Jerry Jeff Walker was known to the world as a first-rate singer, songwriter, and performer. In Texas, the longtime Austinite was also regarded as a generous friend and mentor. (And a prodigious partier.) As Lyle Lovett, one of the most famous recipients of his bigheartedness, told us, “Jerry Jeff helped to introduce so many other songwriters, like Guy Clark, Gary Nunn, Ray Wylie Hubbard, and Michael Murphey. He was a great supporter of his friends.” The list of musicians who were indebted to him reads like a who’s who of two or perhaps three generations of Texas country artists.

To commemorate Jerry Jeff’s death last Friday, we reached out to many of his friends and colleagues to share their memories of him and their thoughts about his life and his influence. Most of them didn’t want to stop talking.

[Note: This is a “rolling” tribute; we will add new entries as they come in. Jimmy Buffett’s remembrance was so good we devoted an entire piece to it. You can read it here.]

Dow Patterson

is an architect and musician from Abilene. He lives in San Antonio.

Sometime in early to mid-March of 1966 I was driving to my first gig at a newly opened Austin club, the 11th Door. I had just turned onto Red River from our apartment on East Seventeenth Street when I spotted a tall skinny guy wearing a narrow-brimmed canvas cowboy hat (with vent grommets around the sweatband), a purple velour turtleneck that zipped up the back of the neck, black skinny jeans and Beatle boots. He was walking at an extremely jaunty pace and carrying a guitar case with a harmonica rack tied on the handle. Because I reasoned that he had to be going to one of several nightspots down that street, I pulled over and asked where he was going. When he told me the 11th Door, I said, “Me too, throw your guitar on top of mine in the back seat.”

At the Door we immediately went to a really tiny triangular room backstage to tune

up. I started doing that, but Jerry Jeff pulled out his guitar and a yellow legal pad—some pages had already been torn off or folded back. He was writing intently and occasionally playing a few chords. He was obviously writing a song.“Okay, I think I captured this guy!” he said. “Wanna hear it?”

“Yeah! Shoot.”

What I heard next was the first performance of a song we all know as “Mr. Bojangles.” Truth!

During that week of our double bill, Jerry Jeff turned 24 (I’d just turned 25). So I invited him over to our apartment for a celebratory dinner. My wife Becky made a big chocolate cake and stuck a huge beeswax candle in the center. When Jerry Jeff left that night we tried to get him to take his cake. All he wanted was that candle.

Robert Earl Keen

is a singer-songwriter from Houston. He lives in Kerrville.

I first heard Jerry Jeff Walker in 1974 when I was a senior in high school. I don’t recall the song, but I remember the morning I heard his voice. I was such a huge fan of top forty country that Jerry Jeff’s sound was almost a shock. It was so unique, I literally sat straight up in my bed and said, “What the hell?” Afterwards, every time a Jerry Jeff song played, I turned it up. The laid-back authenticity of Scamp Walker’s delivery made his sound feel easy and real; his voice has the familiar quality of a long-lost friend.

We never really became friends, though. I’m not exactly sure why, even though we crossed paths more than a time or two. I think I just wanted to stand back and listen to the man sing. That voice and his songs were all I needed to know about Jerry Jeff Walker. His music was what led me to the well-worn bridge that spans the wide chasm from music lover to music maker. For that, I’m eternally grateful to the man and his music.

Lucinda Williams

is a singer-songwriter from Louisiana. She lives in Nashville.

Before I got to Austin, I’d bounced around some. I played guitar and sang in New Orleans for a while, and then the Bay Area for a while. I’d tried college for a couple semesters, but not really. Music and the road were calling.

I landed in Austin in 1974. I was just 21, but as soon as I got there, I could feel it. There was something special in the air, a little like what San Francisco must have been like in the sixties. Some were calling it the cosmic cowboy scene, and others were talking about longhaired rednecks. But whatever it was, Jerry Jeff defined it.

I remember seeing him early on at the Soap Creek Saloon when it was still out on Bee Cave Road. The songs were what got me. “Mr. Bojangles” is just a great song. It told a story, but also had a melody that you couldn’t get out of your head. But his other songs had so much humor, and they were anthems. There was a feeling of “us against them.” The rest of Texas was so conservative, but in Austin, a guy could have long hair, and everybody could smoke pot, and the music grew out of that. It was like, “This is a party, let’s play some music.” And Jerry Jeff was the ringleader.

Years later, I’d always hear him call that period “Austin-before-the-TV-show–Austin City Limits Austin.” It really was a magical time.

But it’s funny. I was playing for tips on the street, down in that little flea market on the Drag, by UT. But if you wanted to play a club, you had to have a band. You had to be like Jerry Jeff and [his band] the Lost Gonzos. Well, I couldn’t do that. But down in Houston, at places like Anderson Fair and Prufrock’s, they wanted to hear the singer-songwriter acoustic thing. So Lyle Lovett would drive down there from College Station to play. And I’d drive down from Austin. And after doing that for a couple years, in 1976, I moved to Houston. So now that I think about it, that may have been Jerry Jeff’s biggest influence on me: making me move to Houston.

Todd Snider

is a singer-songwriter who recorded an album of covers of Jerry Jeff Walker songs. He lives in East Nashville.

Jerry Jeff Walker, the first record he made in Austin on Sixth Street with Michael Martin Murphey’s band, nobody believed that was really a record, because nobody did that at the time—buy a mixing board and rent a building and bring your friends down and get ’em drunk and make a bunch of music. The labels didn’t stand for that. But if you wrote “Bojangles” and you didn’t need their money, they had their hands tied. They couldn’t hold you ransom with tour support, because you already had a nice car.

That’s how that record and ¡Viva Terlingua! were made. Those two records changed the course of country music. There’s no doubt about it. Jerry Jeff Walker was the one Willie and Waylon took note of, because this guy didn’t let the label tell him what to do. And when the label came asking questions, he just pulled his pants down. And Willie was like, “Well, I wrote ‘Crazy.’ I have a car. Why am I listening to the record company? I’m gonna try that.” And he made Shotgun Willie. Then Waylon made his record. And the next thing was Red Headed Stranger. That’s how Austin happened—Willie came home from Nashville and saw some guy [from New York] who had totally invented himself out of whole cloth and decided for himself that he was from Texas. He had printed up his own license to do whatever.

These Texans were just starting to find their hippie roots, and here came this wild New York hippie who’d been doing the hippie thing since it began. And he came to Texas and he was right there for all these kids when they were ready to take the jump. They had a leader. I think Jerry Jeff was the person who got the University of Texas ready for Willie Nelson.

Emmylou Harris

is a country singer originally from Alabama. She lives in Nashville.

