texasmonthly.com: When and how did you first learn about Tourist Court Journal?

Anne Dingus: Don Sanders, of Dallas, tipped me off about the existence of this funky (and defunct) little magazine. In 1996 he and his spouse and co-author, Susan, were working on a book about a great and largely late American institution, the drive-in movie theater. Because I had once done an article about small-town movie houses, Don called me to see if I had happened to run across any good sources on drive-ins. During the conversation, he mentioned seeing an old-fashioned motel publication called Tourist Court Journal at Temple’s Railroad and Heritage Museum. He said, “You ought to do a story on it someday.” I tucked the suggestion away in the back of my mind and finally acted on it seven years later. Don, a thousand thanks!

texasmonthly.com: What is the difference between terms like auto camp, tourist court, and the like?

AD: Both the auto camp and the tourist court were early terms for what we now call a motel. The auto camp was the first incarnation, and its appearance was an inevitable result of the popularity of the automobile. Drivers began realizing they could motor, as they called it, not just around town or to a neighboring city but considerable distances, thus reaching places that weren’t the same ol’ destinations offered by trains. The auto camp sprang up to accommodate these travelers, because there were no hotels in places so newly designated tourist attractions. As the name implies, an auto camp was very basic; either guests slept in their cars or in plain cabins, and shared dining and bathroom facilities, much like kids do at summer camps today. Some historians believe that the nation’s first auto camp, or proto-motel, was established in Douglas, Arizona, as early as 1901—hard to believe that was more than a century ago. By the early twenties, however, travelers’ lodgings had become considerably nicer, and the term tourist court reflected this improvement. A tourist court usually featured miniature cottages, each with its own bath facilities. The little cabins usually formed a U and all faced an inner court with trees and flowers or perhaps a lawn with a croquet set or a barbecue grill. Guests parked outside the U, to preserve the gardenlike effect. In El Paso there was a famous place called Camp Grande, which was built in 1923 and which combined the appeal of both the older auto camp and the trendier tourist court. Guests there could rent, for only 75 cents, a covered but open-walled garage with room for folding chairs next to the Model T, or a “bungalette” complete with three tiny rooms and a bath. By the late thirties, a trendier term was motel, a shortened form of “motor hotel.” The motel was yet a different arrangement: a single building with rooms in a straight row or an L shape, which was a more-cost effective form of construction, and travelers parked their cars directly in front of their rooms.

texasmonthly.com: How did you research this story? Was it difficult to track down information?

AD: This story was a delight to research because all I had to do was sit down and pore over copies of the Tourist Court Journal. I called the Railroad and Heritage Museum in Temple and hooked up with Craig Ordner, the archivist there. He obligingly hauled the full set of Tourist Court Journal—some fifty bound volumes, spanning the years 1937 to 1969—from their shelves in a storeroom and set them up for me on a table in a quiet corner. I drove in from Austin early one morning, and he left me to it. There was no way I could look through all those issues—more than three hundred of them—so I started with the first full year, then skipped every three or four years and jotted down notes nonstop. The material was fascinating, in part because the publisher was a complete novice and his efforts were, at times, amateurish and stilted (albeit in a rather endearing way), and in part because the magazine was a mini-mirror of American life and values. It was fun to see the look of the magazine change—the dresses of the women in the ads, the color schemes favored in the motel rooms, the concerns of the couples who ran the inn and lodges. I started reading the volumes at eight-thirty in the morning, and at one point Craig stuck his head in and said, “Aren’t you hungry?” It was two-thirty. Six hours had gone by. (And, gee, was one part of me numb!)

texasmonthly.com: What was your favorite cover of Tourist Court Journal? Why?

AD: Ooh, it’s a three-way tie, and first I have to say that “favorite” means “funniest,” because few of the covers were what I would term attractive. The production quality was lousy—obviously there wasn’t a huge budget—and the images all seem so dorky now. My three favorites were all from the forties and early fifties. One was a photo of the interior of a motel room (the most common subject of TCJ covers), but this one was—at least to my modern eye—staggeringly ugly: dark green walls, dark blue cord bedspreads, a hideous gold-speckled beige lamp on a blond-wood nightstand along with a lethally heavy ceramic ashtray that was vaguely boomerang-shaped—and that was it. If that magazine had been offered on a newsstand, no member of the species homo sapiens would have bought it (except, possibly, for the can-you-believe-this value). Another wondrously awful cover showed a little girl in a cornfield—apparently because the theme of corn was related, at least thinly, to the issue month, October—but the photo was blurry, the child looked like the starved subject of a Dorothea Lange Depression-era photo, and the corn appeared to have been feasted upon by a horde of grasshoppers. In fact, the following month a letter from a Kansas subscriber to the Texas staff offered, tongue-in-cheek, to provide an attractive picture of healthy corn and a pretty girl when next they needed one. And finally, the third cover that cracked me up depicted a lovely blond woman in a shirtwaist and apron standing in a motel kitchenette, gazing out the window. The cover story purported to show how all the latest kitchen appliances could be fitted into a tiny space, but the look on the woman’s face clearly said, “I do NOT want to have to do ANY kitchen chores while I’m on my vacation!”

texasmonthly.com: You mention names and themes of motels in your story. Did you find any motel themes that were prevalent in Texas? If so, what were they?

