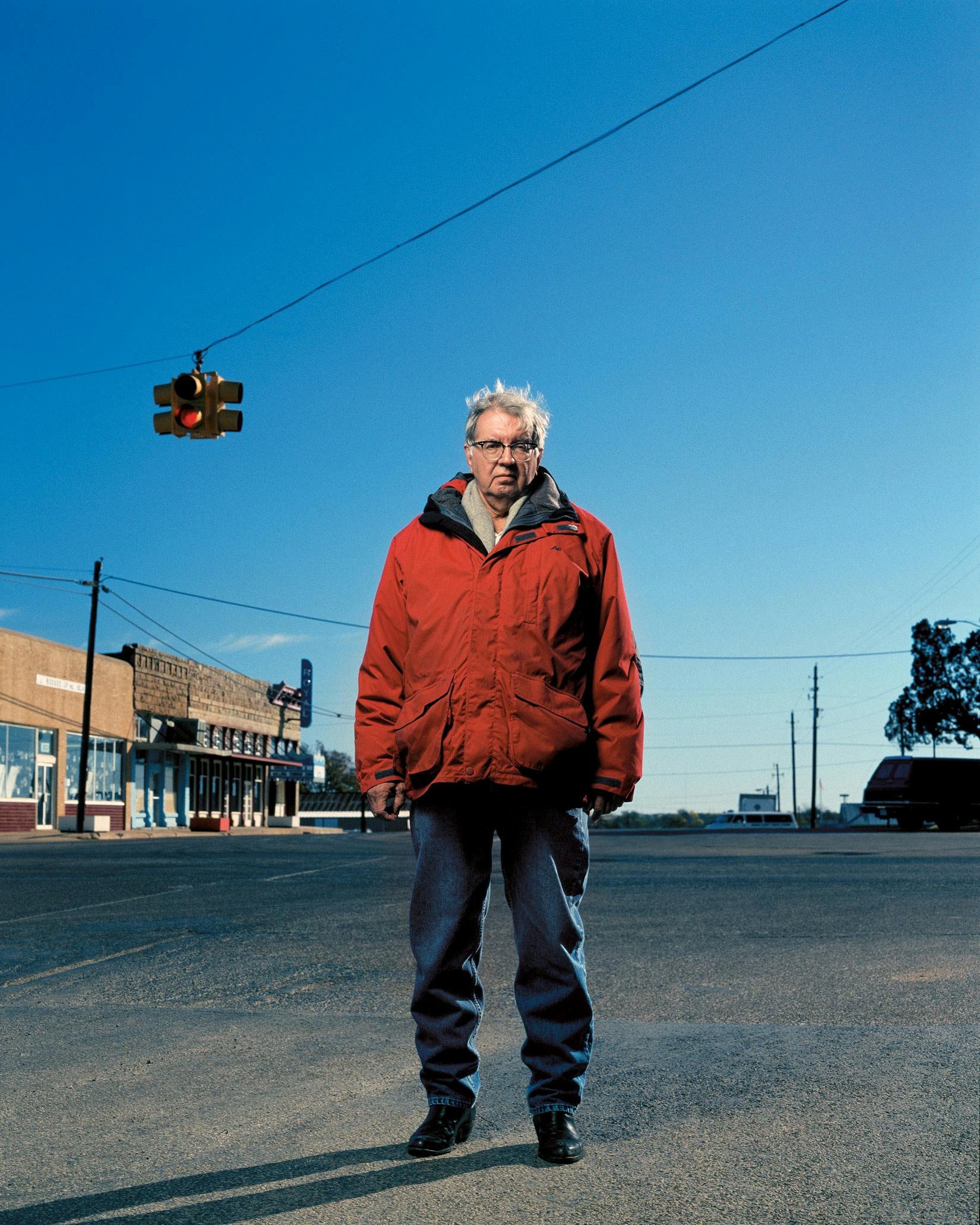

Evan Smith: Here we are in Tucson, Arizona, where you’ve been living since late last year. Let me ask the obvious: Have you left Archer City for good? That’s the rumor.

Larry McMurtry: I should probably start by explaining why I moved back to Archer City in 1997. I’d been living in Santa Monica—we’d produced two miniseries, The Streets of Laredo and Dead Man’s Walk—and a terrible crisis came up at my bookstore, Booked Up. It was a problem with the manager, though it turned out to be not as bad as I thought it was. I had, by that time, nearly 400,000 books in Archer City, and they were not well organized. The business was not set up the way it should have been. I decided that if I was going to stay in the book business and be serious about it, I had to devote a few years to shaping up this bookstore and this book town. That process took six years. We worked and worked and worked—400,000 books is a lot of books. Booked Up is now as well organized as any major secondhand bookshop in America or the world.

