It’s a heavy muzzle of a summer night, in a sawmill town in the Piney Woods. This is years and years ago, before air-conditioning, and people sit on porches, coated in sweat and resin and sawdust. They fan themselves and listen to the katydids’ drone. Then out of that hot stillness comes a voice, speaking or maybe singing, or speaking in a lilt that has a music to it. A person—a woman, let’s say—has something to tell.

Inside one house, there is a boy who’s supposed to be sleeping by now, a slender, dreamy, nervous boy, the son of a mill worker and a melancholy young mother. He lies on a pallet, not yet asleep but not quite awake either, as voices from the porch wash over him. What are they saying? What prods them to say it? One day he’ll write about “those dreaming, shy, solitary, and secret-ridden beginnings in a back-town of Texas,” in stories and novels that repeatedly dramatize the act of storytelling itself.

William Goyen was born a hundred years ago in the small town of Trinity, in East Texas, and the country people of his youth kept speaking to him long after he left the country. The stories he’d heard became the condition of the books he went on to write, the underpinning of his fiction, so that even when he wasn’t writing about East Texas, he tried to listen to his stories and novels as he composed them. “I have to be freed to let somebody tell me what I’m telling,” he once said in an interview. “It’s often a woman’s voice talking to me.” What he took from the world of his childhood was nothing so simple as a supply of regional lore or a knack for replicating dialect. His work vibrates with longing and agitation, as he wrestles with the very impulse that drove him to write: What are these stories we tell and how do they make us the people we are?

He died in 1983, and his books are scarcely known today, yet in them he transformed the language of his childhood into a singular instrument: a prose style all his own. He could be brilliant on one page and overripe on the next, always pushing his art to the brink.

He composed much of his fiction in a register of fable or myth, and he shouldered his own personal myth, a highly romantic sense of himself as an artist—as “the totally isolated genius,” wrote British poet and critic Stephen Spender, who met Goyen in the forties. But there was another side to him, Spender recalled. “Goyen could be simple and straightforward, extremely funny and rather malicious. He was often all these things in conversation, when he was not on his high horse of being the loneliest artist in the world.”

Much as he might have come across as a lyrical writer racked by existential anguish—much as he actually was that—Goyen also had an absurdist sense of humor and a fascination with lust and sex that in combination produced some fairly outrageous storytelling. Those earthier impulses are evident in his early work but emerge full-blown in his 1974 novel, Come, the Restorer, a crazy fantasy of desire and corruption in the oil patch. This happens to be the first book by Goyen that I read, at a time when I was home with a new baby and ricocheting between the extreme states that new babies bring. It’s possible that in my raw exhaustion I was more receptive than I might’ve been otherwise, for there are sections of the novel that read like dreams you’d hesitate to tell anybody about, involving a comatose man with a magical erection, a tightrope walker shooting off in the woods, and, later on, passionate sex between the tightrope walker and a woman who doesn’t recognize him as her adopted son.

As a reader, I’m not generally drawn to that type of thing (if it even is a type—surreal erotica? Circus pastoral?). There’s enough semen in the novel to make a terrible double entendre of the title. Yet I was hooked by the voice, alternately puckish and plaintive and bawdy, recognizably Texan in its rhythms but strange to me. And not only that: it’s a wildly surprising book, the work of a seething talent who has thrown caution to the wind.

He nearly died before he was born. One day when his mother, Emma Goyen, was seventeen, recently married and pregnant with him, she and a friend went for a swim in the Trinity River. They somehow went under, and both girls had to be pulled out of the water by Emma’s husband, Charlie, and while Emma survived, her friend did not. No doubt the event cast a long shadow over Emma, and the story stayed with her son. He grew to be a sensitive, seizure-prone boy, who often had to look after his younger sister because, as he later recalled, his mother was sick and in bed much of the time. The drowning of a young bride would figure into his first and most critically successful novel, The House of Breath, published in 1950. And a few years after that book was published, he would write of his artistic process, “It is purity of mind one strives and wishes for—an area of purity and simplicity where one pulls up, as from a shore, out of the mud and the swamp some whole, clean shape—a rescue.”

His mother is at the center of another family story that worked its way into his fiction: every time the Goyens drove the seven miles from Trinity to the town of Riverside, where Emma’s sister lived, Emma would ask Charlie to stop the car before they reached a trestle bridge that spanned the Trinity River. Deeming it too rickety to cross by car, she would get out and walk, while her husband and children, having already driven ahead, would look back “at the small figure of our mother laboring darkly and utterly alone on the infernal contraption which was her torment.”

