Following the world premiere of the documentary Raise Hell at January’s Sundance Film Festival, producer James Egan instructed the 324 (or so) audience members to stand, raise their right hands, and repeat after him.

“I promise.”

I promise.

“To do whatever I can.”

To do whatever I can.

“To protect freedom of speech.”

To protect freedom of speech.

“And freedom of the press.”

And freedom of the press.

“So help me Molly.”

SO HELP ME MOLLY!

It’s been 12 years since author, political commentator, and humorist Molly Ivins died from cancer at the age of 62, and she’s far from forgotten. She’s been the subject of a 2009 biography by Bill Minutaglio and W. Michael Smith, as well as Margaret and Allison Engel’s 2010 one-woman show Red Hot Patriot: The Kick-Ass Wit of Molly Ivins, which originally starred Kathleen Turner. Each year since 2008, the Texas Observer has given out the Molly National Journalism Prize in honor of its most celebrated contributor. In these Trumpian times, she also lives on whenever someone tweets that a speech or comment was “better in the original German,” plagiarizing (or paying homage to) Ivins’s quip about Pat Buchanan’s speech at the 1992 Republican National Convention.

Now comes Raise Hell: The Life & Times of Molly Ivins, from director Janice Engel (no relation to the playwrights) and producers Egan and Carlisle Vandevoort. Seven years in the making, the documentary will screen at the SXSW Film Festival, first at Austin’s Paramount Theatre on March 11.

Ivins is known to all Texans—and many Americans—of a certain age. They read her in the Observer or the Dallas Times Herald or via national syndication, saw her on C-SPAN or Late Night With David Letterman, and reveled in her salty quips about the Texas legislature. In 1993, when Representatives Warren Chisum and Talmadge Heflin made a then-successful attempt to reintroduce both homosexual and heterosexual sodomy as crimes under the Texas Penal Code, she joked that the Texas House sergeant-at-arms needed to reprimand them for their backslaps and high-fives, as “under the provisions of the amendments just passed, it is now illegal for a prick to touch an asshole in this state.”

Ivins’s work was largely pre-internet boom, and definitely pre-Twitter and Facebook. In that sense, the film is a gift to the online generation, as well anyone outside of Texas who never had the chance to encounter her work. That’s a group that once included Egan and Engel, both of whom came to Ivins via Red Hot Patriot. After Egan first saw the play in L.A. in 2012, he came home raving that there ought to be a film about her. His husband, writer and journalist Dan Perdios, pointed to the shelves above their bed, where there were several of Ivins’s books, including Molly Ivins Can’t Say That, Can She? and Bushwacked!

“I said, ‘Oh my God, this is crazy,’” Egan says. “I’m sleeping under Molly Ivins.” He figured that if he—a California professor, filmmaker, and social activist—didn’t know Ivins’s story, then a lot of people didn’t.

He took his friend Engel, a New Yorker whose previous films include documentaries about the musicians Ted Hawkins and Jackson Browne, to see the show, and she was similarly blown away. “When I went home after the play, I Googled Molly, and I watched several C-SPAN clips, and I was like, ‘Shit!’” Engel says. “‘Oh my God, this woman!’ The wryness—she’s like a bite a minute—but also the depth of who she was.”

A self-described diminutive Jewish New Yorker, Engel nevertheless identified with Ivins, a six-foot-tall, redheaded Texan. Engel was already anti-Nixon at age ten and, like Ivins, had always chafed at patriarchal authority figures, including her own father. Earlier in her career, Engel worked as an editor on the documentary Legend of the Hollywood Blacklist, an experience she carried with her as she continued rising in the business. “I would walk into meetings and [think], ‘Who in this room would name names?’” she says.

