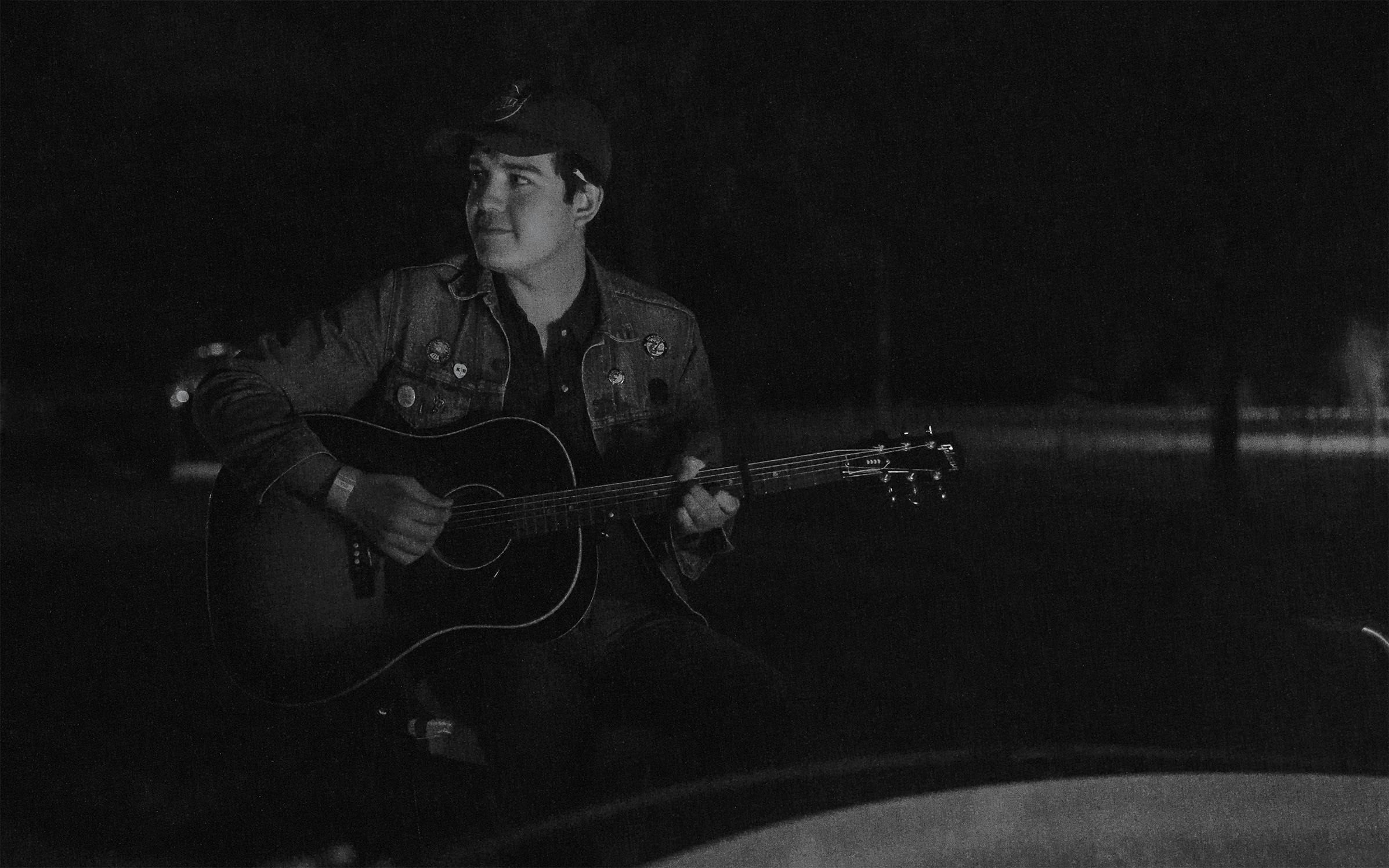

They soon gather around a giant fire pit and start playing songs. Cooper, St. Clair, Cordero, and King play a handful of new ones they’ve recently finished. They’re not just looking to impress, though there are plenty of reassuring head nods from the crowd of their peers. King plays a lullaby ballad about fatherhood, which will undoubtedly be a highlight on his next album.