Goyen wrote that line in a short story called “Bridge of Music, River of Sand,” inspired by his own memories. The predicament of the mother on the bridge is striking and, as a literal matter, confusing. If she thought it was so perilous to cross the bridge by car, why would she let her children do it? The fictional mother who is “darkly and utterly alone” on the bridge seems of a piece with the actual mother who almost drowned and was often sick in bed—a woman with a mysterious burden that pulls her away from her family. Once safely across, the mother in the story announces: “I vow to the Lord that if my sister Sarah didn’t live in Riverside I’d never to my soul come near this place.” The line has a colloquial sound and a spiritual inflection, which is quintessential Goyen. Many of his characters seem to grapple with something that goes almost deeper than they can say, and he lets us hear them try to say it.

He had an early love for music, and after his father refused his requests for piano lessons, his mother cut a picture of a keyboard out of the newspaper and gave it to him. Pasted onto cardboard, it became his piano, which he played in secret. At night, in bed, he composed music, and he wrote stories as well.

There are passages in the books he later published that have a furtive feel to them, of something being whispered under the covers.

Goyen once wrote that he suffered from “homesickness that couldn’t be eased by going home.” His sense of exile seems to have been congenital, but it also came from early experience. By the twenties, the great stands of virgin pine that had brought lumber companies to East Texas had been hacked away, and many of the sawmills closed down. In 1922, the year Goyen turned seven, the family moved to Shreveport, Louisiana, and then to Houston, where his father found a job selling lumber. They lived in a small frame house in Woodland Heights, among neighbors who’d also migrated from the country, neighbors whom Goyen saw—and also heard—as burdened by loss. “This was the lament I heard from these gentle uprooted people,” he would recall, “in their singing speech, their poignant outcry (my mother’s joined them, often led them): ‘When we go back one day to Red River’; ‘When we all go home to Polk County.’ Or to Honey Grove, or to Lovelady, Tyler, Big Springs.”

Although Goyen, as an artistic and delicate boy, wouldn’t have been particularly well suited to life in a small East Texas town (and eventually he discovered theater in Houston, which he loved, and studied literature at Rice Institute), he identified with his mother and her chorus of displaced persons. The House of Breath draws directly on his memories of Trinity—the town he names Charity in the novel “is really Trinity, Texas, truly, accurately described,” he said—and the book’s tone calls to mind those emigrants who’d been his neighbors. The novel is an elegy for the place he left as a boy.

Uprooted again by the Second World War, he joined the Navy and left Texas. The estrangement he’d already felt in Houston could only have been compounded by life on the open sea, yet there, surrounded by nothing but water, Goyen found himself overwhelmed by “long continuous ‘movies’ of remembering,” as he wrote in a letter to a friend. He would later say that The House of Breath had originated with a vision he’d had one cold night as he stood on deck. “I just called out to my family as I stood there that night. . . . I saw this breath come from me and I thought—in that breath, in that call, is their existence, is their reality.”

He was thirty when he left the Navy, and he spent four more years working on the book, living for much of that time in a rustic cabin outside Taos, New Mexico, with a former shipmate, Walter Berns. They befriended Frieda Lawrence, D.H. Lawrence’s widow (whom Goyen would remember as “just a wonderful great big huge piece of a woman”), and also consorted with the heiress turned bohemian Mabel Dodge Luhan, a painter named Dorothy Brett, and visitors like Tennessee Williams and Spender. Goyen was as happy there as he ever was. His relationship with Berns was platonic, but he may well have slept with Spender, whose wife, Natasha, called Goyen “a man-eating orchid.”

The House of Breath, like all his longer fiction, is not a conventional novel with sustained plots and character arcs. He eschewed the cumbersome apparatus of the realist novel, all the stage directions and setups, the phone calls and cab rides. In this book and later works, Goyen would link disparate sections, each concerning a different character or episode, a process he likened to sewing together the medallions of a quilt. “A spangled fish” is how Reginald Gibbons, a poet and Goyen’s literary executor, aptly describes The House of Breath in an afterword written for the book’s fiftieth anniversary—it’s shimmering and elusive.