Of course, it wouldn’t seem right to have two “coastal elites” as the sole drivers behind a Molly Ivins movie. Completing the filmmaking triumvirate was Vandevoort, a longtime Houston LGBT activist whose background mirrors Ivins: she was raised in River Oaks, attended St. John’s School, and her parents worked in oil. Vandevoort’s role was not merely to act as Texas ombudsperson and bullshit detector, but also as a rainmaker. “There was no way that James or Janice could ask for money from Republicans and Democrats in Texas that profited from the oil and gas business,” she says. “I had the understanding of how to talk to those people.”

They started with $10,000 of their own money on credit cards, did some traditional fundraising, and then launched a Kickstarter in 2015, which collected $120,000 and nurtured a community of Ivins acolytes. The crowdfunding was boosted by four people with large social media followings: writer Anne Lamott and musician Bonnie Raitt (friends of Ivins), Jackson Browne (a friend of both Raitt’s and Engel’s), and actress Morgan Fairchild (“a big policy wonk and a Texan,” Vandevoort says).

The film’s production process ran for so long that producers competed with both Wendy Davis (2014 gubernatorial candidate) and Beto O’Rourke (2018 U.S. Senate candidate) for liberal donors. After last year’s midterms, Katie Drake Bettner of McKinney stepped up with enough money to get Raise Hell finished just in time for Sundance. Bettner also executive produced last year’s election-finance documentary, Dark Money, and has worked on several other films (her husband, Paul, co-created Words With Friends, and the two of them now run the Playful gaming company).

