The late singer and songwriter Lee Hazlewood loved to tell stories, and some of them were almost certainly true.

Take the one about how he wrote his best-known song. It was 1965, and the then 36-year-old Hazlewood was living in Los Angeles, where he had made his name as a producer and songwriter of hits for the likes of Duane Eddy, Dean Martin, and Dino, Desi & Billy. According to Hazlewood, he had recently been visiting Port Neches, Texas, where he had gone to high school, to spend time with family. He went to a club in nearby Port Arthur called the Golden Cask. There a couple was having an argument, and Hazlewood watched as the woman stood up and yelled: “One of these days these shoes are gonna walk all over you!” before stalking off. The phrase stuck with Hazlewood, and on the plane home he got out a pen and started writing. The result was one of the defining songs of the era, as sung by Nancy Sinatra in 1966: “These Boots Are Made for Walkin’.”

That’s one version of the song’s origins. In 1967 he told an interviewer a completely different version. The song, he explained, came about because he once jokingly told Sinatra, “You’ve got fat knees. We’re going to have to put some boots on you.” Or maybe, as he also claimed, he wrote it as a love song to close a 1965 show at the Tidelands Motor Inn, a famed Houston nightclub, after doing a set that was, as he put it, “a cross between hillbilly and Gregorian chants.”

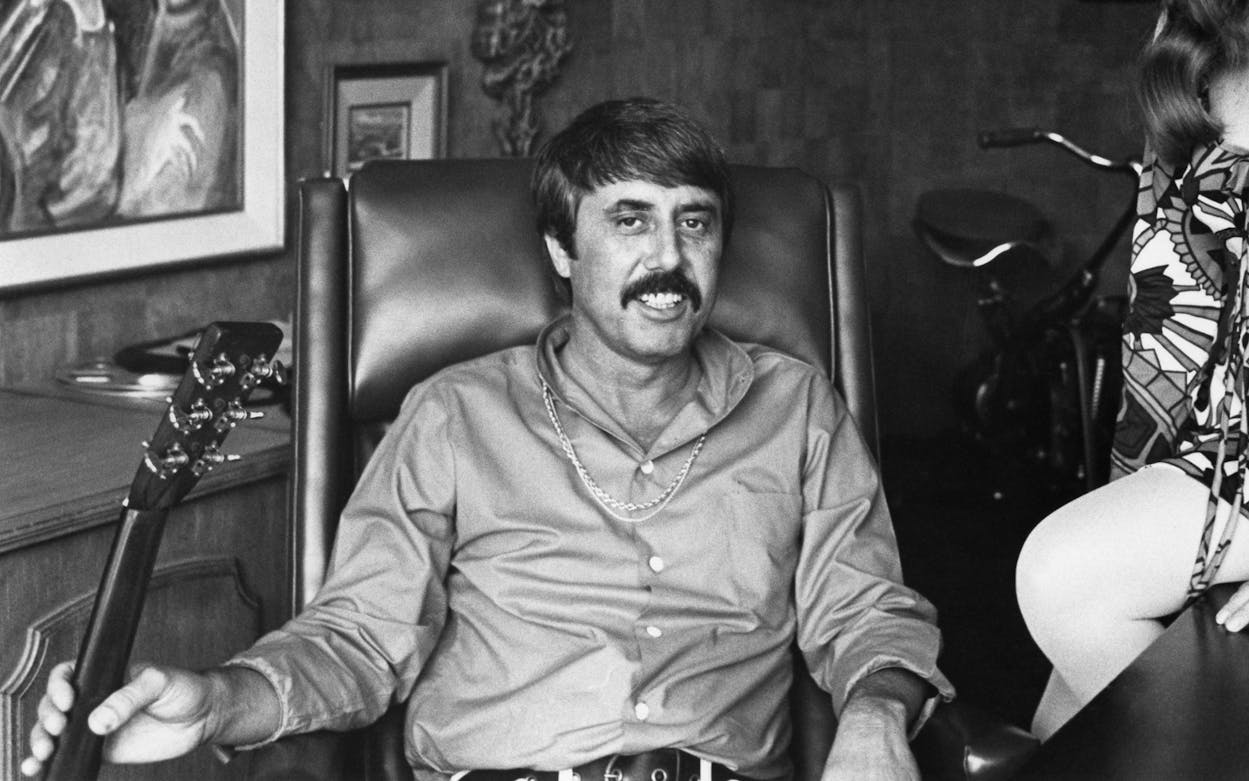

Hazlewood’s refusal to stick to one version of the truth has been a key part of his appeal to three generations of hipsters, Europeans in love with a romanticized version of American culture, and rock stars like Kurt Cobain and Beck. Throughout his life, Hazlewood refused to stick to one version of anything, especially himself. He was a deejay, songwriter, producer, singer, drummer, and guitarist. He was a ladies’ man as well as a rambling man, a cantankerous iconoclast known for a baritone voice and a droopy mustache. He was an opportunist, feeling his way through the music industry at a time when it was becoming a big business, as well as a poet.

