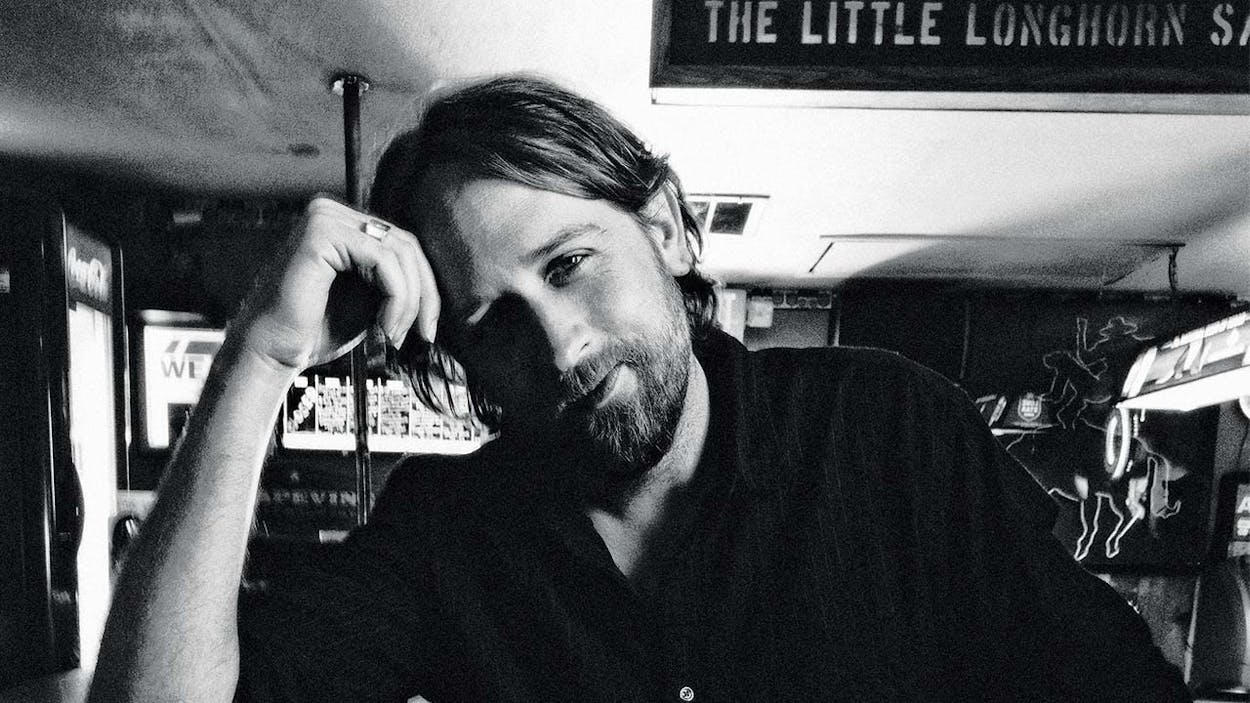

On a recent Sunday afternoon, a few hours before the crowds started showing up for Chicken Shit Bingo at Austin’s Little Longhorn Saloon, a twelve-year-old magician worked one side of the room. “Watch these four aces,” Eli Carll instructed us, as he held four cards in his hands. One at a time, each card reversed itself, somehow flipping from front to back. The last time, he snapped his fingers over the cards, they did something completely inexplicable, suddenly transforming into four kings. The trick is called Mercury Aces, and when Eli looked up from the deck at his audience, you could see him savoring our reaction.

“When he was just seven, he told me, ‘I live for the look of amazement on their faces,’ ” says Eli’s father, Hayes Carll, the much-loved Austin singer-songwriter. “As a performer, that resonated with me.” Occasionally, Carll drives his son to Austin’s South Congress Avenue to perform street magic for passersby. “He wasn’t always good at it. The tricks didn’t always work. But he’d bomb and try again. And again. He’s become so amazingly committed to chasing that moment where he blows somebody’s mind.”

Eli’s persistence—and the confidence he found in magic—is the obvious inspiration for “The Magic Kid,” the most striking and lyrically direct song on Carll’s new, self-released album, Lovers and Leavers. “You shine your light for everyone to see / The only one I’ve known who’s truly free,” he sings tenderly, his voice on the verge of cracking. Carll wrote the song in early 2013 in Nashville with songwriter Darrell Scott. The first person to hear it outside of the writers’ room was his son. “I flew back to Austin late that evening and crawled into his bed to say good night,” Carll says over coffee at Austin’s Central Market, fighting back tears, pausing between sentences, apologizing for nearly breaking down completely. “I played him the demo on my iPhone. He cried. And I cried. And it felt really good for me to know that he could see how proud of him I was.”

Though “The Magic Kid” is clearly for Eli—a lot of folks’ Father’s Day playlists just got one song longer—the bulk of Lovers and Leavers is made up of songs that reflect Carll’s own struggles. The emotional core of the record—his first in five years, an eternity for a working musician—is the turbulence he’s recently experienced in his personal and professional lives. About halfway through that five-year gap between albums, Carll’s marriage to Eli’s mother, Jenna, became irreconcilable. Around the same time, he dramatically cut back on his whiskey consumption. He came to realize that booze was something he was hiding behind onstage and too easy of an excuse for the bad decisions he was making offstage. And not long after that, he recognized his career was in coast mode, that however successful playing two-hundred-plus shows a year may have seemed, the sheer repetition of it all had extinguished his curiosity and drive.

“I’d stopped evolving,” says Carll. “I was bored creatively and getting depressed about it. If I didn’t push myself now, I knew it was going to be harder and harder to do later. And I knew if I was going to do that, I’d need to shake free of my comfort zones. I knew that in twenty years, I didn’t want to be playing the same twenty songs for people every night, knowing exactly the kind of reaction each one would get, while I’m up there secretly, slowly dying inside.”

