In 2001 Jay Hunter Morris was in Frankfurt, Germany, singing the lead role of Walther von Stolzing in Richard Wagner’s opera Die Meistersinger von Nürnberg. The part was a major break for the then 37-year-old Morris, a journeyman tenor who had spent the previous decade bouncing from gig to gig, earning enough to survive but still struggling to crack opera’s top tier. Morris was feeling pretty good about his performance until one night after the show when he was approached backstage by an elderly German man who had a small role as one of the Meistersinger. Upon discovering that Morris spoke only a smattering of German, the man became enraged.

“You don’t speak German and you think you can get up here on this stage, in Wagner’s homeland, and sing one of opera’s masterpieces?” the man fumed, in accented English, before storming off.

“I was humiliated,” Morris recently remembered. “Mostly because he was right. He had cut through the makeup. The truth is, I’m a redneck. I grew up in Paris, Texas, and I did not belong there.” The man had touched on Morris’s greatest fear: that he would be unmasked as a gauche interloper in the rarefied world of international opera. “I had the hardest time for the rest of the run getting up every day and standing in front of those people, because they all knew, and I felt like they all judged me.”

Today, Morris is considered one of the world’s leading operatic tenors. He has headlined shows at the Metropolitan Opera, the Kennedy Center, and the Sydney Opera House, as well as on Broadway. He can sing five-hour operas in German, Italian, French, Russian, Czech, and Spanish. By any objective measure, he belongs in the opera world. But that doesn’t mean he’s overcome his self-consciousness about his small-town roots. “I’m frequently nervous about not measuring up, about being found lacking,” Morris admitted. “The good ol’ boy Texas preacher’s kid is a glaring anomaly in most European opera houses.”

For the first 25 years of his life, Morris dreamed of performing at the Grand Ole Opry, not La Scala. He grew up singing in the church with his parents—his father was a Southern Baptist music minister—and decided to become a gospel singer when he was 14, after seeing Larry Gatlin and the Gatlin Brothers play at Six Flags Over Texas in Arlington. After studying voice at Paris Junior College and Baylor University, he followed that dream to Nashville, where reality quickly set in. “I learned that I really wasn’t very good,” he recalled. “Those guys, the studio players, that’s all they do. They practice all the time, they sing all the time, they’re always writing. That wasn’t me—I wasn’t that good a singer. I knew pretty soon that I wasn’t going to make it.”

One day, when he was back in Texas for a visit, a friend invited him to a production of Verdi’s La Traviata at the Dallas Opera. It was Morris’s first experience seeing a professional opera. Sitting in the orchestra section of the Music Hall at Fair Park, the Dallas Opera’s old home, Morris was enthralled by what he heard. “That’s where it hit me: that woman is lying on her back in a three-thousand-seat house, with no microphone, and singing beautifully. And I can hear her.”

In most styles of contemporary music, performers sing in so-called straight tones, which is essentially the way all of us sing in the shower. But try to sing that way in a massive opera hall, over a full orchestra, and your voice won’t even make it to the conductor. In order to project to the back of the house, opera singers learn to open up their throats and unleash a big, robust vibrato, the vocal oscillation opera singers make when they hold a note. The first time you hear it, it can seem like a magic trick akin to ventriloquism—how is a person that size producing a sound that big?

“At its most basic, classical singing is freer,” Morris explained. “When we’re singing pop music, we’re imposing some limitations on our throats. One of the first things you notice when you hear classical or opera is that the singer’s voice is free and vibrating almost all of the time.” Morris became fascinated by the challenge of mastering this strange new method, which he describes as “the highest calling for a vocalist, the hardest, the most challenging.” And he wasn’t daunted by the task. “I just thought, I want to try. I want to see what happens and see if I have a voice for this or not.”

