During a G-7 summit meeting in 1981, President Ronald Reagan, drew pictures on a scrap of paper: a few heads, including, possibly, his own; an eye; and a muscular torso. The British prime minister Margaret Thatcher snagged the scrap of paper after seeing it abandoned on the desk after the meeting. When the drawings were discovered among her papers years later, one psychology professor tried to interpret Reagan’s thoughts: “The eye means I’m watching what’s going on, I’m observing, but I’m not altogether there.” The doodle was seen as proof that Reagan was bored and not entirely attentive.

But Sunni Brown is one of a number of consultants who have built a career around the opposite conviction: that doodles help us think and perform better. Even when the art is off-topic, Brown believes, the added stimulation can anchor a drawer in the present. Her Austin-based creative consultancy, SB Ink, specializes in “performance infodoodling,” a term she trademarked to describe the practice of illustrating, in real time and in a large format, speeches and other information shared with a group. (In 2009 she infodoodled the keynote speeches at South by Southwest.) She also leads numerous doodling workshops as well as drawing-based problem-solving sessions. Her clients include a major retailer and several large news media companies, like Nike, Turner Broadcasting, Zappos, and Disney.

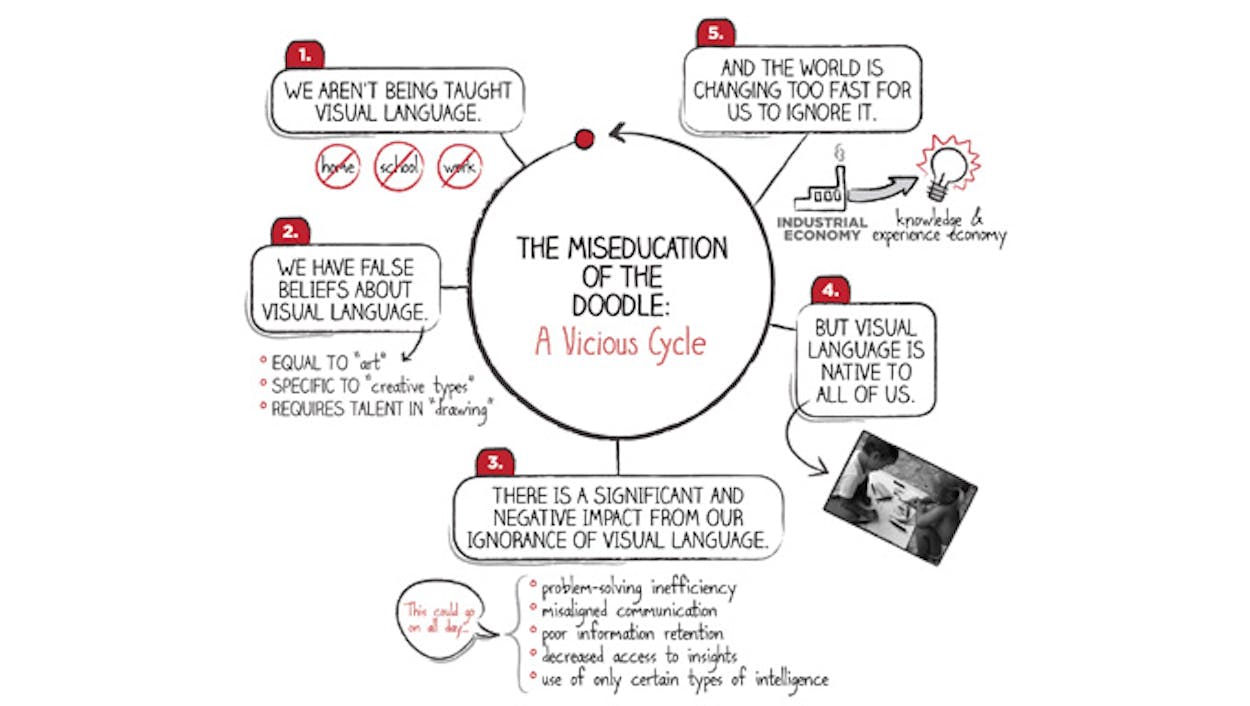

Brown’s book The Doodle Revolution: Unlock the Power to Think Differently will be published by Penguin Portfolio in January. In the book, which is part manifesto, part goofy how-to workbook, Brown discusses the power of doodles, arguing that they result in higher retention. Visual displays, she says, lead to faster decision-making and help clarify problems. The book offers doodling tips, including exercises like to give stick figures expressions using permutations of three different curves for eyebrows and mouths; and broader applications for businesses, like how to take real-time graphic notes and lead group doodling sessions, which, she says, encourage shared memories and creative breakthroughs.

Visual note-taking is sometimes referred to as “graphic recording,” but Brown deliberately uses the word “doodle”—which is self-deprecating and silly—to reach the broadest audience and to disarm readers concerned about their artistic abilities. Even the ugliest visualizations can help clarify complex concepts, she said.

Her book is not the first of its kind. Dan Roam, another visual thinking consultant, published The Back of the Napkin: Solving Problems and Selling Ideas With Pictures in 2008, and it turned out to be a best-seller. “There’s extraordinary applications for visual thinking in science, education, law and medicine,” Roam said, mentioning that litigators have used professional doodlers to clarify arguments for juries. But business is “where ideas get listened to.”

The formal practice of facilitating meetings with drawings began in 1972 with David Sibbet’s workshops at the San Francisco branch of the Coro Foundation, an organization that prepares individuals for ethical leadership in public affairs.

Michael Doyle, an architect who attended Sibbet’s first workshop, was inspired to start Interaction Associates, a consulting firm, with David Straus; the three men shared tips throughout the seventies. In 1979, Sibbet formed his own strategic planning and graphic facilitation company, and in 1980 he published I See What You Mean: A Workbook Guide to Group Graphics, the first book on the subject. His company, now the Grove Consultants International, still operates in San Francisco for clients like Apple Computers, Procter & Gamble, and Visa.

Whereas there were an estimated ten graphic facilitators in the seventies, and perhaps a hundred in the early 2000s, now Sibbet and Brown estimate that there are now thousands worldwide. The mushrooming was “coincidental with the development of the digital camera and color printers and sharing capabilities,” Sibbet said.

Brown first became acquainted with graphic facilitation as Sibbet’s executive assistant in 2005. Brown, a graduate of the Lyndon B. Johnson School of Public Affairs at the University of Texas at Austin, had no artistic background, but she eagerly observed and volunteered.

“Parts of my mind that were not available were available,” Brown said. “I feel like I got smarter really quickly.”

Having grown up an ambitious child in Huntsville, she was very aware, she said, of how “having access to information” affected people’s quality of life.

After learning this new skill, “there was no way for me not to become radicalized,” she said.

In 2007, Brown brought graphic facilitation to Austin, a city known for attracting entrepreneurs and creative-minded people, a constituency she thought would be particularly receptive to visual thinking. She soon began giving presentations and hosting workshops internationally to spread her message. After one workshop in Bilbao, Spain, Fernando de Pablo, a participant from Madrid who had long followed Brown’s work on social media, decided to become a graphic entrepreneur himself, quitting his job as a designer at a retail bank two years later. He has since trained Spanish teachers in visual thinking and designed infodoodles for Greenpeace and Unicef as well as some private companies.

“I’m sowing my own competition,” Brown said. “But that’s how business works.”