ES: During that time I wrote, I believe, six nonfiction books. Another reason for being in Archer City was that it was useful to have access to my personal library of 26,000 books. I could write the biography of Crazy Horse; I could write Walter Benjamin; I could write whatever the six books were without having to go to libraries.

LM: For those two reasons I needed to be in Archer City. Both of those tasks were completed. So I don’t need to be there. Well, I don’t need to be there very much. I need to be there some. And I am there some, about three nights a month.

ES: You haven’t sold your house? That’s another rumor.

LM: Oh, Lord, no. Though a lot of the time I don’t even stay there. I have a wonderful house, but in the windy months I don’t sleep as well. The wind whistles under the door; you feel like you’re in a windstorm. So I stay with my friend Mary down at the Lonesome Dove Inn.

ES: And you have no plans to get out of the book business?

LM: In January I bought the largest library I’ve ever bought: 57,000 books in Pasadena, California. If there had been a moment when I was to leave the book trade, that would have been it. It was a horrible move. It belonged to a lady who had been a dealer but was mainly a collector. She had 27 sheds full of books! And I was not in the greatest of health at the time. I had come to Tucson because there was a freak outbreak of cedar fever. I got very allergic in October, and I had never been allergic before. I had such a powerful reaction to cedar and juniper that I just had to leave. A few weeks later this library came up. It took me maybe a month to get the allergy out of my system. I was not nearly in shape to move 57,000 books. It was such an interesting library that I decided if I didn’t buy it, it meant I’d given up. But I didn’t give up. I bought it. I got friends from Washington, D.C., to come and help me pack it. So I’m very much in the book business.

ES: Okay—how’s business?

LM: The book business is in such terrible shape. It’s paradoxical. Hundred-thousand-dollar books are selling like hotcakes. If you have a $100,000 book, you can sell it tomorrow. A $20 book? Not so easy to sell. A $35 book? Almost impossible to sell.

ES: I guess it’s like the housing market: Million-dollar houses sell better than—

LM: Hundred-thousand-dollar houses. It’s just that way. There are still some high rollers, mostly dot-commers, who are buying expensive books. They had two or three sales this year at Sotheby’s and Christie’s in which stupendous records were set. Books that when I started out as a bookseller forty years ago were standard $200 books—some of Hemingway’s not particularly common ones—now go for $75,000.

ES: And you have a number of those?

LM: I don’t have any of them anymore, because they’ve all been bought. My end of the business is $500 down to about $50. And that’s the problem.

ES: Let’s talk about Archer City. Leaving aside the issues of the bookstore’s management and your nonfiction book projects, your relationship with the town has been famously up-and-down over the years. I wonder if the conclusion of those tasks allowed you to leave a place where you’re not entirely comfortable even in the best of circumstances.

LM: Well, it’s not complicated. You can say it’s because of food. I’ve lived most of my life in Houston, Washington, D.C., Los Angeles, and New York. I’m an urban person. I’m not a natural small-town person. Even if you discount the fact that I have to deal with my family and have to deal with being the focus of too much local attention, there’s nothing to eat. It’s one hundred miles to a good restaurant. There’s one in Fort Worth, the Chop House, right across the street from the Renaissance Worthington. I’d go down, have a good meal, spend the night at the hotel, and go back. That got to seem weird. There was nothing wrong with it, but I wanted to live in a place where I could eat a really good meal every night by myself if I wanted to. A $100 dollar meal. I don’t eat a $100 dollar meal every night, but I’d like the option.

One reason it’s particularly pleasant in Tucson is because I’ve adopted a little Italian restaurant. It’s the best place to eat in the city, and it’s three minutes from my house. I eat there every night—I’m very much a creature of habit. I sit at the same table six nights a week. I’d eat there seven nights, but they’re closed on Sunday.

I really struggle with this problem. I don’t cook. I can grill fish; I can boil an egg; I can do rudimentary cookery. But I’m very social. I like to go out at night. I like to sit in a nice room and look at beautiful women. I don’t want to just sit on my back porch drinking scotch, and there isn’t much more to do in Archer City.

