There was a time when John Graves, who died Tuesday at 92, was not the serene and towering elder statesman of the Texas literary world. But to people of my generation who knew him it was hard to picture him when he was young, when he was just another desperately self-conscious beginning writer, doing the Hemingway thing in Europe, hanging out in cafes and fishing in trout streams and taking careful notes in the bull ring about the matador’s skillful veronicas.

John Graves—so assured, so stately, blind in his left eye from a Japanese grenade on Saipan—could never, even then, have been a cliche. But it is heartening to think that he might once have been as uncertain as the rest of us, that his majestic self-possession was something he had to earn and grow into.

“During none of this period,” he wrote in Myself and Strangers, his memoir about his postwar expatriate life, “was I in the middle of important things that were happening, whether literary, political, or otherwise. . . Nor has being outside the middle ever bothered me much.”

The self-deprecation is characteristic of Graves, and so is the confidence. He created his own middle. He published Goodbye to a River in 1960, after giving up on the novel he had gone to Europe to write. The book was about a canoe trip he took with his dachshund down a stretch of the Brazos River before it was scheduled to disappear behind a dam. It could have been just another forgotten environmental lament, just another fieldish-and-streamish travelogue, but it made John Graves a major American writer. Part elegy, part history, part nothing-anybody-has-ever-quite-figured-out, it sets its pace and throws down its casual authority in the first sentence:

“Usually, fall is the good time to go to the Brazos, and when you can choose, October is the best month—if, for that matter, you choose to go there at all, and most people don’t.”

You enter Graves’s narrative in the same way his canoe enters the water—with barely a sound. But then his prose effortlessly carries you off. Sometimes it riffles along with straightforward motion, but just as often it casts off eddies of subordinate clauses that circle and circle but always lead back to the main channel.

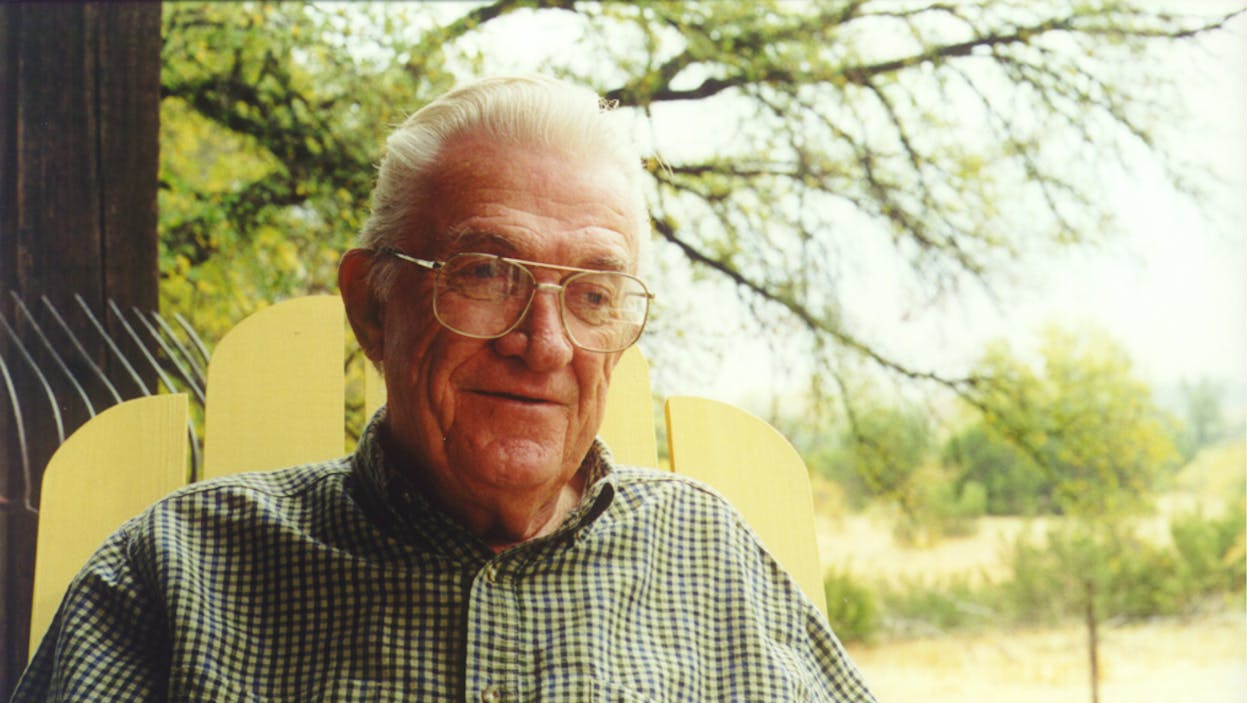

John’s writing voice was his speaking voice—mellifluous, a little mumbly, relaxed, telling you things without trying to sell you on them. His head always seemed to be tilted slightly down, so he could look up at you and inspect you with his working eye. He smiled slyly as he talked, giving the impression that you and he shared some secret knowledge. He told stories and jokes and laughed at stuff but mostly he seemed to want to listen. He spoke when he had something to say, never when there was merely a silence to fill. There was nothing particularly intimidating about him but I found myself always carefully husbanding my words in his presence, not wanting to feel gabby and excitable by contrast. You always felt that, in some quiet way, he was measuring you and recording your worth.

In his long career he produced only a handful of books, and from time to time he indicated that he felt troubled about that, or at least sheepish about it, but I think it only bothered him because it seemed to bother other people. If he had wanted to write more, he would have.

He lived his life, as far as I can tell, indifferent to the expectations of his readers and publishers, undistracted by literary fashion, uncorrupted by the need to please. For the most part, he was a chronicler of a world that had already passed away, or was passing away as he wrote about it. About this he was nostalgic but not sentimental, rueful but not angry. He lived long enough to see a mild backlash—his immaculate sentences could seem fussy to some, his rear-view vision of an agrarian, hardscrabble, undammed Texas irrelevant to others. But if you’ve read and loved Goodbye to a River, or Hardscrabble, or From a Limestone Ledge, you don’t feel the need to defend them. The books made their own case long ago.

When John Graves was roving around Spain as a young man, feeling “Destiny sitting heavy on my shoulder,” he found himself in Pamplona for the San Fermín festival. “I saw Papa Hemingway,” he wrote in his memoir, “holding court at a sidewalk table on the main square, and using his sport coat as a cape while still another collegiate American served as bull and charged him.”

One by one the young acolytes in the plaza walked up to Hemingway to shake his hand and say a few words to him, but John Graves held back.

“I had not yet proved myself as a writer, a real one, and until I managed that I didn’t feel I had the right to impose myself on established authors, however much I might admire their work.”

It’s an introduction long overdue: Mr. Hemingway, meet Mr. Graves.