“This is a little something I was working on the other day. I don’t know where it goes from here, but here’s the first part,” says Cordero. He plays a few fragments of a cowpoke ditty and an “I love you” serenade.

Cooper plays a song called “Brazos,” which he wrote when his nephew was born. It was meant as a gift of sorts, but the song has taken a life of its own and really grown on him.

St. Clair goes into a new one called “Dry Wind.” It silences them. Next time the guitar circles back to him, they ask him to play it again. He does, and follows it up with a St. Clair classic, the chilling “Bismarck.”

The songwriters go a few more rounds until the cold drives them away. The fire dies down and the whiskey wears off.

That next afternoon, after morning coffee brewed by Parks and chicken fajitas grilled for lunch, they throw twelve scraps of paper into a hat and draw partners for fresh writing arrangements.

One pair, Adams and Markham, head off to a little acoustic side stage. Adams tells a story about a guy disappearing on a rural county road in the middle of the night after a heated exchange with his wife. They’ll use it as a launching point for a song called “Ain’t Nobody Out Here Lookin’.”

“Let’s play it from the top and see what rolls out,” says Adams. They have a verse and the outlines of a chorus. It includes a couple of references to legendary Texas metal band Pantera that make both chuckle each time they sing it. Neither writes anything down despite the stack of yellow legal pads Adams bought the day before. They play it from the top and venture into the unknown.

“Meow, meow, meow,” sings Markham when they reach the edge. The filler carries the tune until something sparks. A half-hour later, they have it. They’ll play it a handful more times before Markham pulls his iPhone out and records a quick demo.

Meanwhile, Green walks around barefoot on a shaded patio. He takes a seat across from Cadra, who’s leaning on a bar top with a Bic pen in his hand. They’re working on a phrase Green’s been thinking about for a few weeks, for a song about becoming a better person after a failed relationship.

“How do we make the listener think we’re using this line in this way, before revealing we’re actually turning it around and using it this way?” asks Green. That’s songwriting in a nutshell. They discuss several ways the phrase in question can be used.

“I can smell what you’re stepping in,” Cadra says to Green. They both know where the song must go, but they’re not entirely sure on how to get there. Cadra walks away for a moment, pacing in the early afternoon sun. Sometimes, even in the midst of a co-write, songwriters need their space to think alone.

Green grabs the guitar and tries out lines and phrases as if they’re different pairs of boots. He winces at some, shakes his head at others, gives a “perhaps” nod here and there. There isn’t a roadmap to a successfully written song.

Sometimes, the songwriters use a stopgap line just to get to the next. They’ll end up replacing the filler a couple of times before they’re finished with the tune, which is right in line with some of Green’s most popular breakup anthems. He and Cadra harmonize and sing it all the way through together with a ferocity. It’s bold, booming, and cuts down deep.

“Something’s bothering me, but I just don’t know what it is yet. Let me hear it another 500 times,” says Green after they record a phone demo of the newly penned song, “Best of Me.”

Cooper and Stout seem like natural fits as songwriting partners. They both possess a quick-witted sense of humor and love when they’re able to bury lyrical nuggets, rewarding only the most thorough listeners.

The pair disappears near the large stage for a couple of hours, but come back and set up shop in the main room connected to T-Birds. With a first song, tentatively titled “Long Way Home,” still unfinished, they switch to finish one they started a while back via text message called “Jackalope.”

Cooper had sent over the first few lines of the song, a fun Roger Miller-style picker. It’s right up Stout’s alley and they decide to finish it. It’s prickly, fast-paced, and chock-full of wry grins about the cunning and mischievous fictitious creature of the pasture. They play it a few times, and with each one, you hear them winking at you when a line comes in especially hot.

“It probably needs a little polish, but I think it’s almost certain finished,” says Cooper. They switch out lines in a few verses to make the storytelling more linear, sort out their pronouns and tenses, and hit record.

Later that afternoon, the pairs play their songs on the loudspeakers for everyone to hear. They throw some steaks on the grill for dinner and their names back in the hat for another round of co-writing partners: this time, in groups of three.

In every co-writing session, the groups get at the heart of songwriting. The creative collaboration is a challenging endeavor, requiring you to expose yourself in front of others, knowing there’s a good chance you’re going to stay something stupid before getting on to something worth saying. No one bats a thousand.