Not long after, he returned to Texas, where he enrolled in Southern Methodist University’s graduate music program and won a spot in the Dallas Opera chorus. (Following in his father’s footsteps, he also took a job as a choir director at Prestonwood Baptist Church, in Plano.) He likens himself at that time to an athlete who finally discovered the right sport. “You might be gifted as a basketball or baseball player, but if you’re built like Michael Phelps, you’re going to excel at swimming. I had found my passion.”

Not everyone back in Paris understood Morris’s new obsession. One of his friends continued to insist, despite Morris’s best efforts at persuasion, that Merle Haggard was a better singer than Pavarotti. (“I mean, I get it,” Morris said. “If I’m on a road trip, I’m more likely to listen to Rascal Flatts than Meistersinger.”) Still, it was easier taking a gentle ribbing from his buddies than facing the occasional scorn of opera snobs—members of the “pompous ass persuasion,” as Morris calls them, who “are quick to point out that, ‘If Jethro here can do it, anyone can.’” Rarely does anyone say out loud what the man in Frankfurt did, but Morris remains embarrassed about his monolingualism. His greatest regret, he said, is not studying languages in college. “I made the choice to learn roles, not verbs. So I just have to hope that my singing, acting, and musicianship are good enough to offset some of the looks I get during rehearsal.”

One day earlier this year Morris was in Waco to give a talk to a class of Baylor music students. He had driven up that morning from Houston, where he was performing the title role in yet another Wagner opera, Siegfried, which is considered among the most challenging in the operatic repertoire. Morris is one of only a handful of singers in the world capable of even credibly attempting it. Over a strawberry spinach salad at Mix Cafe—just a few blocks from the apartment he’d rented as an undergraduate—Morris admitted that the role leaves him utterly exhausted. “I couldn’t walk or talk yesterday,” he said. “That’s what five-hour operas do to you. I have to sing over a one-hundred-piece orchestra, and there are moments when every one of them is playing as loudly as they can. It completely destroys me.”

After lunch, Morris drove to campus for his talk. Dressed in silver-colored boots, oxblood chinos, and a black, untucked dress shirt with French cuffs, the powerfully built 53-year-old paced the room, taking questions and dishing out advice in his mellifluous small-town accent. Flashy clothes aside, he could have been giving a sermon back at Paris’s First Baptist Church. When you get to the level of professional opera, Morris told the students, just singing well isn’t enough. “Everybody’s good. Everybody’s talented. Everybody can sing. Some people are really good with languages, some are good actors, some are wonderful colleagues. My role was, I’m going to be the hungriest. I’m going to figure this out. Because I didn’t grow up listening to it. There isn’t an opera house in Paris, Texas—I grew up listening to Mel Tillis and gospel music. I knew I had to work really hard to make this work out.”

Morris, who refers to himself as a “blue-collar opera singer,” tries to overcome his self-doubt by simply outworking everyone else. When he was first cast as Siegfried, back in 2009, he and his wife, Meg Gillentine Morris, a dancer, singer, and actress, had a newborn son. He was going through a dry spell in his career and couldn’t afford to hire a private tutor, so he spent six months teaching himself the part, spending the better part of each day in bed with the baby and a four-hundred-page score.

“I don’t think he’s ever done an easy part.He does not climb hills, he only climbs mountains,” said Patrick Summers, the artistic and music director of the Houston Grand Opera, who has known Morris for almost two decades. “He doesn’t have any interest in the hills.”

