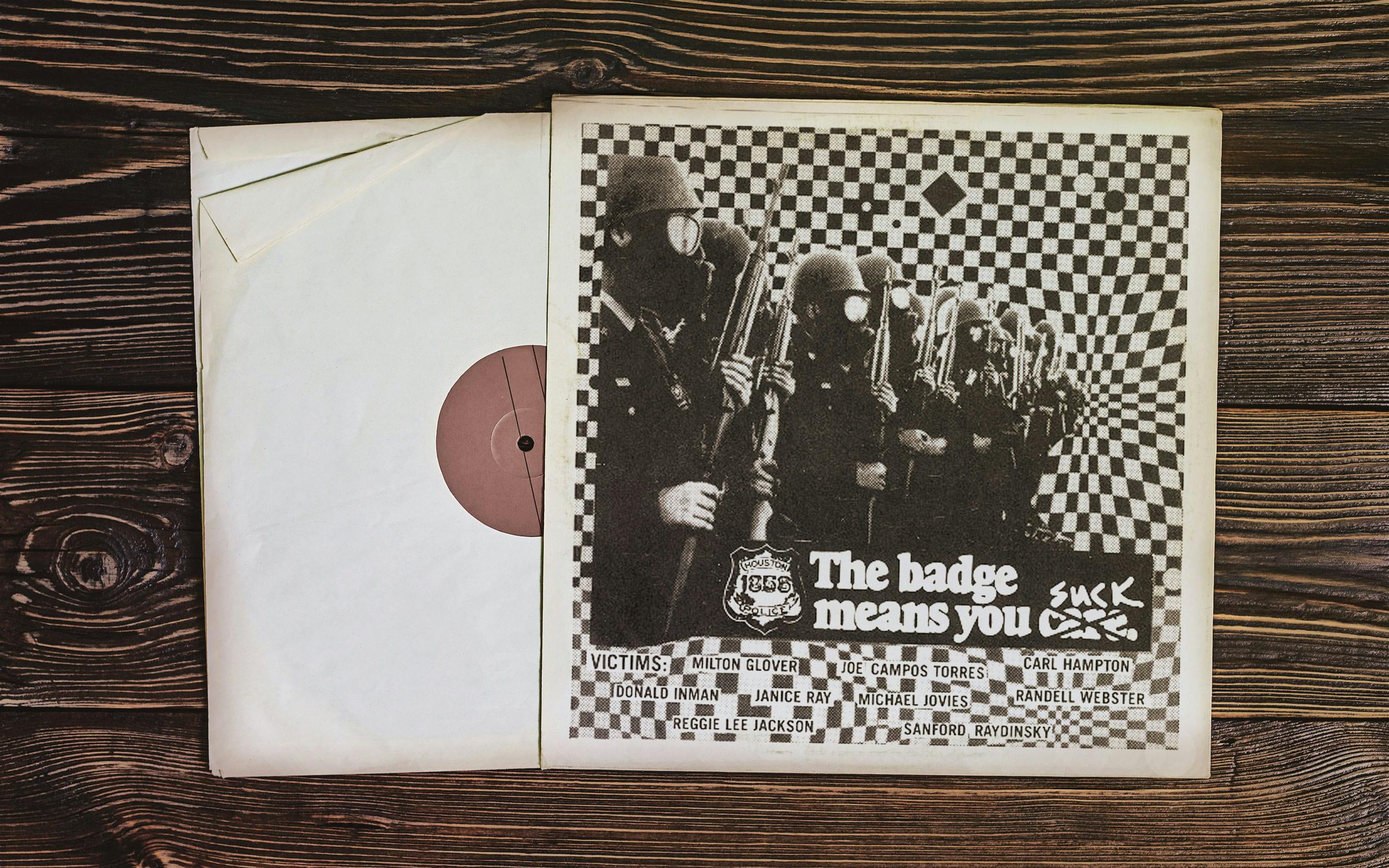

The reporters gathered in Houston police chief B.K. Johnson’s office were ready for a routine press availability on a Friday in 1981. But that day, instead of just taking questions, the chief had something he wanted to talk about: “The Badge Means You Suck,” a single by a Houston punk band called AK-47. Its title was a jab at the department’s “The Badge Means You Care” slogan, and its subject was a series of controversial killings of Houstonians at the hands of police officers. The song had been out for months, but Johnson had only just heard about it. Which was odd, because the lyricist and singer, known pseudonymously as Tim Phlegm, was local radio journalist Tim Fleck, who was present among the reporters as Johnson held forth in his office.

