Soon after its 1956 release, the ranches-to-oil-riches-epic Giant assumed its place in the Texas film canon, but it might have just as easily fallen flat with local audiences. Though the 1952 novel of the same name was a best-seller, it raised the hackles of Lone Star Staters who felt that New York author Edna Ferber had disrespected their culture, especially in sections of the book critical of Anglo Texans’ contemporaneous discrimination against their Mexican American neighbors. When director George Stevens, from California, took on the film adaptation, he worried that he would be run out of the state on a rail. As he joked during preproduction, “The story’s so hot and Texans object so hotly, we’ll have to shoot it with a telephoto lens across the border from Oklahoma.”

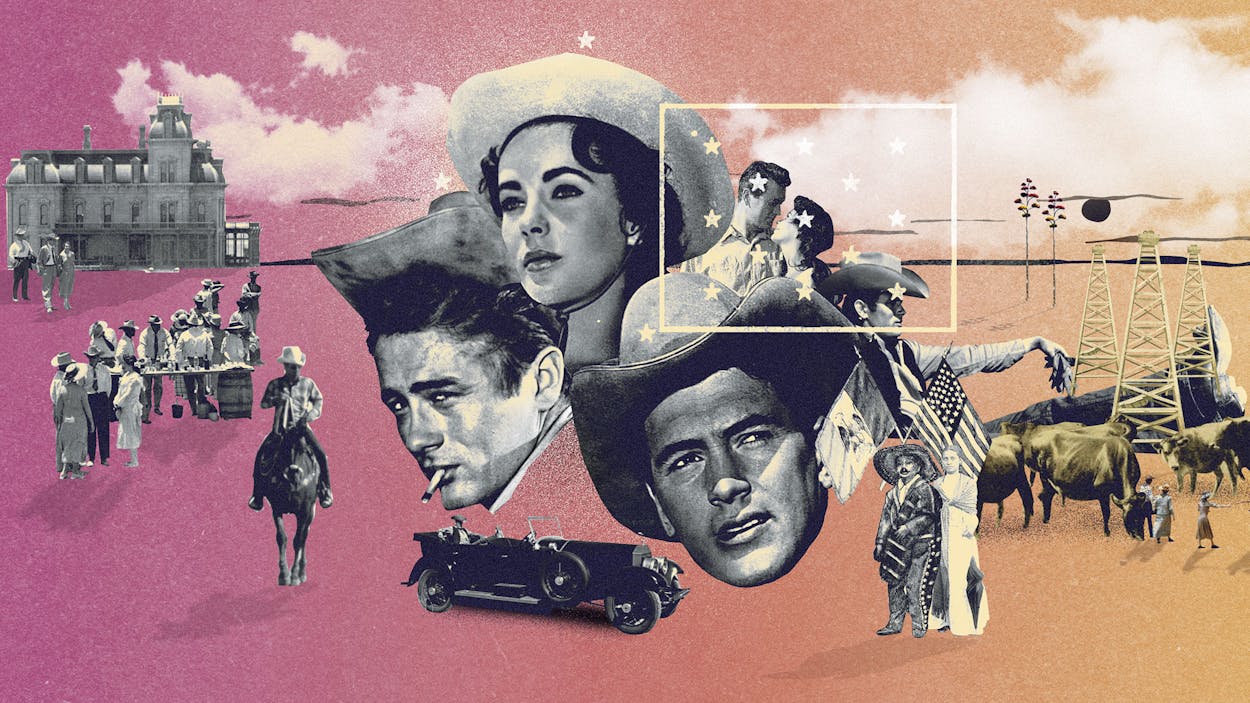

That quote, along with many that are equally memorable, was unearthed by University of Texas at Austin English professor (and Texas Monthly contributing editor) Don Graham, author of the new, comprehensive history Giant: Elizabeth Taylor, Rock Hudson, James Dean, Edna Ferber, and the Making of a Legendary American Film (St. Martin’s Press, April 10). Graham is the first to collect all of the film’s larger-than-life tales in one place: the lore of James Dean’s iconic final performance, the relationship push-pull between the three lead actors, the impact of the star-studded production on the tiny desert town of Marfa. But the most compelling narrative in Graham’s book, which comprises three years of writing and poring through archives and stacks of Hollywood memoirs, follows how a film so hostile to old-fashioned Texas values managed to impress itself so deeply upon a state that doesn’t take kindly to lectures from outsiders.

That aspect of the story begins with Stevens. One of Graham’s favorite parts of researching the book was learning about the accomplished director, whose 1951 film A Place in the Sun won six Academy Awards. Stevens joined the U.S. Army Signal Corps during World War II, shooting footage of D-day and Nazi concentration camps. When he returned to the U.S., Stevens became interested in the civil rights struggle, particularly the bigotry and inequity suffered by Mexican Americans. “[Stevens] wanted to rub Texans’ nose in this kind of prejudice,” Graham says in an interview. “What he’d seen in the camps, what he’d seen in Europe, he didn’t want to happen over here. He didn’t want this kind of second- or third-class citizenship.”