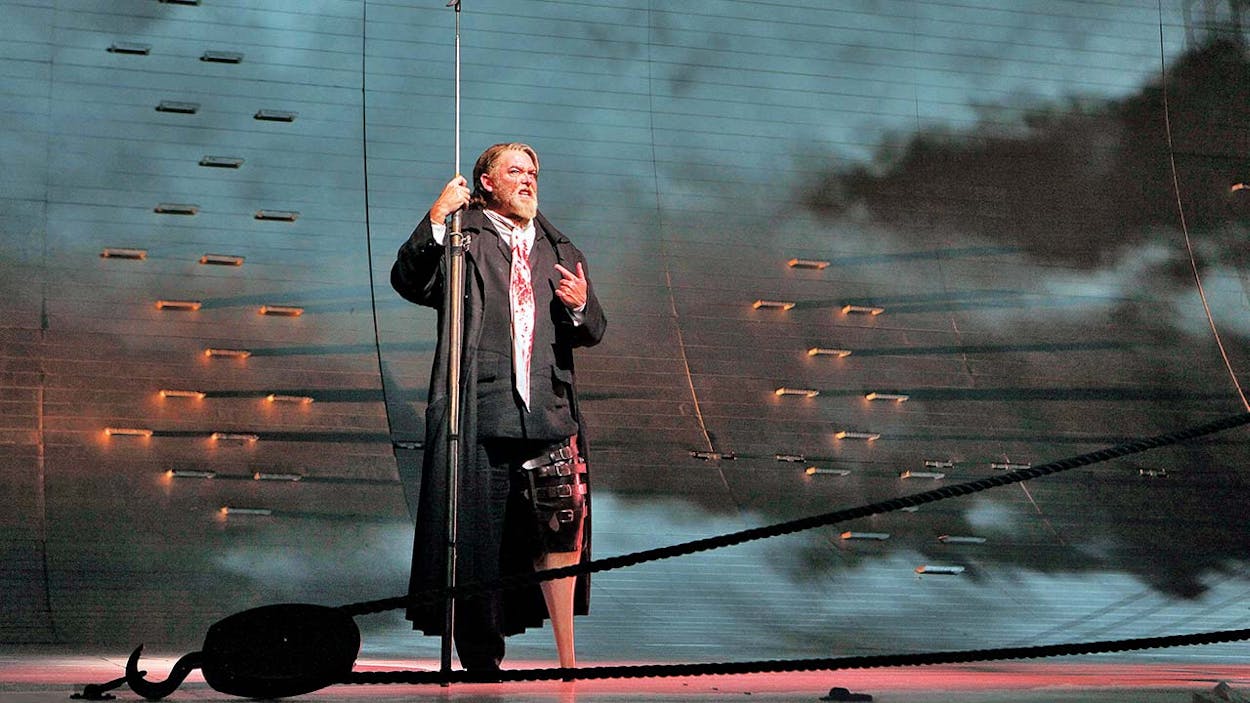

Of all the mountains Morris has climbed, few have been higher than the role of Ahab in American composer Jake Heggie’s contemporary opera Moby-Dick, which opens this month at the Dallas Opera. As usual, Morris threw himself headfirst into preparing for the role, which he first performed in Adelaide, Australia, in 2010. “He would call me every now and then to check on my intention, to check a line,” said Heggie. “Even when we were in rehearsals, he would ask me, ‘Is that the right color [of vocal timbre]? Is that what you’re looking for?’ ” Morris’s perfectionism paid off; his performance won raves from critics and, more importantly, from the opera’s composer: “He found a deeper sense of rage with Ahab and a single-mindedness of purpose that is really clear from the moment he enters. You can tell this is a man on a mission, and he wants one thing.”

The same might be said of Morris. Despite all the critical accolades, Morris remains in constant pursuit of that one perfect vocal performance. There have been glimpses, including one in Frankfurt, during a morning orchestra rehearsal for the same Meistersinger production at which he would later be humiliated backstage. Rehearsals in foreign countries can be frustrating affairs for Morris, since he often can’t understand what the conductor or his castmates are saying. But at this rehearsal, art transcended linguistic barriers.

Morris remembers every detail about that morning, including what he was wearing: blue jeans and tennis shoes. When the company arrived at Wagner’s rhapsodic Act III quintet, “one of the most glorious pieces ever written,” as Morris says, the conductor put down his baton and allowed the singers to set the tempo. Accompanied by the orchestra, they sang uninterrupted for almost fifteen minutes, in an ordinary rehearsal hall, with no audience at all. “When we finished, there was this hush,” Morris said. “We could hear the bows come off the strings, it was so silent. We just sat there, for what seemed like forever. And it was like, this is why we do this.”