In the early days of the FDR administration, Kenneth Threadgill—a yodeler who’d been mentored by Jimmie Rodgers, the father of country music—bought a Gulf gas station on the two-lane highway linking Austin to Waco, on a street that later became known as North Lamar. Threadgill, who’d once been a bootlegger, secured the first post-Prohibition license to sell beer in Travis County and transformed the filling station into a tavern. After World War II, he started hosting live music at the watering hole.

Threadgill’s had become a linchpin for Austin’s budding folk music scene by the early sixties, with the likes of the Hootenanny Hoots and the Waller Creek Boys as regular performers. A couple of members of the Hoots, Julie and Chuck Joyce, introduced UT undergraduate Janis Joplin to the Threadgill’s scene in the early sixties. With Kenneth’s encouragement, she began singing at the crowded beer joint.

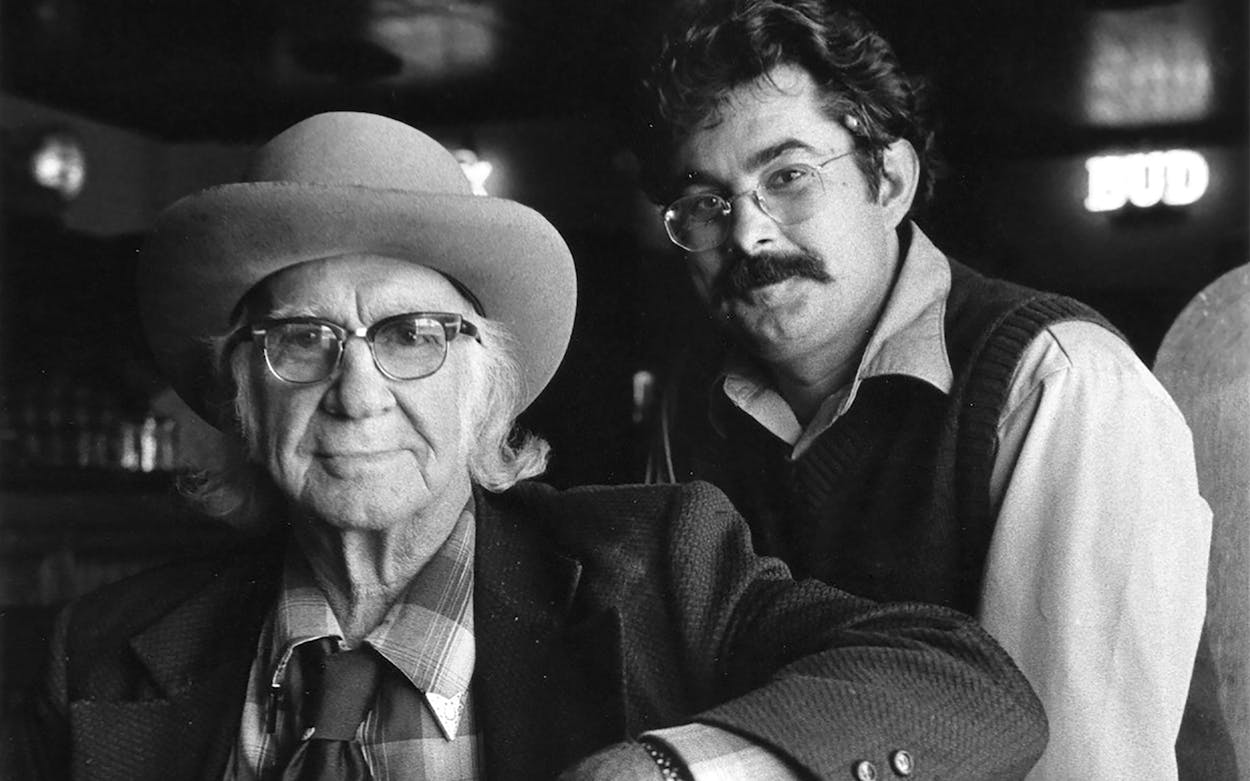

But by the late 1970s, Threadgill’s Tavern had been closed for several years, following a period of disrepair. The building was nearly collapsed when Eddie Wilson bought the property from Threadgill in 1977. Eddie had founded the influential Austin venue Armadillo World Headquarters in 1970, but by the end of the decade, he decided to step away from it. He’d already had success starting one restaurant in town, the legendary Raw Deal, and envisioned Threadgill’s Tavern morphing into an intimate concert venue that could seat around a hundred people. There, he could also serve down-home cooking like his mother, Beulah, made when he was growing up. So Eddie threw himself into giving Threadgill’s a new life.