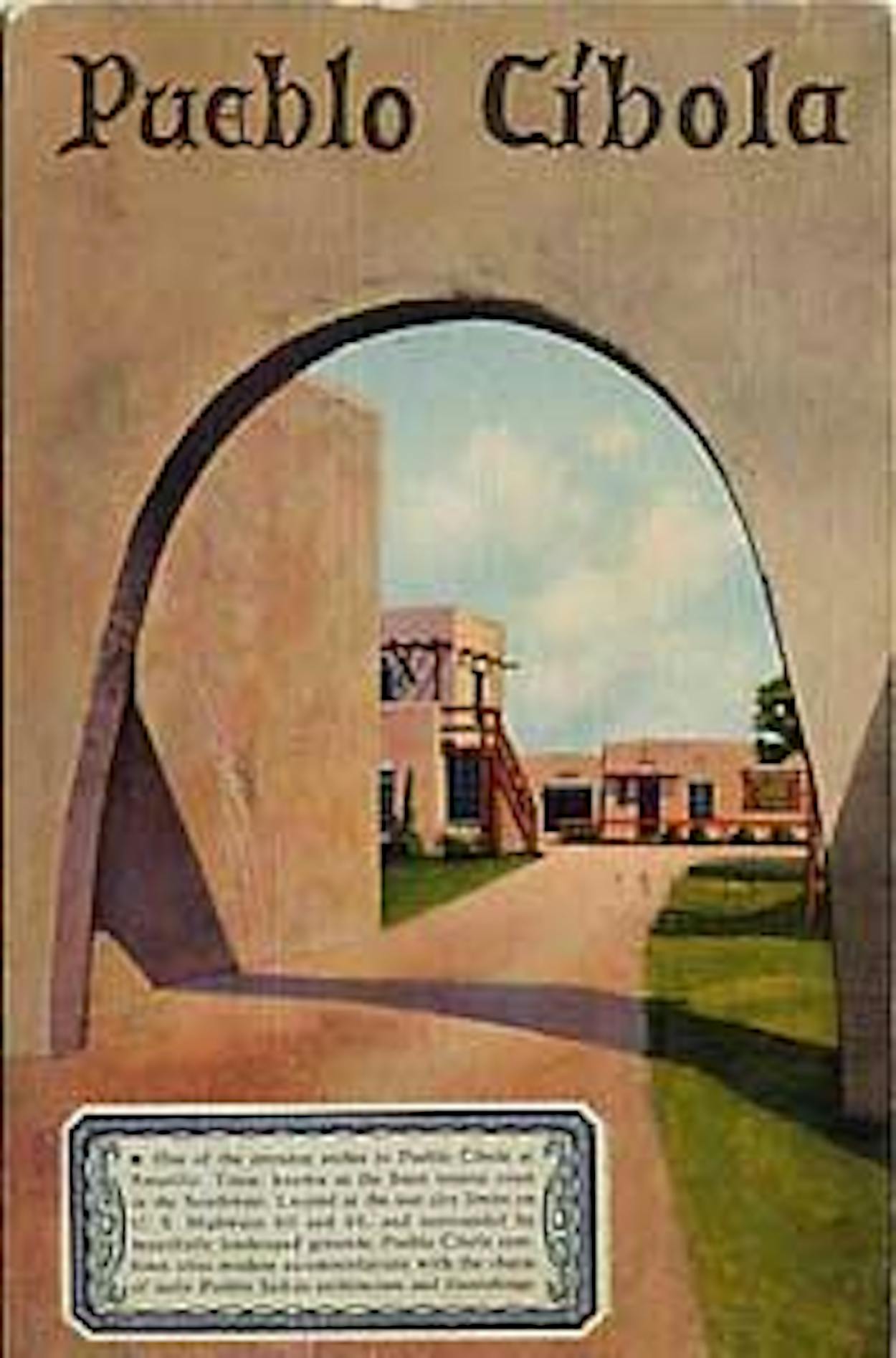

AD: This will come as no surprise: Cowboy motifs were definitely the most popular motel theme in the state—even in East Texas, which is far more Southern than Western. (In fact, cowboy themes were big all over the U.S.) Names like the Westerner, the Texan, the Sunset, and the Stallion were everywhere (there are even a few still around today). And naturally the design of these motels often included log fences, wagon wheels, a cactus, and the like. I once stayed in Wharton’s Tee Pee Motel, where the hand towels and pillowcases were embroidered with scenes of ponies and headdresses. That was in the late seventies; by the mid-nineties, it was the last tepee motel in the state, and the aging concrete structures, though still intact, have fallen into disrepair and haven’t been used in more than fifteen years. Another wildly popular motel theme was Mexican, and the favorite name, manos-down, had to be El Rancho. (The meaning was certainly clear, even to the monolingual.) South-of-the-border motels inevitably had signs adorned with some combination of a red and yellow sombrero, a sleeping peasant, and a saguaro cactus.

