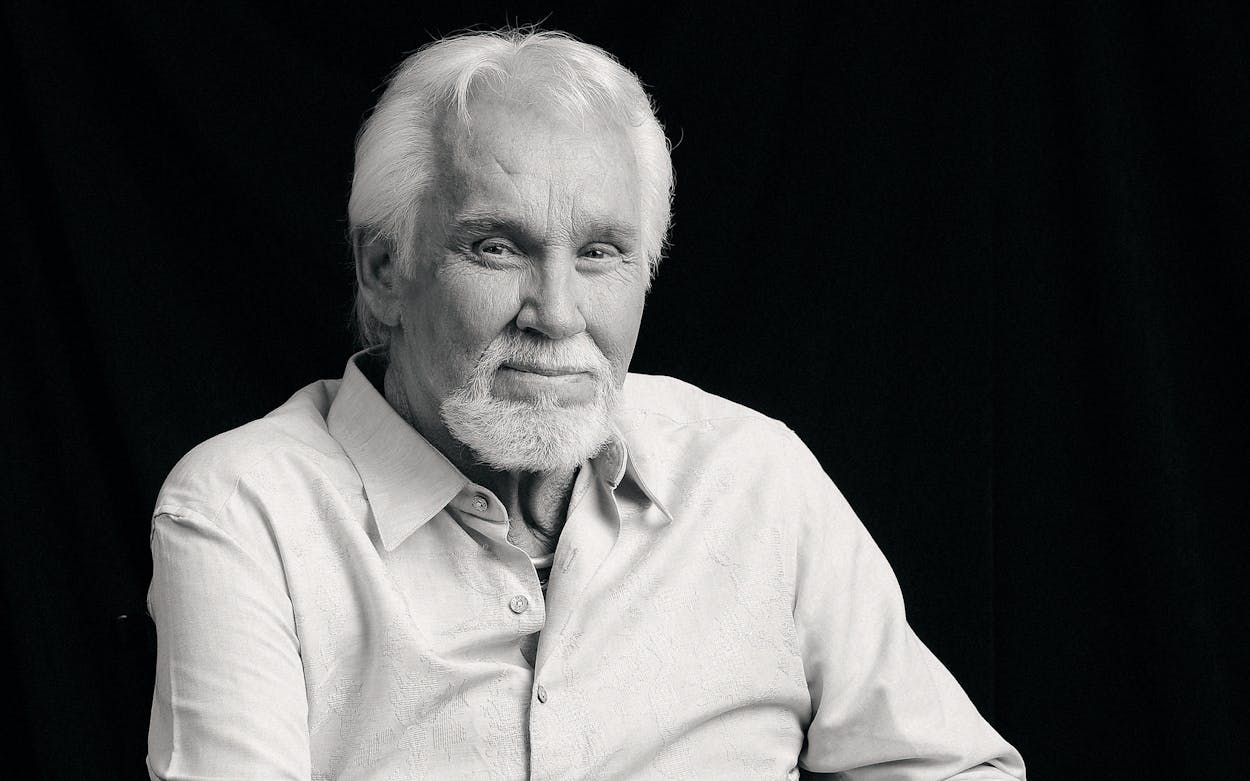

In 2013, Kenny Rogers told Texas Monthly: “I’m a Texan. That’s not something you can ever just set aside.” The country music superstar, who died Friday at age 81, grew up on the outskirts of the Fourth Ward in Houston, an experience that informed his extraordinary 65-year music career. Rogers documented the story of his childhood and the early days of his life in music in 2012’s Luck or Something Like It: A Memoir. A year later, he released what would be his last studio album of new material, You Can’t Make Old Friends. Ahead of that album’s release, I had spoken with Rogers for a piece that ran as part of a New York Times/Texas Monthly collaboration. Here, for the first time, is our full conversation.

Can you draw me a picture of the Houston nightclub scene in the late fifties and early sixties and how you found a place in it?

I was nineteen years old and played mediocre to somewhat good guitar. And I met Bobby Doyle. And he asked me to come and join his jazz group. I said, “I don’t play near well enough to play jazz.” And he said, “I don’t want you to play guitar. I want you to play bass.” And I said, “I don’t play bass at all.” And he said, “I’ll teach you how to play bass. And there’s more demand for bad bass players than for bad guitar players.” I thought was a pretty good logic. So he taught me.

I worked for ten years with him this really avant-garde jazz group, and we worked three different clubs every day. We worked from 5 p.m. to 7 p.m. in what’s called a cocktail job. We worked from 8 p.m. to midnight for what was called a dance club and then worked from 12:30 till 3 a.m. on an after-hours job. So we were very busy and extremely successful. I was making a lot of money when I was nineteen doing those jobs.

Were some of those audiences better than others?