There are just as many lows as there are highs, if not more. Profound lines are followed by hollow ideas and unsure stumbles. But the best writes offer something similar to a runner’s high. You think what you just wrote may be one of the best songs written of all time, even if just for the briefest of moments.

The sun is setting and a retreat tradition is underway: Green is peeling onions to make some late-night chili. He always does. Last year, he and Stout wrote a song all about it. Aptly named “The Chili Song,” it’s a charming, Guy Clark-ish earworm that sets the record straight on how proper Texas chili is made: without beans, of course.

At a nearby table, Cordero and Cadra sit across from one another. Cordero has his guitar and notebook in his lap. He repeats lines as Green and Cadra come up with ideas. Nothing sticks. They’ll move on with just a few song sketches to take home.

“I don’t think this is a song I’d listen to,” says Stout.

“Yeah, me either,” says St. Clair.

They’re sitting at a round table with Gilbert, trying to write a song about leaving town after a break-up. It isn’t going anywhere, so the trio abandons it and shifts towards something else. Gilbert mentions he’s always wanted to write a song about El Caminos. It piques the interest of Stout and St. Clair.

“It feels like all your writes are about crazy shit,” says Gilbert to Stout. “El Caminos and jackalopes, that chili song you and Will wrote last year…”

“I’m not sure chili is exactly crazy, Grant, but I get what you’re saying. I take it as a compliment,” says Stout with a laugh as he packs up his guitar.

Their El Camino ode is finished, so they head over to the bar for a round of beer and to check up on everyone else. For the last thirty minutes, they’ve heard King singing “Coming Home” on repeat over the loudspeakers, echoing through the walls and interrupting their focus a time or two.

Cooper, King, and Shafter had to really work for this one, reading through essentially every entry in their song notebooks before the idea takes hold. They try a dark and brooding honky-tonker, a rodeo rocker, a lonesome barroom ballad, and a handful of others before honing in on New Orleans.

The song they create is largely inspired by Cooper’s experience playing in New Orleans earlier this spring. He wasn’t thrilled about being there, and the other two share his sentiments.

“It’s like Las Vegas—it’s a Sin City,” says Cooper. “You know it’s going to make you stay out way past when you want to. It has a way of forcing you into doing what it wants with you.”

There’s always an excitement when a song starts taking shape. At some point, it transitions from just being lines that rhyme to an actual song. Someone will say they may end up cutting it for their next album, but no one really knows if it’ll actually see the light of day. It’s the adrenaline talking.

So far, there’s been a solid track record of songs recorded on the 806 songwriting excursions. Josh Abbott cut “I’m Your Only Flaw,” a song that he and Cordero co-wrote that first year. Green has cut “Drunk Again,” by him and Adams; “Poor,” by him, Adams, and Domino; and “The Chili Song” by him and Stout. King has cut perhaps the most successful song on any of these trips: “Mirror, Mirror” by him, Adams, and Domino. Gilbert recently recorded the breakout single “Denying Desires” by him and Abbott. And Cooper has all the intentions of cutting “Headed Up the Hill,” a border ballad penned by him, Parks, and Adams. He’s been playing it with a full band the last few months.

The retreat has also created more writing opportunities throughout the year, largely for Cooper, who has been joined by Green, Abbott, Adams, and King in Nashville. Plenty of Lubbock co-writes happen outside the two-day Stephenville stint.

The next morning, King and Parks head out early. Most of the others wake up mid-morning, wipe the sleep from their eyes, and decide a plate of Mexican food is necessary before breaking camp. Green, Cooper, Markham, and Stout stay behind and write one more song for good measure, called “Cowboy Picture Show.” You smell salted peanuts and cap guns when they play it. Soon after Markham and Cooper leave that evening, a flurry of messages fills the group’s text message group. Before the day is over, there’s already talk of setting dates for an additional retreat in the fall.

“We aren’t here for our egos or to hurt anyone’s feelings,” says Green. “We want others to do this very thing. If you’re from Ft. Worth, Houston, San Marcos—wherever—go start your own retreat. I love Lubbock and what it’s given to me. That’s what this is about. I think it’s been a special place. At the end of the day, this is about writing songs. That’s what we came to do.”