Asking professional photographers to take pictures of bluebonnets is like asking a concert pianist to play “Auld Lang Syne.” They can do it, for sure—better than you can, no doubt—but what’s the point? When they look through their viewfinders, the Mary Ellen Marks and Dorothea Langes of the world strive to capture people and places that usually escape our notice, or to make the familiar fresh or unreal. By contrast, the traditional bluebonnet photograph—smiling siblings posed in matching outfits or sitting in their parents’ laps or hugging their beloved Labrador, all amid a field of purplish blue and green—is an object of sentiment, with artistic ambitions that rank one step above those of the crayon-wrought stick-figure drawings on your refrigerator door. Even San Antonio’s native son Julian Onderdonk, who a century ago painted Spring Morning, that iconic study in azure and indigo, was said to have loathed being known as a “bluebonnet painter.”

But even those who regard the traditional bluebonnet photo as hackneyed can’t help but reserve a certain affection for it. (And the same concert pianist who disdains playing “Auld Lang Syne” in front of an audience may get drunk and warble it enthusiastically at the stroke of midnight on New Year’s Eve.) So might it be possible to bridge these two sensibilities, to create bluebonnet photos that strive for artistry and still hew to our love of the state flower? To find out—and to mark the peak of wildflower season—we asked seven photographers to throw off their (and our) preconceptions and make us see this humble flower with new eyes. The results we received ranged from the reverent to the nostalgic to the cheeky to the profane. As even the most austere of these photos make clear, absent cherubic toddlers and poorly chosen shutter speeds, Lupinus texensis remains a beauty to behold.—Jeff Salamon

ADAM VOORHES

My goal was to show the bluebonnet in a way that people don’t usually perceive it, while still being true to the flower. I’m interested in shape and texture and how an object relates to light. The trouble is, the flowers are so damn tiny. An orchid or poppy has huge petals that light can wrap around. Light gradates across a textured surface and accentuates shape; it brings visual interest to a subject. That isn’t the case with the bluebonnet.

RANDAL FORD

I think the traditional bluebonnet photo can be a bit cheesy, but it’s an iconic Texan thing. My folks certainly took those sorts of photos of me when I was growing up in Dallas in the eighties. After I got the assignment to contribute to this package, I was having lunch with a friend, who mentioned that his dog, Oscar, is a Blue Lacy and that the Blue Lacy is the state dog breed of Texas. And I thought, “That’d be perfect, to photograph the state dog of Texas with the state flower!” So I set up a makeshift studio in my friend’s garage in Austin, placed a gray screen behind Oscar, and shot him that way. Then I shot some bluebonnets out on Southwest Parkway, in Austin, and collaged the two shots together using Photoshop. It might have been nice to actually shoot Oscar in a field of bluebonnets, but he is too hyper and has too short an attention span to pull that off. A Blue Lacy isn’t your Uncle Joe’s fat Lab!