He penned a stunning collection of strange, haunting, funny songs that somehow sounded both innocent and experienced at the same time. You’d hear one that was so achingly beautiful you would have to stop what you were doing and listen again—and then you’d hear another that was so corny you would have to stop listening altogether. He wrote mainstream hits about cryptic sex, summer wine, and LSD, and recorded duets with Sinatra that are among the greatest ever sung. He made dozens of albums and millions of dollars, and casually laid the groundwork for some of the coolest sounds of the sixties and then retired from the music business—and then came back and retired again, and then again.

Hazlewood obstinately did everything the way he wanted to, and by the time he died in 2007 at age 78, he was a cult star. And even after his death he lives on. Over the past seven years the influential archival record label Light in the Attic has reissued a dozen of his albums. The latest, 400 Miles From LA: 1955-1956, was released last week; those nascent songs track his time living in Arizona and trying to get his career off the ground.

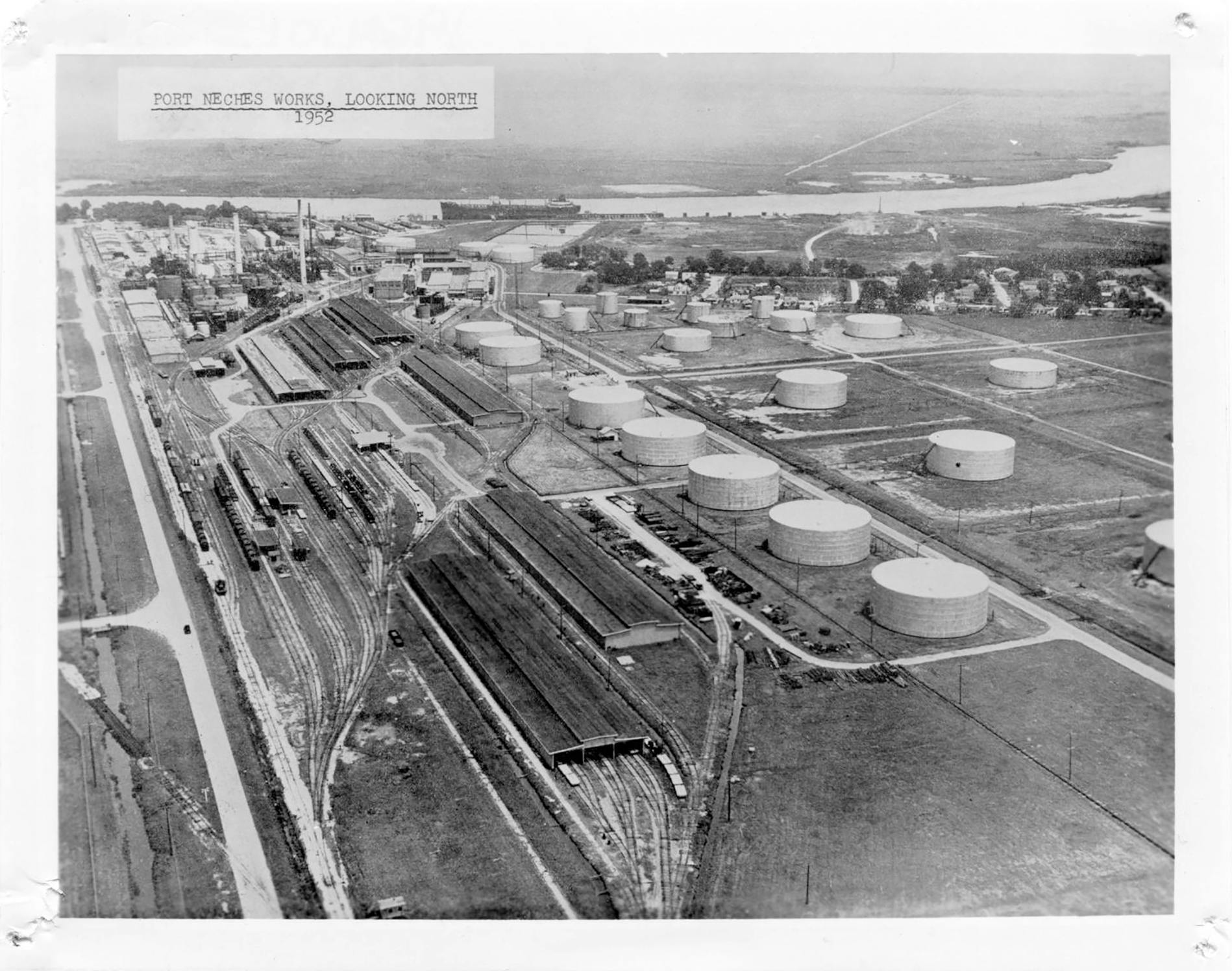

Maybe the oddest and most obstinate thing Hazlewood did—even as he lived the glamorous sixties pop life and then later an extended vagabond existence, moving from state to state and country to country—was to keep returning to Port Neches. The little city in the middle of the Golden Triangle was one of the least attractive places he had ever known, an old-fashioned, conservative place that was the headquarters of Texas’s petrochemical industry. But it was there that Hazlewood felt most at home, in the land that shaped his singular, abiding vision of who he was and what kind of music he could make.

Barton Lee Hazlewood was born on July 9, 1929, at the beginning of the Great Depression, in tiny Mannford, Oklahoma, an oil and gas town twenty miles west of Tulsa. His father, Gabe, was a wildcatter. The family lived near the railroad tracks and young Barton would sit and watch the trains go by. Homeless people often knocked on the door asking for food, and Barton’s mother, Eva, who was half Creek Indian, made them plates of beans and bread. Barton loved hanging out with them. He had a bad stutter, and one of the Hazlewoods’ transient guests helped him cure it, telling him to whistle every time he was about to speak. Mostly, Barton loved hearing their stories.

Gabe was a hard-drinking man with a deep voice and a love of books. He was strict—he whipped Barton with a strap for lying—but also had his doting side; he often took the boy fishing and told him stories. When Barton asked his father if a story was true, Gabe responded, “That’s not important. Good stories need to be told”—something the boy clearly took to heart.