In the beginning of the novel, a first-person narrator, alone in some faraway place, starts to reconstruct the town of his youth, compulsively listing the things of that world. There are castor-bean leaves, muscadine vines, go-to-sleep flowers, sycamores, live oaks, bottomland palmettos, and “azure fungus flowers”; there are snap turtles, water moccasins, and bullfrogs; there are the Bijou Theatre and the City Hotel; and there are Aunty, Uncle Jimbob, Aunt Malley, Uncle Walter Warren, Christy, Follie, Sue Emma (a.k.a. “Swimma”), Berryben, Granny Ganchion, Jessy, Maidie, and Miss Hattie Clegg. As the scholar Clark Davis points out in an excellent new study of Goyen’s life and work, It Starts With Trouble: William Goyen and the Life of Writing, the narrator conjures what a young boy would’ve seen: a tree he used to climb, men at the sawmill urinating in the lumber stacks. The narrator also recognizes the town’s violence and racism. For all his wistfulness, Goyen remembered Trinity as a world of terror, where he twice saw a black person tarred and feathered.

Other speakers take turns narrating, some of whom are people in the town—a mother who goes blind waiting for her son’s return, a grandmother in a cellar who talks to a worm—but the Charity River and a voice from the bottom of a well also chime in. If the book’s atmosphere of poetic despair grows too thick at times, it’s punctured soon enough by plain speech. (Here’s the voice from the well talking about Swimma’s jockey husband: “That little ole banty come drivin up for her in a black sedan of some kind longer’n the Katy Locomotive and they went off ballin the jack in a cloud of black Charity dust.”)

Goyen strove for the impossible—to somehow write his way out of his own alienation. “We wished we could find one word, one strong word, small but hard as a stone, that would mean our aloneness in the world, and say it in great crying voice, hurling toward the moon,” his original narrator says. The characteristic movement of his books is from incantation and storytelling (the intimacy between teller and listener was one form of connection that Goyen cherished) to some sort of erotic experience (sex was another). The House of Breath, though tamer than Goyen’s later works, gives us a boy’s first experience of ejaculation, his spying on his naked uncle, and that uncle’s recounting of his own sexual history—this last in a scene of menacing tension.

The book was critically well received. Goyen’s family hated it. Pieces of the novel appeared in a magazine two years before the book was published, and after reading those, his mother wrote in a letter, “Am sorry to say am really disappointed in your work, and if that is the kind of literature you are going to write, I hope you never succeed (and you won’t).”

Emma went on like that, signed the letter “Love Mom,” and then wrote a postscript: “Now add this to one of your books, it will be wonderful that your Mother has lost hope in her Son.”

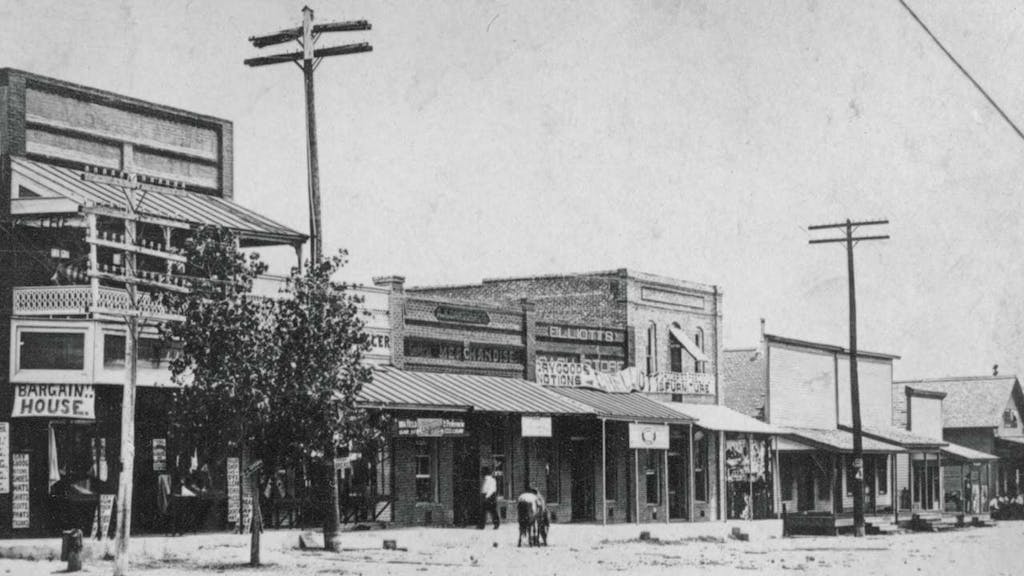

In July I went to East Texas, searching for traces of Goyen’s Charity in present-day Trinity. I did so pessimistically, not knowing what to look for. Muscadine vines? A bullfrog? The house Goyen was born in a century ago no longer stands, I’d learned. If anything I thought I might hear some echo of his people. At a gas station, I strained to eavesdrop on a man in overalls who was filling up a church van. All I caught was the word “probation.”

