(Editor’s Note: Updated Below)

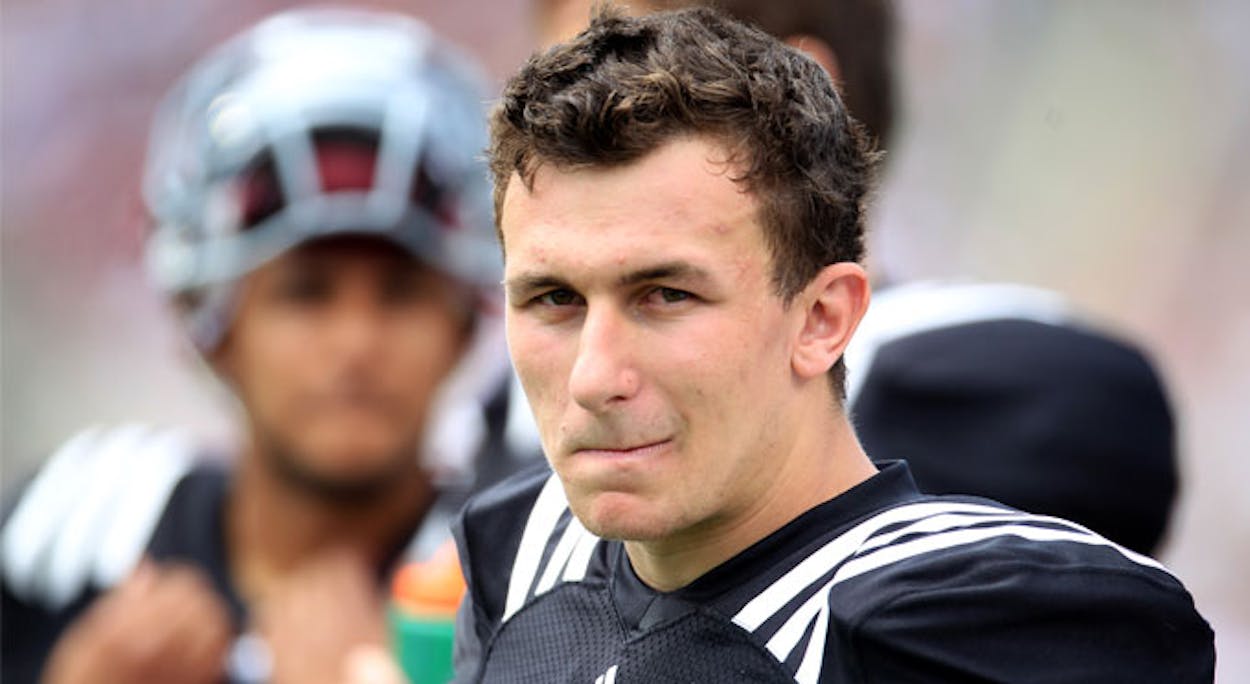

One of the more amazing aspects of Johnny Manziel’s electrifying run to the Heisman Trophy last fall was that he came within a hair’s breadth of not playing football at all. In recent lengthy interviews for an upcoming Texas Monthly feature, Johnny and his parents told a story that began in the early morning hours at a College Station jail and ended with a dramatic ruling in a Texas A&M dean’s office on August 14.

As is now well known, on June 29, 2012, Manziel was arrested for fighting. As eyewitnesses told the story, around 2 a.m., a friend of Manziel’s, who was drunk, said something that was taken by an African-American man as a racial slur. Manziel, trying to make peace, had stepped between the two, saying that his friend had not meant to use the words and that he was taking him home. The older man had then pushed him, Manziel had pushed back, and the two had begun throwing punches.

That was when the police arrived. Manziel was booked for disorderly conduct, failing to properly identify himself, and for carrying phony driver’s licenses.

At the time, Manziel had been fighting a losing battle for the job of starting quarterback. The arrest hurt his chances even more. Knowing this, his family hired a lawyer to defer his court case while he fought for the starting position.

When fall camp started in College Station on August 4, Manziel, who had worked hard all summer to rehabilitate himself, performed well, impressing his coaches with his passing and running. He was beginning to hope that he might have a shot at starting after all.