Barton revered his father, who would take him out to the oil wells. As he’d watch his father supervise the working men, he waited for his favorite moment: when one of them threw the nitroglycerine into the well. “They’d put the nitro in the ground,” he said later, “and the ground started to shake–it felt like the end of the world, and up through this hole would come gallons and gallons of oil, screaming through the top of the derrick.” Afterward the men would stand around congratulating each other, chewing on tobacco, and sipping bootleg whiskey.

He heard a variety of music around the house and outside of it. “I grew up kind of all mixed up,” he once said, talking about music. Eva loved pop—Frank Sinatra, Bing Crosby, Perry Como—while his father was partial to bluegrass and country. Gabe also occasionally booked bands to play at local clubs and dances. He got to know Bob Wills, who had moved to nearby Tulsa, and took Barton to see the father of western swing play live. Once, he told his son, Wills had draped him around his neck and shoulders as he played his fiddle and walked around the dance hall. To no one’s surprise, when Barton bought his first record, it was a country-bluegrass classic: Roy Acuff’s “Wreck on the Highway.”

As a wildcatter Gabe had to follow work opportunities wherever they arose, and he moved Eva, Barton, and Barton’s sister, Sara (born in 1935), to a series of small towns, including McLean, Texas, and Fort Smith and Paris in Arkansas. They lived like gypsies, Hazlewood would later say, and those nomadic ways never left him.

In 1943, when Barton was fourteen, Gabe ended the wandering by taking his family to Port Neches, a small town of 2,500 in the middle of the Golden Triangle, the Gulf Coast region bounded by Beaumont, Port Arthur, and Orange that had long been the grimy heart of Texas’s bustling petrochemical industry.

The Hazlewoods arrived in the middle of World War II, and Port Neches was booming. There were refineries, storage tanks, and factories, as well as a brand-new synthetic rubber complex near Port Neches High School. At night the skies glowed orange from the refinery flares while the air smelled like decaying cabbage and rotten eggs. Locals had an optimistic way of coping with the stench. “Smells like money!” they would exclaim.

Gabe didn’t mind any of that. He finally had a stable job, working as a pipe fitter with Jefferson Chemical Company. The Hazlewoods moved into a house on Jefferson Drive, close to the Gulf of Mexico and less than a mile from the home where a little girl named Janis Joplin had just been born.