Other motels had themes that were unabashedly gimmicky, and certainly the novelty drew tourists; today postcards from these wacky motels draw sizable sums on auction sites like eBay. For example, a thirties-era tourist court in Amarillo called the English Motel featured separate little Tudor-style cabins, with steeply pitched roofs and arched doorways (plus authentic neon!). In Somerville, the Motel 36 converted eleven old railroad boxcars into two rooms apiece. Sometimes a motel picked one theme, and then moved on to another that was trendier, producing an amusing sort of cultural collision. In the early sixties, Chinese motifs were popular in fashion and furniture, so the Frontier Motel in McAllen opted to call its new restaurant the Bamboo Room. (The “Hop Sing Room” would have made more sense.)

texasmonthly.com: What was the most interesting thing you learned while working on this story?

AD: That motel guests used to have to pay for TV! They had to feed a quarter in for each fifteen minutes or so of airtime. That astonished me, simply because today a television is as essential to a motel room as a bed is. But in the mid- to late fifties, TV was still an unknown quantity, and motel owners weren’t about to pony up several hundred dollars per room for something that might prove to be a passing fancy. Runner-up shocker: Some motels expected guests to check out as early as nine o’clock in the morning.

texasmonthly.com: But eventually technical innovations such as television did lure customers. What other, if any, amenities did tourist courts tout to attract trade?

AD: Air conditioning was ahead of even television as a number one hook. Most families took vacations in the summer, of course, and the heat was the major reason a lot of people—say, Easterners—avoided visiting places such as the Alamo or the Grand Canyon, because the temperatures in the Southwest could be so oppressive. Air conditioning changed that. Because many travelers made what the motel biz used to call a through the windshield decision about where to stay, owners hyped “refrigerated air” and such on their highway billboards and neon signs out front. Eventually, everyone settled on the common term air conditioning. And by the early sixties—largely for the same reasons—you had to have a swimming pool. The water kept you cool outside—and I suspect the thought of shapely girls in swimsuits might have had an effect on a businessman or two. Ice machines were also de rigueur, although they were very expensive for little ten- or twelve-unit places run by an overworked couple, and a common complaint recorded in the pages of Tourist Court Journal was guests loading up thermoses or ice chests instead of merely the ice bucket in the room. That mountain of clear, glistening cubes was just too hard to resist.

Other amenities offered by motels in different parts of the state were amazingly varied. In El Paso, the Caballero Motel noted it was “Fifteen Minutes to Old Mexico.” In Childress, in the windy Panhandle, the Western Motel included on its postcards the reassuring phrase “storm cellar.” For winter travelers, a Snyder inn hyped “panel ray heat,” which sounded very space-age. Family-friendly operations might tout a merry-go-round or a sandbox, while lodgings near downtown aimed at the business trade might push steak specials in the cafe and free shoe shines. In one issue of TCJ, the editors asked subscribers what special services they offered tired travelers. One woman replied that she helped young mothers rinse out, wash, and hang up cloth diapers. Please, a moment of silence for that sainted motelier.

texasmonthly.com: When did the big chains take over from the homey independents?

AD: There were a few chains very early on. For example, Alamo Plaza Hotel Courts was a chain that started in 1929 in Waco. (They used the term hotel courts, but really it was a motel, since none of its buildings was ever more than two stories high and its guests parked right in front of their rooms.) The founders capitalized on the reverence that Texans and other Americans felt for the Alamo, and built their two-story motels with a curved roofline and similar architectural touches. Eventually they had 22 motels in six states. But the truly national chains—Holiday Inn, Best Western, and other household-name biggies—really took off in the fifties and sixties. This paralleled the post-war surge of industry and prosperity, and it also, alas, spelled doom for many family-run inns. Corporate motels could easily outspend mom-and-pop motels—they didn’t have to worry that much about guests pocketing the ashtrays or turning the AC down to 65 degrees. And since independents were iffy—some were spic-and-span lodgings, others were hot-pillow joints—name chains pushed hard to sell travelers on their accommodations’ reliability and uniformity.

Some well-known chains started in Texas, such as the Spanish-colonial-style La Quinta, which built its first giant motel in 1968 in San Antonio, to capitalize on the tourism generated by HemisFair. Other chains ended up here, like the inexpensive-but-friendly Motel 6, well remembered for the nineties commercial line: “We’ll leave the light on for you.” That company started in California in 1962 but moved to Dallas in 1988. It was named, by the way, for the original cost of a room—six bucks.

texasmonthly.com: Is there anything you would like to add?

AD: Yes. In the fifties and sixties, many motels ordered chenille bedspreads that were custom-woven with their name and logo. For example, a motel called the Route 66 Motel might show the famous shield-shaped road sign tufted in orange on white cotton, or one dubbed the Lariat might emblazon its name along with a picture of a twirling lasso in yellow on blue. Gee, I wish I’d thought, way back when, to take—I mean, purchase—one of those spreads! So few have survived, and they’re just wonderfully colorful and nostalgia-inducing. Oh, well. I do have my childhood collection of mini-soaps—baby-size bars of Lux, Palmolive, Ivory, and more. They’re still here, even if the motels where I snagged them as souvenirs are long, long gone.