Among the jittery, beautiful, and provocative thoughts that drift through the mind of the protagonist of Dallas writer Ben Fountain’s 2012 novel, Billy Lynn’s Long Halftime Walk, is this challenging eruption: “So put that in your fucking movie, if you can.”

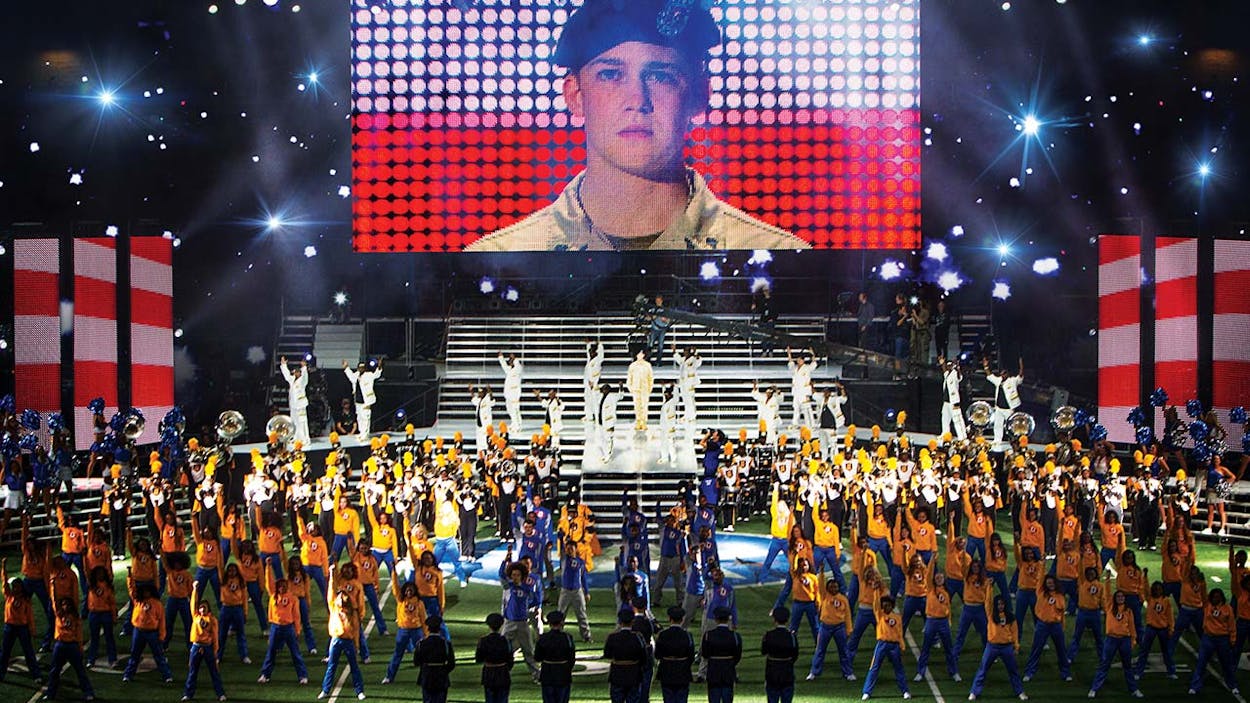

Well, on that note, good luck to director Ang Lee, whose big-budget film version of Billy Lynn will be released on November 11. It’s not hard to understand what attracted Lee to the project. The novel, which won awards from both the National Book Critics Circle and the Los Angeles Times, is concise and poignant and pyrotechnic. It takes place in 2004 over the course of a feverish Thanksgiving Day at Texas Stadium, during a Dallas Cowboys game featuring a halftime concert by Destiny’s Child. Caught up in the extravapalooza are nineteen-year-old Billy Lynn and his fellow members of Bravo Squad, who are being overbearingly honored and exploited at the game for their heroics in Iraq—heroics that a manipulative producer is racing against the clock to package as a movie deal.

The book is inherently cinematic and just as inherently not. There’s plenty of outward spectacle, but what makes Billy Lynn’s Long Halftime Walk such an unforgettable novel is the quiet, bewildered consciousness at its center. Fountain somehow got away with creating an interior voice for Billy that is innocent and naive but at the same time fully equipped with a bracing, all-observing cynicism.

In early September, Fountain talked about the difference between being the author of a novel and the creator of a property.

Stephen Harrigan: I haven’t seen the movie yet, but presumably you’ve watched at least a rough cut. Are you thrilled? Disturbed? Bedazzled? Disoriented?

Ben Fountain: The only thing I’ve seen is the trailer that was released a couple of months ago. As far as I know, no one has seen the entire film in finished form. Ang is still stirring the pot and might well be right up to the premiere.

SH: What about the screenplay? Have you read it? Did you consult with Jean-Christophe Castelli, the screenwriter? Or was it better for your novelist’s equilibrium just to stay out of the process?