Barton was a smart, chatty teen, though he would sometimes fall into melancholy. “Such moods would haunt him all his life,” wrote journalist Wyndham Wallace in his 2015 book, Lee, Myself & I: Inside the Very Special World of Lee Hazlewood. Still, he had no problem making friends at Port Neches High School. He and two other teens, Justus McQueen and Jake Derrick, bought a decrepit Model T and fixed it up, turning it into a convertible by cutting off the roof. They painted it blue with bright yellow polka dots and erected a beach umbrella in the center. “We called it ‘The Spotted Ass,’” says McQueen, who would later move to Hollywood and, under the name L. Q. Jones, become a ubiquitous character actor on sixties and seventies cop shows and westerns. The boys took turns slowly driving the car around town or over the bridge to Orange, where locals would stop what they were doing and stare.

Barton already liked to write—he became sports editor at the Pow Wow newspaper and photo editor for the War Whoop yearbook. He liked to read, too, and located an English version of Karl Marx’s Das Kapital—not an easy thing to do in a small town in Texas in the mid-forties. But he wasn’t a bookworm. He would take girlfriends to the Jefferson Theater downtown, then they’d drink Cokes and listen to the jukebox at the Port Neches Pharmacy. His senior year he began dating Naomi Shackleford, who bore a resemblance to Vivien Leigh and was voted Most Beautiful girl in the class of ’47.

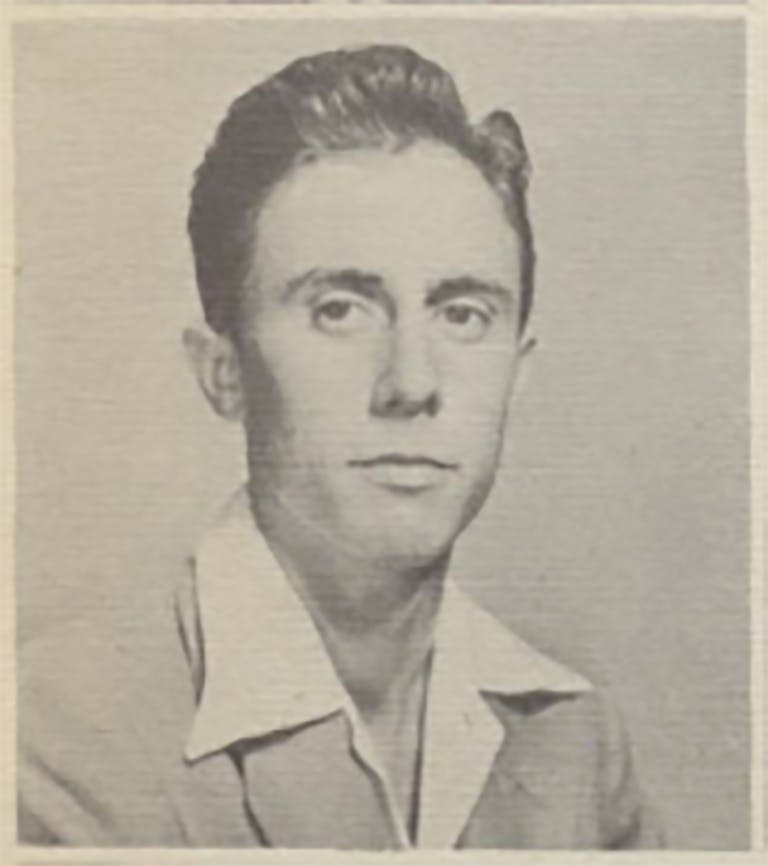

In his senior yearbook photo Barton looks like a man, not a kid—hair slicked back, deadpan eyes, and (unlike most of his peers) no smile. All the graduates provided quotes to run next to their photos. Barton quoted Shakespeare: “Let the world slip; we shall never be younger.” Even at seventeen, Barton was thinking about the loss of innocence and the degradations of experience. “He had a different outlook,” his friend Elton Jones says. “He was always questioning things. Like in civics class, he had a lot of questions.” Barton the oddball intellect also had a dry wit. “He was a funny guy,” says Billy Heisler, his lab partner in chemistry. “He was always popping jokes.”

And he loved music—listening to it, singing it, and playing it. Barton was initially intimidated by classical music until a high school teacher broke it down for him. “He made it as simple as it can be,” Barton said years later. He enjoyed the soft jazz of pianist Eddie Duchin, who sometimes played the melody of a piece with his left hand.

Barton began singing in earnest when he formed, with L. Q. Jones and Derrick, a vocal and comedy group that played around town at churches and community centers. Most of the songs were barbershop quartet tunes like “Yes Sir, That’s My Baby” and “Shine On, Harvest Moon.” Since they were a trio, Barton would rearrange the songs—adapting the harmonies, adjusting the parts—and make them new. “Barton was so clever in how he would take an old song and rearrange it,” says Jones. “He enjoyed it. And he realized he was good at it. We had music nobody else had.” The boys were all good singers but would also tell jokes and do skits. They became so accomplished that the minister at First United Methodist Church, where all three were members, would take the boys around the eastern part of the state to play at church camps. “We were a good group,” says Jones. “We were big hams.” Jones recalls that Barton was self-effacing about his abilities. “To him it was like he found another pocket in his pants and there was some talent in it,” Jones says. “He would make jokes about it, slough it off. He always had some excuse for what he did.”