I first met Jerry Jeff when he brought his unique brand of gypsy soul to Greenwich Village in 1968. I was a young hopeful singer, an opening act at Gerde’s Folk City, and would make my way between sets to the Bitter End, where he and his sideman, David Bromberg, were regulars. I was hungry for David’s brilliant guitar playing and Jerry Jeff’s inspiring songs. His infectious lust for life and generosity of spirit were inspiring too, creating a kind of family that embraced all of us working the clubs back then and beyond. I’ll always be grateful to Jerry Jeff for those songs, for his joyful noise, and for bringing me into the fold.

Gary P. Nunn

is a singer-songwriter who grew up in Brownfield and a former member of Jerry Jeff’s backing band, the Lost Gonzo Band. He lives in Austin.

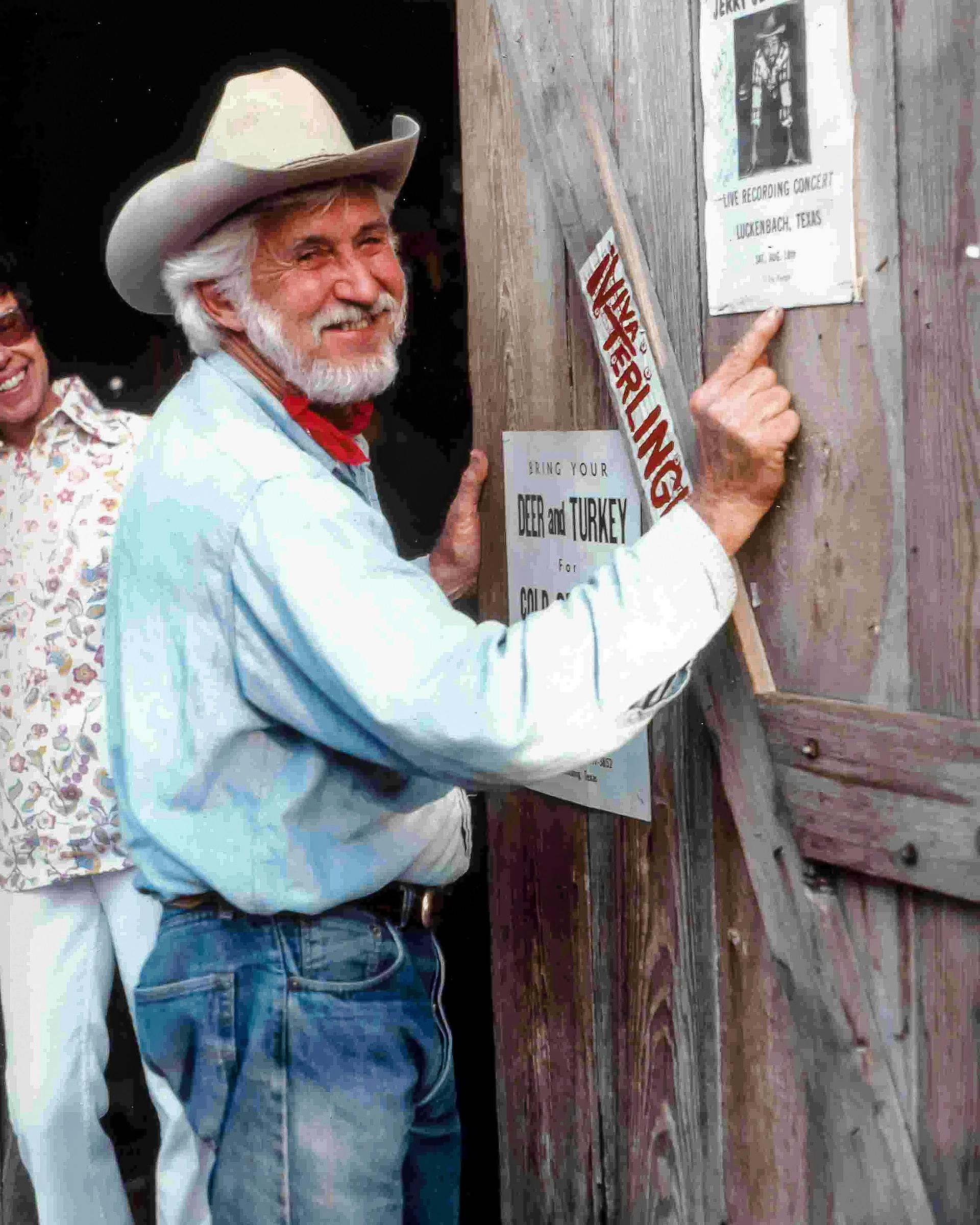

When Jerry Jeff first approached me about recording ¡Viva Terlingua!, we were in the Squeeze-In over on Nineteenth Street [in Austin]. This was right when I had come back from London. Jerry Jeff grabbed me and said, “I found this place down in the Hill Country, and it’s just got a lot of magic about it. And there’s a man down there, Hondo Crouch, and he’s got a lot of magic about him. And I want to go there and make a record. I can’t stand to go back into the studio with producers and engineers and studio musicians, they just don’t have the feel. They don’t have the magic in ’em.” That was the reason we went to Luckenbach in the first place, and he was absolutely right about that.

So we went down there and we set up in the old dance hall. We set hay bales out on the dance floor to baffle what little instruments we had. We’d work from about one or two in the afternoon to midnight. It was just us and a few people hanging around.

The thing about it is, the Lost Gonzo Band guys, we just didn’t know what Jerry Jeff was going to do. And half the time, he didn’t really know what he was going to do. We were kind of just flying from the seat of our pants and Jerry Jeff was just on this magic edge. Gosh, we never went to sleep the whole time we were down there.

