Featured in the Houston City Guide

Discover the best things to eat, drink, and do in Houston with our expertly curated city guides. Explore the Houston City Guide

From the sixties to the nineties, practically everyone who was anyone in the state’s Democratic politics or civil rights movement could be found, at some point, at the Houston home of architect John S. Chase. It was an exquisitely groovy house, a hub for parties and dealmaking, where people gathered—looking good, feeling good—to try and change the world.

“I remember limos pulling up to their house and wondering who those people were getting out,” says Danielle Wilson, a curator in Houston, whose grandmother lived next door to the Chases. “My observation as a child was of everybody wearing these bold colors and mink coats, and men in hats and long trenches. It was like out of a movie to me.”

It was an optimistic house built by an optimistic man. A true Modernist, Chase, who died in 2012 at the age of 87, was the first licensed Black architect in Texas and was always in pursuit of a better American society. A recently published book, John S. Chase—The Chase Residence (University of Texas Press), has reignited an interest in the architect’s legacy and in how he embraced Modernism, a movement that rejected ostentatious flourishes in favor of function and utility. It makes the case that the home Chase designed for his family on Oakdale Street, a quiet cul-de-sac in Houston’s Riverside Terrace, embodied those ideals and significantly affected the city’s political and architectural history.

The slim volume features new digital drawings of floor plans and cross-sections of the Chase house, both in its original incarnation as a spare, one-story Modernist box and after a sweeping 1968 renovation. The original house was completed in 1959 in the Minimalist style of Ludwig Mies van der Rohe. It was one of the few in the country at the time with an open-air courtyard at its center, accessible through glass doors on three sides. David Heymann, a University of Texas at Austin professor of architecture and the coauthor of The Chase Residence, suggests that the courtyard was an oasis from the outside world, a respite from, as he puts it, “the complex minefield of the public realm” that required “tiresome negotiation” by Chase and his wife, Drucie.

In the mid-sixties, the couple expanded the home to accommodate their growing family, which included their young sons John and Anthony (known as Tony) and daughter Saundria, while also transforming it into a showcase for the parties and political receptions they were increasingly hosting. The 1968 renovation reversed the orientation of the house from an inward-focused box to a more outward-facing structure, with a tall, glass-walled second story—as Heymann describes it, “a beacon” to the world—that glowed like a lantern at night. The courtyard was absorbed into the house, becoming a soaring, double-height atrium featuring an elegant terrazzo floor, spotlighted fountains, a pond filled with fish and water lilies, and huge plants growing directly out of the ground. A cantilevered staircase along one wall incorporated a wide platform halfway up that served as a kind of pulpit from which distinguished visitors could address crowds gathered below. The resulting home was highly unconventional, yet warm and welcoming—think the Brady Bunch house, but fancier and more fun.

Texas state representative Garnet Coleman grew up nearby and often played with the Chase children. “We were French Revival, one of the houses from the thirties,” says Coleman of his family’s home. “My mom worked hard on our house, and she would kill me for saying this, but our house wasn’t cool. The Chases’ house was cool.” That coolness was the result of Chase abandoning the aesthetics of High Modernism in favor of a less rigid style. He broke the rules: the second story was proportionally too tall for the first story; the roofline was decorated with details such as dentil molding, a no-no for Modernist purists; and the central atrium was hardly in keeping with the sparseness and restraint of Minimalist orthodoxy. But as his longtime colleague Robert Morris says, Chase “wasn’t too concerned about architecture critics.” He wanted a fabulous home where his family could live and progressive Texans could gather, and that is what he created.

Only a handful of formal architectural photographs of the Chase house exist, but dozens of snapshots immortalize events held in the atrium. In one, Congressman Mickey Leland poses with Saundria, while future Houston City Council member Eleanor Tinsley and other revelers, dressed in their late-seventies best, mingle in the background. In another, guests gather around a buffet at the dining room table beneath a crystal chandelier—the house’s one traditional element, added during the renovation at Drucie’s request.