BF: I stayed out of the whole movie-making process, except for a couple of dinners with Ang when he first began working on the movie and a one-day visit to the set while it was being filmed at the Georgia Dome, in Atlanta. My feeling throughout this whole thing has been, the book is the book, and no matter what the film is or isn’t, the book is still going to be the book. It helped that I had a great deal of faith in the Ink Factory, the production group that became the prime movers behind the movie. And, of course, when Ang came on board, I knew we’d gotten a filmmaker of extraordinary ability.

SH: One of the ways it seems to me that the book is still going to be the book is the untranslatable precision of its prose. The movie has been filmed not only in 3-D but in 4-K resolution, with a warp-drive frame rate that’s supposed to give the viewer a sense of hyperreality. But it’s hard to imagine anything more hyperreal than a line like “Dreams came and went like fish drifting through the wheelhouse of an old shipwreck.” Do you wonder if, when you finally see the movie, it’s going to seem more strange to you than familiar?

BF: I expect it’ll be both at once, strange and familiar, which I’m hoping will be a weird and interesting experience in itself. I mean, I sat down at the kitchen table one morning in the spring of 2009 and started to write this story in my head, about some soldiers at a Dallas Cowboys halftime show. I knew there would be the halftime scene and the opening scene in the limo; other than that, everything was vague and uncertain. My editor had turned down a novel set in Texas about four months before and urged me to write something other than this soldier story I had in my head. The Iraq war was “old news” by that point, and she saw a tough sell ahead, and that’s assuming I even managed to turn in a halfway-decent book. But about the only thing I had the wits to focus on was the story itself, and trying to write it properly, and the hell with everything else. The very last thing on my mind was any thought that it might be a movie someday. I wasn’t even sure I still had a career at that point, if you can call one fairly skinny book of short stories a “career.”

So the whole movie thing is pretty much a lark. I’m just tagging along for the ride and enjoying it. When people ask me, “How are they gonna do this in the movie? How are they gonna do that?” I just laugh and say, “It’s not my problem.”

SH: I applaud your arms-length strategy, but it’s hard to believe you didn’t have at least some close-up experience with the movie business to draw on while you were writing this novel. Your depiction of Albert, the producer who is frantically trying to put a movie deal together about Bravo Squad’s heroics at the Al-Ansakar Canal, screams authenticity.

BF: At the time I wrote the book I’d had only a few glancing encounters with the movie business. Enough to give me the impression that a lot of it takes place somewhere on the ethical level of drug dealers and pimps. To get a better sense of that world I read a couple of books and talked to a friend who’d been in the business for a while. And I’d spent five years practicing real estate law in Dallas, so I had that to draw on as well, a certain amount of experience dealing with big egos and big deals.

SH: The novel is very visual—at times the pages even read like jacked-up concrete poetry. Has the power and pace of movies had an effect on your writing?

BF: I wasn’t thinking much about other books while I was writing Billy Lynn, but a person who did seem to be on my mind a lot was Robert Altman. Just the feel and tone of those ensemble movies he did [Nashville, Prêt-à-Porter] that take place around big public events, and the way all these people are interacting with one another but not really, because each person is so focused on their own agenda they aren’t really connecting with anybody else. So I was thinking about him and using my memory of those films as a rough guide, more the way they felt than anything else.

SH: And like Altman movies, your novel seems liberated from overthought ideas about plot and story structure. It just unfolds in a steady, ordained sort of way.

BF: Yeah, there’s not much plot to it, is there? Whether the movie deal is going to happen, there’s that, and whether Billy is going to go AWOL, that’s another sort of plot engine. But mainly the story is what happens to the Bravos as they experience the day at the game, their last day stateside before they go back to the war.

While I was writing it I was thinking, “Well, it might be a lot more elegant if there was more of a plot,” but I got over it. Just telling the story as it came to me seemed like enough.