I talked to another man who mentioned a “rinky-dink railroad” that used to run through town, and the way he said those words—the hard consonants of “rinky-dink” striking like coins into a cup, the vowel sounds of “railroad” drawn out and more or less extruded from the front of the mouth—made me think for a moment that I was on to something, that maybe the whole tension in The House of Breath between the hard material of life and its lyrical undertow was actually embedded right in the accent! The tension between consonants and vowels! But that’s the sort of thought that pops into your head when you’ve been driving around East Texas by yourself in a rented Ford Focus, looking for more than you’re finding.

Trinity is dominated by Texas Highway 19, which hadn’t yet been built when Goyen lived there. Highway 19 runs from Huntsville to Paris and is now used to travel between Dallas and Houston, as an alternative to the interstate, and so the town sees more than its share of traffic. While I was there, cars streamed steadily past resale shops and auto-repair places and a McDonald’s—itself an indicator of the traffic, since Texas towns the size of Trinity (population 2,700) don’t typically attract that franchise. Inside the McDonald’s, more men in overalls sat silently drinking coffee as Fox News played on a TV that they may or may not have been watching.

I couldn’t get much of a fix on the town by poking around, and it was hard to avoid the thought that the kind of cultural specificity on display in The House of Breath doesn’t even exist anymore. I had with me Goyen’s Selected Letters From a Writer’s Life, which includes letters he sent to his German translator Ernst Curtius. Evidently Curtius had sent a lengthy list of questions about words and phrases from the novel he didn’t recognize, and Goyen went about defining them: cartons of Pet’s milk, mayhaw, holy rollers, croakersack, dirtdobber domes, Epworth league, blueing bottles, stock tub, prism curtains, kewpie doll, Lava soap, crapshooter, potlikker, homebrew, Chatauqua, goobers, hayrides, shotgun houses. The list goes on and on, evoking what seems like a fuller, more articulated world than is to be found in Trinity now.

But maybe it’s my own eye that has gone dull, along with the culture. I have no idea what a muscadine vine looks like.

I did go looking for the bridge to Riverside. In addition to putting his mother’s crossings directly into a short story, Goyen wrote elsewhere about aerial performers: a trapeze artist in his novel Half a Look of Cain, the tightrope walker in Come, the Restorer. That tightrope walker in particular seems to recreate something of the mother’s walk, while also serving as a metaphor for Goyen’s own writing. His books are themselves high-wire acts, born of a struggle that was also a performance.

I had some confusion, though, about whether any part of that bridge still exists. There are currently three bridges near the point where Highway 19 crosses the Trinity River: a plain, four-lane highway bridge; an older bridge just beside it, capped by silvery steel trusses and now dedicated to the Veterans of Foreign Wars (which is just about as much tribute to Goyen as one finds in Trinity County); and, a little farther away, on the other side of the highway, the oldest of the three, a rust-colored railroad bridge built in 1915. Because I thought this last bridge might be the one mentioned in “Bridge of Music, River of Sand,” I tried to get closer to it on foot. I cut through an RV park and was pointed toward the train tracks by a shirtless man lazing in a golf cart. I walked along the tracks, up to the edge of the bridge, and peered into the swampy area below. It was as though I were looking for the narrator of Goyen’s last novel, Arcadio, who tells his story while sitting under a railroad bridge—but here were only Bud Ice cans and Styrofoam cups and discarded boards scattered over blue river rock. A boat motored by, and wavelets lapped at the muddy banks.

I had somehow convinced myself that this was just a bridge from an old book, no longer used by trains. Reality tapped on my shoulder: I noticed the shininess of the rails, and I decided I’d better retreat to a safer distance. Before I left, though, I looked past the railroad bridge and saw a pair of concrete pillars rising out of the water, topless abutments that turned out to be all that remain of the trestle bridge where Goyen’s mother labored darkly and utterly alone.