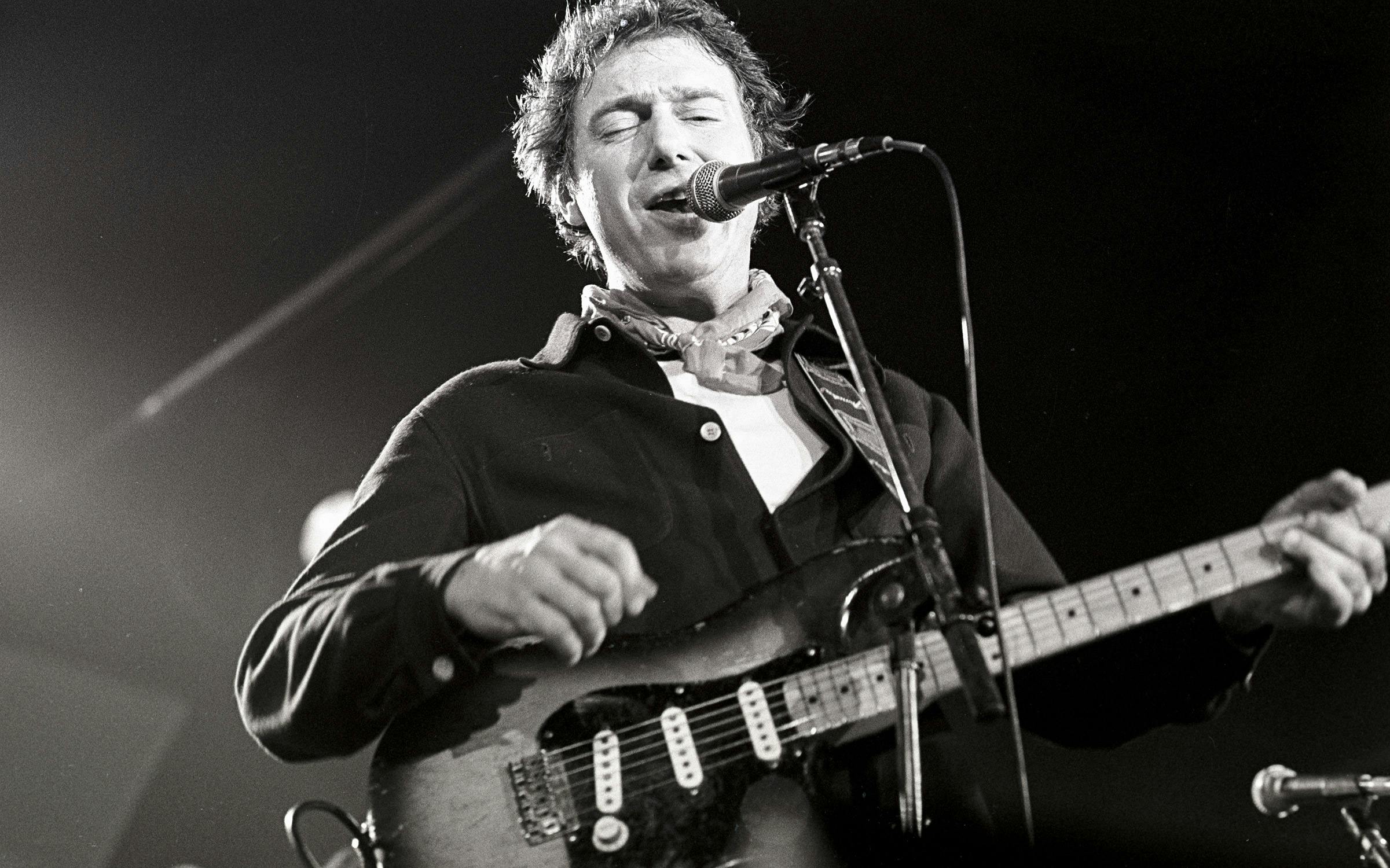

Jerry Jeff’s voice is kind of funky in certain places, but it had that real genuine character about it. And the band was so giving, just surrendered totally to the songs and to the music and to Jerry Jeff, trying to feel what he was doing. And it just worked out. Everybody was right on. Everybody played great. We hardly ever did a recut.

They flew [photographer Jim McGuire] down from Nashville to shoot the scene for the cover. And on the last day or so, they took this picture of that poster that was on the door of the dance hall. And they said, “Oh my god, what are we going to do? This is the picture we want, but it’s got that ¡Viva Terlingua! sticker on it. ” And I was there, and I said, “Call the record ¡Viva Terlingua!” The album had nothing to do with Terlingua. But that name kind of encompassed that whole West Texas, rough and ready, dusty cowboy type of thing.

Becky Crouch Patterson

is a writer and artist and the daughter of the late Hondo Crouch, the “imagineer” who turned the ghost town of Luckenbach into a hub for musicians and creative types from 1971 until his death in 1976. She lives on a ranch near Comfort.

Jerry Jeff and Hondo just fell in love with one another. One time Jerry Jeff was sitting with Hondo out on the patio at our ranch. Daylight was coming up, and Hondo said, “Listen to what I wrote,” and he recited his poem “Luckenbach Daylight.” And it ends very positively, like recognizing God and feeling at peace. And Jerry Jeff said, “I will never be at peace. I will always have the blues.” There was just so much agony and ecstasy in his life. I remember another time Hondo was depressed because his wife had left him. He was laying there naked in bed, and I remember Jerry bringing him coffee and he sat there next to him singing Guy Clark’s “That Old Time Feeling.” The songs always matched whatever mood was around at the time. And that song reminded him of Hondo.

Ray Wylie Hubbard

is a singer-songwriter who grew up in Dallas. He lives in Wimberley.

The thing about Jerry Jeff that stands out to me is that he was a great songwriter but also very gracious to other songwriters. Like on ¡Viva Terlingua!, he put me and Gary Nunn on there, and a couple of Guy Clark songs, before any of us were doing anything.

So the first thing you hear when he plays my song on that record, “Redneck Mother,” is Bob Livingston saying, “This song is by Ray Wylie Hubbard.” Well, the record label wanted that off. They said, “If this gets played on the radio, everybody’s going to think that’s Ray Wylie singing it.” But Jerry said, “Nah, leave it on there.”

So there I am. And to me, ¡Viva Terlingua! is the definitive progressive country, outlaw country, Texas music record. It still holds up. It still influences so many people, and not just because of the songs but because of the attitude. Jerry Jeff was like the Sam Peckinpah of music. He was going to do it his way. I mean, who records in a beer joint in the middle of nowhere called Luckenbach, with hay bales for sound baffles? But that album is still magic today. You can feel it, sense it.

Losing him is gonna hurt for a while. But the legacy is going to be his songwriting, his belief in other songwriters, and his spirit with the way he would do things, his whole cantankerous coolness.

Ramblin’ Jack Elliott

is a folk singer from Brooklyn. He lives in California.

I think the first time I met Jerry Jeff was around 1963 or 1964 at a place in New York City called the Kettle of Fish, which was a bar right next door to the Gaslight Cafe, where Bob Dylan and a few other unknown folk singers got started. I met Johnny Cash in there one day. Jerry Jeff came along with Arlo Guthrie and me to do a radio program somewhere.

[Once, when I was in Austin] I called Jerry Jeff and he invited me to his house out in Oak Hill. So I went out to Oak Hill and I was hanging out with Jerry, and Susan got tired of hearing us telling stories all night. So she says, “Why don’t y’all get in the truck?”