When the new iteration of the venue emerged in the early 1980s, it became one of the first businesses to promote Austin’s homegrown culture. Eddie had long been an inveterate collector of concert posters, beer signs, and photographs, among other things, most of it related to the vibrant musical scenes percolating in his hometown. Joplin and her mentor Threadgill, who died in 1987, were pictured prominently in between the ephemera hanging from the walls. The place became a showplace of Austin artifacts, and stepping into Threadgill’s was not unlike entering a museum—only one with, say, Carrie Rodriguez fiddling alongside Don Walser while the waitstaff served the best pecan pie around and, on Thursdays, chicken and dumplings to die for.

I ate plenty of stick-to-your-ribs food at Threadgill’s, stretching back to the eighties. Richard Lord’s Boxing Gym, where I train, was located next door to the venue for more than a decade. Sweat-drenched and exhausted, I stopped by Threadgill’s at least once a week to pick up an oyster po’boy with peach cobbler to go. I was part of a group of writer friends, whom Jesse Sublett dubbed “the Knuckleheads,” that began meeting there semi-regularly for lunch. Eddie was our host. Though not a writer, he is one of the all-time great storytellers, so he became a Knucklehead himself, and regaled us with absurd tales over chicken-fried steak and King Ranch casserole.

Sometimes I’d meet Eddie for lunch, and we’d sit together in his more or less private booth near the bar and catch up. We’d always end up talking about the history and culture of Austin, especially the many eccentrics who’ve called this place home, of which Eddie possesses an encyclopedic knowledge. Plenty of aged hippies, with white hair chocked back in ponytails, would be there, sitting by millennials with plenty of tattoos and piercings, as well as blue-collar workers, insurance agents, lawyers, and cops. It wasn’t unusual to see, say, Joe Nick Patoski interviewing legendary singer-songwriter Willis Alan Ramsey over lunch, or the actor Sonny Carl Davis dropping by Eddie’s booth with an update on his latest film project.