ES: Can you imagine a situation in which you would go back and live there?

LM: I really can’t. I can’t imagine it. If I got crippled I wouldn’t want to be in Archer City. I would want to be here, or I would want to be in L.A. Something might propel me back, but it’s not too likely. I’ve always had three jobs: I’ve been a writer, a screenwriter, and a bookseller. If I reached a point where I didn’t need the first two of those jobs and I just wanted to spend five or six years truly being a bookseller, then that would be the place. But I haven’t reached that point yet.

ES: On the subject of being a writer: I reread a story that Texas Monthly ran in 1997 in which you said, “I’ve written enough fiction.” And the reality is, since 1997 you’ve published quite a bit of fiction. What happened?

LM: If I could not write another word of fiction and make a living, I would. But I can’t. I live off of fiction, mostly. I have a novel coming out this year, Loop Group, and I have one more novel that I owe Simon and Schuster, about an aging gunfighter. I’m getting close to thirty novels in all, I think. That’s a lot of novels. It’s kind of embarrassing. I don’t even offer them to my friends anymore. They all stopped reading at fifteen or twenty. When a new one comes out, I think, “Do I really want to mail this one around?”

ES: What about the screenplay piece of the puzzle? You recently wrote one based on an Annie Proulx story, “Brokeback Mountain,” about two cowboys in a romantic relationship. It’s being shot in Canada, right? How did it come about?

LM: My writing partner, Diana Ossana, read Annie’s great short story “Brokeback Mountain” in the New Yorker and persuaded me to read it. I’m a reluctant reader of short fiction. I’ve never liked reading short stories, and I’ve never written them. But I read it, and I recognized it as a masterpiece about the American West. We thought of it as a great story about doomed love. We didn’t really think of it as gay or not gay. So I wrote Annie and offered her a very modest option, and she entrusted us with it. It’s the easiest script I have ever written. We used every single line in the story, and when that still felt a little short, we added domestic context for both guys. Really, that’s all we did. We left it as much as possible like the story.

ES: How big is the budget?

LM: I think it’s $11 million.

ES: I guess that’s still low-budget by today’s standards.

LM: That’s real low-budget. I think [director] Ang Lee is a little frustrated at the low-budgetness. He’s never had to make a movie that’s not shot where it’s supposed to be happening. It’s set in Wyoming. It’s not set in Alberta. But it’s 30 percent cheaper to shoot in Canada. That’s just a brutal fact of life that hundreds of American movies have to deal with.

ES: You’ve had a pretty long-term relationship with Hollywood—you’ve written maybe seventy screenplays, and at least half a dozen of your books have been made into films. Has it been a good experience overall?

LM: Oh, very good. I’ve been very lucky. Several really good movies have been made: The Last Picture Show, Terms of Endearment, Lonesome Dove. Those films are as good as anybody is likely to get.

ES: Not everybody who writes books that get made into films necessarily thinks, “This is a good thing for me.”

LM: It’s odd. I’ve always been treated extremely nicely by Hollywood. I’ve had only one or two borderline, awkward, or difficult experiences in 42 years. It’s an interesting culture. I’m very comfortable in Los Angeles. I always have been, since my first visit. I also think that from the beginning, I’ve been realistic about Hollywood. Moviemaking is a chancy thing. You’re pulling together a lot of people who haven’t worked together before, and you’re collaborating in a place you don’t know much about. So it’s hit-or-miss. I’ve been lucky that my movies have hit several times.

ES: You don’t feel like you’ve wasted your time when you write a screenplay and nothing ever comes of it?

LM: No, because I got paid. You always get paid.

ES: Do you see the films you’ve written?

LM: I don’t always see them when they come out. I always get around to seeing them sooner or later, but I don’t have an absolutely burning curiosity about them. Strangely enough, if there’s anything I regret about being a screenwriter, it’s that it has kind of killed my interest in movies. I used to be a huge movie buff. It’s professionalized my passion.

ES: Sort of like the chef who can’t bear to cook at home.

LM: That’s right. I can’t remember when I last saw a movie in a theater. It’s been years and years. And when I see a movie at home, it’s often for professional reasons. You’re looking at an actor; you’re looking at an actress; you’re looking at a director. You see a little of it, and that’s it.

ES: What about the movies made from books you’ve written?

