In September 2017, I entered into an unusual correspondence with the sculptor James Surls. It began typically enough. He wrote me in the hopes that I’d cover one of his upcoming exhibits, and I replied with a short note, something vague about keeping in touch. That gave way to a series of emails, arriving every week or so, expounding on a variety of projects. He had a lot on his mind, it turned out: process, viewpoint, business. Often, though, the dispatches seemed encoded. “I am the bird standing on the cedar stump,” he wrote in one. “What makes the clock think out loud?”

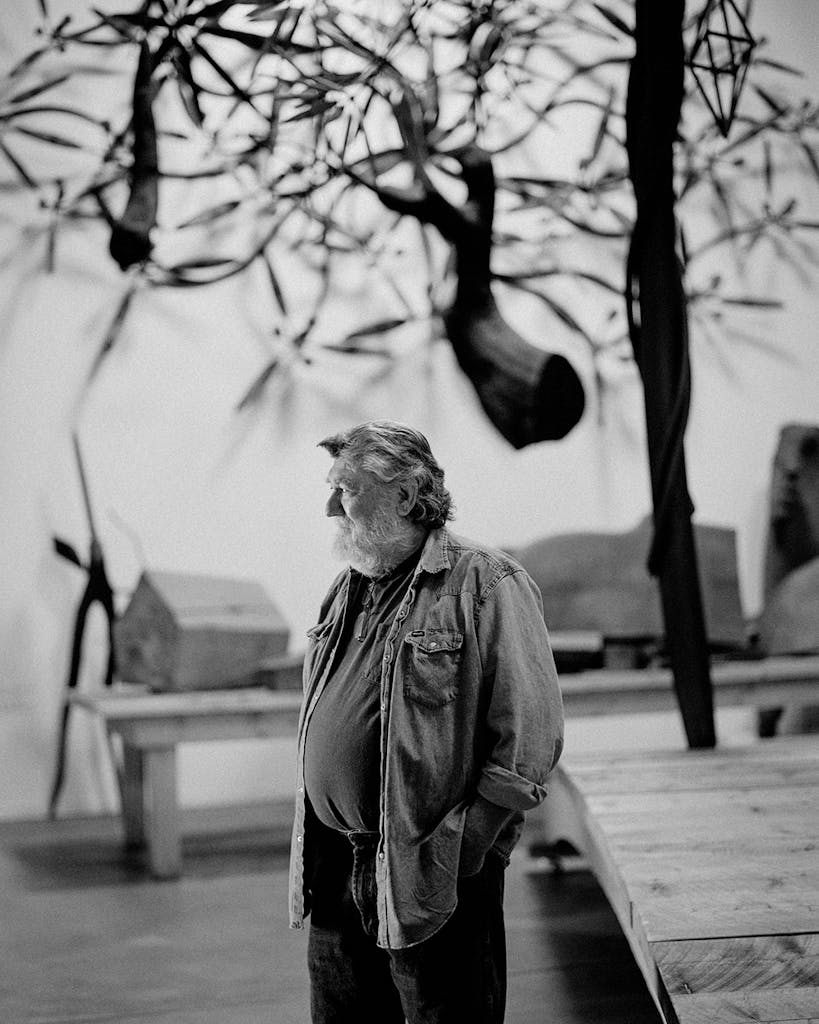

I couldn’t help but wonder: What the hell? Surls had been as prominent a figure in the state’s art world as Troy Aikman was in Texas football. In the 1970s, he emerged like a folklore hero, the Paul Bunyan of Texas art, an enormous, burly man with long hair, deer-antler-tip earrings, and an ax, for sculpting, by his side. At a time when out-of-state curators were starting to take an interest in Texas, Surls’s art played a role in defining the scene, and, like him, the work was big and spoke in metaphors and riddles. (A piece from 1980 called “Needle Man” is a serpentine, corkscrew piece of wood about nine-and-a-half feet tall with eyes, an open mouth, and spikes coming out of its head, if that gives you any idea.) Though he never achieved the kind of national recognition Texas-raised artists like Julian Schnabel enjoyed, he was collected in most major Texas museums. He was a macho artist, one whose persona might seem carefully manufactured if he weren’t so earnest. As another Texas artist would later tell me, “He was a big deal because he couldn’t be anything else but a big deal.”

The emails continued. Once, he responded to a message of mine with, “I appreciate all things, time is my friend, I am going to lunch.” Another time, he wrote about an installation of seven works going up in the Dallas-Fort Worth airport’s international terminal, where thirteen million people would see it each year; the opening, he promised, would “have more bigwigs than you can count. We are talking fu-fu la-rus from the whole of North Texas and beyond.”