The drinking, which was partly a response to his restlessness, only exacerbated the situation. “Being a traveling party takes a toll physically, and for me, psychically. I kind of lost who I was,” Carll says. “My drinking got progressively worse, almost second nature. When you’re bored and not challenging yourself, you have to find a way to make it interesting. If I drank enough whiskey, I could fool myself into feeling my lyrics and feel like I was connecting in a profound way.” It didn’t help that Carll, like so many performers, and so many drinkers, is actually shy and self-conscious. “If I tap my foot, that’s an exuberant display. So with a big, rowdy crowd, though I’m sure I didn’t look very cool, booze certainly helped me feel cool in the moment.”

Carll may have drunk excessively for confidence, but he also thought it gave him authenticity. Though he has lived in Austin since 2006, he grew up in The Woodlands, the Houston-area master-planned community with more golf-cart crossings than bars. When he was fifteen, he told his mother he wanted to be a country singer. “What are you gonna sing about, how there’s no towels at the country club?” she asked him.

“I didn’t want to be a suburban pop singer in a turtleneck,” he says. “I wanted to be seen as Guy Clark or Jerry Jeff Walker—a wild, smoking, drinking cowboy. Music and Kerouac opened my eyes to pool halls, bikers, and shady characters. Those things weren’t part of my upbringing. I didn’t know how to get to them. But I knew I needed to find it.”

After he graduated from Hendrix College, a small liberal arts university in Arkansas, Carll made a concerted effort to find the people who had fascinated him as a teenager. He set up shop along the Bolivar Peninsula—home to a series of beach towns that have long been a notorious magnet for drifters and outlaws—and grew certain that what he calls “the drunken poet path” was the only path.

“For a long time, I thought it was less genuine if I wasn’t that character, that there was some authenticity that came from being the drunken rambler, the singer-songwriter who has the respect of other singer-songwriters and maybe not much of an audience beyond that,” Carll says.

Early in his career, Carll figured out that one way he could maintain an audience was by relying on volume and humor. At Crystal Beach bars, he learned to play loud to get a crowd’s attention and, hopefully, keep them dancing. And at Galveston’s legendary listening room the Old Quarter, where he opened for acts like Ray Wylie Hubbard, Shake Russell, Willis Alan Ramsey, and Steve Fromholz, Carll quickly learned that the best way to earn attention from an audience that doesn’t know your songs was with humor, often of the self-deprecating variety, both in his songs and in the stage patter between.

On his last record, 2011’s KMAG YOYO, loud and funny came together in the form of a much-quoted declaration: “I’m like James Brown only white and taller/ And all I wanna do is stomp and holler.” The album, named for the classic military acronym “Kiss My Ass Guys, You’re on Your Own,” was pretty much his breakthrough, appearing on best-of-year lists at Rolling Stone, Spin, and American Songwriter. This year, Lee Ann Womack’s version of a song from the record, “Chances Are,” was nominated for two Grammys. Carll says a quick follow-up album was tempting, but after leaving his label, Lost Highway—the largely Americana-focused Universal imprint that included Willie Nelson, Ryan Bingham, and Lyle Lovett on its roster before dissolving—and dealing with his impending divorce, time got away from him. Though he worried that fans would forget him if he waited too long, that fear was outweighed by his resistance to making a KMAG YOYO retread. And even as he watched similarly minded artists like Jason Isbell, Chris Stapleton, and Sturgill Simpson clear a path to mainstream success, Carll says the time away made him less interested than ever in hoping one of his songs might get radio play or that a handful of loud and upbeat numbers might liven up his live set.

“For the first time I didn’t consider any of that at all,” he says. “This time, I had the songs and said, ‘This is what it is.’ I wish that was something I could have done earlier in my career.”

So by design he neither stomps nor hollers on Lovers and Leavers. It’s uniformly quiet and mostly acoustic; there are no electric guitars, only a fairly minimal deployment of pedal steel, percussion, piano, and not much else. “I wanted there to be space and room to breathe,” he says. Equally by design, Lovers and Leavers is short on laughs. As in there are none. And there’s nothing remotely like his 2008 song “She Left Me for Jesus,” which may not be the best country song ever written, as Don Imus once suggested, but is certainly one of the funniest.

“Writing from a personal place always made me feel really exposed,” says Carll. “So I’d distract people with sleight of hand—it’s always been a lot of ‘Now look over here. Let me make you laugh.’ I could hide behind that laughter. Making ’em laugh, making ’em cry, and then shifting back felt safe to me. But I think after the divorce it wouldn’t have felt real to come out cracking jokes and one-liners. For the first time, I didn’t feel like I needed that distraction.”

The bulk of Lovers and Leavers is written in the first person. If you know the backstory—the divorce and that he’s found love again, with singer-songwriter Allison Moorer, herself recently divorced, from Steve Earle—the songs about love lost and love found sound autobiographical. (Expect reviewers to make a lot of comparisons to Bob Dylan’s Blood on the Tracks.) Out of respect for his son, and because it’s not his style anyway, Carll isn’t talking about the divorce, his relationship with Moorer, or what songs each may have inspired. He knows people will try to guess which tunes are based on his life and which are products of his imagination and says only, “Some are confessions, some are just characters making confessions.” But he admits that there’s probably a direct connection between the sobriety of the record and his decreased alcohol intake.

“Partying constantly was romantic for a long time, maybe too long,” Carll says. “But that’s not who I want to be now. I can be an artist without having to be the drunken guy who’s up all night at every party.”