So, we got in his little gray pickup truck—I think it was a 1948 Ford—and drove into town and we went to a place called the Raw Deal. They had a sign that said, “No guitars. Leave ’em in the cars.” And we brought two guitars in and serenaded the waiters. I think we actually managed to play two songs before they kicked us out. At the same time a fire had started up in the kitchen—a frying pan caught on fire. There was a big flame. Well, there was a firehouse right next door to the place and just as they were evicting us and we’re trying to go out the door, the firemen are coming in with a hose. So we had to back up and let them come in. When we finally emerged out the door I looked over to my left and there was a pair of sweethearts sitting up on the shoeshine stand they had out front. They were staring out over the horizon like they were admiring a sunset. But I think they were on acid or something because there wasn’t any sunset. They didn’t even seem to notice the fire engine or the firemen or anything. They were just sort of starry-eyed, looking up at the sky. But I admired that sign that said, “No Guitars. Leave ’em in the cars.”

I think we made it back home, but I don’t know how.

I’ll sure miss Jerry Jeff.

Scott Newton

has been the photographer for Austin City Limits since 1979. He lives in Austin.

In 1972 the Austin music scene was based around two people: Michael Martin Murphey and Jerry Jeff. After “Cosmic Cowboy” became a hit for Murphey, he left Austin. Jerry Jeff’s place—down a long dirt road just south of Austin—was the clubhouse for all the singer-songwriters in Austin: Townes Van Zandt, B.W. Stevenson, Guy Clark, Milton Carroll, the guys in the Lost Gonzo Band. They were the best band in Austin. And Jerry Jeff was the center of everything.

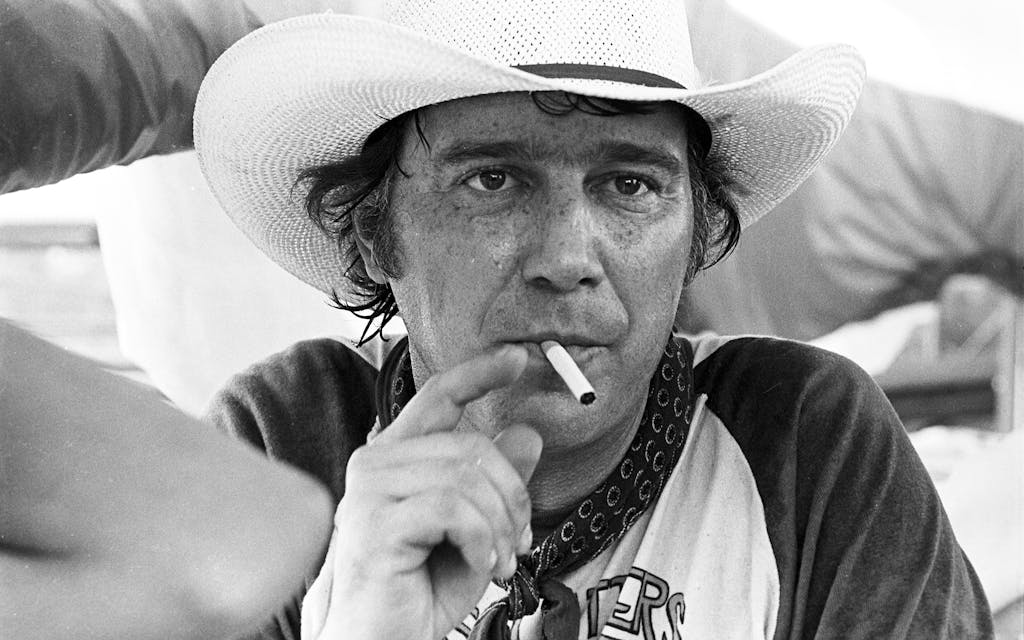

He was one hell of an entertainer. He didn’t have a voice for s–t. He had stage presence and a persona that made you want to watch him. You didn’t know what would happen.

Jerry Jeff was irreverent. He was Scamp Walker. He told stories late at night, passing the guitar. There was never anyone as charming as Jerry Jeff late at night. He was a guy not afraid to do anything. He was a huge good time.

The lyrics of “Gettin’ By”—that’s Jerry Jeff, that’s what he lived by:

Just gettin’ by on gettin’ by’s my stock in trade

Living it day to day

Pickin’ up the pieces wherever they fall

Just letting it roll, letting the high times carry the low

I’m just living my life easy come, easy go

He lived by that until he couldn’t.

He played a lot at Castle Creek, a club across the alley from the Chili Parlor. One night after he played there, a bunch of us stayed up till dawn. Someone had seen a sign out on Highway 290 that said “Walker’s Collectibles” and suggested we go take his picture there. Jerry Jeff was up for it. We were all bleary-eyed, but we got out there not long after the sun came up. It was a foggy morning and I got a great shot. That was my first album cover [1974’s Walker’s Collectibles].

Joe Ely

is a singer-songwriter from Lubbock who lives in Austin.

Early in my career I covered a Butch Hancock song, “Standing at the Big Hotel,” and Jerry Jeff’s bandmate Bob Livingston played it for him when they were recording in Nashville, and he ended up recording it. That set a bond between me and Jerry Jeff. Most musicians in Texas were playing covers from the radio, but we were playing our own songs and songs by our friends. He was a guide in all that.

When you were a close friend of Jerry Jeff’s, you had to wear an armored suit. Every time he’d come to Lubbock, he’d hang out, run around with everyone. If he had a tambourine around his neck, you knew you were in trouble. Every time you saw that, it meant, “Are you saddled up and ready to go?” One time I finished up my set at the Cotton Club and he walked up, had a tambourine around his neck. We went to some small airport nearby, it was 1 or 2 a.m., and we flew to Las Vegas. We only stayed there thirty minutes, he woke up the pilot, said, “This town’s dead, let’s go to Reno.” We went to Reno, hit every casino in town.

Rodney Crowell

is a singer and songwriter from Houston. He lives in Nashville.

I can’t count the people who have told me they came to know about me from listening to Jerry Jeff Walker records. It’s hard to describe the feeling of hearing, for the first time, Jerry’s unmistakable baritone breathe life into a song you’d written. But it can be funny how these things play out.

At the Kerrville Folk Festival in maybe 1977, I was in Guy Clark’s backing band, with Bee Spears on bass, Mickey Raphael on harmonica, and some others. The morning after the gig, Bee put together a rafting trip down either Bandera Creek or the Frio River. Normally I’d be the first in line for something like that, but I stayed at the motel, and I started working on a song that became “The Banks of the Old Bandera,” maybe because I was imagining my friends all floating down a Texas river.

Later in the day they all came back, and Bee came to my room and said, “Hey man, what you been doing?” And I said, “Well, I’ve just written this song.” And he said, “Play it for me.” So I did. And then he said, “Wow. I’m headed off to see Jerry Jeff. I’m going to play him that song.” And I said, “Well, hang on. Let me give you the words.” And he said, “No, I don’t need them.”