What casual interest I had in his emails had grown by this point. Here was a man who many considered Texas’ greatest living sculptor, now in his seventies, trying to articulate his path or. . . something. Surely there was some insight to be gained from his moments of reflection, if only someone could translate these emails. Whenever co-workers passed my office, noting my mixed looks of confusion and fascination, I would motion to my computer screen and read something Surls had written, such as: “I am the elephant man remembering the glean of reflections from the surface of still water. . .” My co-workers would—slowly, politely—back away.

The emails weren’t all oblique metaphors. Threaded through them were internal conversations, almost like diary entries. Surls had initially written to tell me that in November of last year, he was opening a show titled “Through the Thorn Tree” at Dallas’s Museum of Biblical Art. His friends disapproved of the show, he explained. Some were atheists who bristled at any religious institution; others felt that sliding Surls’s work into a Judeo-Christian box limited its spiritual scope. And so he felt obliged to explain why he would exhibit his work there. “I am compelled at every turn, at every consideration to do the show,” he emailed, and then applied some dizzying logic. “It is like, ‘If I were me, being me, looking at me as me, I would like me.’ But if I were me, being me, looking at me as somebody else, then I don’t know how much I would like me doing what I am doing.”

I would later find out that some of his friends’ concerns had little to do with the religious cast of the show and more to do with the chess game of managing a career. Continuous small shows, like the one at the Museum of Biblical Art, have a potential to chip away at an artist’s time in the studio, time that could be spent building a body of work. Holing up in the studio is easier said than done, of course. International art stars have the capital and the staff to iron out the business deals; they have already sealed their names in the canon, allowing them to focus on studio time. Lacking the money, the staff, the solidified reputation, Surls had to strike a balance. But he was in the last phase of his life’s work now, and the clock was ticking. Maybe this is why he started writing emails to me, in a fit of self-promotion. It’s also why I took the bait and agreed to meet him in Dallas. I wanted to know what this last phase of a career felt like.

A few hours before his Dallas show opened, I finally met Surls, who’d been waiting for me inside the museum, in a dramatically lit atrium surrounded by tall arches. He’d maintained his imposing size, with beefy fingers that betrayed their callouses by issuing an audible “swoosh” whenever he brushed his hands along the sculptures—something he tended to do a lot. But if his appearance still had a Paul Bunyan quality to it, he didn’t look like a hippie anymore. He’d boxed up his antler earrings and cut his hair short, framing a face recognizable every so often in Surls’s line drawings: wild eyebrows set atop narrow eyes, the wide jaw and thick neck of a quarterback.

In a booming baritone that echoed in the gallery, he apologized for a terrible cold and began guiding me through the show, stopping at a few drawings and sculptures for a short discussion as museum workers drilled mounts into the walls for last-minute hanging. The themes in his work were apparent from this small survey: flowers, thorns, sex, churches, boats, cows, eyes, totems. I quickly learned that, unlike some artists, he enjoyed talking about the work, sometimes correcting “wrong” interpretations. (At one point, I called something a “church” and he said, “That’s actually just a house.”)

“This is called ‘Rough God,’” he said, stopping in front of a steel work he made about ten years ago. With foot-long spikes shooting off a long, curving stem, it brought to mind a thorn bush, about waist high, precariously balanced on the floor. “We can subscribe to very lofty things but boy, humanity can just really do some pretty nasty stuff. So I thought, okay, how do you explain that if you are ‘a God person?’”

A few feet away from “Rough God,” he stopped near a sculpture hanging from the ceiling: a square of stone surrounded by a steel flower, a wood flower, and a giant wood phallus. “This one is called ‘Knowing What the Stone Knows,’” he said. “It’s a stone that I got out of the riverbed and you stand there and you look at the river and you look at the water flowing over the stones and man, they know so much.”

Surls kept circling back to the question of why he’d done this show at all. Every time the topic arose, he shifted his feet and sighed. His work was spiritual, he argued, so why shouldn’t it be here? And from the beginning of my time with him till the end, he talked about the cycles of public interest and how he fit in that cycle. Terrie Sultan, former director of the Blaffer Art Museum, in Houston, once wrote that Surls used “diamond shapes, whirling vortexes, needles, knives, and horses—infused highly personalized folk idioms with the aesthetics of high modernism,” a description that may sound dynamite to an outsider like me, but apparently it’s not the type of thing that sets the “high art” world into a frenzy.