Barton fell in with another group of friends who played and listened to big band jazz, the teenaged music of the day. They started a band that played at the high school, with Barton on the drums. “We were a dance band,” says Patti Strickel Harrison, who played saxophone. “We were basically a garage band that did standards by people like Glenn Miller. We thought we were hot stuff.”

On a given night, Barton and his friends would head to the local teen dance hall, where the jukebox played Tommy Dorsey, Ella Fitzgerald, Benny Goodman, and Harry James, or hear bands in honky-tonk clubs like the Black Cat, or cross the drawbridge to go to the Pleasure Pier Ballroom in Port Arthur. “Music was our world,” says Harrison. “There was nothing else to do, it was our entertainment. It made up a great part of our lives—it was important.”

With his father’s permission, Barton would go to a nearby blues club to hear touring artists like B.B. King. The Golden Triangle had plenty of blues musicians—and also Creole, Cajun, and country players, men and women drawn to the area looking for jobs in the petrochemical business who brought along their accordions, guitars, and fiddles. The area became known for the way musicians mixed up and melded their styles. Clifton Chenier, originally from Louisiana, moved to Port Arthur in 1947 and was playing blues and R&B along with Creole music decades before he was crowned the King of Zydeco. Gatemouth Brown, five years older than Hazlewood, had grown up near Orange, playing fiddle in Cajun bands and drums in swing bands before finding fame as a blues guitarist. Living in the Golden Triangle, it was impossible to escape the mingling of musical tastes—especially for a curious kid like Barton, who was already “all mixed up.”

Like many of the other ambitious young people around him, Barton wanted to get away from Port Neches as soon as possible; he found the town’s conservative religious ethos oppressive. “Anything that was fun had to be automatically sinful,” he said later. “I can think of nothing we did that was a pleasure that they didn’t say, ‘You shouldn’t do that.’” At the time Barton wasn’t thinking of a career in music. He wanted to be a doctor, and began taking premed classes at Lon Morris College, a private two-year Methodist institution in Jacksonville, Texas.

Unfortunately, the Cold War was heating up, and before Barton could finish his first year, he was drafted and sent to Camp Hood in Killeen as a member of the 2nd Armored Division, General George Patton’s famed Hell on Wheels unit from World War II. He joined the division’s military band as a drummer and spent the next eighteen months in Killeen.

When his stint was over in 1949, he returned to Port Neches and he and Naomi married. But the next year war broke out in Korea, and Barton was called back up and sent overseas. He joined Special Services, served in the Armed Forces Radio Service for eight months and spent time at the front lines. He later told Wallace that the war taught him two things: how to run and how to cry. “Whatever he saw deeply traumatized him,” Wallace says.

But Barton had found his calling: He loved being on the radio, spinning records, and entertaining people. Back in Port Neches, he told Naomi he wanted to be a professional broadcaster, so they moved to Pasadena, California, where he used the GI Bill to attend broadcasting school. Upon graduation, he got a job at a KCKY, an AM pop music station in Coolidge, Arizona. He was now going by his middle name, calling himself Lee Hazlewood.

The early fifties were the beginning of a new age in radio, when people spinning records dropped their traditional anonymity and became celebrities in their own right. Rock and roll radio pioneers Alan Freed and Casey Kasem started their careers at the same time Lee did (each had also learned to deejay in the Army) and transformed the airwaves by playing R&B records by African American artists. Lee began doing the same thing on KCKY, slipping Hank Ballard records between Como and Crosby songs. He also began creating his own on-air characters, such as Eb X. Preston, an old country codger he imagined in the mold of forties movie star Gabby Hayes. Like his father, Lee loved telling stories, and he would pre-record Preston’s half of a conversation and then play it back on air while he responded in real time. Listeners were convinced they were hearing two people having an actual conversation.

Given his love of music, it was only natural that Lee would gravitate towards a new level of storytelling: writing songs. He wrote dozens of them, setting them down on tape, just him and his guitar, with a lot of reverb, which he loved. The melodies were simple and sweet, lonesome and bluesy. He wrote the brooding “Fort Worth” (which he pronounced “Foat Worth”), the rockabilly “I Guess It’s Love,” and a ballad called “The Old Man and His Guitar,” in which an old man looks back wistfully at his life. “Remembering loves,” sang Lee, all of 25 years old, “remembering springs, so many loves, so many springs.”

