In retirement, Fred Akers seemed to achieve the inner peace that often eludes college football coaches. To watch him sail around banquet rooms from Beaumont to Austin to El Paso, with smiles and handshakes and small talk for all those Longhorn fans, to hear him linger on memories of the miles and miles of games and recruits and heartbreak and joy, Akers could have passed for the happiest man on earth. By almost any measuring stick, but especially that one, his was a life well lived.

Akers died Monday at 82 of complications from dementia. Long before his health began to fail, he’d reached a comfortable place with who he was and, perhaps more important, who he wasn’t. That latter part is simple: he did not win a national championship during ten seasons as the University of Texas Longhorns head football coach.

No shame in that. Besides Darrell Royal and Mack Brown, no other Texas coach in the last 127 years has won it all, either. Problem is, Akers came close. Twice. Oh, so close. Close enough to touch it and feel it and taste it.

Two losses changed the course of his career at Texas. In one of them, a late turnover decided it. A muffed punt, of all things. Think about that for a moment. Roll it around in your brain.

Had the Longhorns won those two games—or even one of them—Akers might have stayed at Texas forever, had a statue erected in his image, and maybe a street named after him. At the very least, there’d be a Fred Akers lunch special at El Rancho. His legacy would have been that he took over for Darrell Royal, the greatest Texas coach ever, and led the program back to the highest level. Yes, those losses—to Notre Dame in 1978 and Georgia in 1984, both in the Cotton Bowl—gnawed at Akers, at least for a while. Eventually, though, he reached a point where he could focus more on what he’d accomplished at Texas than what he hadn’t. Remember: Akers did not lack confidence.

I covered Akers and Longhorn football for the Austin Citizen, Dallas Times Herald, and Fort Worth Star-Telegram in the late seventies and early eighties, and back then, the coach didn’t come off as cocky in the way, say, Barry Switzer did. But Akers knew he was pretty darn good at what he did. He was 86–31–2 in ten seasons at Texas, with a winning record against Oklahoma and four top-ten finishes in the Associated Press poll. He won two Southwest Conference championships.

In some ways, Akers began his tenure at Texas in a terrible position. He broke the first rule of coaching: Never replace a legend. Yet Akers did just that in 1977, when he took over for Royal and assumed control of a program that had gone 5–5–1 the previous season and had fallen far behind some of college football’s traditional powers, particularly Oklahoma. But Royal’s handpicked assistant coach, Mike Campbell, was the successor preferred by restless Texas fans and football program power brokers.

Akers never blinked. He’d been part of Royal’s staff for nine seasons and understood the demands of the gig. His discipline was unshakable. He’d been a four-sport star in high school, and despite growing up poor in Blytheville, Arkansas, and picking cotton for a time, he had a quiet swagger about him. As an athlete, Akers chose a football scholarship at Arkansas over a basketball ride at Kentucky. He’d been a high school head coach in Edinburg at 24 and took over the Longhorns at 38.

His traditional style, which some viewed as dull, was relentlessly consistent and comforting. He was a stickler for details who hated cluttered desks and unpolished shoes. Such clutter, he believed, reflected a mindset that would reveal itself—to disastrous effect—on game days. On the recruiting trail, Akers would walk into a prospect’s house, shake everyone’s hand, look each person in the eye, and invite some eighteen-year-old to join the Texas family. He wasn’t folksy, like Royal, who could work a room like nobody’s business.

Akers, however, didn’t try to emulate his predecessor’s charm. In ten seasons at Texas, Akers appears never to have uttered a memorable or controversial quote. His former defensive coordinator, Phil Bennett, told the Austin American-Statesman that Akers “was absolutely one of the finest and most balanced human beings I’ve ever been around, besides being a Hall of Fame coach.” Once, when Southern Methodist University coach Ron Meyer lost his place during a speech and quipped, “Excuse me a Fred Akers moment,” we reporters ran to Akers for reaction and got nothing. Well, we got one thing: Texas 30, SMU 6.

Months later, when someone brought up Meyer’s quote, Akers may have smiled. Years later I asked him about that game, and he still wouldn’t bite. He may have smiled at the memory, but maybe that’s just how I choose to remember it.

His strength was not in Xs and Os, although he was plenty good at both. His strength was not in hiring good coaches, although he did a good job there too. More than anything else, Akers understood how to build a winning culture. He did that with a singular, steely, and unwavering focus: all that mattered was winning that day, that week, that game. “He was one of those guys who, over the years, you realize that part of your lifestyle is based on things you learned from him,” Doug Dawson, an All-America offensive lineman, told the Houston Chronicle. “I call it ‘delusional optimism’—the ability to visualize success at every level.”

Donnie Little, who became the first Black quarterback to start for the Longhorns, told the Chronicle: “You could feel his honesty when he was sitting [in] our living room with my parents. He was preaching how he wanted to make change and make history at UT, and he was a man of his word.”

One Friday afternoon before a game against Rice, I sat in Akers’s office and began asking questions about the following week’s game against Oklahoma. These questions did not anger him. He simply could not comprehend thinking about Oklahoma when he was only thinking about Rice. I pestered for a bit, promised not to use any of the quotes until the following week, did everything I could to persuade the coach to look past lowly Rice and ahead to the next week’s opponent. He wouldn’t do it. Akers believed that if he allowed his focus to veer from Rice for even a second, his players might pick up on it.

Finally, grudgingly, he walked over to a photograph of the Longhorns coming down the tunnel for an OU game and pointed. “Look at their eyes,” he said. “Tells you everything.” In the photograph, the players’ eyes—open wide, nervous, thrilled—made it clear that the Longhorns needed no extra motivation against the Sooners.