Over the winter that followed that first meeting, he sent me more messages. “Thoughts are effected by the gravitational forces of the Universe like the tide pools rise and fall with the moon. All things are possible and nothing ain’t nothing,” he wrote.

Just in case that viewpoint was too cryptic, though, I could focus on the more accessible truths: “Sheep move in flocks, birds move in a flock. Turkeys are birds and move in flocks.”

Not long ago a graduate student asked Surls whether he touched his art. He was shocked by the question, but immediately realized that his surprise showed his own naïveté, since sculpture had been veering away from craftsmanship for a long time. Many sculptors now draw their plans on paper and, like an architect would, hand it over to a person or team for execution. Surls has an assistant who helps him bend pipe and cast components, but he still touches everything. “I may be the last man standing in a whole epoch of time,” he told me. “I kind of hate to say that, but it’s true. I mean, what do I do? I get up in the morning and make art. I chop and rash and saw.”

The chopping and sawing can be traced back to Surls’s childhood in Malakoff, southeast of Dallas. As a boy he and his older brother, Larry, often worked with their dad, a construction worker, on their property, clearing brush, making fence posts, building bridges and barns. “My youth was spent in the woods,” he said. “I played in creek beds and made little roads and castles. It was my territory. Those trees were my people.” When his mom was absent—as she was, from time to time—he and Larry would help their little sister, Melissa, washing her hair and setting it in rollers.

As James grew older, he was unsure how to forge his own path outside the shadow of Larry, who’d become a young titan of Malakoff, a football star voted “most handsome” who could also build hot rods. James held some influence (once, in a rebellious mood, he cut the belt loops off his jeans, and all the boys in school followed suit) but for a while he didn’t settle on any particular goal. He started at Henderson County Junior College, in Athens, intent on becoming a football coach; later, after studying anthropology at San Diego State University, he dropped out to make money selling cars, until he finally moved back to Texas to finish a senior year at Sam Houston State University, where, lacking any better ideas, he planned to graduate and sell life insurance.

Instead, he seized upon a career thoroughly lacking security. It was just a day or two before registration, while walking through Sam Houston’s campus, when he noticed a man too old to be a student sawing into a big pine log. The man sized up Surls and asked if he could use a chainsaw. “I want a cut here and here,” the man told Surls, pointing to imaginary lines on the log. Of course, this request posed no problem for Surls—he was a big East Texas guy and by this time he was like a bionic man with brush-clearing tools. He made the cuts easily, and the man introduced himself as Charles Pebworth, the university’s sculpture teacher. Pebworth was an outlaw of sorts, and, as is often the case with the smaller state colleges, the art department at Sam Houston was filled with renegades just like him, people who didn’t know the rules of the proper art world well enough to recognize that their approach was nonconformist.

This boded well for Surls; he didn’t know the rules, either. Within the week, he had made a realization that changed his life, one that is novel for anyone who grows up outside of a city: he could make a career by creating interesting things. With most of his core classes behind him, he had little else on his agenda. “I had some miles on me. I’d been out in the world. So where else would I go?” he said. “Charles Pebworth was extraordinarily available. I used his studio and I made art all the time.” Inspired by the Mexican muralist José Clemente Orozco, he painted large, expressionist works featuring farm imagery; in sculpture, he carved abstract forms out of wood, some already approaching seven feet in height.

Art would be his life, he decided, though how to achieve that goal was as mysterious to him as it is to every burgeoning artist on the planet. On a whim, after graduation, he applied to the esteemed Cranbrook Academy of Art, in Michigan, and studied there for a few years, but when he finished and moved back to Dallas, he found himself lacking all the necessary space and tools he’d need to cast metal and chop his large works. In that first year after Cranbrook, he didn’t do much work at all. Mostly, he worked in welding shops around Dallas and wondered how he was going to get back to making art. It wasn’t like someone was just going to walk up to him and offer him a job as an artist.

Except that’s what happened. While sitting on a bar stool at a little blues nightclub called the Blackout, he got to talking to the man next to him, and a conversation unfolded that went something like this:

Man: “What do you do?”

Surls: “I’m an artist.”

Man: “What kind of art do you make?”

Surls: “Sculpture.”

Man: “Really? I’m the sculpture teacher at SMU. I’d really like to take a semester off. Would you like my job?”