They were three different types of audiences. The first one would have been people sitting around just having a cocktail after dinner or after work. And the second one was dance jobs, where we played music from the 1930s and 1940s and people would get out dancing. There was a lot of smoke in those rooms. It was what you expect from a dance club. And then 12:30 to 3 a.m. was actually an entertainment group where we had all the best entertainers coming in from the Shamrock Hotel and a couple of the clubs around there. You had Tony Bennett and Lorne Greene coming down to see us when they were in town. And people got up to join us on stage. Better bass players that me came in and better piano players than Bobby. But all in all, it was just a fun after hours place to go.

Playing three times a night is where you learned to be an entertainer and not just a musician, right?

The after-hours gig was the real learning experience. We had to entertain them and threw in jokes from time to time. They got great response and we were incredibly successful at that job. We actually owned the club we played, the Act III. Remember, I’m nineteen years old, probably twenty by this time, and we owned the club. But we were only breaking even because the waiters found a way to steal from us. We had no clue.

Could you have stayed in Texas and made a living?

Maybe. But in all honesty, I never wanted to be a solo singer. I always loved singing with groups. Kirby Stone—who had a group called the Kirby Stone Four—loved our group and he used to take us on the road. And so when the Bobby Doyle band broke up, Kirby put out the word and suddenly I’m on a telephone in the lobby of the Houstonaire Hotel, where I was playing a cocktail job. And I sang “Green Green” for one of the New Christy Minstrels on that lobby phone. He kept asking me to sing it louder and I looked like an idiot for the people walking by.

Had I not been in the jazz group, I wouldn’t have gotten to the New Christy Minstrels. And had I not been in the New Christy Minstrels, I wouldn’t have gotten to the First Edition. I would have ever gotten to Nashville [with Larry Butler]. So it’s about being in the right place at the right time. But my mom gave me one of the most incredible pieces of advice you could give anybody on any occupation. She said, “Son, be happy where you are right now. Never be content to be there. But if you’re not happy where you are, you’ll never be happy.” So even when there was nothing was going on, I was happy because I was still playing music at a much smaller scale, but still doing what I wanted to do.

In an odd, only-in-Texas twist, Mickey Newbury ends up being the author of your first giant hit—“Just Dropped In (To See What Condition My Condition Was In)”—and you went to high school with him.

In high school, he wanted to be in our group, but he wasn’t very good. So Mickey goes and buys a guitar and throughout the whole summer, he never comes out of the house. And when he comes out, he was too good for us. But he was a good friend and a talent. “Ruby Don’t Take Your Love To Town” was the first big hit we had and then we had a bunch of other not-as-significant songs like “Something’s Burning,” “Tell It All Brother,” and “Heed the Call.” But “Just Dropped In (To See What Condition My Condition Was In)” was a game changer. It put us in a different category. But the irony of that is he actually played that for me when I was with the New Christy Minstrels and I said, “Boy, I’d love to do that.” And he said, “Well, I can’t give it to you because it’s on hold for Sammy Davis Jr.” Part of me would have like to have heard that.

And you knew Don Henley before we knew who Don Henley was.

I was in the First Edition and we had a lot of friends in Dallas. I ran into Don in a clothing store. And he and the piano player asked me to listen to their group. I said, “I don’t drink and I don’t go to clubs.” They both, in so many words, said, “But we’re really good.” I went and indeed they were. I brought Don out to California just to try to help them. I never thought of trying to make money off them, but he gave me control of his publishing and told me to try to help him. Later he said he had an opportunity to be with a new group but that he’d need his publishing back. I gave it back because it wasn’t my goal to own it in the first place. And that group was the Eagles.

Historically, Texans have seemed to approach Nashville and its music business one of three ways: fully embrace it, rebel against it, or try to change it from the inside. You’ve always struck me as a pioneer of that third choice.

Sure, for better or worse. I’m a country singer with a background in jazz and a lot of other influences. Ray Charles was my hero. I’ve always believed country is the white man’s rhythm-and-blues. It’s where the pain is. Right or wrong, I hit Nashville and did some pop songs. I worked with Lionel Richie and Barry Gibb. But I feel like I drew a lot of people to country music who wouldn’t have gone there without me. Country music couldn’t ever understand that not everybody’s history goes back to Hank Williams. For a lot of people, it starts with Alabama or Dolly. And now it starts with Taylor Swift. That’s healthy for country music. I think I took a lot of flak for taking country pop, but I broadened the audience. Country has always been too country for a lot of people.

Throughout your autobiography and each time we’ve spoken, you’re almost gratuitously good about acknowledging and crediting the people who helped you along the way.

Someone’s told me once that most people who are successful are successful because someone believed in them. And they didn’t want to disappoint that person. So you end up trying harder. And I think that’s what happened. And Kirby Stone really believed in me. There’s no end to what can be accomplished when you don’t worry about who gets credit for it.

As a live draw, is it safe to say the old-school, almost Vegas-like entertainer aspect of what you do is what has carried you through?