But details of a story that has only now gone public show how close that came to not happening. As was reported yesterday by Kate Hairopolous of the Dallas Morning News, and as the Manziel family explained to Texas Monthly, A&M suspended Manziel over the summer, in the weeks following his arrest.

According to Manziel, he learned of the suspension in the middle of two-a-days in early August 2012. The punishment would last throughout the upcoming semester, meaning he would be unable to play football. A&M has its own internal system for dealing with students who have gotten in trouble.

“When you get in trouble, a school disciplinary board reprimands you,” Manziel said. “They pretty much prosecuted me off the story in the Bryan newspaper.They banned me from athletics and from my scholarships. I had worked hard, and done everything Coach [Kevin] Sumlin asked me to do, and then they told me I couldn’t play anymore.”

Alan Cannon, A&M’s sports information director, referred questions to a university spokesperson who was unavailable for comment. He did say that such questions were a university matter, not a sports department matter, and that issues of personal privacy were involved.

According to Manziel and his parents, the ban took effect immediately.

“We were shocked,” Manziel’s mother, Michelle, told Texas Monthly. The family had not expected the punishment to be so severe, and began to consider alternatives. “If they’re going to do that,” Michelle said, “we’re fixing to have to transfer him to a junior college to get him to play.”

But before that happened, Manziel, with the help of A&M sports officials, mounted an appeal to A&M’s Dean of Student Life. “For about seven days, until I got my appeal in,” says Johnny, “I was not allowed to compete in any athletics.” This was in the middle of fall camp, critical days that would determine who the starting quarterback was. *

Manziel completed his appeal, which included letters of support from Sumlin and offensive coordinator Kliff Kingsbury, and then, he said, “I met with them. They ruled after a long decision process.”

On August 14, the Dean of Student Life—in a decision that would have astounding consequences for A&M’s football season, to say the least—reduced Manziel’s punishment from suspension to probation, which meant that he could play football. A mere day later, on August 15, to the surprise of Aggies everywhere, Sumlin announced that Manziel would be his starting quarterback.

And the rest, as they say, is history.

*CORRECTION*

The original version of this story quoted Johnny Manziel as saying he missed “about seven days” of Texas A&M football camp in August of 2012. While the quote itself was accurate, its meaning and context was presented incorrectly.

The update below offers a fuller accounting of the Manziels’ recollection of the timeline, while the university’s student conduct policies are further explained in a separate post. TEXAS MONTHLY regrets the error.

According to Johnny and his parents, on August 6, two days after Fall Camp had started for the Texas A&M football team, Johnny Manziel appeared before a 3-person panel which reviewed his case, interviewed him, then decided that he would be given a university sanction known as “Conduct Probation.” This meant that Johnny could not represent the school for a semester, which meant that he could not play sports. It meant that he would miss the entire football season.

“After the meeting of the panel, Johnny called me and said, ‘Mom, you are not going to believe this,'” says his mother Michelle. “‘I got Conduct Probation. I can’t play. I can’t play at all.’ We thought: This is crazy.”

Johnny then had seven days to make an appeal to Dr. Anne Reber, the Dean of Student Life. He was allowed to practice during that time; as the A&M student rules explain, “decisions made by a lower level hearing body shall not be final until an appeal deadline is passed, or when the appeal process is exhausted, or when a student chooses not to appeal.”

But he knew that if the panel’s decision was upheld, he could not play football.

According to the Manziels, on August 8, a meeting was held with football coaches, Johnny’s parents, and Johnny, among others, to help prepare the written appeal. Coaches wrote supporting letters.

“We were all in this together,” says Michelle. “It was a total team effort.” She adds that neither she nor her husband Paul nor Johnny seriously considered transferring to another college during this time (that only would have happened had Manziel lost the appeal).

On August 10, Johnny submitted his appeal. Four days later, the ruling came: Johnny would receive a lesser sanction that would allow him to play football, but did require him to take a 6-hour class.

- More About:

- Sports

- College Football

- Aggies

- Johnny Manziel

- Johnny Football