One overcast December morning at the 7W Youth Riding Club stables, in Tomball, Myrtis Dightman Jr. peers out from the brim of his black cowboy hat. “Mr. Myrtis,” as he’s known around the ranch, watches a group of children, most of them under ten years old, brushing bits of straw from their horses’ chestnut-colored coats. Among them is two-year-old Wynter Wilkins. Wearing a pink cowboy hat, she excitedly blurts out her horse’s name: “Summer!” Her grandfather, Larry Wilkins, scoops her up and places her in the saddle. Four members of the riding club—Major Wilson and tween siblings Javian, Jammarian, and Jayden Henderson, who have been riding horses since they were Wynter’s age—look on as they prepare to saddle up.

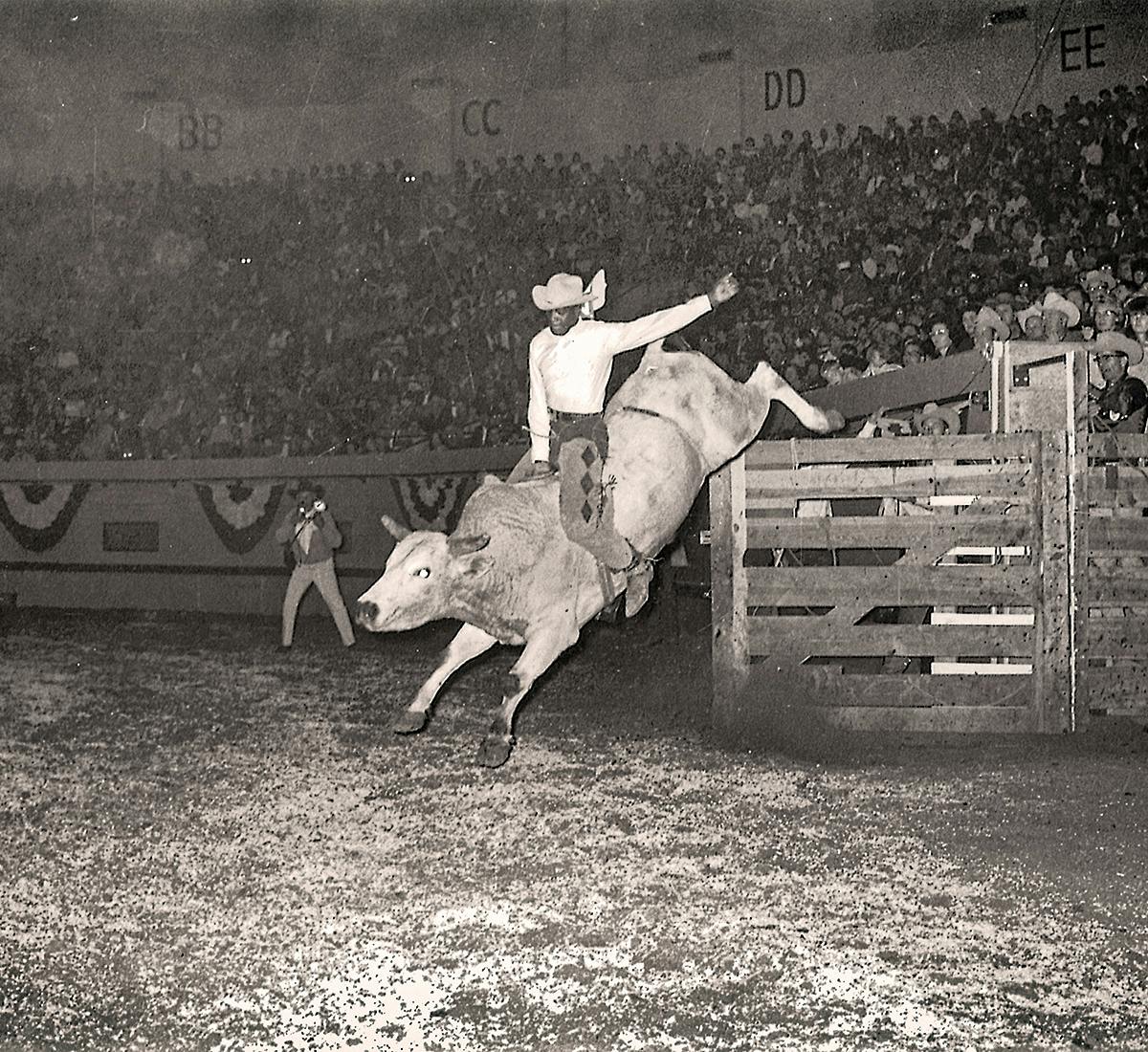

Dightman Jr.’s life in the saddle was practically predestined. His father, Myrtis Dightman Sr., is a Hall of Fame bull rider who broke the color barrier in 1964, when he became the first black cowboy to compete in the National Finals Rodeo. Nicknamed “the Jackie Robinson of Rodeo,” Dightman Sr. spent decades on the circuit, often qualifying for competition by riding the roughest bulls of the lot.

Like many of his students, the 64-year-old Dightman Jr. was a toddler when his father first plopped him on a horse. Growing up in the seventies, on his father’s ranch in Crockett, he rose early to feed his cow and pigs each morning, taking care that his boots were cleaned of any muck before he headed to school. His classmates, many of whom were also black, teased him. “When you’re black and you wear cowboy boots and Wranglers, you’d get called a goat roper and told you smelled like shit,” he says. “They’d ask me, ‘What kind of black man rides a bull?’ ”

As the trail boss of the Prairie View Trail Ride Association, named for the historically black university, Dightman Jr. has made it his mission to ensure that future generations of black children appreciate the patience and labor that go into being a cowboy. Since its founding, in 1957, the association—composed of seven local trail groups, including the 7W Youth club—has helmed Texas’s oldest African American trail ride, an annual 88-mile procession running from Hempstead to Houston. Along with several other trail rides, it signals the beginning of the annual Houston Livestock Show and Rodeo.