So off he went, and he found Jerry Jeff and played him my song. And next thing I know Jerry’s recorded it. I thought, “Oh, my god. How could this be?” And then his record Jerry Jeff came out [in 1978], and I heard it, and I liked it a lot—but it did not resemble at all the song that I’d written, or the version that I’d record later for my album The Houston Kid. But for years people would say to me, “Hey, I first learned about you from Jerry Jeff Walker and ‘The Banks of the Old Bandera.’”

Susan Caldwell

was associate producer of Austin City Limits from 1981 to 2003. She lives in Austin.

Jerry Jeff was always in the moment. Most musicians can’t pull that off, they worry about what was going to happen next. He was not that way. The song “Gettin’ By”—that’s living in the moment. That’s who he was. All joy and music, his buddies, storytelling. Then the scamp would get high and there was a whole other side of him.

He was hilarious, told great stories, could talk about a million subjects, loved to hear people play songs, loved to jump in with them.

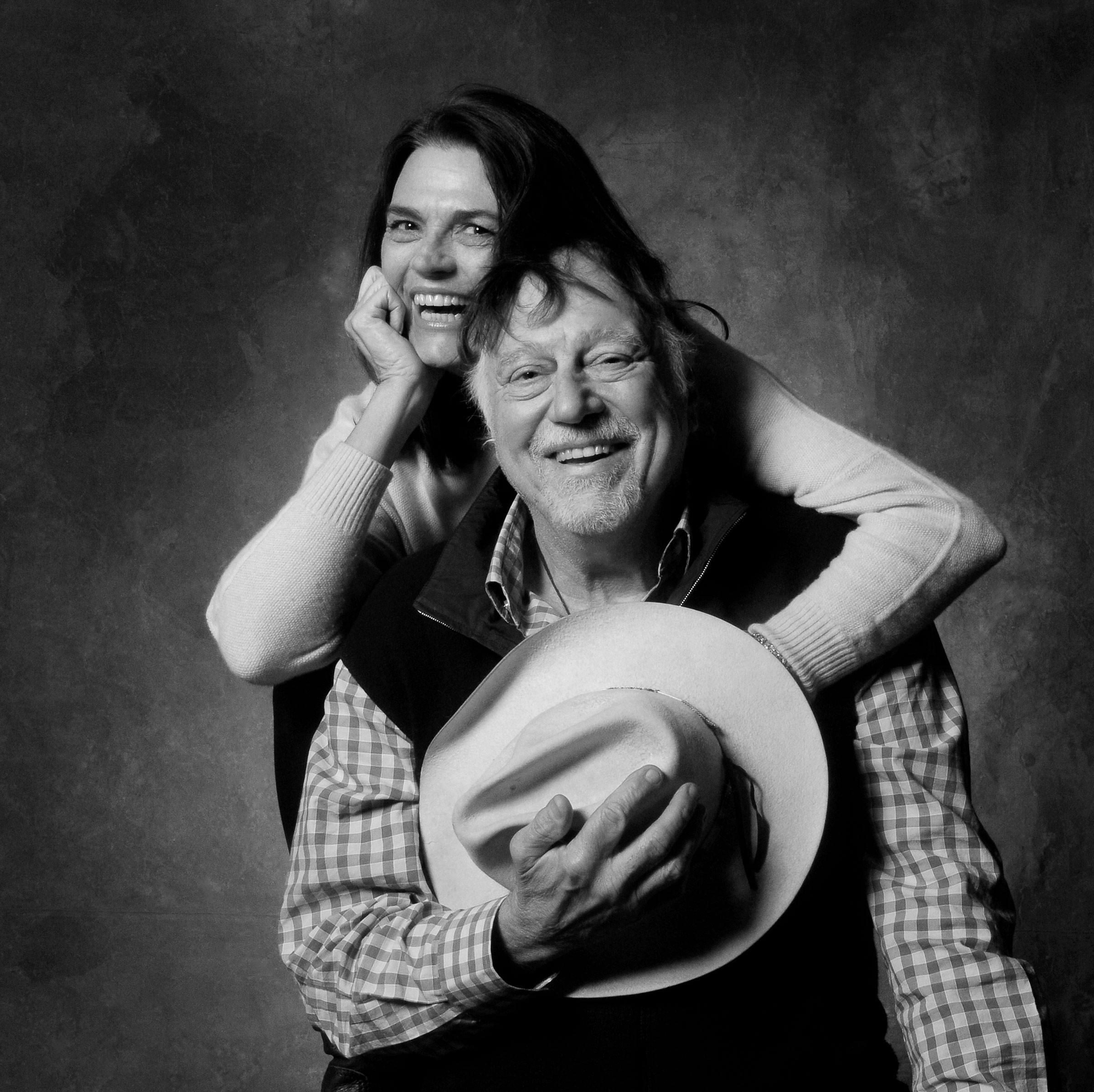

He and [his wife] Susan supported the Austin music community in a straight-ahead way. They were big allies of the Paramount, the Save Our Springs Alliance. They were right there in the middle of everything. Susan is tough. I remember how strong and outspoken she was. There were no women around like Susan—she was very much her own person.

Lyle Lovett

is a singer-songwriter from Klein. He splits his time between Austin and his hometown.

Willie and Jerry Jeff were corner posts for my early appreciation of Texas music, but they were corner posts on diagonal ends of the field from one another. Willie is a Texan. Jerry Jeff adopted Texas and he underscored aspects of Texas, our culture, that people from here too often take for granted. Seeing it from an outsider’s point of view, he had such enthusiasm. He could have lived anywhere and been successful, so we’re lucky he picked Texas and loved it as much as he did.

Jerry Jeff was a deep songwriter. He had a quality that’s so important for artists to have—distinctiveness. You knew it was Jerry Jeff Walker as soon as you heard him sing a note, and his style was so strong that he inhabited every corner of every lyric and every note.

“Mr. Bojangles” is truly a classic and that sort of thing doesn’t happen for most songwriters. In 1976, when I first started playing out, I had to play it almost every set. I sang most of the songs on ¡Viva Terlingua! most nights. He was so instrumental in drawing the blueprint for so many of us.

Early on, Jerry Jeff and Susan came to a gig that I played at the Waterloo Ice House on South Congress before I had any music business going on, really. I remember thinking, “Oh my goodness. There he is!” He wasn’t wearing a hat, so he didn’t look as much like Jerry Jeff as he usually did, but it made me pretty nervous. They sat at a table right in front of the stage, stayed for a couple of sets and he introduced himself and couldn’t have been nicer. I’ve played shows with him over the years since, and Jerry Jeff and Susan have always treated me like I belonged in the room with him. And I always appreciated that. Whenever one of your heroes treats you like you belong there with them, it gives you a real boost of confidence. He did that for so many people, so many generations of musicians. He was kind and generous. He was really a tenderhearted person.