Those gatherings were more than just gatherings. “They were pivotal to Black Houston,” says Wilson, who organized a 2018 exhibition on Chase at the Houston Public Library. “People say there were a lot of deals made on the golf course, but a lot of deals were made at Mr. Chase’s house at these parties. People from opposite political parties talking, people from various professions all together.” Harris County commissioner Rodney Ellis says, “I can recall the first time I remember going in the house, summer of 1973. All the people that I wanted to be like and be around were at that house.” Over the years, the Chases hosted many more notable visitors, including Muhammad Ali, Harry Belafonte, Vernon Jordan, Gregory Peck, and Ann Richards.

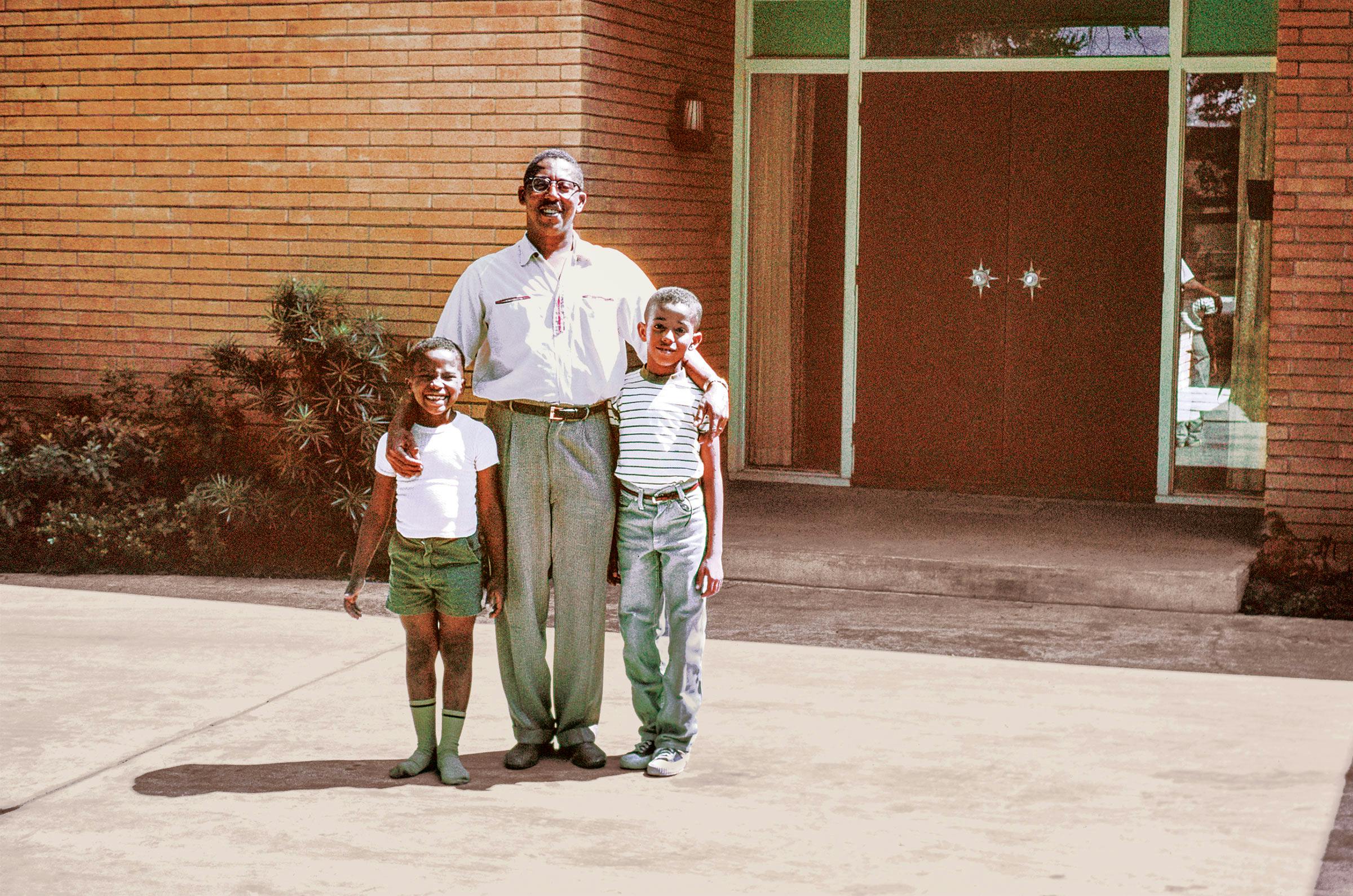

Although the house was designed for entertaining, it was first and foremost the hub of a busy family. For every photograph of a party, there’s a family snapshot: sons John and Tony playing in the driveway; a teenage Saundria next to a white flocked Christmas tree; Drucie on the phone at the breakfast table. Tony says of his childhood, “It was a normal existence in an extraordinary structure.”