He did. And his luck didn’t end there. Soon afterwards, in 1970, a sharp, pretty psychology undergraduate named Charmaine Locke attended a Southern Methodist University faculty show and noticed a wooden cradle made by the first-year sculpture teacher James Surls. Seeing it across the room, she was mesmerized. She walked closer and saw the name on the label. She didn’t know anything else about the sculptor. But she was a senior with most of her core classes fulfilled, and, needing a few more credits, she decided to enroll in Surls’s class.

Neither Locke nor Surls relishes the story of their romantic beginnings due to the pain that it caused others. They were both married at the time, he with three daughters. And yet they couldn’t suppress their immediate, unambiguous attraction. He had never included another person in his artwork before Charmaine, but after reading her papers and seeing her raw talent, the impulse to involve her in his life—and his art—was unavoidable. “The biggest influence of my life is Charmaine Locke,” he said. “She’s in all the work—even the ones where you don’t see her.”

She would remain on his mind the following year, when he spent the summer teaching SMU students in Taos, New Mexico. At the foothills of Kit Carson National Forest, one can look out over the Rio Grande Valley for miles and see gorgeous vistas, mind-bending sunsets of purples and oranges, pinks and blues. One day, while walking in those foothills, he spotted a particularly beautiful vantage point. He took some two-by-fours and built a square form. Then, in the hot sun, he poured a concrete slab. It would have no walls or roof, but for that summer, it would become his studio.

There, on that platform, he watched weather systems move in and out of the valley, inspiring in him a meditation on sticks and trees and water, rocks and sky. During a three-month period there, he created seven large pieces that formed the core of his first major period, works like “I Saw a Man With Shovels in His Hands Scooping Fire from the Sky,” a nine-and-a-half-foot-tall, nine-and-a-half-foot-across spaceship shape with legs and arms outstretched, and shovels as hands, and “She Brings Gifts to Me,” a wood figure the size of a person (based on Locke) that sprouted spotted wings and reached forward with stubby fingers. He was learning a new language, a new way of creating. “I was divorcing myself from my ability to only work in real,” he said. “I was starting to put the thickening in the soup.”

By this time, the meaning of “sculpture” had broadened. Under that heading, artists created earthworks, conceptual light and space works. Surls didn’t fit into these categories, just as he didn’t fit in with “pop” or “assemblage.” But he understood the context in which he operated—and now he knew better what he could contribute.

He was suddenly prolific, and collectors began noticing his work. He was showing pieces at the Tyler Museum of Art and the Little Rock Museum of Art. Soon enough, Harry S. Parker III, then the director of the Dallas Museum of Art, bought one of Surls’s pieces for the DMA (a steal at $250—still, it was a boost to his self-esteem). Parker, along with Janet Kutner, the art critic for the Dallas Morning News, and the artist Jerry Bywaters, championed Surls, and soon the town was buzzing about the talented man with an ax.

“I may be the last man standing in a whole epoch of time,” said Surls. “I kind of hate to say that, but it’s true. I mean, what do I do? I get up in the morning and make art. I chop and rash and saw.”

Around this time, art lovers were taking some interest in the region around the Gulf of Mexico known as the “Third Coast.” Out-of-state curators from major museums were visiting galleries and studio spaces, noting Texas’s momentum—specifically in Dallas and Houston. It was as if someone had pulled back a curtain around the state’s perimeter, and Texas artists found themselves onstage.

But by the mid-seventies, a more noticeable shift would come from within the state. Surls had felt some vindication from his Dallas successes, but they couldn’t compare to the anointment ahead when he was introduced to the new director of the Contemporary Arts Museum of Houston: Jim Harithas.

To call Harithas a force would be an understatement. Harithas, who’d just been fired from his previous job and was married to artist and oil heiress Ann O’Connor Robinson, had curated one-person shows for major art stars like Yoko Ono, Nam June Paik, Joan Mitchell, and Norman Bluhm, and he had a confidence and addiction to risk that was as rare then as it is now. Perhaps more importantly for Houston, he was also geographically egalitarian, and when he moved to Texas, he preached the novel concept that the state’s art was as important as art anywhere. “Nobody from Texas at that time—with few exceptions—would have anything to do with Texas art no matter what they may try to tell you now,” the painter John Alexander told me. “It was as if it didn’t exist.”

While taking a tour around the state, Harithas walked into Surls’s Dallas studio. The work was composed, at the time, of bristling totems and tribal-looking objects. Harithas didn’t say anything, he just looked around. Then he said, “Well, you’re ready.”

Knowing that Harithas was offering a show at the CAMH, Surls tried to remain calm. “When do you want to do it?” Surls asked, assuming Harithas would give a window of two to three years.