Lee Miller

is the proprietor of Texas Traditions, a boot shop in Austin that was founded by the bootmaker Charlie Dunn, who gained national fame in 1972 when Walker wrote a song about him.

When Charlie would attend Jerry Jeff concerts, Jerry Jeff would ask him to stand up and the crowd would applaud. The song “Charlie Dunn” made him feel flattered. The words that Jerry Jeff wrote are very accurate and paint a clear picture of the way it was.

In 1986, when my wife, Carrlyn, and I bought the shop, Jerry Jeff continued coming in and he’d introduce me to all kinds of people, like Ann Richards and David Crosby.

When Sammy Davis Jr. died, it was in the press that his favorite song of all time was “Mr. Bojangles,” and Jerry Jeff came in and I said, “Hey, I read that Sammy Davis Jr. died.” I told him the story, and he thought that was so cool.

Gibby Haynes

is the Dallas-born front man for Butthole Surfers. He lives in New York City.

Jerry Jeff was a great big part of my high school education. The outlaw scene was huge in my Dallas high school and I remember as an underage teenager trying to sneak into shows to see Jerry Jeff or Kinky Friedman. They called it outlaw, not because they violated the law, but because they went up against the country music establishment. Jerry Jeff was a rebel and what we did later on was definitely influenced by that. Just by naming our band “Butthole Surfers” we dared people to accept us. The outlaw scene and ours had a very similar attitude.

We shared a bill a few times over the years. One time at the Broken Spoke I sat in with Jerry Jeff for “Redneck Mother” and got to do the part of the song that spells out “Mother”—“M is for the mud flaps she gave me for my pickup truck” and so on. I got way too long-winded and self-involved and each one of my letters was like a paragraph. I suspect Jerry Jeff dug it more than the band did. They were not so patiently waiting for me to get to the “R.”

Bruce Robison

is a singer and songwriter from Bandera. He lives in Austin.

When [my brother] Charlie and I were just starting out in Austin, Jerry Jeff and Susan found us and put us in one of Jerry Jeff’s birthday shows at the Paramount Theatre. It’s hard to overstate what that meant to me at the time. Through the years we became friends, though I think he knew I would always be that kid in Bandera clicking his eight-track player back to hear “Pissin’ in the Wind” again and again and again.

As a man, he adored Susan and Django and Jessie. As a songwriter, he wrote “Mr. Bojangles.” As a performer, he connected with a couple works of art in a way that is so rare. I hope folks know how influential he was.

Jack Ingram

is a singer-songwriter from Houston. He lives in Austin.

When my friends were digging into Led Zeppelin IV, Jerry Jeff felt every bit as edgy and rock and roll as Zeppelin did. I was always acutely aware that guys like him, Willie, and Waylon took big chances and that’s the only real requirement for punk rock and rock and roll. You just have to convince yourself and others that you don’t give a f—. That was Jerry Jeff.

When he called, when you go in a room with Jerry Jeff, you’re going to get the full treatment. And you don’t get to turn the volume down on any part of his personality. He would just dive right in. The whole idea of being out of control, seemingly out of control, but always nailing the show? He’s obviously crazy, but he never forgets the lyrics.

He felt dangerous. But he always cared about the song. You know when you see punk bands and the whole act is about exploding onstage and ultimately breaking the drum kit? There was that dangerous edge to Jerry Jeff that really appeals to me. But that kind of thing means nothing to me unless the songs are there. He was like [the great Minneapolis rock band] the Replacements to me. It was that immediate—”Whoa!, This is brilliant, but it might also come unglued. What’s going to happen?”

When I was in high school, listening to ¡Viva Terlingua! on headphones, I remember marveling at the way he made that record. You could hear crickets, and you can hear things that people don’t allow for normally. The atmosphere and the setting were instruments he had no control over. But it made me just climb in. Everything seemed so off the cuff, but not loose or sloppy.

He’s an underrated songwriter because of the success he had with one particular song, “Mr. Bojangles.” He wrote a standard. All the other songs lead to there. He caught lightning in a bottle. And “Mr. Bojangles” is so tight. It tells a story and it makes you cry. It’s bulletproof. A lot of his other songs were much looser and weren’t as technical because so much of what he did was stream of consciousness. That style tends to lead to a career where you have fans who believe in you, they’re not coming for any particular songs. And people believed in Jerry Jeff.

There are certain friends of mine whose company I enjoy because I know that the glimpses they’ll offer into what’s really going on are going to be earned. And you got to sit there and spend the time to figure that out. They’re cats. You can’t just yell at a cat to come eat. They’re not going to do it. But then all of a sudden they’re on your lap. I think a lot of Jerry Jeff’s bravado was a defense mechanism. And the longer you knew him, the more time you spent, the more comfortable he was being vulnerable. A lot of us are wired that way.

He was a character, but not a caricature. He wasn’t a clown. Part of his character, from the beginning, was being outrageous and full tilt. But what’s also always struck me was that he made it all up, he picked it all up on his travels from New York down to Florida, and over to New Orleans. He cherrypicked all these different pieces of what he liked, what moved him. But none of it was scripted. He was a dreamer. He was willing to go all the way. He made every part of his life up and then made it real. For it to become wholly authentic? That’s magic. It’s life as theater. Once you do that, intentionally or not, your whole life becomes performance art at some level. His public life for sure. And even when I was with him privately, it’s not like he changed much.

Jerry Jeff taught me this: If you say out loud that you’re gonna drive off the cliff, and you believe that you’re gonna drive off the cliff, and you know 100 percent that you won’t look back and that you’re not taking your foot off the gas, then you don’t have to actually do it. If you get everybody in the car to beg you to stop, if they think you would have done it, then you get to be the crazy guy who would do anything. Everybody wins: He gets to live fearlessly, and we get to tell the story about how he almost killed us. It’s a win-win.

Dan Rather

is the former anchor of the CBS Evening News. He was raised in Houston and lives in Austin.

I remember Jerry Jeff playing joints in [Greenwich Village] in the late sixties and early seventies, but I didn’t really get to meet him and spend time with him and Susan until sometime in the late eighties. At that point, almost every time he’d come to New York, Susan would let us know he was coming and we’d go and cheer him on, getting drinks and a club sandwich afterward.

