Quarterback Caden Cooley stepped up to the line and surveyed the defense spread out before him. First, the freckled teenager looked at the safeties to determine if the middle of the field was open or closed.

“Open,” the fourteen-year-old said before checking the eyes of the defensive backs to his right and left to figure out whether they’re playing man-to-man or zone defense. After confirming he was seeing man-to-man coverage, he took the snap and did a three-step drop, surveying the field with the football clutched to his chest. When a slot receiver to his right cut in front of the safety and darted to the middle of the field, Cooley saw the movement just in time to release the football, securing a first down.

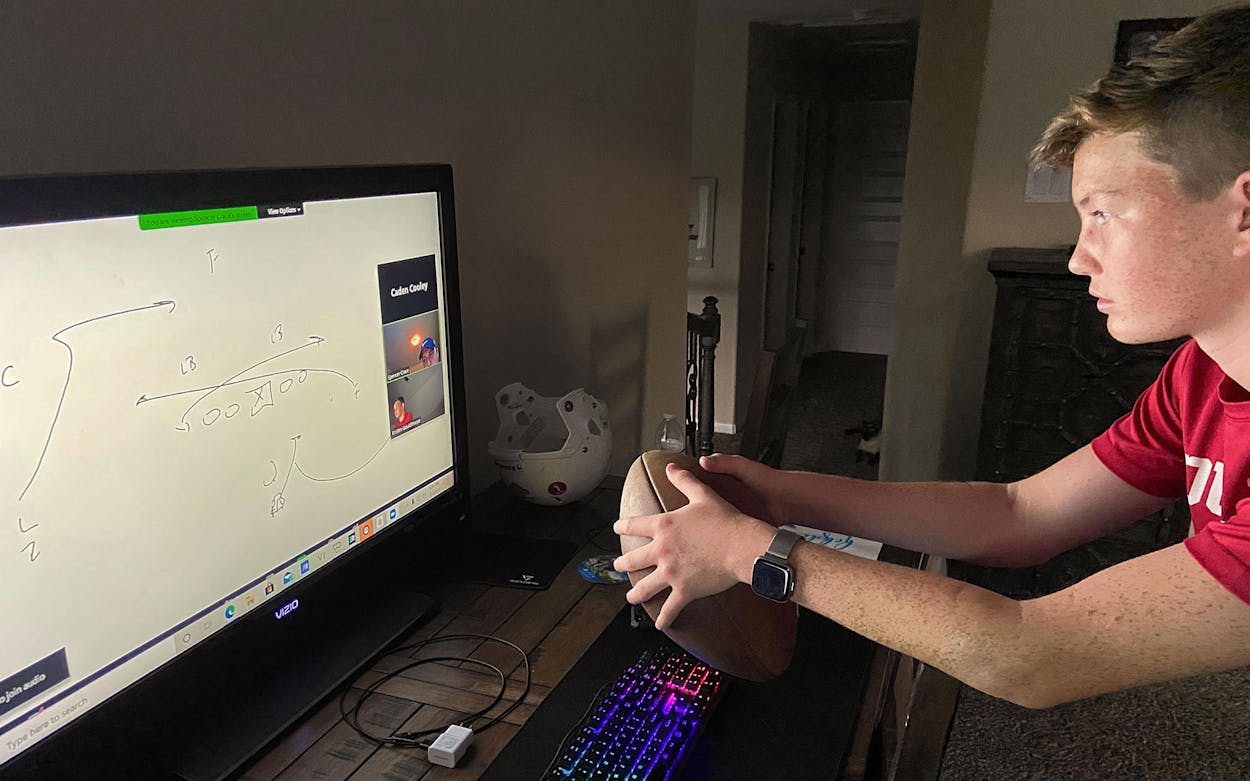

And yet, Cooley never actually threw the football, much less stepped on a real-life field. The entire sequence played out inside a virtual reality system called REPS, which was designed to give quarterbacks practice repetitions. The system costs between $3,500 and $4,500, according to the company REPS VR.

Given the choice, Cooley would prefer to train in the real world instead of the game room next to his Xbox controllers and his little sister’s crafting supplies. Unfortunately, in towns across football-loving Texas, as well as much of the nation in recent months, the pandemic eliminated the vast majority of in-person practices, making it risky for groups of players to train together.

The quest to become a starting quarterback and earn a college scholarship was already hard enough, requiring years of training with expensive private coaches, access to quarterback camps, seven-on-seven tournaments, all of it packed into a fleeting window of opportunity. This year, for players like Cooley, who have had to invent new ways to train and remain competitive, it’s even harder. The season officially started for most schools last week and now much of that hard work is being put to use.