Harithas thought for a moment and replied, “Six weeks.”

Surls felt the shot of adrenaline that only a show date could provide. That solo exhibit in 1975, curated by Paul Schimmel, who later became the chief curator at the Museum of Contemporary Art in Los Angeles, featured 85 works. “It was one of the most cluttered exhibitions I had ever seen,” Harithas said in an interview for one of Surls’s books, “but it looked beautiful.”

The show was a game-changer. While few people bought the works, Surls received accolades by the tonnage, convincing him he needed to move to Houston. “I got told I was wonderful about a thousand times,” Surls told me. Artists, collectors, gallerists—they all gushed. “My God, if you could just eat wonderful.”

The Houston scene, at that time, mixed social groups. At any art opening, half the room, dressed in cocktail attire or high fashion, would mingle with artists dressed like hippies, punks, and gypsies. Picture women in crocheted jumpsuits dancing to Clifton Chenier—the scene was like that. This was a time when the oil boom was in full swing and NASA was animating the city with modern sparkle. Philip Johnson’s buildings were going up. New offices were opened at a breathtaking pace, and those walls needed to be filled with art.

While Surls was plenty social and liked people, he needed more space than he’d had in Dallas, where he could see others’ front doors when he exited his house. He needed an acre. Two acres, maybe a little more. Eventually Locke found the right place for them, a one-room shack on 22 acres of dense forest northeast of the city. This was in a town called Splendora—a name that would eventually become shorthand for the most important chapter in Surls’s career. “I went to Splendora in love,” Surls said. And he wasn’t just in love with Locke, he explained, he was in love with the romance of what their life was going to be. “I lived down a road, across a bridge, around a curve, on a hill, in the cabin in the woods.”

Of course, living in an un-air-conditioned little cabin is only charming for a short period of time, and so Surls began building rooms on to the cabin to adjust for their growing family, which all told included seven daughters—four of their own and the three from Surls’s previous marriage who visited on weekends and holidays. The compound grew along with his legend. Even those who are suspicious about the romantic man-myth that Surls represents would have a hard time resisting the enchantment of this period in Splendora. Locke designed a house decorated with pink disk-shaped glassware from the thirties and forties. The girls would run through the woods, exploring as he once had. One bedroom was a treehouse. At some point, Surls’s mother and stepfather moved onto the property, and by the early eighties, he’d built a 12,000-square-foot studio where root systems and wood chunks the size of a small car were piled up, awaiting transformation. The place had grown such a reputation by 1988 that Architectural Digest featured it in a photo spread.

When he wasn’t teaching at U of H or working on his art—which now included drawing—he and Locke would head into town to attend gallery openings, where an energetic arts scene was forming. Harithas brought in major figures like Willem de Kooning and Norman Bluhm to mingle with the local artists; he also connected local artists to curators and artists in New York, building a bridge to the international arts scene. Soon, then-unknown University of Houston students Mel Chin and Julian Schnabel would begin showing their works.

In Houston, Surls hit his stride. The sculptures became larger; many hung from the ceiling, and often portrayed creatures with eyes—sprites and other supernatural-looking beings. He was included twice in the Whitney Biennial—first, in 1979, with “Me and the Butcher Knives” and “Night Vision” in a large room, and again in 1985, when two massive works called “Man Doing War” and “Woods Angel” showed in a 50-square-foot room alongside only Jasper Johns and Donald Judd. His reputation was growing. Harithas once said, “He is one of the great artists of the state. He ranks with Robert Rauschenberg and Myron Stout. As for art history, Surls’s work represents one of the first big challenges to minimalism. This is his legacy, as far as I am concerned.” The directors of the esteemed Marlborough Gallery in New York City gave him a show—the equivalent to playing Carnegie Hall. He even curated a show at the CAMH, after Harithas’s ouster, a firing precipitated by a now-legendary exhibition opening party wherein a 200-foot wall of bread loaves spurred a food fight, then a fistfight, eventually necessitating a visit from the police.

This was a magical time in Surls’s life. “I actually had dreams of being seen from outer space by alien types of life, life from somewhere else, receiving a life from somewhere else. Messages. I don’t think that ever happened for real. I don’t think I really got a message from a space alien. But I think I got a lot of messages from the deep universe and they were just personal. They were things like poems and writing and it was a very creative time, I’ll tell you. I loved it. I call it the glory days.” And his own work was just part of the joy. “You know, during that period, I started Lawndale. Man alive. Lawndale was a living creature and had a life of its own.”

