When I was a young one, back in the seventies, a good part of my summers, like so many young Texans’ before and since, was spent away at camp. First, I went to stalwart Camp Longhorn, on the banks of Inks Lake, near Burnet, where I took part in all the standard activities, such as swimming, riflery, archery, and short-sheeting. Then, for a few years, I went to rugged Prude Ranch, in the Davis Mountains, which also had riflery, archery, and short-sheeting but, being situated in the high desert as it is, focused less on watery activities and more on horses. I had fun at both places, although my memories are a little foggy.

My wife was also a camper in her Texas youth, spending time on a beautiful stretch of the South Fork of the Guadalupe River, at Camp Arrowhead for Girls, in Hunt. Since the camp’s opening, in 1934, the campers had been split into two tribes, Kickapoos and Pawnees. Kendall’s mom, a Marlin native, had been a Kickapoo at Arrowhead in the fifties, and so Kendall was a Kickapoo there in the seventies and eighties. In a strange coincidence, my own mother, who grew up in Abilene, had gone to Arrowhead in the forties. And she too had been a Kickapoo. If I ever end up on the psychotherapist’s couch, we’ll have plenty to talk about.

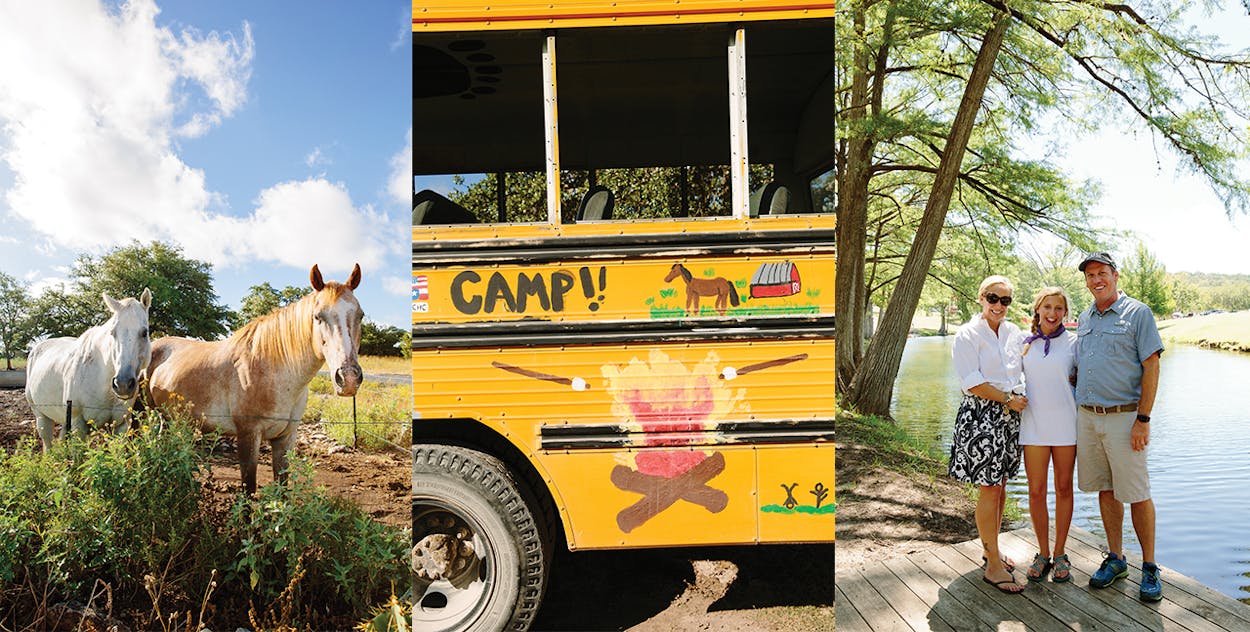

By the time my daughter, Sarah, was of camp age, Arrowhead had unfortunately ceased to exist. Luckily, the camp’s longtime director, Sandra Schmitt, and her core staff, who had all been at Arrowhead when Kendall was a camper, had thrown down new stakes a few miles away on a tributary of the Guadalupe River’s North Fork, opening Camp Honey Creek for Girls with all the old Arrowhead traditions intact in the summer of 2002.