The Houston Rodeo, which takes place this year from March 3 to 22, held its first trail ride in 1952 and included only 4 men on horseback. The following year, 80 people signed up to participate in the first Salt Grass Trail Ride, the route still known as “the granddaddy of ’em all,” which traces a path from Brenham to Houston. Other groups from across the state began riding to the rodeo. These days, more than 3,000 riders from twelve separate trail riding groups cover over 1,300 miles en route to Houston. Last year, the PVTRA’s caravan of roughly 250 included riders on horses, plus mules and wagons.

The group, which also does trail rides year-round, began gearing up for this year’s rodeo in early November, beginning with wagon inspections. The unwieldy wood-framed vehicles that carry the cowboys’ gear for the journey are susceptible to termites and wood rot, and repairs must often be handled by specialists. In the weeks leading up to the rodeo, the 7W Youth Riding Club meets more frequently, and participants start to “leg up” (cowboy talk for “warm up”) their horses in preparation for “the big ride.”

On Sunday, February 23, the cowboys will roll out from Hempstead toward their first stop on the six-day journey to the rodeo: Prairie View A&M University. This first leg—between thirteen and fifteen miles—is intentionally short; that way, the riders can confirm everything is in shape for the rest of the journey. Over the next few days, they’ll visit local schools (many kids in the PVTRA get permission to take off school that week), teaching students about the group’s history. In the event’s 63 years, traditions like a joint chili cookoff with Prairie View A&M and a dance contest with members of the Community of Faith Church, on the north side of Houston, have become an important part of the trail ride. Dightman Jr. says that along the way, passersby often stop at the campfires to enjoy food and conversation with the trail riders. He jokes that it takes a month to get the smoke from the campfires out of his nose but that the plentiful helpings of barbecue, fried fish, and cowboy stew are worth it.