In 1979, the U of H art building had burned down, and the oil field services company Schlumberger offered the university an abandoned warehouse on Lawndale Street, an unorthodox suggestion that another university might have rejected. But U of H accepted. Soon, an administrator called Surls apologizing, “We’re sorry, Mr. Surls, we know you have to endure this for several years, but we’ll get through it.”

Surls was elated. The space was 100,000 square feet with a 40-foot-tall ceiling and truck doors. “You couldn’t hurt it,” Surls said. If he needed to paint the whole thing black inside, he could do that; if he needed walls or stages moved, nobody stood in the way. The massive warehouse offered him flexibility; it allowed him to entertain ambitious ideas on which no museum or gallery could gamble. As the person in charge of exhibitions, he started giving student shows once a week; soon he was making space available to non-students. “I became like a magnet over there,” he said. “All I had to do was sit in a room and say ‘yes.’”

The first thing he said “yes” to was a show of about a thousand miniature works from Louisiana and Texas and Oklahoma, an exhibit Surls co-curated with Bert Long, a fellow artist Surls met shortly after moving to Houston—and who continues to loom large in Surls’s life, though he died in 2013. Long tended to toss around big ideas like, “Let’s drag an iceberg into the Gulf of Mexico.” He had one pair of pants and one shirt that he washed each night. “All cylinders were beating on the love of task, the desire to do something,” Surls said. “Having that as the fuel that drives your train? That’s powerful.”

In short order, Lawndale became a scene. One of the most memorable shows was another co-curated by Surls and Long—called “Pow Wow,” it included around 500 miniature works, belly dancers, magicians, and a cake-decorating contest (never mind that Lawndale lacked air conditioning and icing would melt, along with visitors’ makeup). According to Pete Gershon, author of the book Collision: The Contemporary Arts Scene in Houston, the proposal Surls and Long wrote to try to fundraise for the event “just goes on for pages and pages, and these guys were just dead serious about it. They wanted to do the biggest, best exhibit ever. And I think that was just the way James’s mind works—it certainly did back then, when there just seemed to be absolutely no limits.”

People who remember the early Lawndale years say there was nothing like it before and there hasn’t been anything like it since. While the Lawndale Art Center still exists and hosts great exhibits, its early success gave rise to a more formal structure—a board of directors, for example—that tamed its spirit. Surls himself only lasted four or five years at Lawndale before it tired him out and he relinquished control, but he continued teaching for another few years, recruiting up-and-coming artists like Jack Massing and Michael Galbreth of the Art Guys, Sharon Kopriva, and others.

More than coaching them on technique, they say, he led by example and demonstrated how they could make a living as an artist. He told them about a “blue box with many doors” he imagined above his head, where ideas could pass through safely, without judgment. He told them to keep a low overhead, he warned them not to be slayed by those mundane dragons called car loans and mortgages. He stressed the importance of full-steam-ahead work ethic over griping and ponderous planning. Massing told me, “He was always working toward the future that didn’t exist yet. He told us, ‘I don’t care if you have a gallery or a museum looking for your work; it’s gonna happen if you’re making work. It’s gonna happen, so just be ready for it.”

Surls could have stayed in Houston for many years—maybe forever—working in Splendora, hosting parties. But in the nineties he traded his cocoon of hot, dense forest for a Colorado aerie with views of the Rockies, where every morning he would walk down a winding mountain path as the sun rose over the distant, snow-capped peaks and pull keys out of his pocket and open the aluminum door to a new huge studio.

He wasn’t immediately enthusiastic about this transition. In 1996, Locke informed Surls that she was moving to Colorado and he was invited to come with her. Surls told me this story last spring at a diner in Austin, where he’d come to open a show of prints at a local gallery. “I think she just had it with my shit, to tell you the truth,” he said. “I don’t think that meant she didn’t love me. . . It didn’t mean that she didn’t want what we had, but we didn’t have what we started with—we now had that inflated times one hundred. She wanted to simplify it.”

Locke is still amused by Surls’s surprise at the announcement. She recalls that they had talked about moving for a year before she voiced an ultimatum. But more than twenty years later, Surls still seemed stunned. Locke was not just his partner—she was his muse. “I mean, what do you do when the person you love most in the world says, ‘I think we need to move to Omaha?’”

“She could have told me I couldn’t come,” he continued, fiddling with his wedding band, now engraved with seven eyes for seven daughters. “She could’ve said, ‘I’ve had it with you and your inflated bullshit.’ But she didn’t. Charmaine was the best thing that happened to me in my life, still is.”