Goyen, who was bisexual, had affairs with other artists and sometimes with older, more-established artists from whom he craved approval. One of those was likely Spender; another was fellow Texan Katherine Anne Porter. The brief, ardent relationship between two of the best literary stylists ever to come from Texas began with expressions of mutual respect. He first paid her a visit in 1947, assuming the role of literary disciple, and she commended The House of Breath in a review for the New York Times. They became lovers in 1951, while Goyen was in residency at Yaddo, an artists’ colony in upstate New York. He was 35; she was 60. By then they’d both spun their modest, small-town backgrounds into writing more lauded than read.

Porter had a habit of denouncing gay men and also falling for bisexual men, whom she would then monitor for signs of betrayal. Goyen later wrote a double-edged portrait of her, channeling Porter’s voice and making her out to be a kind of literary supremacist, who rambles drunkenly at a party, “Why honey women where I come from leaned over fences and spoke to each other in pure language of the Elizabethans and what these nasty writers do to our good English language, argot, filthy words; jews and homosexuals. And honey they won’t whip me, the nasty little clayeaters.”

In her biting short stories, Porter told of human treachery, while Goyen created singing narrators who longed for past loves. Over the course of their romance they followed their own scripts: he wrote her love letters (“I do brush against you like the cat again, waiting for your hand to come down through my fur”) but maintained his distance, fleeing to Houston and claiming he was too busy with his writing to come to New York to see her. She suspected him of falseness. The affair didn’t last long.

While Goyen’s fiction cried out for human connection, he was all too capable of using his writing to keep people away. Even so, he was rarely uncoupled, and he had significant, lengthy relationships with the painter Joseph Glasco and with the actress Doris Roberts. He first courted Roberts as a performer, asking her to appear in a play he’d written, and they married not long after, in 1963. He loved her “fanciful kind of life,” he said in an interview. “She’s made-up half the time, and I like that. . . . For an old East Texas boy, that’s pretty good, to get him a wife with full makeup. Wigs on a lot, lashes.” They stayed together until his death. (Roberts later became well-known for her film and television work, often playing somebody’s mother or mother-in-law, and won four Emmy awards for her role as Marie Barone on Everybody Loves Raymond. Now ninety, she maintains an active Twitter account, where she recently posted two pictures of herself with Goyen—“He was more than I ever dreamed of as a husband,” she tweeted in July.)

After The House of Breath was warmly received, Goyen went on to write five more novels and many short stories, yet he never found a wide audience. His introspective, fractured mode of composition might have been partly to blame, and as Davis notes, critics didn’t know where to place him: Was he a Southern writer? Certainly his material didn’t fit people’s preconceptions of Texas, nor did he want to be considered a regional writer at all, though he was adamantly a Texan (in absentia—he lived in New York for many years, and in Los Angeles toward the end of his life). Goyen’s books attracted distinguished translators in France and Germany, and his work may have been better known abroad than it was at home.

His second novel, Half a Look of Cain, was rejected by Random House, which had put out The House of Breath, and he never saw it printed during his lifetime. (Northwestern University Press published an edition in 1998.) This is my favorite of Goyen’s books. It coheres only loosely, but its nesting-doll narratives present a moving vision of human caregiving and healing. There’s a mix in all Goyen’s work of affliction and relief, sorrow and humor, not to mention sex and death and mystery and some downright bizarre behavior. In Half a Look of Cain, I think he got the balance just right.

One recurring figure in Goyen’s work is that of a mystical stranger who arrives in a small town; in this novel it’s Shipwreck Kelly, a man who appears in a town and perches on a flagpole for days, as the residents alternately revere him, suspect him of spying or worse, and try to persuade him to advertise local businesses. Shipwreck Kelly, up on his pole, shares something with Goyen’s circus performers, and of course with Goyen himself. The same images and episodes reappear in his books like totems, symbols he kept interrogating, unable to let them rest.

His struggle to write and the human struggles he wrote about took their toll on him, and in 1966 he took an office job, as an editor at McGraw-Hill. He all but stopped writing, which made matters worse, and he drank heavily. But Goyen, who depicted prophet figures and rescuers in his work, experienced two distinct conversions himself. The first one came in 1971, at an artists’ colony in Connecticut, where he had a religious vision, what he called “a dramatic and wild re-discovery of Jesus Christ.” This was an unconventional Jesus, whom Goyen saw as a lover—that is to say, he vividly imagined the two of them, Jesus Christ and Bill Goyen, having passionate sex somewhere in the vicinity of the Gulf of Mexico. Half-deranged as it sounds, it seems to have given him a new sense of purpose. He completed and published two books: Come, the Restorer and a short retelling of the life of Jesus. (That retelling did not include his explicit personal vision. He did submit a short version of his homoerotic Jesus encounter, conceived as a pamphlet, to a Christian publisher, which rejected it in no uncertain terms.)