Born in 1925 in Annapolis, Maryland, John Saunders Chase Jr. loved to draw buildings and airplanes from an early age. Once, as a young man, he knocked on the door of a local architecture firm and asked the architects what they did. “Even though the members of the firm were white, they took me in and treated me like one of their own,” Chase recalled in a 2008 interview. “They sat me at drafting tables and pulled out rolls of plans to show me.” Later on, a high school teacher who mentored Chase recognized his drive and encouraged him to pursue architecture studies. Chase served in the Army for two years, including combat in the Philippines during World War II, then enrolled at Hampton University, a historically Black university in Virginia, earning a bachelor’s in architecture in 1948.

After graduation, Chase did a brief stint as a draftsman in Philadelphia before moving to Austin to work for the Lott Lumber Company, a Black-owned firm that specialized in building private homes. There were a number of licensed Black architects in Philadelphia, but none were practicing in Texas at the time. “He wondered, ‘Where can I go where I can make a mark?’ ” says Wilson. “And that’s why he came to Texas: because that was a void in the South. He was very aware of that, and there was an opportunity for him.”

Knowing he needed a master’s degree to get ahead, Chase enrolled at UT-Austin’s architecture school in the summer of 1950, just two days after the U.S. Supreme Court decision in Sweatt v. Painter forced UT to integrate its graduate programs. (It would be another six years before Black students could enroll at UT as undergraduates.) Chase and the three other Black grad students attending the university at the time were not allowed to live on campus and were housed together in a tar-paper shack in East Austin.

MID-CENTURY MARVEL

One of the most well-known residences designed by Chase is the Phillips House, built in 1965, a jaunty green-and-white home in East Austin. With its distinctive zigzag folded plate roof and prominent wall of bulbous river rocks, the house is a fixture of mid-century architecture tours.

When Chase graduated, in 1952, things didn’t get easier. In an interview with Austin’s KUT in the late nineties, Chase remembered struggling to find work after he earned his master’s. “There were no Black firms I could go to in Texas, and every [firm] I went to said no. After you do that for several months, and especially when people advertise that they need help, and you get there and you get all these lectures about ‘I’m not like this; I’m from Michigan’ and ‘I’m from New York, but I’ve got clients that wouldn’t—I’ve got white women in the office’ . . . after all that, you get a little fed up,” he recalled. “So I said, ‘I’ll just take this state examination and try my darnedest to pass it, and if I do, I’ll just come on out and hire myself.’ ”

To cut their teeth, most architects initially work for larger firms; an internship is a prerequisite for becoming licensed. But Chase successfully petitioned the Texas Board of Architectural Examiners to waive the internship requirement and, in July 1954, became the first Black architect licensed to practice in the state. (Among other achievements, he later became the first Black architect inducted into the Texas Society of Architects; the first Black president of the Texas Exes, UT’s powerful alumni organization; and the first Black member of the U.S. Commission of Fine Arts, where he helped select Maya Lin’s design for the Vietnam Veterans Memorial, in Washington, D.C.) Chase bore the burden of being many firsts in the face of odds stacked squarely against him. But Darrell Fitzgerald, an Atlanta-based architect who ran Chase’s office for many years, says, “Mr. Chase wasn’t trying to be some trailblazer. He just wanted to be successful and be an architect.”

After receiving his license, Chase founded his own firm. He essentially trained himself, learning on the job how to run a business. He focused his efforts on pursuing commissions available to him, which meant finding Black clients. And in the Black community, there was money in churches.