Arguing that he wasn’t ready, he stayed in Splendora with his youngest daughter, who was in junior high, and Locke moved with the three who were older. (Surls’s daughters from his first marriage had graduated from high school by this point.)

The result was predictably awful. A few weeks after Locke moved, Surls quit going to social events. He couldn’t bear the refrain: Where’s Charmaine? “I cried every day for six months. Literally, it was horrid. But I was not going to give up on the love of my life. I mean, I had staked my very being on her, had put everything I had in her basket, and in all fairness to her, she had stuck with me. You know, I didn’t have anything to prove other than the fact that I loved her and that was it.”

In time, he realized Locke was not going to announce a change of heart. She was not going to pull up to the compound with all the luggage on top of the car, as if they’d all just taken a long vacation. He also wasn’t going to sell Splendora; he’d put too much work into it. But he would have to move north. So he began packing up his tools and giant logs, and he left their fairytale house in the woods down a road, across a bridge, around a curve, on a hill.

Just how Colorado had changed him, in the decades and miles that he’d put between him and Splendora, became a recurring theme in our conversations—in his encoded emails, in person, and on the phone. Staring out at a mountaintop rather than a dense thicket has a way of changing the art, making it sleeker, expansive, more about particles and space than totems and woods. And with limited years remaining in his career, he said, he needed to decide which works would receive his dedication and time, which would be put on hold, and how those selections would secure his place in history.

Last winter, when I pulled into the driveway of Surls’s Carbondale, Colorado, home, just a short walk from his studio, he walked out his front door wearing his typical work uniform: jeans, blue suspenders, and a blue denim shirt with rectangular, wire-rim eyeglasses hanging off the top button. His hair had grown out a little since I’d last seen him, and he’d grown a trim, white beard. “Well, what do you think?” he asked, approaching the car as I stepped out to take in the view. He leaned back on his heels and looked out at the scenery with me. “This was just a vacant piece of land. We walked from the road over there, up over the hill, and when we got right up there”—he pointed to a spot a few feet in front of us—“we were looking out and saying, ‘Oh my gosh, are you kidding me?’ I mean, come on. We’d lived in a place that had trees everywhere.”

As Locke approached, rubbing her shoulders to warm up, Surls turned to her. “I was telling her about when we first found this place and we walked over here.”

Locke beamed and lifted an eyebrow. “It was, as they say, meant to be,” she said.

The change in his surroundings had indeed prompted an airier, cleaner series of works—outside, I could see some of his steel “molecular” pieces, like large models from chemistry class—though it hadn’t changed his blue-collar work habits. He rises around 4:30 a.m., as he always has, and writes until 7 a.m. Then he walks a short distance to his studio, where he works until exactly 5 p.m., stopping as though a whistle blew the end of the shift.

He took a rare break on the day I visited and walked me past a few works in progress, massive sections of tree trunks cut willy-nilly resting on benches outside. His studio was an 8,000-square-foot building composed of two large rooms, the first of which contained his tools: rows of axes, hammers of various sizes, clamps, rulers, and helmets and gas tanks for welding. The second resembled a warehouse filled floor to ceiling with artwork. Some were works in progress, some were completed pieces he’d bought back from people who were going to put the sculptures on the auction block, a suggestion that tends to send Surls swooping in as if the work were headed for a dumpster fire. Above and below, bouquets of thorns and flowers were set alongside nine-foot-long creatures with multiple eyes. The whole room appeared to spin, the critters to swim through the air, though everything was perfectly still.

“I really look at them as a body or a herd or a flock,” he said, touching the work as he passed, the way one would touch pets in a room, and he discussed them as if they were living things that breathed in this setting, best understood in the context of their peers, complete with shadows. “When you see them isolated, clean and formal, it’s almost like getting dressed for the ball. They’re not in their pajamas anymore. They’re not slouching around the living room, they’re kind of formal and going out on the town, and that’s what an exhibition is. It’s a way of formally making a presentation.”

He took me on a tour of the many projects he had under way. Partially because he needed to pay bills, partially because he was readily drawn to new ideas and prone to distraction, he tended to juggle many pieces at once: some for commission, some not. He didn’t feel guilty about this. Surls doesn’t have a side gig, a teaching job, or an agent. Around 2010, after the economy took a hit, taking the art market with it, Surls pulled his work out of galleries and began representing himself. This drastic move resulted in a more complete cut of his works’ sales, since he didn’t have to share the earnings with a gallerist. It also meant he had no one to blame but himself if a sale fell through. But it led to more emails and inquiries that required his daily attention. (His youngest daughter, Eva, helps in the office.)

