THE STATUTE OF LIMITATIONS HAVING mercifully expired, let me get something off my chest. Back in the sixties, when the great cultural wars were flaring up, I wrote for a while under the nom de plume M. D. Shafter. It was a way to confound the IRS, which had taken an inconvenient interest in about $1,000 in back taxes that I owed. This was the dawning of the Age of Aquarius, which followed the JFK assassination and Vietnam and foretold the acceptance of alternative lifestyles. Texas Monthly, Southwest Airlines, and the Armadillo World Headquarters were just peeking over the horizon.

Many writers and artists whose names are now mainstream fixtures chose prudence over ego back then. It was a way to survive while maintaining artistic integrity. I learned recently, for example, that the gifted illustrator and historian Jack Jackson adopted his trademark signature, Jaxon, as a method to avoid detection by his boss, Robert Calvert, who was the Texas comptroller of public accounts. Though his first love was history, Jackson had majored in accounting at Texas A&I (now Texas A&M-Kingsville) before moving to Austin and taking a grunt job in the Capitol basement. This may have been the only time in his life that he played it safe. “I wanted to be like Spinoza—grind lenses by day so I could do fun stuff at night,” he told me recently. Fun stuff was drawing subversive cartoons for the Ranger, the University of Texas student magazine, and completing work on his first comic book, God Nose, which was printed late one night with the help of his friends in the Capitol printing office. That’s right, citizens: The first significant underground comic was printed at government expense.

I had gone to see Jackson because I’d read his latest graphic novel, The Alamo: An Epic Told From Both Sides, and thought it was excellent and highly entertaining. “Graphic novel” is a fancy name for a 172-page comic book, but the history rings true and the effect is memorable. Jackson—who has won numerous awards in forty years as a cartoonist, cartographer, historian, and an illustrator and has published fifteen books, including Los Mesteños, the standard scholarly reference book on Spanish ranching—takes pains to research his subjects. For the Alamo book, he spent as much time studying the clothes, weapons, houses, and oxcarts of nineteenth-century Texas as he did drawing the panels of characters. Strange, then, that the gift shop at the Alamo, which is run by the Daughters of the Republic of Texas, will not sell his book. The DRT claims not to have room for it on its shelves, though I suspect there are other reasons. More likely, though they deny it, the Daughters object to Jackson’s faithful depiction of the hardships suffered by the Mexican army. He says that twenty years ago an earlier group of Daughters rejected his graphic novel on the life of Texas patriot Juan Seguín because a Mexican was pictured on the cover.

Jackson looks like one of his drawings. He has bushy gray hair, a floppy mustache, and the fixed scowl of a cantankerous, ascetic cartoonist who spends most of his time alone. A rare genetic disease similar to arthritis has crippled his hands, making it difficult for him to hold a pen. Nevertheless, he works at least six hours a day, every day, in the book-strewn studio behind his modest North Austin home. Work is his life, and it has been for years. Our mutual friend Bob Simmons, who lived with Jackson in San Francisco when a coven of expatriate Austin artists and musicians was running the Avalon Ballroom, the Family Dog, the Rip Off Press, and Rip Off Review, recalls, “He’d get up early and work all day, researching and drawing. His discipline has always been unbelievable.”

Growing up near Pandora, a virtual ghost town east of San Antonio, Jackson was a curious kid. He was fascinated by the flints and arrowheads he found near the old family cemetery, always wondering how this place and these people connected to him. His early books were mostly about Indians. Two of his kinsmen, he learned in his research, died at the Alamo: Thomas Jackson, of DeWitt’s colony, and Burke “Buck” Trammell, of Austin’s colony. Like most Texans his age—he is 61—Jackson began learning about Texas history by reading Texas History Movies, a cartoon book that originated at the Dallas News in 1926 and for three decades was distributed to all Texas elementary schools by Magnolia Petroleum Company. “I learned more about Texas from that book than I did from my history teacher, who, of course, was a coach,” Jackson says.

After college, at a most fortuitous time, Jackson followed his bliss to Austin. People who yearn for the city’s gilded age suppose they’re talking about life here thirty years ago, but the quintessential Austin experience happened in the late fifties and early sixties, when Jackson and an insightful band of young Texans, including most of the Ranger staff, shared a ramshackle apartment building called the Ghetto. Torn down years ago, it was located just off the UT Drag, near Dirty Martin’s, and it was center stage for those hardy pioneers of our fabled counterculture. Janis Joplin partied at the Ghetto. So did Gilbert Shelton, the creator of Wonder Wart-Hog and the Fabulous Furry Freak Brothers. And Joe E. Brown, the model for the Freak Brother called Freewheelin’ Frank and also a co-founder of Austin’s (and Texas’) first head shop, Underground City Hall, the forerunner of Oat Willie’s. And Wali Stopher, an elfin musician who posed for the photograph of Oat Willie that Jim Franklin used in his famous illustration.

“There were no prom queens at the Ghetto, no sports heroes or debate champs,” Simmons recalls. “These were the misfits who dressed in black in high school and read Kerouac.” They drank 35-cent quarts of Grand Prize at the Friendly Tavern and took refuge at a coffeehouse called the Id, where it was safe to listen to Miles Davis or recite poetry or share a recipe for hash brownies. Weary of getting beat up by rednecks, they had mostly migrated to San Francisco by 1965. My connection with this marvelous period was the privilege of publishing two articles and being listed on the staff box at Rip Off Review—under the name M. D. Shafter, naturally. By the mid-seventies, most had returned home to Texas. “Austin had changed,” Jackson remembers. “There were places like Soap Creek and the Armadillo, and the rednecks were blending in with hippies. I read in Rolling Stone that Doug Sahm was moving back to Texas. I figured if it’s safe for Doug Sahm, it must be safe for me.”