Many of his songs were about the characters in an odd little town called Trouble. “You won’t find it on any map,” he said in one of the many spoken-word introductions he put on a demo tape, “but you can take three steps in any direction and you’re there.” The characters were storytellers and thieves, good and bad people, young ones and prudish old timers. “Trouble,” he said, his voice soaked in lonesome reverb, “like any other little town, has its share of people who are always judging young people.” Their lives sounded a lot like the people in the towns Lee had grown up in. (These early tapes, much of which was previously unheard by the public, make up last week’s release of 400 Miles From LA.)

Lee was determined to break into the music business, and he would hop on a Greyhound bus and take tapes of the songs from Coolidge to L.A., knocking on the doors of publishers and record label presidents and trying to interest them. He was rejected time and again. He also began writing songs for local artists—and even going into the studio and producing them. After penning and producing “The Fool,” which became a hit for a local singer, Lee was offered a job as a producer at Dot Records in L.A. in 1957. By then he and Naomi had two toddlers, Debbie and Mark, and the family moved to California.

For the next decade, the singer, storyteller, and arranger from Port Neches would have an oversized effect on American popular music. From the start, Lee had a vision for how he wanted everything to sound: spare and lonesome. He had been working in Arizona with a teenaged guitarist named Duane Eddy, and Lee traveled back to Phoenix to produce and write songs for him. Lee pushed Eddy—a country player in the mold of Chet Atkins—to play simple melodies on the lower strings, like Eddie Duchin had done on the piano. But Lee wanted Eddy’s songs to have an even more melancholy-sounding reverb, so he bought a grain tank and set it outside the Phoenix studio and put a microphone in it. “I had to have an echo,” he later explained. Drenched in reverb, Eddy now had a signature twangy sound. The result was 1958’s “Rebel Rouser,” a monster hit and the start of rock and roll’s love affair with the electric guitar. Over the next two years Eddy would have nine more Top 40 hits, all produced by Lee, inspiring everyone from the Beach Boys to George Harrison.

During this time a young producer named Phil Spector would travel from L.A. to Phoenix to watch how Lee got his sounds—especially the echoes. Spector, in turn, used Lee’s methods in the early sixties to create his famed “Wall of Sound” that made stars of the Ronettes and the Righteous Brothers and influenced countless records that followed, including some of Bruce Springsteen’s biggest albums.

Lee also unknowingly helped release the very first country rock album. In 1966 he started a label, Lee Hazlewood Industries (LHI), which produced and released dozens of singles and albums, including one by a proto-country-rock group called the International Submarine Band, whose singer and songwriter was a recent Harvard grad named Gram Parsons. The album, Safe at Home, was released in early 1968 (Lee called it “hippie-billy”), though by then Parsons had already quit to join the Byrds, whose sixth album, Sweethearts of the Rodeo, released later that same year, is usually regarded the first major label country-rock album. (Parsons was, arguably, still under contract with Hazlewood, who threatened to sue the Byrds. As a result, three of Parsons’ lead vocals were stripped off the record and replaced by the singing of bandmate Roger McGuinn.)

Perhaps Lee’s biggest impact on the music world came after his first “retirement” from the music business in 1964 (he said he couldn’t stomach the British Invasion), when he returned two years later and helped transform Nancy Sinatra into a major pop star with “These Boots Are Made for Walkin’.” The two would do a whole album of sublime duets in 1968, Nancy and Lee, a gothic pop masterpiece of melodramatic string arrangements and James Bond-style horns drenched in reverb. Lee was writing some of the oddest, most compelling songs of the era, odes to love and longing like “Summer Wine” and “Sand.” “Some Velvet Morning” went from minor key to major and a straight beat to a waltz to tell a mythic tale of sex and doom that many have covered and no one has ever been able to decipher. “I write songs with double and triple meanings,” Lee would later say. (He would also call them “simple songs filtered through complicated thoughts.”)

With Lee singing in a deep, gravelly drawl, countered by Sinatra’s bright and knowing alto, the two captured the darkness and light of the era. “He had the deepest voice I’d ever heard in my life,” noted Alexandra Sliwin, a singer in Honey Ltd., an all-girl band he produced. “I couldn’t even understand him. And I’d never seen anyone with a mustache like that. He was very Texan. He was very sweet and embracing of us, his ‘little darlins.’”

Lee, by this point divorced from Naomi, had become the mysterious outsider cowboy, an image he enjoyed promoting. Jack Nitzsche, a Hollywood musician and arranger, used to say that “the longer Lee lived in L.A., the thicker his Texas accent became.” But for Lee it wasn’t just about appearances. He was returning to Texas often, going to Port Neches to visit his parents and even attend high school reunions. His old friends were surprised when he came, says Harrison, but they were also pleased that he acted like he used to: like Barton Hazlewood, not like a big star.