As his own boss, he lives sale to sale, and he rides himself hard. “I look at it like this: if an opportunity comes into my head and sort of zings by like a bullet, I could miss it. And I’m sure we all miss opportunities all the time, just simply because we’re not in a position to catch them.”

Lately, opportunities had abounded and he’d been expending his efforts on massive commissions. In Lubbock, on the campus of the Texas Tech medical center, he’d be placing three big molecular-flower pieces. For the meditation garden of the Holocaust Museum and the Museum of Tolerance in Dallas, he was creating a giant explosion of flowers and eyes.

“I’ll tell you what will be as good as it gets: the possibility of making that memorial piece in the Holocaust Museum,” Surls said. “I don’t think I could ever top that, to tell you the truth.”

But while public works are highly visible and longstanding, it cannot be denied: commissions require compromise. They are creative puzzles that fit a particular space with a particular budget, sometimes requiring the benediction of a board, and the time and effort required to create commissions must be balanced with time for those works that emerge independent of any business plan. The question was how he could do all of it at once. If he was going to have a retrospective one day, at a major museum, he needed to have his own work done. If some national high-art lovers were going to “discover” him and cement him into the canon, he needed to be ready.

Surls, who turned 75 last April, tries to be careful with his time. “I think there’s no question that legacy starts to enter into your vocabulary,” he said. “Where is all this going? What will happen? You know, there’s Charmaine and seven daughters will be left, and come on. I mean, I know I would be lying if I said I don’t think about my legacy.”

“I will go on record as saying I think I have one of the most important bodies of work that’s ever been produced in this country,” he said. He readily acknowledged how nervy he sounded, but he went on. “You find another body of work like this and I’ll buy you dinner. You know, it’s all home-grown. It came out of the Big Thicket, most of it. It came out of the Gulf Coast. It came out of the western fringe of the Old South. In a lot of ways, it’s more closely related to the Southern fiction writers, you know the kind of raw circumstances of ‘Oh my God, the hogs ate Grandma.’ You know what I mean? It’s pretty rough.”

Predictably, Surls has his critics—people who just don’t like “regional work,” others who say he’s recycling, others still who say he’s too distracted to focus and dive deep into his pieces. And he has his loyal fans, who feel the same deep, intuitive response to his work as they did decades ago. Surls finds it hard to listen to anyone’s opinion. “I know I am still making some really good stuff,” he said. “You know, I think those two new pieces that are outside—and man, I’ve got three or four mortars laying in the wings that are ready to go.”

On our way out of the studio, he pointed to a few new pieces he’d had on hold while he finished his commissions: chunks of wood, giant logs. “Bert Long and I used to laugh and laugh about the phrase ‘Imma gonna.’ ‘Imma gonna do this and when I finish Imma gonna …’—you could never get all that stuff done.” Then, seemingly oblivious to having just made fun of that tendency, he began wandering through his chunks of wood, caressing them as he told me about his intentions: “I’m going to run a solid rod through the middle, and I’m going to have that piece turned up. . .” He went on like this for some time, and when we finished, I pointed to a twisted log about two or three times as big around as Surls himself, expecting a pause. He gave none, but shifted from one foot to another, leaning in as if he was glad I asked. “Well, I’ve got two possibilities with it: One is, I hang it. If I hang it, it’s going to be tough because it’s going to weigh like 10,000 pounds—”

Later this spring in Splendora, where he still visits, Surls was taking a break from a busy schedule. He’d just taken some work to a private collector in Houston and had gone to the Holocaust Museum in Dallas, he was preparing to receive an award at the Amon Carter Museum in Fort Worth, and he was going to pick up some of his prints after the show in Austin closed. Somewhere in between all this, he was supposed to fly out to El Paso for a meeting and help his daughter Ruby, who currently cares for the Splendora property, prepare for an exhibition in the studio.

While he was there, he sent me an email, informing me of all his projects and adding that now he was ready to get back in the studio, feeling “real good about the rings around my core,” and “setting in motion dreams of a higher order.”

He ended:

I just wish I were Merlin with a wand, I guess in many ways I am, except my puff of smoke with a miracle emerging from it takes months and even years to materialize. All things lead to the moment of impact, Waylon Jennings from the start had written on his traveling stage cases, “This ain’t no rehearsal,” indeed it is all live from the heart.

Green is here in Texas, the grass is high and dreams are real as rain.

James

- More About:

- Art