Too many of those hippie pioneers have died of drug overdoses or alcohol poisoning or bad luck. Shelton has been in France for years, living a millionaire’s life off the film rights to what the French call Les Fabuleux Freak Brothers. Franklin has disappeared somewhere in the French interior. Some of them sold out, but not Jackson. For years he tried to hide his counterculture connections, knowing that his fellow historians would never take seriously the work of a man who was the art director of the Family Dog’s psychedelic poster operation. Now he’s too old to give a damn. Last summer’s release of the Alamo book was his magnum opus. Life has been hard, financially, psychically, and emotionally—and is likely to stay that way, especially since the keepers of the Alamo refuse to recognize his work.

Between April and October of last year, Jackson wrote a series of letters to Kathleen Milam Carter, the Alamo Committee chair of the DRT, and to Virginia Van Cleave, the president general of the DRT. He enclosed his vita so they would know he was a real historian. He informed the Daughters of his family ties to the Alamo. His final letter begged to meet with the committee so that he might learn their objections and defend his work. He never heard back. “I hate to burn my bridges,” he says. “The DRT will have new officers in the summer. But I know what happened. As soon as they saw balloons coming out of the mouths of characters, they assumed the book was something like Batman.”

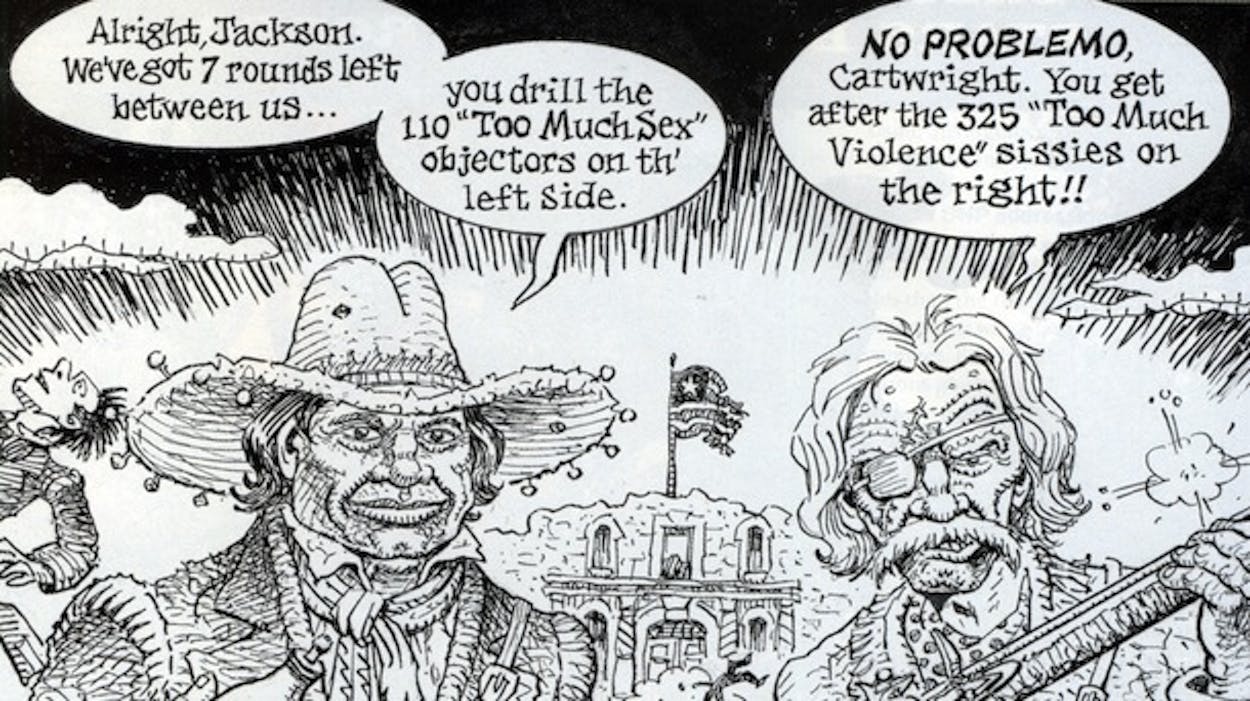

A week before Christmas, I traveled to San Antonio for a firsthand look at the Alamo gift shop and to meet with Carter, who gave me the same explanation she’d given Jackson. “We have five to ten books submitted every week,” she explained. “We can’t carry them all. If we add a title, we have to take a title down.” I had already inspected the Alamo’s meager shop, tucked in one corner of the museum, and had noted seven or eight books that seemed clearly inferior to Jackson’s. More than half of the shelf space was devoted to children’s books like When Grandpa Had Fangs: The Story of the Snake of the Alamo. I couldn’t believe they had banned Jackson’s work for this. “We don’t ban, and we don’t censor,” Carter replied, politely but firmly. “It was a business decision.” Alamo director David Stewart told me that 85 percent of the Alamo’s income comes from the gift shop. “We sell more shot glasses than books,” he admitted meekly. He had read Jackson’s book and found it “interesting,” he said but added, “I wouldn’t want my children to read it.” Too much sex and violence.

Violence, of course, is what war is all about. As for sex, I believe Stewart was referring to scenes of Travis and Bowie womanizing in the cantinas of old San Antone, which, though historically accurate, is not the DRT’s cup of tea. I didn’t ask if he thought the book had too many Mexicans.