And so it was that at the crack of dawn on a July morning in 2009, Kendall and I loaded up a trunk, two overstuffed duffel bags, and Sarah, who was then six years old, and headed west out of Austin toward Camp Honey Creek. As we waited in a growing line of cars outside the camp’s gate that morning, Kendall got out and chatted with a few of the moms, some of whom she thought she might have recognized from her days at Arrowhead. “Oh, I think I went to camp with her! I don’t remember her name. Is that Louise?! That looks like Dottie! I think Crickett’s supposed to be here. Oh, there’s Schmitty!” After Sarah had been assigned one of the unair-conditioned cabins that would soon be filled with a dozen six- and seven-year-olds, Kendall quickly unpacked the trunk and duffels and made up the bunk. We kissed our little girl, said goodbye, and headed back to Austin hoping for the best.

The plan was for her to stay at least ten days, an abbreviated version of a full four-week term. Or, if she was game, she could stretch it to two weeks. Or she could stay the full month. At a ceremony that night, Sarah became perhaps the only double third-generation Kickapoo ever and, a week later, called to proclaim that she was staying the full term. Like her mom and dad and grandmothers before her, the camping life was in her blood.

All that is required of parents after drop-off at most camps is the expectation that they’ll return to pick up their children at camp closing. Honey Creek is very different in this regard. There is no visiting the weekend immediately following drop-off, but the weekend after that, the tribes put on hilarious skits known as Tribe Shows and we do visit. We don’t visit the next weekend, but then it’s Horse Show and we do visit (Sarah got a third-place ribbon for Western this year!). Then it’s camp closing and we do, of course, go down for that.

So this summer, I did what I’ve done the previous seven: I drove to Hunt and visited camp—a lot. And I’ve come to love the whole rigmarole. A typical itinerary for these annual jaunts has Kendall and her mother and I (sadly, my mother passed away in 2005) taking off Friday afternoon or Saturday morning. Eager to get there, we don’t dally too much along the way, although we do sometimes stop outside Dripping Springs, where there’s a gourmet Neapolitan pizzeria famous for its house-smoked pastrami. Satisfied, it’s on to Johnson City (Who wants to stop by the Real Ale taproom in Blanco?), Fredericksburg (Anyone up for some peach ice cream?), Ingram (Dam-sliding, anyone?), and, right on time, Camp Honey Creek.

When we arrive, the two-hundred-plus six- to seventeen-year-old girls are milling about the grounds. Sarah’s happy to see us (we have a cooler full of her favorites: fudge, Mexican Cokes, and Topo Chico). After seven summers she’s an old hand and responds to the parental inquisition without much thought: she’s doing great, camp is awesome (her horse’s name is Rusty), and everything is just fine.

Since Sarah started going to camp, Kendall has reunited with a whole slew of women she went to camp with a generation ago. They stayed in touch for a short while after their camp days and maybe bumped into one another during college or at a wedding, but in most cases, it had been decades—marriages, children, professional successes, divorces, illnesses, deaths, and other landmarks. In short, life. It has been fascinating to witness, like the opening of a time capsule filled with adolescent acquaintances.

Relationships of this sort require lots of catching up, and what better venue for this than the very river upon which these friendships were originally formed? So, while our girls are at camp with their new friends making their own memories, we parents jump in the Guadalupe and float in the sun-dappled shadows of ancient cypresses, sipping cold beer and chilled wine. The husbands shoot the breeze in one pod, and the former Kickapoos and Pawnees form their own more lively flotilla. Kendall is there with her mom and a sister, who also has a daughter at Honey Creek. Suzanne, Beth, and Cynda are there with their mom, and so are Louise and her mom, and Dottie, and Crickett. I imagine my mom out there too. Hey, how about an old camp song?

If we’re lucky, we’ve got three or four more summers of the same ahead of us. After that, I don’t know what we’ll do. Sarah will probably go off to college, and then she’ll likely start a career. Maybe there’ll be a marriage and maybe there’ll be kids. Perhaps, in thirty years or so, we’ll all be back, visiting camp and floating on the Guadalupe with old friends. I wouldn’t mind that. It’s not a bad way to spend a summer.