Then, in 1976, he quit drinking and joined Alcoholics Anonymous, attending meetings regularly for the rest of his life. When he died of leukemia seven years later, he had just finished Arcadio, its title character a half-Mexican, half-Anglo hermaphrodite raised in a whorehouse, an erotic saint who speaks to the reader in a mix of Spanish and English. In this book, Goyen eludes me—I find the narrator’s mestizo voice problematic and a certain over-the-top episode just too far over-the-top—but he fully invested the character and the novel with his sexual torment, his feelings of exile, and his sense of the degradations people inflict upon one another, and once again he turned his obsessions into a peculiar, tender, echoing song.

The cover of my copy of The Collected Stories of William Goyen, which Doubleday published in 1975, consists simply of the title superimposed over a black and white photograph of Goyen, in the style of so many of that era’s author photographs, severe and compelling: here is a Serious Artist. Goyen wears a wrinkled white shirt, open at the collar, and stares back at the camera. He’s almost sixty. His body is lean and his gaze inscrutable, so that I’m not sure whether it’s sadness or wariness or weariness I see there. The photograph, along with that whole genre of photographs—the mid-century American novelists who are tucked among my shelves, looking intelligently out from their book jackets—evokes an era when the novelist was a more central figure in American culture, the novel more celebrated. It’s easy enough for a writer today to look back with nostalgia, but what that picture of Goyen calls to mind is the burden of his own aspirations. He wanted so much for his books. “I want to make literature that will speak for my time and out of my time and stand for all time,” he wrote in one letter. In another he described his artistic purpose as “to help us return ourselves to a way of feeling, a way of looking and responding to our own human experience.” I think of Goyen and his difficult toil with great admiration, because that’s one thing art ought to do, to help us see the world in a new light, yet I also think of what Spender wrote, of how the loftiness of Goyen’s ideals sometimes threatened to suffocate what was human about him.

Joyce Carol Oates once called Goyen “the most mysterious of writers . . . a spiritual presence in a national literature largely deprived of the spiritual.” These days he’s not much read, but he remains a kind of saintly acrobat, daring those who come upon him not to imitate his style but to walk the high wire, fall down, go back up, and walk it again.

I did discover an unexpected trace of William Goyen in Trinity. On my second day there, I spent some time talking with a man named Dan Barnes, who is the vice president of the Trinity Historical Society. He’d never read any of Goyen’s work—“My brother’s probably the only one in the family smart enough to read it,” he said of The House of Breath. He knew of the book, though, and he’d even wondered whether a certain property belonging to his family “was the original house of breath.” (A professor he’d talked to had disputed that theory.) I mentioned my search for the bygone trestle bridge, and he told me a story.

His father had been a doctor, Barnes said, and as a young man, working in Houston, had become enamored of a woman whose appendix he’d removed. They started to date, and eventually he drove her to Riverside to meet the family. “It must’ve been quite a ride. It would’ve been half dirt roads,” Barnes said. “She comes over this clay cliff and yells out, ‘Stop the car!’” The woman, who would become Barnes’s mother, had seen the trestle bridge spanning the Trinity River and balked. “She said, ‘I’m not going across that.’” Not in a car, at least. “So she walked into Trinity.”

Needless to say, I was surprised to hear this from a man unfamiliar with Goyen’s writing. Could Barnes’s mother have read Goyen, or heard the story some other way, and remembered it as her own experience? Could Goyen have appropriated another family’s story as his own? Had every woman in and around Trinity County been terrified of that bridge and determined to creep over it on foot?

Why do certain stories stay with us? For all sorts of reasons—because they’re attached to places or families, because they speak to character or tell of something unusual or haunting or wonderful—but in the endurance of some stories there’s also something inexplicable. Here’s this tale from almost a century ago, of a young woman in a car who demands to be let out so that she can walk herself across an unsteady bridge. Why it resonates, I don’t fully know. What are these stories we tell and how do they make us the people we are? These questions, which burn underneath so much of Goyen’s work, can’t ever be answered directly. The only way of answering is to keep telling.

- More About:

- Texas History

- Books

- Longreads