I think that’s what separates me. The thing I tell people when I go out onstage is that it’s not important that one person leave here saying, “He’s the best singer I’ve ever heard.” But it is important that every last person leave saying, “I enjoyed that.” I’ve accomplished a lot of that through laughter. I’ve always found people will clap to be nice, but they won’t laugh to be nice. The easiest route is self-deprecation. People love when you can laugh at yourself.

When you look back at your hits, can you identify a common thread? What makes a song something Kenny Rogers should be singing?

There are two different threads. When I look for a ballad, I look for a song that says what every man would like to say and every woman would like to hear. “Through the Years,” “She Believes in Me,” “You Decorated My Life”—they all fall into that category. What man wouldn’t want to say, “Lady, I’m your knight in shining armor and I love you”? And what woman wouldn’t want to hear that? The other common thread was songs with social commentary. “Reuben James” was about a black man who raised a white child. “Ruby, Don’t Take Your Love to Town” was about a Vietnam vet who came home to a wife having an affair. “Coward of the County”—and I’m amazed how many people don’t know this—was actually about a rape. Even “The Gambler”—it’s about a concept of how to live your life, not necessarily about gambling.

Duets have always been a major part of your success. What do you know about singing duets that most people don’t?

You don’t start with an artist. You start with a song and say, “Who could sing this well?” And you have to find a song that when it’s done makes a statement. Singing duets is a lot like running a hundred-yard dash. If you go out and run it as fast as you can, that’s one thing. But when you put someone in the lane next to you that runs a little bit faster, you’re going to run faster. That’s what happens with duets. You go in and someone like Dolly [Parton] really sings and you think, I have to redo my part. And then she redoes her part. And everyone keeps taking it up a notch. That’s what happened here.

This deep into your career, what’s still exciting about having a new record?

My goal is to continue to be relevant, to not live off my credentials. But I can only compete in one of two ways. I can do what everybody else is doing and do it better, which I don’t like my chances at. Or I can do something nobody else is doing and I don’t invite comparison. That’s where I’m at my best. When I did “The Greatest,” about a little kid who plays baseball, no one was doing anything like that. That’s how it got played. Or “Buy Me a Rose.” Nobody was doing anything like that. So that’s what I try to do is find unique pieces of music. And they work either because of my jazz training I can do what most country artists can’t, or by virtue of the fact that I hear something in a song that no one else heard.

You’re at stage in your career where you’re getting lifetime achievement awards. I imagine that as a kid in Houston, you had no expectation any of this could happen.

When I was a kid, there’s always something that represents success to you. When I was a kid in the projects, I’d walk through the richest part in town to get to elementary school. They all had automatic water sprinklers. I thought that was so cool. So when I lived in Athens, Georgia, I built an eighteen-hole golf course at my house and put automatic sprinklers everywhere. I’d sit on a golf cart and watch those sprinklers and remember that feeling when I was a kid.

Now you can afford all the sprinklers you’d ever need.

I like to joke that I have them inside my house now. It’s funny what it is that represents success to someone and how when you get it, if you’re smart, you don’t forget the gnawing inside you.

I don’t take anything for granted. I have a new title for the psychoanalysts—impulsive obsessive. I impulsively get involved with something and then I get obsessed with it. When I started playing tennis, I started playing at 35 and played eight hours a day and ended up with a national ranking because I played at some tournaments. And then I got involved in photography and I’ve done three books. All that stuff is important to the effort that I put out to be hopefully above average. I get compulsive about this stuff. I can’t let it go. You know, if I find out I have any talent in something, I want to see how far I can take it. I’ve never been obsession-free.

Was acting an obsession? You did a bunch of it in the seventies and eighties.

Sure. But I’ve always felt that there are actors and there are people who can act. And I’m not an actor. You give an actor unbelievable dialogue and they can make it believable. You give me believable dialogue and I can keep it believable. There’s a lot of people who can’t do that. But I’ve just become convinced that I’m really good at playing me in different clothes.

I saw you at Bonnaroo recently. What it’s like to be in front of a multigenerational audience and know that so many of these people are seeing you for the first time?

I have to tell you, I’m way out of my comfort zone there. I don’t know that I know how to entertain a new audience. I can sing all the songs and if they know some of them we’re ahead of the game.

On the other hand, it can’t hurt that you have a giant bag of hits to draw from.

I’m pretty well armed when I go up there. My theory about hits is that when an audience hears a new song, they have to work very hard to determine subconsciously if they like the song, if they like the way it’s sung and so on. But with a hit, they don’t have to think. They can just smile and clap and sing along. I play new songs occasionally, but I’m much more comfortable doing hits. I went to see Ray Charles once—and I knew him personally by then—and he didn’t do “Georgia on My Mind.” I felt so cheated. That’s what I went to hear. He was tired of doing it.

I don’t get tired of hits. I just don’t. I’m grateful for them.

This interview has been condensed and edited for clarity.

- More About:

- Music

- Country Music