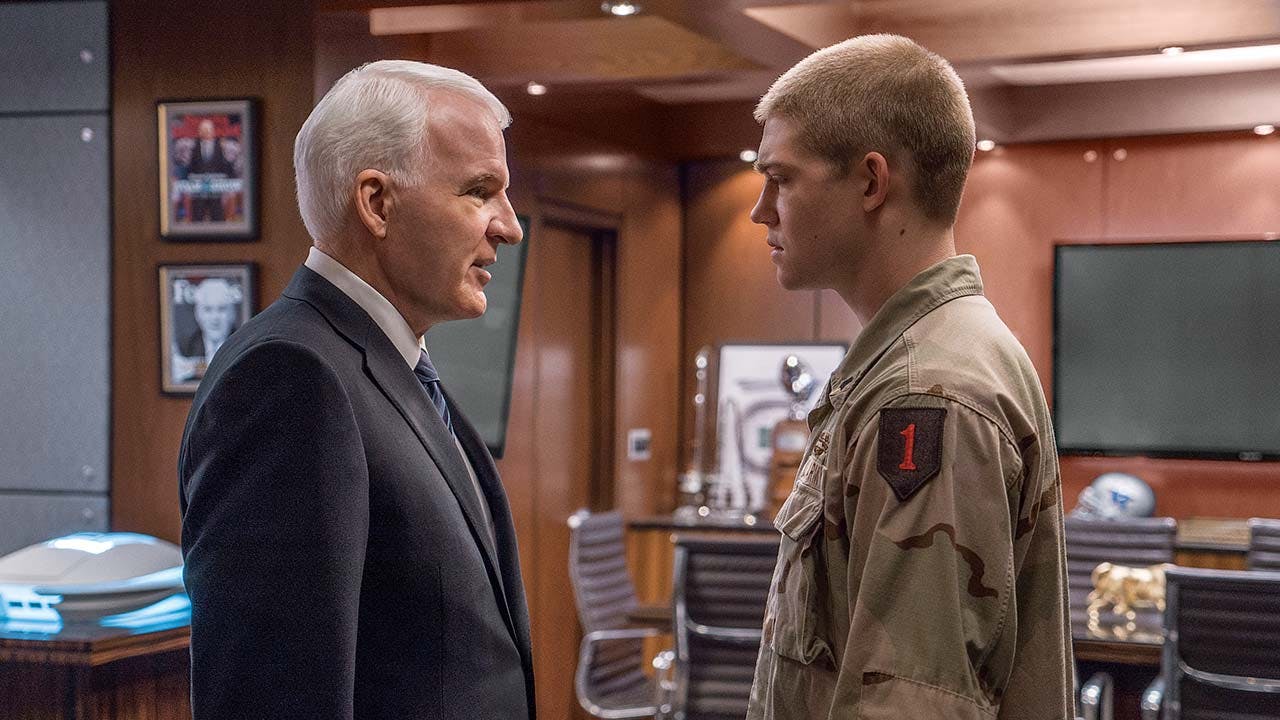

SH: Did some of the casting choices surprise you? I would never have pictured Steve Martin as Norm Oglesby, the ultra–alpha male owner of the Dallas Cowboys, or action star Vin Diesel as Billy’s squad leader, Shroom, who is described in the book as “a fleshy, slope-shouldered, melanin-deficient white man with the basic body type of a manatee.”

BF: I can’t say I was much surprised by anything, because I didn’t have any expectations. I had no experience to base any expectations on, but I think I can see the logic behind all the choices. Kristen Stewart as Kathryn, I think that’s a tremendous choice—by this point in her young career it’s clear she can play just about anything. Steve Martin can do genial menace quite well, and Vin Diesel’s unique looks seem striking enough to put him in the same league of uniqueness as Shroom. I like the idea of Chris Tucker as Albert a lot. In the movies of his I’ve seen, there’s this subtext of desperation and anxiety underlying all the energy and laughs, the sense of a guy pedaling very hard to keep from falling over.

Joe Alwyn, of course, is the real surprise, but I figured if they were going to do this right, they’d have to find somebody completely unknown to play Billy. You want the audience to come to him with a blank slate, with no baggage or association from past roles. I got to spend a little bit of time with Joe, and I very much got the sense that they’d found the right guy in terms of looks, presence, soulfulness, and acting chops.

SH: The movie is a bigger production than the game you describe in the book. Is it weird to realize you’ve employed more people than Norm Oglesby?

BF: That day I spent on set at the Georgia Dome, I remember walking with my son into the bowels of the stadium, passing through all this activity—delivery trucks, security guards, drivers, carpenters, electricians, food-service folks, and the like—and then entering the stadium and seeing what seemed to be at least a thousand people there on the set: the crew, actors, the football teams and coaches, cheerleaders, security people, and the army of extras up in the stands for the crowd scenes. I just kind of laughed to myself: All of this came out of my head? Because I sat down at my kitchen table one morning and started trying to write this story that was banging around in my brain?

Life is weird, sometimes in a good way. That was definitely one of those good weird experiences in my life.

Though I think Norm Oglesby has me beat by a mile on number of people employed.

SH: I agree with what you said earlier, that after the movie comes out the book will still be the book. But there’s got to be a part of you that’s thinking, “Whoa, the book is now also this, and it’s something that’s no longer mine.”

BF: It’s weird, but I haven’t felt like the book was mine for a long time. It came out of my head, sure, I wrote it, that’s a fact, but once it’s out in the world, it becomes its own thing. I feel a sort of detachment about it all, and not in a bad way. I’ve moved on.

SH: Writers are solitary practitioners. In fact, writing a book is a process of conditioning yourself to privacy. It can even feel like an intrusion when the book is finally published and total strangers start reading and reacting to it. Now here comes this gigantic shock wave of a movie bearing down on you. Please tell me you have a survival strategy.

BF: My survival strategy is to have hard and interesting stuff to work on, and to focus on that. I’m completely happy to sit down at my desk for five or six hours a day and do my work, and in fact, I’m miserable if I can’t do it.

SH: Are you tempted to write a novel based on the making of this movie based on your novel?

BF: I get the sense that the movie business is a world in itself—no, worlds within worlds within worlds in an infinite regression, with varying levels of reality and illusion, not to mention delusion. That’s fertile ground for a twisted mind like mine.