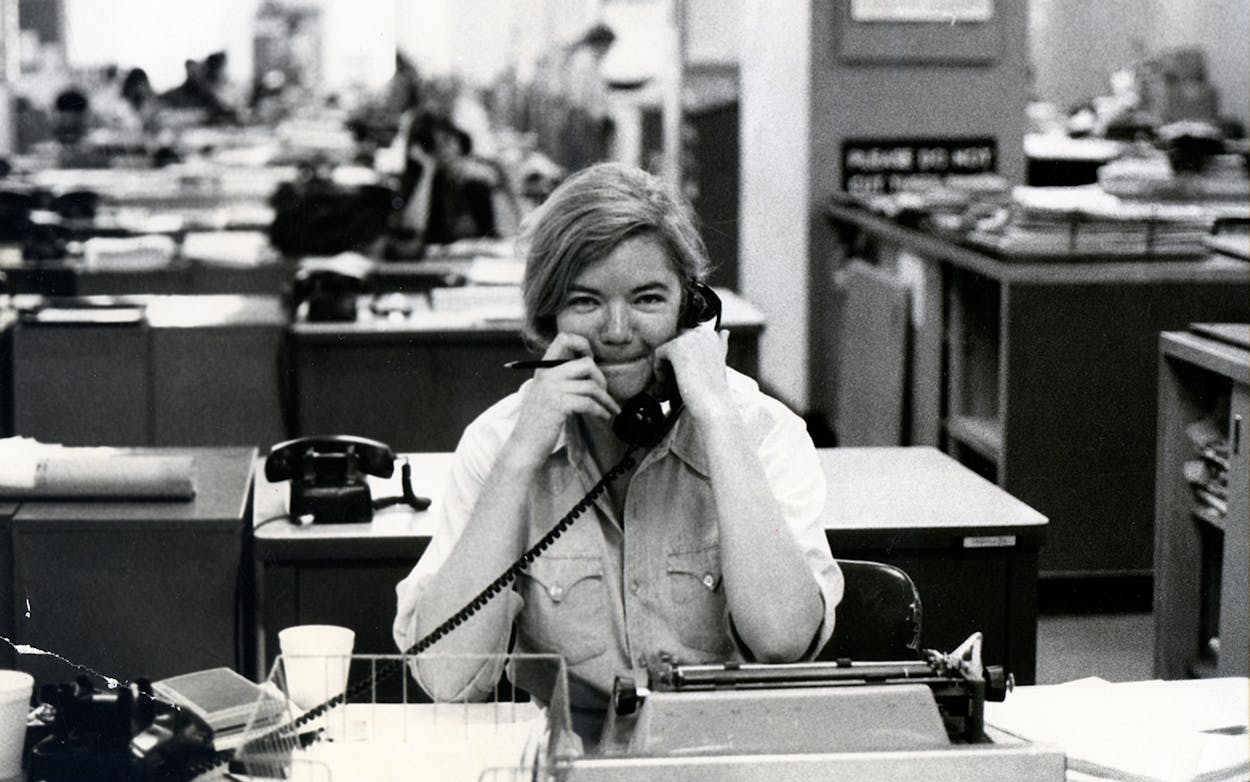

Most striking to Engel, and what comes through repeatedly in the film, is how ahead of her time Ivins was, both as a political mind and a woman working in journalism (sexism recounted in the film is simultaneously shocking and unchanged). In some ways Ivins was the original liberal blogger, a precursor to both MSNBC and politically-minded talk show hosts like Jon Stewart and Stephen Colbert—someone who trafficked in reportage and punditry but also comedy and advocacy. She was talking about “the 1 percent” and opining that the true political spectrum was “top to bottom, not left to right,” decades ago. (So were others, of course, but they weren’t nationally syndicated mainstream newspaper columnists.) She also suffered as many trolls as anyone in the social media age. It’s just that the hateful rants she received arrived via snail mail. “I don’t look at the letters written on Big Chief tablets in red crayon,” she once told Bryant Gumbel.

Ivins famously could drink any politician or lobbyist under the table, which made her very good at cultivating sources but was also a lifelong burden. “The more I got to know her, the more my heart opened to her,” Engel says. “I really saw what she was up against. She had a sense of her own brilliance, but she also knew she was a hardcore alcoholic when she was 29.” (This fact comes from a letter Ivins wrote to herself at that age, which is among her papers at UT-Austin’s Dolph Briscoe Center for American History and is briefly excerpted in Raise Hell. Ivins ultimately got sober in 2005).

Speaking on behalf of all of Ivins’s political targets, former Texas Lieutenant Governor Ben Barnes says in the film that you ultimately couldn’t be mad at her because “Many times you didn’t know what the heck you were talking about, and Molly did.” The movie features extensive interviews with Ivins’s friends and family, including her Observer colleagues Kaye Northcott, Ronnie Dugger, and Lou Dubose; longtime CBS news anchor Dan Rather; and former Planned Parenthood president Cecile Richards. Richards’s mother, former Texas governor Ann Richards, appears in archival footage, but the filmmakers weren’t able to get former president George W. Bush (whom Ivins derisively referred to as “Dubya” or “Shrub”) or former governor Rick Perry.

The film’s dramatic centerpiece, and also something of a scoop, is a previously little-seen (except on YouTube) interview with an apparently hung-over Ivins in Chicago in 1996. Engel and Vandevoort couldn’t believe how wrung-out she’d looked—like she was coming off a bender. Yet it’s the substance of the footage that was so intense. Ivins expresses her disgust for Clinton, whom she’d previously supported, over welfare reform, and proclaims that she doesn’t plan to cast a vote in the 1996 presidential election. “I want something on the ballot that says ‘It makes me vomit,’” Ivins says in the clip.

Since the film’s production began, Engel has found herself talking to Ivins or invoking her during meditation sessions. She also dreams about her. While Engel was staying in Austin in 2015, Ivins appeared to her as she slept. They were together at a fancy penthouse dinner party in Manhattan, and Ivins was outside a sliding glass door. She came up to Engel and said, almost Citizen Kane-like, a single word. A word Engel still can’t remember.

“I actually said in the dream, ‘That’s like fifty-point, triple-bonus Scrabble,” Engel says. “’Like, wow, Molly. That’s a major word!’ And she just gave me this big Molly smile, and I woke up. That smile. My heart just exploded.”

- More About:

- Film & TV

- Documentary

- Molly Ivins

- Austin