The trail is very different from the one the Old West cowboys traveled, and it’s certainly not the trail of Dightman Sr.’s days either. Since the Prairie View trail riders first rode into the Houston Rodeo in 1957, their longtime route and campsites have adjusted to accommodate new highways and neighborhoods. Their horses, like Dightman Jr.’s palomino, Blondie, have been trained to cope with things like traffic. “It’s one thing to ride a horse, but to train it to deal with all the noise from trucks and cars is something else,” he says. “You’ve got to pay real close attention. Things can go wrong quickly.”

While black cowboys have been around since before the beginning of the cattle-driving era, they haven’t always been visible. By visiting elementary schools and a historically black university along the way, these cowboys have a chance to tell their stories and to issue a corrective to the reductionist narrative that pop culture has long perpetuated about who cowboys really were.

During the late nineteenth century, at the height of cattle driving’s popularity in the United States, about one in five cowboys was Hispanic, black, or Native American, says Michael Grauer, the McCasland Chair of Cowboy Culture and Curator of Cowboy Collections and Western Art at the National Cowboy and Western Heritage Museum, in Oklahoma City. (Other historians have placed the estimate higher.) Those numbers vary considerably depending on location. In the Rio Grande Valley, most cowboys were Mexican, while those working along the Gulf Coast were predominantly black. In states like Oklahoma and the Dakotas, many cowboys were Native American.

According to Grauer, cowboy traditions originated in Africa, where cattle herders would rope cattle on foot, and the likes of the Maasai people drove them toward better lands for grazing. After the Muslim cavalry’s conquest of Spain, in the eighth century, these traditions made their way to Europe and eventually moved to North America in the early sixteenth century, during the colonization of Mexico.

In the Civil War era, enslaved people developed horse-training and cattle-tending prowess, and they became known for their bronco-busting abilities, while Hispanic vaqueros’ skills with a rope were unmatched. Then a booming demand for beef in the northern states sparked the cattle-driving period in the 1860s. Cattle drivers held friendly competitions that eventually transformed into contests between crews from different ranches, where cowboys duked it out to see who was the better rider or who was more adept with a lasso.

Cowboy Etymology

The word “buckaroo” points to the deep roots of cowboy culture. The word is said to be a bastardization of “vaquero,” the Spanish word for cowboy.

In the late 1880s, when the cattle-driving era had ended, Wild West shows sprang up to entertain crowds with a romanticized vision of the Old West. From the beginning, these shows, which often featured shooting competitions and battle reenactments, centered on primarily white characters. Black, Hispanic, and Native American actors were given few roles—most frequently, they were tapped to add an “exotic” element to the story, says Grauer. Regional rodeos also cropped up throughout the South, with Pecos, Texas, holding claim to the first.

The Houston Stock Show and Rodeo, the world’s largest livestock show, debuted in 1932 (the parade and organized rodeo portions were added in 1938). For years, many of its qualifying events were off-limits to black riders, who were often barred from participating and struggled to get sponsorships. When they did compete, they were often unfairly scored.

In 1957 Dightman Sr. and his friend James Francies Jr., frustrated by this mistreatment, started their own trail riding group, which became the Prairie View Trail Ride Association. When they first went to the Houston Rodeo that year, they were only about ten riders strong. The night before the parade, they camped out on a nearby hill, away from the white cowboys’ campsites at Memorial Park. As associate editor Christian Wallace wrote in these pages in his July 2018 profile of Dightman Sr., the following day the group was forced to ride several blocks behind their white counterparts.

Despite the hostility they faced, the group carved out a path for other marginalized groups of cowboys, such as Los Vaqueros, a Hispanic organization that was founded in 1974, whose trail ride to the Rodeo stretches from Hidalgo, in the Rio Grande Valley, to Houston. “I don’t think my dad realized what he was doing,” Dightman Jr. says. “He thought he was just competing against the bull; he didn’t realize he was up against the bull, the judges, and the whole crowd too.”