One of the things that always impressed me about him was his deep knowledge and appreciation for basketball. It turned out that he was a high school basketball star. If you listen to “Mr. Bojangles,” maybe you don’t get the vibe that this guy was high school basketball star, but somewhere in upstate New York, his team won a state championship and it left an indelible imprint on him. He particularly liked college basketball and every year for the NCAA tournament, he would invite me over to his house. He had kind of a man cave upstairs at his home and he would watch one March Madness game after another. And he could give you six reasons a pick and roll was not working. And he immediately recognized when one team went to a box-and-one or triangle-and-two defense. He was a near professional grade commentator. He was passionate about so many things.

He appreciated Texas culture so much. It’s a cliché, but they say a convert to Catholicism, or any religion, is sometimes more passionate about it than those who were born into it. And that was the case with Jerry Jeff and Texas. It was a late love but, aside from Susan, his first love.

Eileen Gill

worked for Walker’s record label, Tried & True Music, and was his personal chef from 1990 to 1994. She lives in Austin.

In the early nineties, Jerry Jeff was always on some sort of health kick. He was really into inversion boots—he was always hanging upside down. And he found someone who gave him garlic infusions to purify his blood—I swear they would literally hook him up with an IV and put liquid garlic in his blood. When he did this, he would reek of garlic for days—though he would say, “I don’t even smell it.”

One Friday he went to get one of these infusions and the next day we had to fly to Clear Lake City for some county festival gig. He had a small plane to fly to these gigs and everyone on his plane was about to die by the time we landed. He went to play the show and of course he got really sweaty and was literally sweating garlic.

Jerry Jeff always signed merchandise after a show, but the smell was insane and the promoter told us we had to end the signing early because people were really concerned about him. I think they thought he was terrified of vampires.

Sarah Greenwood Stopschinski

worked for Tried & True Music in the early nineties. She lives in Brenham.

In 1993 Jerry Jeff had a gig at Billy Bob’s in Fort Worth, which was always a big show. He did the usual meet and greet for his fans afterward. As we were leaving, he told me to grab some beers for the road, but there weren’t any left. “Grab the halvsies,” he said, “And fill up the halvsies with the other halvsies.” We left with about two six packs worth of opened beer. Back at the lobby of the Sandpiper hotel, we sat around while Jerry Jeff and his band—Bob Livingston, Freddie Krc, John Inmon, Lloyd Maines—played and sang songs. We drank warm beer until a guy walked past with a rolling cooler. Jerry Jeff offered to buy whatever he had in the cooler. The guy left the cooler with us. With cold beer in hand, I asked Jerry Jeff to play “Little Bird.” Bob said, “He won’t play that.” But he did. They played and sang until three. Listening to stories of the good old days with Jerry Jeff and those guys, that was special.

Pat Green

is a singer-songwriter from San Antonio. He lives in Dallas.

I was given my first guitar my senior year in high school by a girl I was dating. And she gave me two cassettes with it—Robert Earl Keen’s No Kinda Dancer and ¡Viva Terlingua! It immediately struck me that there was something so personal and so real about the way Jerry Jeff told the stories. It seemed like every song that Jerry Jeff ever sang was about his life and his experience. I was drawn to that, his willingness to be candid about everything in his life. As a songwriter, I don’t know how to write songs any other way. I can’t tell stories that aren’t mine and I don’t know how to tell stories from somebody else’s perspective. And I wouldn’t want to. Jerry Jeff taught me that.

I sat down yesterday and wrote a song for him, through tears, and it’s called “The Life of the Party.” I don’t know that I’ll ever put it out. It might just be mine. I wanted to be the life of the party. I wanted to be him. He was a free spirit who also did the work. He was a road warrior, there was no stopping him. And he was the party. I don’t want to sound ethereal but it’s about energy. I watched him make every room he stepped in come alive.

He made me feel okay to be me. He never discouraged or disparaged my trite and young music; my young music was just fine with him. He never made me feel small, or young, or lectured me about paying my dues. What came across to me was, “Go get ’em, tiger.” He was the blade. He was the poke. It’s was always, “Go! Go! More! More!” He was always in my corner. And he didn’t have to be nice to me. He didn’t have to do anything for me, but he did. And he did it for Jack Ingram. And he did it for Todd Snider. He was the guy that told us to do it our way and not worry about what other people say about how you’re doing it. He showed us that however you wind up bridging the gaps from coffeehouse to honky-tonks to arenas, that’s your path. And he told us to be proud of it.

He once told me to stop drinking. He was very direct when he wanted to be. I think if Jerry Jeff tells you to stop drinking, you better listen. I know that he loved me and he cared about what happened to me. He had a big capacity for love. It was Jerry Jeff love. It wasn’t always the prettiest thing, but it was real, there was nothing fake about it. He was not a bullsh—er. I’m a bullsh—er. He was not.

Shawn Colvin

is a singer-songwriter from South Dakota. She lives in Austin.

When I first moved to Austin in the mid-nineties, every Christmas, Jerry Jeff would gather a group of twenty or thirty Austin musicians—people like Eliza Gilkyson, Ray Wylie Hubbard, Joe Ely, Jimmie Dale Gilmore—and we’d go caroling to places like Dell Children’s hospital and the Ronald McDonald House. We’d gather at Jerry Jeff’s house in Clarksville and he’d have shuttles that would take us around to the hospitals. Then we’d end up at the Zilker Christmas tree and finish caroling there.

I didn’t get to know him well until I moved to Clarksville about five years ago. I’d always see him at Caffe Medici and sometimes we’d meet for coffee. He’d regale me with stories—he was an outlaw musician, he’d seen everything, done everything, he had stories out the wazoo. And he was always writing songs. He’d sing me a verse or a chorus sitting there at the table. It seemed like all his songs were about Susan—his gratitude to her, his love for her, a love that lasted. He was always writing, always excited about showing me something new that he had just written.

About a year ago we did a gig at the Paramount Theatre—Bruce Robison, Jack Ingram, Joe Ely, me. Jerry Jeff had been sick and had had surgery but he couldn’t wait to play—he needed to play. His voice was gravelly—more gravelly than normal. He was great that night—he was singing better than he was talking. It was a guitar pull, we swapped songs, everyone told stories about him. It was a celebration of him, like, “He’s back!” When it came time for me to do a song, I explained to the audience that I’d only really known him for five years, and that he once said to me, “You met me after I wasn’t an ass—e anymore.” That got a huge laugh. He wasn’t an ass—e when I met him; it must have aged out of him. He was lovable. He was so positive, he was upbeat, hopeful. All he wanted to do was play. He just wanted to get back out there and play.

Bob Livingston

is a singer-songwriter from San Antonio who played in the Lost Gonzo Band and is widely credited with coining the term “cosmic cowboy.” He lives in Austin. (This passage is excerpted from a Facebook update he posted two days after Jerry Jeff’s death.)