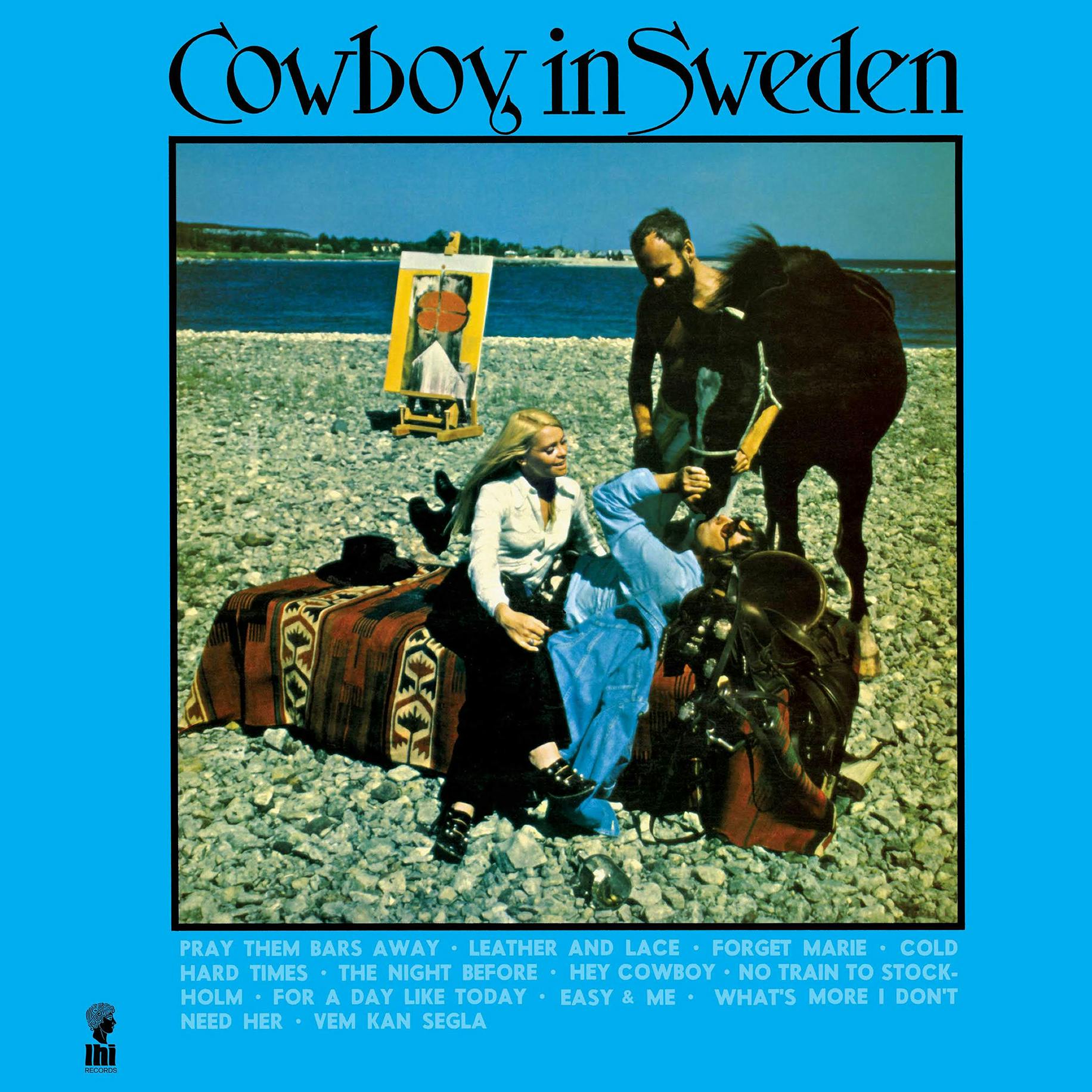

Though Lee was pleased with the fortune he’d made, he didn’t care as much about the fame—or Hollywood. By the end of the sixties he was an old man at forty, one who had lived through the Depression, World War II, and Korea, and paid more than his share of music business dues. So, in 1969, with dozens of hits and a recent album with Ann-Margret called The Cowboy and the Lady (he’d also done a couple of folkie albums and a surf album) he moved to Sweden. He told his high school friend Elton Jones that he was worried about his son getting drafted to go to Vietnam. “I’d rather my kids be in Sweden making love instead of war,” Jones remembered him saying. In Sweden, Lee embraced his cowboy persona fully, and was embraced in turn. In 1970 he starred in a one-hour flick for Swedish television called Cowboy in Sweden, a trippy film that featured a soundtrack full of his psychedelic pop-country songs.