Inside the Black Cowboy Museum, in Rosenberg, located about 35 miles southwest of Houston, is a picture of Myrtis Dightman Sr., along with news clippings, belt buckles, and saddles that once belonged to black and Hispanic riders. Larry Callies opened the museum in 2017 to commemorate the unsung heroes of the Southwest, such as the Taylor-born Bill Pickett, a black cowboy who wowed crowds in the early twentieth century by busting seemingly “unbustable” broncos; he also invented bulldogging (or steer wrestling), which is now a staple of professional rodeo events.

Though it’s only three years old, the museum has its roots in the historic George Ranch—a 22,000-acre property and one of the original “Old Three Hundred” land grants given by Stephen F. Austin—located right outside Houston. While working there as a cowboy from 2011 to 2014, Callies came across a pile of items left out for trash, including photos, booklets, and pamphlets featuring black cowboys, many of whom he’d never heard of. Callies says that for the first time in his life, he realized that people like him belonged in history books. “From the very beginning, black cowboys were left out of the story,” he says.

He started collecting whatever ephemera he could find, often in bookstores or from friends and family members who had a personal interest in cowboy culture or had been a part of it. Not everyone was receptive. “I’m not trying to get political,” he says with a smile. “People would get offended or run off when I would tell them the real story about black cowboys. But I’m just trying to tell the truth.”

Callies used his life savings to open the museum. Since then, he estimates, he’s welcomed several thousand visitors. For many of them, the word “cowboy” undoubtedly conjures up images of rugged heroes who dominated the American West with the help of a Colt Peacemaker and a trusty steed—and who were white. “From dime novels in the late 1800s to Wild West shows and films, the history of the cowboy became invariably very white,” Grauer says. Cowboy movies that did feature characters of color often cast white actors to play them. As recently as 2013, Johnny Depp was criticized for his portrayal of Tonto, a Native American, in Disney’s The Lone Ranger. Bass Reeves, the first black deputy U.S. marshal west of the Mississippi, is thought by many to have been the real-life inspiration for the Lone Ranger. But in eighty years of film and television adaptations, only white actors have been cast in the role.

A recent cultural shift has been changing that narrative. Reeves was recently featured in the opening scene of the HBO series Watchmen, which showed a young black child in Tulsa, Oklahoma, watching a silent movie that featured the character of Reeves vanquishing a corrupt town sheriff. The experience galvanizes that young boy to eventually become a superhero who battles against a white supremacist organization. And Bri Malandro, the Dallas native behind the popular Yeehaw Agenda Instagram account, has chronicled the way people of color, like Houston rapper Megan Thee Stallion and Lil Nas X, whose 2019 hit “Old Town Road” is the longest-running Billboard number one song of all time, are reclaiming Western fashion.

The ascendance of Megan Thee Stallion and Lil Nas X means that Dightman Jr.’s young riders have an entirely new generation of pop culture icons to look up to; “Old Town Road,” after all, made an anthem out of the line “I got the horses in the back.” Eighteen-year-old Ricky Reed, the oldest member of the 7W Youth Riding Club, worries that for some performers, dabbling in cowboy culture is just a fad they’ll eventually move on from. Regardless, he thinks they’ve helped advance the conversation. “The older I get, the more I see black people riding horses,” he says. “But to me, a cowboy isn’t just someone who rides a horse. You have to take care of it. You have to know how to ride it.”

That’s why Dightman Jr., much like his father, who is now 84, made sure to put his own son and his grandson on horses when they were toddlers. His grandson Myrtis Dightman IV, who is 13, is learning the ropes as the junior trail boss of the Prairie View Trail Ride Association. Come February 28, the cowboys and cowgirls will begin making their way to Houston’s Memorial Park, where they will participate in a parade procession with other groups of cowboys before the rodeo begins. “The tears start coming,” Dightman Jr. says, “because we know the trail ride is over until next year.”

- More About:

- Sports

- Megan Thee Stallion