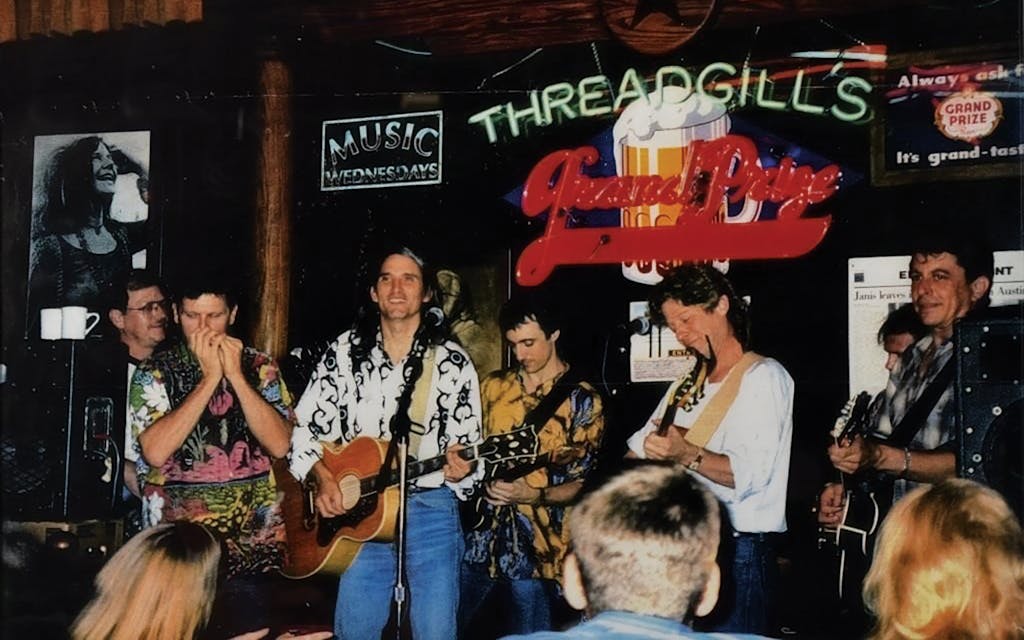

One of the many upgrades Eddie installed was a stage at the north end of the main dining room. (During Janis’s time, performers stood on the linoleum alongside the beer joint patrons.) In the late 1980s and the 1990s, you might catch Jimmie Dale Gilmore, returning to music after years at an ashram in Colorado, performing on a Wednesday with backing from Champ Hood, who died of cancer in 2001. Once Gilmore left after signing a major-label deal, Hood took over with the Threadgill’s Troubadours, owning Wednesdays for a decade. Hood also played there with Uncle Walt’s Band, featuring Americana music pioneer Walter Hyatt and David Ball, who would become a platinum-selling country star.

Rose Flores, Sarah Fox and Joel Guzman (Los Aztex), Butch Hancock, Joe Ely, Joe King Carrasco, and Tish Hinojosa, and many others brought the house down with their songwriting and storytelling, and I distinctly remember the modern-day honky-tonk master James Hand giving a particularly moving reading of his plaintive songs a few years before his death. I was honored to take the stage myself several times, too, to read poetry and sections from my nonfiction books.

But Austin’s skyrocketing property taxes have vexed Eddie and his wife Sandra, who co-owned Threadgill’s for decades; they were a primary reason Old No. 1’s downtown sister store, Threadgill’s World Headquarters, went out of business two years ago (it opened in 1996). It’s a familiar story for mom-and-pop operations around town. For years, Eddie tried to formulate plans to keep Threadgill’s viable.

That includes the nonprofit Museum of Austin Culture, which collects, conserves, and exhibits concert posters and other musical memorabilia. The museum entered into an agreement with Eddie to move into a two-story building on the Threadgill’s property behind the restaurant, and opened toward the end of 2019. But before the art showcase could get comfortable in its new digs, the pandemic struck.

In early March, I met two of my Knucklehead buddies, David Marion Wilkinson and the late Jan Reid, for lunch at Old No. 1. The coronavirus pandemic was unfolding, though restaurant closings had yet to begin, and the mood was eerie. We were practically the only three diners in the place. Two days later, Eddie and Sandra closed Threadgill’s as lockdowns took effect nationally. A month after that, the Wilsons announced that their restaurant wouldn’t reopen. As they put it, it seemed like a good time to retire.

Burley Auction Gallery sold the last batch of the Wilsons’ “relics & memorabilia” from the Old No. 1 store last month, including treasures such as rare Jim Franklin armadillo paintings used in a Lone Star beer ad campaign in the eighties, hundreds of Armadillo World Headquarters concert posters, and books from Eddie’s personal library. The last of a series of memorabilia auctions Burley conducted going back to the closing of the downtown store, the auction attracted bidders from around the world. I participated in an earlier auction, hoping to nab a poster for the first Waylon Jennings concert at the Armadillo in the early seventies. I’d planned to bid as much as $500, which, as it turned out, was laughably low.

The building has to be vacated before December 3, when the new owner, a residential property developer, takes possession of it. Ahead of its closing, Eddie worked out a deal with auctioneer Robb Burley to stage a series of concerts through the fall to commemorate Threadgill’s cultural heritage. Music echoed through the old building for what would be the final time, with performances by the likes of Jack Ingram, Bruce Robison and Kelly Willis, Charley Crockett, Shinyribs’ Kevin Russell and the Shiny Soul Sisters, Dale Watson, and Gary P. Nunn. Then Threadgill’s went silent for good.

- More About:

- Music

- Janis Joplin