“Not knowing what the end of the week or next week is going to be like has been the toughest on everybody,” said Bill Webb, the owner of QB Ranch, a private quarterback training outfit that works with nearly a thousand kids each year. “We have tried to do as much as we can to never cancel a session. We have tried to provide that stability because that’s what these kids are suffering from.”

Since her son began playing Pee Wee football, Kristen Gouldthorpe has invested thousands into his dream of becoming a starting quarterback. She came up with the idea of purchasing a virtual training system when she noticed how quickly her son’s brain reacted to video games like Fortnite. After doing some online research, she discovered that REPS VR’s designers claimed that their product produces the same sort of quick reactions. Summer football camps were canceled and her son needs to stand out at Cinco Ranch High School in Katy, where he’s facing off against six other prospective quarterbacks in his freshman class this season. The teenager is already working with private throwing and footwork coaches that charge up to $130 an hour.

“All of the kids that want to be competitive are doing that, too,” Gouldthorpe noted. “They are putting a lot of money into it.”

Behren Morton, a senior at the 3A Eastland High School, located between Fort Worth and Abilene, has never had a private quarterback coach. Because he plays at a smaller school with less exposure, the four-star rated player, who has committed to Texas Tech, has felt like he’s at a disadvantage. But this summer, with coronavirus outbreaks ravaging population centers, being in a far-flung town offered an edge. Even when team workouts were shut down for a few weeks, he had no issues getting teammates together to practice.

“Nothing really was different at all,” said Morton, who is already multiple games into his season because smaller schools were able to begin playing earlier. “I even had some camps throughout the summer.”

Two-time state championship–winning quarterback Dematrius Davis leads Galena Park’s North Shore Mustangs, a 6A school in Harris County. When spring football practices were canceled, he knew that he wasn’t going to get enough time with his receivers, so he started organizing practices with his dad and some teammates.

“My dad was doing social media, I was doing a lot of texting and group chats,” Davis said. “It really helped with losing the spring practice. Coming into fall camp, it really showed.”

North Shore head coach Jon Kay wasn’t even aware that Davis was organizing ad hoc practice sessions until he noticed evidence of the gatherings on Twitter. They even played some seven-on-seven games against other local schools with Davis’s dad and other adults serving as referees. The practices were so big and orderly that rival coaches became suspicious.

“I had coaches calling me asking why we were having full practices, which we weren’t even involved with, because it was so organized,” Kay said with admiration. “He was taking the same format that we would have been doing during spring ball and running it on his own with some other senior leaders.”

Early in the summer, Harlan High School quarterback Kannon Williams couldn’t work with his quarterback coach or get his friends together in San Antonio because of COVID-19. The 2020 season is a vital one for the senior who hasn’t yet committed to a college team. So he turned to a trusted throwing partner he’s known all his life—his mother, Rebecca Rogers.

“I broke her finger when I was in sixth grade so we stopped doing that for a while, but at the height of COVID it came back,” Williams said. She bought receiver gloves to help with the impact, but Williams also made sure to dial back the speed a bit. “I definitely don’t blow my mom up.”

The throws were important for Williams. Though he has a quarterback coach, he was only able to do virtual training sessions with him.

For all the players turning to expensive coaches and virtual training systems during the pandemic, others, like Eddie Lee Marburger, embraced an entirely different approach. To keep himself sharp, Marburger, a senior quarterback at Sharyland Pioneer High School in Mission, turned to a tried-and-true training method that has worked for quarterbacks for generations: a rubber tire hanging from a rusty soccer goal.

As COVID-19 devastated the Rio Grande Valley, Marburger, rated a three-star prospect by Rivals.com and committed to the University of Texas at San Antonio, had trouble getting his teammates on a practice field. Undeterred, he has been doing drills with his dad. Sharyland Pioneer head coach Tom Lee, has been impressed.

“He’s worked extremely hard during the coronavirus,” Lee said.“ I probably don’t have one single kid in my program that’s worked as hard as he has during this time.”

With a Division I FBS scholarship already in the bag, he doesn’t actually have to play this season. South Texas schools didn’t even begin practices until September 28, three full weeks after the rest of the state’s 5A and 6A schools began their practices. In fact, he could see some benefits in a potentially canceled season.

“Without having a full season that means you get to work extra and be working out and getting yourself ready for the next level,” Marburger says.

He’s been so driven to improve this offseason because of how last season ended. Despite being the superstar quarterback responsible for much of Sharyland Pioneer’s success, he blames himself for their Class 5A Division II regional semifinal loss in 2019.

“That gave me so much fuel because I’m the reason we lost the game,” Marburger said. For that to be in the back of your mind every day, it gives you the energy to work out ten times harder.”

- More About:

- Sports

- High School Football