When Royal retired after the 1976 season, Texas fans wanted Mike Campbell, Royal’s longtime defensive coordinator, as the next coach. Not Akers. But some at Texas—notably Allan Shivers, chairman of the UT System Board of Regents, and former chairman Frank Erwin—favored a clean break from the past. Akers represented that, sort of. He was 38 and had just led the University of Wyoming to an 8–4 season, Western Athletic Conference Championship, and Fiesta Bowl appearance. Wyoming was not a destination job for a head coach with big dreams, but Akers made it just that. “You have to figure out what you’re going to sell to kids,” Akers said. “What we figured out is that if you’re an inner-city kid, say, from Chicago, and you come to Laramie for the first time, you’re seeing mountains and natural beauty you’ve never seen before. You wouldn’t believe how many kids would be sold on us when they saw the place.”

Akers may not have been the first choice of Longhorn fans, but he established instant credibility by scrapping Royal’s beloved wishbone offense and making Earl Campbell the centerpiece of an I-formation scheme. The Longhorns opened the Akers era by beating Boston College, Virginia, and Rice by a combined score of 184–15, then beat three ranked teams—Oklahoma, Arkansas, and Texas Tech—in a four-week stretch. Texas topped the Associated Press poll after the Tech win and finished the regular season with a 57–28 win over Texas A&M. Before that game, Akers whispered to Campbell, “If you give me 120 yards, I guarantee you’ll win the Heisman Trophy.” Campbell rushed for 222 and won the Heisman a few weeks later. Then came a 38–10 Cotton Bowl loss to Notre Dame.

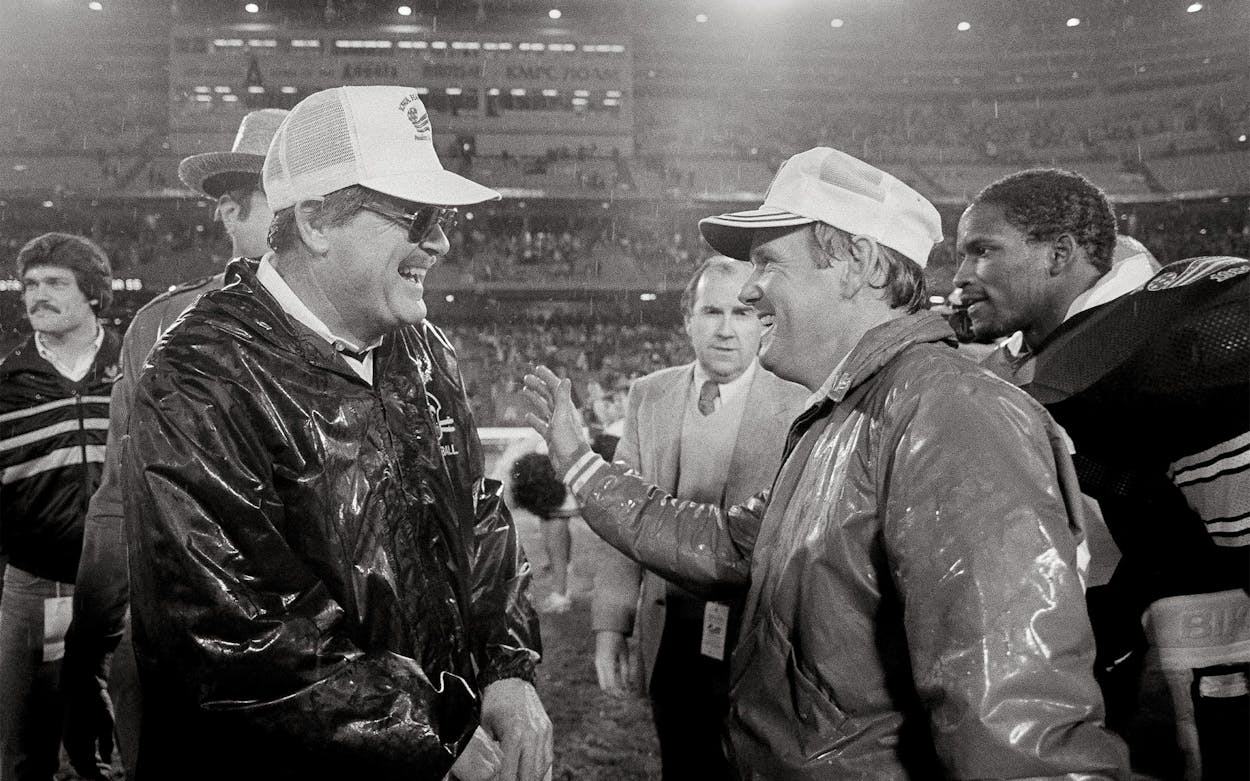

Six years later, in 1983, the Longhorns were again unbeaten and flirting with a National Championship until a 10–9 Cotton Bowl loss to Georgia that turned on a fumbled punt. Akers lasted three more seasons before being pushed out after a 5–6 campaign in 1986. At a time when recruiting violations were a way of life in the Southwest Conference, Akers left Texas with his reputation intact and finished his career with four difficult seasons at Purdue, where he went 12–31–1. Afterward, he returned to Austin, worked on his tennis game, and became a sought-after speaker on the informal University of Texas banquet circuit. By the time he settled into this life, Texas fans had come to cherish the Akers era.

Reputations are like that. They’re breakable, but they’re also bendable. Fred Akers did not win the big one, but he won plenty. He treated people the way everyone wants to be treated. As legacies go, that’s a pretty good one.

- More About:

- Sports

- Obituaries

- Austin