LM: I’m perfectly comfortable with that process, but often the movies come out so long after that I’ve forgotten the book. It’s way back in my history. Even Terms of Endearment took eight years. I have one movie that took eighteen, a TV movie called Montana. I never saw it.

ES: Is it true that you didn’t see Lonesome Dove until ten years after it was made?

LM: That was an accident. I was out of the country when it came out. For a while I saw only flashes of it; I didn’t sit down with the whole eight hours. And then, when we were making Streets of Laredo, I watched it straight through. I liked it.

ES: You don’t feel ownership over the material to the point that you’d be desperate to see what somebody else did to your book?

LM: I’ve never felt that. It’s mine when I’m writing it. It’s the world’s when I turn it loose. You’ve got to understand that directors are going to come in and make a contribution, make it somehow theirs. That’s natural.

ES: When The Last Picture Show was being made, did you ever imagine it would be such a critical success—a classic?

LM: Yeah, I thought it was going to be very good. It was a case of a director getting the right material at the right stage in his career. Unfortunately, I traveled with it in South America once. I did Argentina, Uruguay, Chile, and back up to Colombia. And so I was with that movie for 32 showings, and of course I got to where I couldn’t watch it. I had to get so far away that I couldn’t even hear it. I haven’t seen it since.

ES: Tell me about your collaboration with Diana Ossana.

LM: The reason Diana and I became partners—well, I should talk a little about how my heart surgery [in December 1991] changed my operating methods. When you have heart surgery, your heart is physically jumpy for a while. I had a bit of trouble in Washington. I couldn’t stay there because the fire trucks would drive by and my heart would literally start jumping around. I went to Tucson to stay with [writer] Leslie Sokol, and she has parrots and cockatoos. Those cockatoos would have the same effect as the fire trucks. So I stayed instead with Diana and her daughter. I was quite depressed and mainly just sat on the couch and looked at the mountains for a couple of years, but I could still write fiction. I wrote Streets of Laredo and Dead Man’s Walk and Comanche Moon. It was very much as if it were being faxed to me. It didn’t take me long. I would type it out as fast as I could type. And yet I had no connection with it. It was like something somebody else had done or was doing and sending to me. So I got a very good psychiatrist, and I had Prozac and various things.

They now understand that a lot of people have certain mental deficits when they come out of heart surgery because of the heart-lung machine. The heart-lung machine makes this operation possible, but it doesn’t function like a heart or a lung: It doesn’t pump like a heart and it doesn’t oxygenate as easily as a lung. So when you come out of it, you’re sort of scrambled. I could write a letter, but I couldn’t address an envelope. This wore off in about a year. During this time I was writing fiction clickety-click. I got a lot of screenplay offers—I had been doing a lot of script work before the surgery—but I had to turn them down because I knew that while fiction comes out of the viscera, script work comes out of the head. You have to be able to think through a story structurally. And I could not have done that at all. Diana started helping me so I wouldn’t have to turn down too many scripts. And it worked. We were good partners.

ES: You’re working on a nonfiction book about Buffalo Bill.

LM: I’ve always been slightly interested in Buffalo Bill and Annie Oakley, and actually I got real interested in the aspect of their superstardom. They were big international superstars, really the first American superstars. I don’t think there could have been true superstars any earlier in the world of entertainment. You have to have trains that run on time. You have to have press agents that can commission poster art. It all started in the last quarter of the nineteenth century. There were no superstars before that. Cody was probably the most famous man in the world for a long, long time. Buffalo Bill’s Wild West Show is still running at Euro Disney, still packing in those French kids.

ES: How much of that is the cowboy myth? We talk a lot about whether it’s run its course—

LM: It’s not the cowboy myth. Cody was a terrible cowboy. He had a ranch for a while, but he hated it. His myth was a little bit earlier. It was the myth of the prairie scout. He relates in a way to the mountain men, Kit Carson, guides—stuff like that. And Annie Oakley never lived west of Cincinnati.

ES: Then you tell me, since you’ve written so much on the West: Is the cowboy myth dead or alive?

LM: I think we’ve kind of worn the cowboy out. In the twenty-first century, it’s just not us. The cowboy myth was based on a brief experience that lasted one generation only. It’s the image of the horseman. You’ve got to have someone on the horse. The cowboy myth came from that twenty-year period when they had no railroads from South Texas to Montana. As soon as they got railroads, they stopped doing that, because it was slow and cumbersome and not much fun. But that’s where the romance came from.

- More About:

- Books

- Larry McMurtry