Lee became a TV star in Sweden, made more albums, and narrated a bizarre documentary about his life called A House Safe for Tigers. The film tracked one of his return visits to Port Neches, this one in the mid-seventies. “Alcohol is the only way to fly back to Port Neches, Texas,” Lee intoned in a deep voiceover, “a town no one ever came from. I’m not sure I really left.” The camera showed him wandering the streets of the town, through the weeds of a shuttered gas station, peering into the grimy windows of the local theater and drug store. Lee, closing in on fifty, was in a ruminative mood, contemplating youth and death. “Flowers get to come back every year,” he said. “But the gods played a joke on us: We never get to come back.”

Returning to Sweden, Lee retired again from the music business and moved around some more (Paris and Hamburg, among other cities) before winding up in Glendale, Arizona, where, in 1993, he met a thirty-something woman named Jeane Kelley. The two hit it off; she didn’t know who he was at first, and he got a kick out of the fact that she had won a junior high school talent contest by singing “Boots.” Soon they were living together and he was sharing everything about his life with her, his ups and his downs. “He was angry with the music industry,” Kelley says. “He felt it had shunned him because he did what he wanted to do, not what was the latest trend.” It wasn’t long before Lee and Jeane, an Army brat from Killeen, began wandering the world: Phoenix, Spain, Las Vegas, Ireland, Florida. “We’ll stay for a year,” Lee would tell her, “and if we like it, we’ll stay.” Sometimes he would get bored, other times he just didn’t want people to know who he was.

But two decades into his retirement, the pop world finally caught up to the “obscure old fuck,” as he called himself. Through the eighties and nineties, bands like Nirvana, Pulp, and Sonic Youth discovered Lee, covered his songs, and sought out anything they could find about him. In 1999 the Smells Like label, which was founded by Sonic Youth’s drummer Steve Shelley, began reissuing his old records. (Eventually those went out of print, and in recent years Light in the Attic began re-reissuing them, as well as Hazlewood records that had never seen the light of day in the states.) All that attention seemed to wake him from his resentful slumber, and in 1999 he made something of a comeback, putting out an album of old jazz and pop standards he had heard as a boy. The title was pure Lee: Farmisht, Flatulence, Origami, ARF!!! And Me. He followed it with a performance at London’s Royal Festival Hall, playing for a whole new generation of fans as well as old-timers like himself, and then a European tour in 2002. Wallace remembered, “People treated him like a lost messiah returning from the desert.”

In 2000, at age 71, he returned to the Golden Triangle with Jeane. “I want you to see where I came from,” he told her. The two rented an apartment in Port Arthur, three miles from his teenaged home, and spent the next year living there. He drove her past his old house, as well as the spot where Janis Joplin’s home used to be.

Lee spent a lot of time with an old friend, Ira Scoggins, a pharmacist, and the two would go to Louisiana to gamble. Lee and Jeane would also head across the bridge to the riverboat casinos or rent a boat and go out on the gulf. They would drive to Billy Joe’s Bar-B-Q in Port Neches or various Cajun restaurants. Occasionally Lee would see old friends in public and sit and talk with them, rehashing old times.

Jeane was struck by how much he still missed his parents—each had died in the seventies—and by how much he enjoyed being back home. Wallace, who spent some time visiting Lee in Port Arthur, agreed. “He had an intense affection for the place,” he says. “I think it was attached to his fondness for his parents. And also, the music he had heard there. I think it was an affection for his childhood. You hear this innocence running through his work—a strong attachment to his childhood—a time before things got complicated.”

But Lee couldn’t stay in any place too long, not even the one where he felt most at home. His rambling ways got him moving again, back to Florida and finally to Las Vegas, where he died of renal cancer on August 4, 2007, not long after marrying Jeane in a drive-through ceremony.

“He was a Texan at heart,” she says, “just like me.” She remembered a European tour stop, where Lee was furious to discover the backstage food was all vegetarian. “I am from Texas!” Lee yelled. “We eat dead animals! I want dead animals on this table in twenty minutes or I do not go onstage.” The meat arrived, and Lee performed.

He was rude and sweet, innocent and depraved, proud and bitter. He absorbed everything he heard, saw, and read—from Port Neches to L.A. to Stockholm—and then made his own music in his own defiant way. The cowboy hat was just for show, as it is for most Texas singer-songwriters. The man who wore it was a lot more complicated.

- More About:

- Music