Jerry Jeff was ornery. And we got down to it a few times. I mean, really down to it. But we were brothers in a way, so that goes with the territory. I’ve never met a more resilient, roll-with-the-punches grumpy butt. He just went for it, whatever it was. He was a master of the “Vegas Move” whereby you go for a U-turn on a six-lane highway in full traffic. That was Jerry Jeff. That was his life.

Jerry Jeff was a fearless leader who led us down twisty, turny roads fraught with high adventure. Musically, he was all instinct. He called a great set, there was never a set list. Most songs started with him bashing on his guitar. There was never a count-off. Jerry Jeff was the center of it all and his rhythm was right in the pocket. We were young and green, and right from the get-go it was full-tilt. It all seemed somewhat surreal. The audiences loved the music so much. They loved him. And they loved the band. The joints were always sold out whether it was Billy Bob’s Texas, the Palomino, the House of Blues, or Carnegie Hall. And a thousand more.

But he was ornery. Someone would yell out a request and he would cuss them out right on stage. And the audience would laugh and roar. They expected moments like this. He was everybody’s favorite crazy uncle and got away with a lot. He made sure that no one could tell him what to do. At any cost. In the seventies we toured as Jerry Jeff Walker and the Lost Gonzo Band. We were all on a big record label called MCA. In Boston, the label promo guy had set up radio shows and in-store appearances for us to promote the shows. It was going to be great. Jerry Jeff told them them he wasn’t having any of it. “F— ’em” he said. And he didn’t show. Time and time again. But at the concerts to follow, people were hanging from the rafters going bats–t crazy.

In New York City we once played a punk thrash-rock club called Tramps. All the displaced Texans in town turned out to raise hell. Almost two thousand of them. They held aloft their Lone Star longnecks that had been flown in especially for the show high above their heads and sang every word to every song. “The man in the big hat is buying …” It was intense and thrilling. Rocky, the sound man, said it was the loudest band he had ever heard in the club. “But it wasn’t your fault,” he said. “The f-ing people were singing so f-ing loud I couldn’t hear a f-ing thing youse guys were doing. So I kept turning the f-ing PA up, and up, and they would sing even f-ing louder. I couldn’t believe it! It was f-ing madness!” It was hot, sweaty, and loud in that cavern, and I always said that Jerry Jeff was the first punk rocker.

He had a good pretty good work ethic, if you can call it that. He would talk guitars all day and play every day. He’d write a song, usually about Susan, who had saved his life a time or two. He said, “Write a song about your wife. It’ll get you out of a lot of trouble.” He would go jump in Barton Springs and then hit all the music stores in Austin. Make the circuit. Straight Music. Heart of Texas. South Austin Music. Erlewine Guitars. They would see him coming. He would play every guitar in the place. He might buy a rare J-45, play it for a few weeks and sell it for far more than he paid just because he had played it. I told him he should open his own shop, “Scamp’s Guitars.”

He never wanted to sleep. He would stay up for days. He had been awake longer than anyone. Sometimes the band had to be made of rubber to bend and weave with him out to the edge and back. A roller coaster! We had a kick-ass group and would go wherever he wanted. And he appreciated that our driving force might take him to places that he may not have gone otherwise. In a Texas Monthly interview, Jerry Jeff said that Michael Murphey, who we had also played and recorded with, wanted more control of the band and only recorded in world-class studios. Jerry Jeff said he never told us what to play. He said he depended on that.

Our energy mixed with his. We would record in an abandoned dry cleaners, a dance hall, or in his man cave at home. He never wanted anything too organized. He would be finishing a song up to the last second. On ¡Viva Terlingua!, the song “Gettin’ By,” which kicks off the album, had twenty different takes, all with completely different lyrics. All his records had a live good-time feel. Recorded in primitive conditions. He always liked my bass playing. He called it “Neanderthal bass.”

I met him at the Troubadour in Los Angeles in 1970. I had met Murphey a few months before and we had become friends. We heard that Jerry Jeff was in town opening for Linda Ronstadt. Murphey and JJ had been great friends, but I had never met him. Of course I knew about him, had heard “Mr. Bojangles” in Lubbock in about ’67. I didn’t know who was singing at the time but it stopped me in my tracks. When Jerry Jeff walked onstage that night at the Troubadour, I knew this guy was way different. Cowboy hat, a funky velvet jacket, and some loose bell-bottom pants. When he sat down to play, his pants came up to reveal the coolest boots I’d ever seen. I’d later come to know they were made by a boot maker in Austin called Charlie Dunn. He would write about it and tell Charlie’s story dead on.

This is the stuff I want to remember. The high Hill Country rain good-time fun. Never a blue note. Everything up and happening. Leaping and the net sometimes not appearing. And he was all right with that. Now there are three Gonzos who have died in 2020: Riley Osbourne, Kelly Dunn, and Jerry Jeff. That “old time feeling comes sneaking down the hall.”

But as the David Halley song he sang says, “I wish hard living didn’t come so easy to me.” It all caught up to him. He lived hard and played hard. I will miss you Scamp. We all will. Fly safe, Gypsy Songman. Love to Susan, Django, Jessie Jane, and the grandkids.

Sally Wittliff

and her late husband, Bill Wittliff, founded the Wittliff Collections at Texas State University, which is home to Jerry Jeff Walker’s archives. She lives in Austin.

Years ago, probably in the early seventies, the poet Richard Brautigan was in town, so Bill and I had a party for him. Jerry Jeff came, and he was in full Jerry Jeff form. For some reason, he started doing what he called “my jumping jacks” in front of our fireplace. Well, there was no rug there, just our longleaf pine floor, and he had his cowboy boots on. I remember he cracked our floor.

Luckily though, that was the extent of it, because [the writers] Bud Shrake and Gary Cartwright were at the party too. The three of them used to put on an act they called the Flying Punzars. They’d all change into these black tights, black T-shirts, and capes and go through this weird acrobatic routine. I know they burst into Ann and Dave Richards’s bedroom late one night to “perform.” But luckily the Punzars did not make an appearance at our house. There was definitely a heyday when it was dangerous to get too close.

But that was before Jerry Jeff married Susan. Bill and I used to have dinner with them a lot. And Susan was so great for Jerry Jeff. She went on to be his business manager, run his website, sell his merchandise. When they went down to their place in Belize, she’d put together shows for him to play and arrange for his fans to get down. She was his best friend and an incredible source of support.

About ten years ago he quit drinking, and that calmed him down. He was no longer the raucous Jerry Jeff of old. And then for the last few years, he took a great liking to playing dominoes. He and Susan would do that almost every day, just sit there for hours and play game after game of dominoes. It was really sweet.