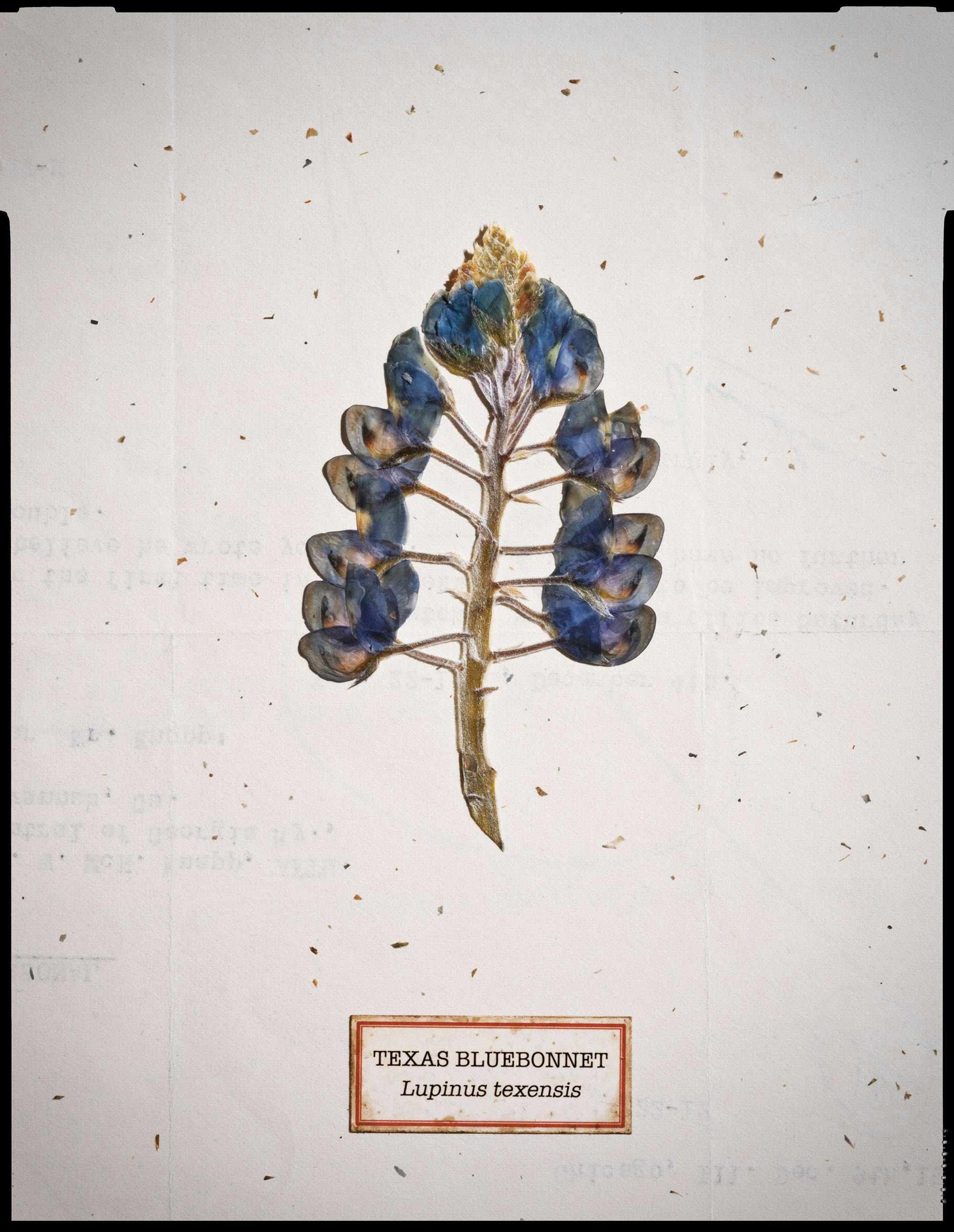

DAN WINTERS

I know that the genre of shooting kids with bluebonnets goes way back, but I was imagining someone picking a bluebonnet and preserving it as part of a botanical specimen collection. The main challenge was to take a bluebonnet that I had picked a few hours earlier from the meadows surrounding my studio in Driftwood and make it look like it was mounted one hundred years ago. I pulled this off by flattening it in a high-temperature dry-mount press, which I think gives it a pretty convincing archival look.

SARAH WILSON

Though I grew up in the eighties, not the sixties, the midcentury parents in the photo more or less represent my parents. It was always a struggle to get my sister and me to smile and pose for bluebonnet photos. Looking at the smiling shots they took of us, you’d never guess that I had spent several hours beforehand screaming and crying because I was forced to wear a dress. My parents must have bribed me with something really special!

LAURENCE PARENT

I’d been running around shooting flowers all day in Llano and Blanco counties in boring overcast light. When it looked like the sun might burn through for a bit, I remembered these railroad tracks nearby that would make for a good shot. So I drove over there, jumped out of my truck just as the sun peeked out, and sprinted down the tracks about a half mile to get the best flowers before the light disappeared. Dramatic sky, bluebonnets—how could I not take a picture?

WILL VAN OVERBEEK

This photo was taken on a ranch near Fredericksburg that some cycling friends told me had particularly beautiful flowers. The lady who lives there took me on a little driving tour of the land. That was when I saw the donkeys, which I decided had to be in the picture. At first I was shocked when the lady drove her four-wheeler over a lush patch of flowers. Only later did I realize that the tire tracks made the perfect shape, leading the eye deeper into the picture.

WYATT McSPADDEN

Twenty years ago, right after I moved to Austin from Amarillo, I patronized a photo lab whose owner was a zany character named Jeff. One day he showed me an eight-by-ten color print of him pushing a lawn mower through a patch of bluebonnets. He thought it was funny, and I thought it was funny too. Being from the Panhandle, I had no sense of the reverence folks down here have for bluebonnets—in Amarillo, we had our pictures taken in piles of dirt. Twenty years later I concocted my own variation. I have a buddy who has a riding mower, some property west of Austin, and an overabundance of bluebonnets, so I just went to work. Just me, a cheap cigar, a Lone Star tallboy, and a riding mower.