As a student, Chase had understood that church commissions would be vital to starting his career. His master’s thesis, “Progressive Architecture for the Negro Baptist Church,” contains fascinating architectural details and lays out a complete campus for an imaginary church, including Sunday school classrooms and a “cry room” for babies. He also writes of the role church has historically played in assuaging the “ravaged feelings and aspirations” of African Americans living in the United States. “One of the greatest opportunities found in the church for Negro people,” he argues, “is that they can be recognized as ‘somebody’; this has generated self-esteem and preserved the self-respect of many Negroes who otherwise would have been completely defeated by the physical stresses of life. . . . A woman in the church whose social standing is low is able to take a part in some of the leading church groups. A man who is a waiter and is looked upon as very unimportant on his job, yet has very good standards, can become president of the usher board. Church participation makes these forgotten people feel as if they are of some service to their community.”

Early in his career, Chase and his family would visit multiple churches across the state. “Every Sunday we’d go to a different church, typically in East Texas, because that’s where all the Black people in Texas lived,” says Tony. “And we’d be sweating and the minister would introduce us, and they’d stand up and pass the plate for a building fund.” As a result of his design sensibilities and careful attention to budgets, Chase was offered numerous commissions throughout the fifties and sixties to build churches in Texas. These included First Shiloh Baptist Church, in Houston, and David Chapel Missionary Baptist Church, in Austin, which still stand today. With their angular roofs, plain brick cladding, and Minimalist bell towers, Chase’s churches embrace the democratic ideals of Modernist architecture.

As his career took off, Chase began to take on more commercial and institutional work. The highlight of these commissions is the impressive array of buildings from the sixties and seventies that he designed for Texas Southern University, where he was named consulting architect in 1967. According to Stephen Fox, a historian of Houston architecture who wrote an essay included in The Chase Residence, these buildings reflect Chase at his peak. At the same time as he was renovating his house in Houston, he was experimenting with other architectural styles, notably New Brutalism. He carried this out with remarkable consistency and lightness of touch—especially considering the weightiness of the materials, most typically concrete.

Fox notes in the book that Chase’s firm began to partner with architectural firms for large-scale projects, including the George R. Brown Convention Center, in Houston, in 1987; the renovation of the Astrodome, in 1989; and the Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas, in 1992. None of these big, later designs bear his signature as clearly as his churches or his work for TSU. But they were lucrative, and they enabled him to continue to grow his business. At one point, he had offices in Dallas, Austin, and Washington, D.C., in addition to his Houston headquarters.

The thriving architectural practice Chase built is as important to his legacy as the buildings he designed. “He brought up a generation of Black architects who moved out into the world,” says Heymann. In the seventies, Chase cofounded the National Organization of Minority Architects to help others pursue, as he put it, their “piece of the pie.” And he focused on more than just helping Black architects. In an interview from the mid-seventies, he dubbed his practice “the biggest UN of architects in this town. My secretary is Mexican, I’ve got a man from Nigeria . . . we’ve got three Blacks from Houston, we’ve got a white, and we’ve got [an employee] who is Chinese and born in Hong Kong.”

Chase’s childhood experience of knocking on the door of that Annapolis architecture firm also influenced his decision to maintain his offices in Houston’s Third Ward. “The thing I always wanted to do was serve as an example to young kids, elementary school and high school, who can pass by your building, look up there and see the word ‘architect,’ and come in and ask, ‘What do you do?’ ” he said. “You can’t do that working on the thirtieth floor downtown. And that’s why I have remained in the ’hood. I want the minority kids, the Black kids, to be able to see that there is something else to be done.”

Though he received numerous accolades during his lifetime, Chase is only now starting to gain widespread recognition. Anzilla Gilmore, a Houston architect who cocurated the 2018 exhibition on Chase, remembers being astonished by the details of his life. “When there’s a legend among you, you may not realize it until that person passes away,” she says. “His life inspired me to do more. If I am invited to the party, I’ve got to show up.” And for decades, the party to show up for was at John and Drucie Chase’s remarkable Houston home.

Rainey Knudson is an arts writer in Houston. She recently edited One Thing Well, a book about installation art at the Rice Gallery, to be published in fall 2021.

This article originally appeared in the April 2021 issue of Texas Monthly with the headline “An Extraordinary Structure.” Subscribe today.

- More About:

- Style & Design

- Architecture

- Houston