Stevens’s mission is most clearly manifested in the moral trajectory of Bick Benedict (Hudson), a wealthy Texas rancher. Thanks to the influence of his East Coast–born wife, Leslie (Taylor), Benedict’s attitudes toward his state’s caste politics shift as the film progresses. In Giant’s penultimate scene, Benedict displays his growth by standing up for a Mexican family after they’re refused service at a roadside diner; the film ends with a shot of two Benedict grandchildren side by side, one Anglo and one half-Hispanic, seemingly divining a future Texas.

Giant’s rare-for-the-time depiction of racism had a real effect on the state. “Mexican Americans had a rough time of it in Texas in that period. There were Texans during that time that didn’t know that,” Graham says. “They didn’t realize, because they didn’t live in San Antonio, South Texas, or West Texas.” As Graham sees it, there’s a Texas-size parallel between Benedict’s unlikely evolution into a civil rights defender and the real-life story of Lyndon Johnson, a conservative senator who went on to sign key civil rights legislation, in the sixties. The arc of Hudson’s character and of U.S. history both bend toward justice, one just a few years after the other.

Benedict’s slow path to enlightenment may have foretold a change in national attitudes, but it’s difficult to imagine Giant becoming an object of what Larry McMurtry called Texas’s “blind love” if not for Dean’s portrayal of the ranch hand turned wildcatter Jett Rink. Graham, who first saw the film as a teenager in Dallas in 1956, knows that appeal well. There’s a scene early in the film where Rink has just, to the surprise of Benedict, been willed a small section of the family’s enormous ranch by Benedict’s sister, Luz. Benedict tries to buy him out, but Rink says he’d prefer to keep the land and “gamble on with her.” As Rink leaves the ornate office of Benedict’s massive Reata ranch home, he gives a funny sort of flat-handed wave. It’s a cool, take-no-crap gesture, and teenage Graham adopted it for himself. “I’ve used that all my life, and I got it from James Dean,” Graham says.

In Graham’s recounting of the production in Marfa, Dean is the impish antihero set on not only stealing the spotlight with his performance but also capturing the affections of the world-renowned beauty Taylor from both her second husband, Michael Wilding, and her platonic Marfa drinking buddy Hudson, who was intensely jealous of Dean’s star power. Both Hudson and Dean had relationships with men throughout their lives, but in Marfa they mostly tussled over Taylor. “I was very connected to them, but it was like on the left side and the right side,” Taylor would later say of her co-stars—a tantalizingly geometric metaphor that somewhat mirrors what we see on-screen. “I was in the middle, and it just would be like a matter of shifting my weight.”

In the Land of Giant

The sprawling Ryan Ranch, where Giant was filmed, is more than twice the size of Manhattan.

When he wasn’t busy trying to win over Taylor, Dean took maximal advantage of the resources provided by Stevens in order to seduce Texas audiences. The director brought in a dialogue coach (real Panhandle rodeo cowboy Robert Hinkle, listed on the payroll as “Texas Talk Man”) and, most importantly, fought to shoot the film in Marfa. While Hudson and the others were off drinking martinis, Dean hung out with local cowboys, spending hours mastering rope tricks and mannerisms.

All that work paid off. Dean succeeded in taking a cautionary-tale subplot—a workingman transformed by oil wealth into a drunk, racist, newly rich playboy—and elevating it to a Texas tragedy that cuts against the noblesse oblige lesson of Benedict’s transformation. Even if Leslie succeeded in civilizing her husband, Dean’s performance shows us that there will always be someone else, someone even more ruthlessly acquisitive, eager to take his place. The self-immolating ardor Dean brought to Rink became his final screen legacy. Three weeks after completing his last scene in the film, a rambling, drunken soliloquy to nobody, the 24-year-old Dean died in the wreckage of his Porsche.

As Graham points out, traces of Dean and Rink pop up everywhere in latter-day Texana, as the comical and very Rink-like oilman J. R. Ewing, in Dallas; in the Dean-obsessed play and film Come Back to the 5 and Dime, Jimmy Dean, Jimmy Dean; and even in a pivotal scene in the biopic Selena. Our long-standing devotion to Rink suggests that perhaps 1950s Texas audiences were won over less by Giant’s proselytizing lesson of tolerance and more by Dean’s wild id—a scene-stealing, method-acted incarnation of Texas thirst for love and property that scuffed up Stevens’s intended moral.

“Oil is supposed to be bad in the film,” Graham says. “Historically, oil is always bad in Texas culture. But Jett Rink is the guy we like the most. When he strikes oil, he says, ‘I’m going to have more money than you ever thought you could have. You and all the rest of you stinking sons of Benedict.’ I never forgot that scene when I was a kid.”