Fleck’s friend and former journalist Burke Watson remembers the moment well. The chief was livid, he recalls. “Just out of the blue, Johnson brought up this song, and obviously he was just, really, in high dudgeon about it,” Watson says. As he remembers it, the chief complained at length about how disrespectful the lyrics were. “He didn’t realize the lead singer was sitting right there in the office, a few feet from him.”

At the time, the Houston Police Department was notorious nationwide for the high number of incidents in which officers were accused of using excessive force. At least 24 cases of civilians shot by Houston police under suspicious circumstances were brought before grand juries in the three years before the 1977 death of Vietnam veteran José Campos Torres, a 23-year-old Mexican American who drowned after police beat him and threw him into a bayou. Torres is prominently featured in the lyrics of “The Badge,” along with Milton Glover, who was killed when officers said they thought the Bible in his hand was a gun, and Carl Hampton, a young Black Panther who was fatally shot during a standoff. (A 1977 Texas Monthly story by Tom Curtis detailed some of these cases, as does the new podcast Chicano Squad.)

“The Badge” is now part of the significant Texas contribution to the canon of songs critical of excessive violence by police, alongside the Bobby Fuller Four’s famous cover of “I Fought the Law” and Chamillionaire’s “Ridin’.” But only “The Badge” was written by a crime reporter who had played chess with cops to kill time while working the overnight police beat, and who turned his professional knowledge of the department into a critique of its tolerance of excessive violence and racism among some of its officers. The lyrics list Torres, Hampton, and Glover by name:

The men who killed Joe Torres

Never went to jail

The sniper who picked off Carl Hampton

Never paid any bail

The killers of Milton Glover

They might be pulling you over tonight

And if you happen to get shot

Well, I guess you started the fight

The specificity of the song and the sleeve of the seven-inch vinyl release, which lists four more victims, are echoed in the way activists today recite victims’ names at protests. The anger and empathy in “The Badge” have made it a cult classic in Texas punk circles, and it resurfaced on social media as an anthem against killer cops after George Floyd‘s death. Despite the intervening decades, the song continues to resonate as if it were written last summer. And forty years later, the band still has something to say.

Fleck had started his journalism career in 1971 covering crime for the Houston Chronicle; he would later work in news radio, and go on to a storied stint as a politics reporter at the Houston Press alt-weekly before returning to the Chronicle to serve on its editorial board. But in 1979, when he wrote the lyrics to “The Badge,” he was underemployed, not on staff anywhere, and living with roommates in Montrose. Politically, he knew where he stood, and it was with the victims of racist policing, just like his future bandmates. “It was an issue for us, it was a cause, and that’s where the song came from, was that anger. It was for real,” he says. “And it seemed like almost all the police shootings involved African Americans.” When he wrote the song, he wasn’t in a band and didn’t play an instrument, but he did like to listen to the Pretenders and Patti Smith.

He had that in common with Harry Leverette, who’d moved from Louisiana to attend grad school at the University of Houston and decided to start a punk band after being inspired by a Smith show at Cullen Auditorium. “I felt that I had been called to be part of a revolution and could not refuse,” Leverette says. He’d already thought of a name as provocative as his intentions: “The Kalashnikov AK-47 is the instrument of revolutionaries the world over.”

Leverette got his friend Jim Craine (later a founding member of Culturcide) to play bass, found a guy named Sleepy playing drums in a vacant lot on Westheimer, and persuaded a guitarist he used to play with at Louisiana State University, Stewart Cannon, to move to Houston to be in the band. Fleck showed Leverette and Cannon his song, and they brought him on to sing.

The first AK-47 show was a Rock Against Racism benefit in April of 1979, at Paradise Island, a Houston punk club. The band frequently shared bills with Houston punk legends Really Red (whose own anthem, “Teaching You the Fear,” chronicles some of the same incidents as “The Badge”) and the all-female Mydolls. Within the scene, AK-47’s members were somewhat affectionately ribbed as being hippies, because they declined to cut their hair and had noodly, bluesy guitar solos in their songs.

But Houston’s niche music scenes have never been overly concerned with strict genre conventions, and the band quickly gained a following, aided by “The Badge.” Longer than the average punk song, with a nearly minute-long guitar solo, the song has a pogo-suitable beat, a great riff, and an unimpeachable vocal sneer from Fleck.

The group released “The Badge” as its first and only single in March 1980. For months, the only waves the song made were among loyal fans. Then, Cannon says, Leverette made a unilateral decision to get some more attention. He posted fliers around town advertising the single, and one caught the attention of local TV station KHOU.

The station aired a segment on the song. “That’s when everything hit the fan,” Cannon says. As he remembers it, the piece ended with an anchor transitioning to sportscaster (and future Texas lieutenant governor) Dan Patrick, who “showed his disdain and mockery for us.” Patrick’s office didn’t respond to a request for comment, and the clip has been lost to history—it was likely ruined by flood damage after Hurricane Harvey, according to a station employee.

Spurred on by the publicity, the Houston Police Officers Association (now the officers’ union) filed a libel lawsuit against the band in April 1981. The suit claimed that “The Badge” exposed Houston officers, a group that included both those involved in the named cases and the majority who had not been, to “public hatred, contempt, [and] ridicule.” The musicians are named as defendants with the same pseudonyms they listed on the seven-inch insert: Cannon, James Allstar, Neutron Stu, Raton Pi, Sleepy, Tim Phlegm, and, for good measure, Mikhail Kalashnikov, the inventor of the AK-47, whom the band had facetiously named as its post office box contact on the record sleeve. By this time, Fleck was covering HPD for the Metro News radio service, reporting on the same department he eviscerated onstage.

No one was ever served in the lawsuit. D. Reid Walker, the attorney for the HPOA, told the Houston Post in 1981 that he’d been unable to track down any of the defendants. Today Walker says he has no memory of the case, which was officially discharged in 1985. A spokesperson for the Houston Police Officers’ Union said in response to a request for comment that the organization had nothing from that far back, and HPD referred Texas Monthly back to the union.

The lyricist’s identity remained an open secret within Houston’s journalism community. “[HPD] could never figure out who we were, and everybody in journalism knew and nobody told them,” Fleck says. “I really appreciated that.” A story about a punk band getting sued for libel of the cops was one thing, and merited only brief mentions in the Houston Chronicle and Post. A story about a police reporter being named in that libel suit would have been a very different matter, yet no one wrote it.

Still, the lawsuit caused more stress than Fleck, and a couple other band members, had signed up for. Alarmed by the headlines in the Houston Chronicle and the Post, at the next band meeting Fleck, Sleepy, and Craine said they wanted to quit.

Cannon and Leverette stayed on, however. After Fleck left, Leverette’s wife, Penny Smith, took over vocal duties, and he says the band found its peak with her as singer, Mike Huard on bass, and Carshal Heinbuch on drums. AK-47 continued to play shows until 1986, but never released another record.

While AK-47 didn’t generate the recorded output of other Texas punk legends, “The Badge Means You Suck” was enough to ensure an enthusiastic audience on the rare occasions the group has performed over the last 35 years. That includes three reunion shows—in 2009, 2012, and 2019—with Cannon and Leverette at the core, Huard on bass and his son Marc on guitar, and Michael O’Donnell on drums. Fleck didn’t participate in any of these, having never written another song or joined another band. In 2019, the men recorded a new protest song: “Trumpelstiltskin,” which pokes fun at the former president through the fairy tale of Rumpelstiltskin.

The group was getting ready to release the song when the May 2020 killing of longtime Houston resident George Floyd by a Minneapolis police officer sparked the nation’s largest and most sustained protests against police brutality in years. Links to YouTube rips of “The Badge” started cropping up on social media, and it was included in lists of songs about police brutality. The punk merch brand Dinner sold bootleg T-shirts, with proceeds going to a police reform nonprofit.

As the single gained in cult status, the recording remained a rarity. “The Badge” had stayed in occasional hard copy circulation via a bootleg compilation, but it wasn’t available digitally for purchase, and if you come across one of the originals, expect it to set you back $400 at least. Cannon and Leverette nearly put the song up on Bandcamp in the summer of 2016, but changed their plans when five police officers were shot and killed in downtown Dallas that July. Things felt different in 2020, and they posted it on Bandcamp at the same time “Trumpelstiltskin” was released.

In recognition of the protests against the kind of systemic brutalities that AK-47 called out, the group is donating all proceeds from both tracks to the NAACP Legal Defense Fund. Both men have health concerns that have kept them homebound throughout the pandemic and kept the possibility of future AK-47 recordings or shows up in the air. There’s still some unreleased material from the eighties that could see the light of day, however.

While Leverette feels struck by the “breadth and depth of public outcry” in 2020 versus 1980, Cannon says there’s a promise of change that hasn’t fully materialized yet—thanks in part to the institutions like the one that sued them forty years ago. “The police unions are protecting these bastards, and it’s time for that to stop,” he says. “It’s over time for that to stop.”

- More About:

- Music

- Police Violence

- Houston