I write in celebration of the Tahitian sailors who, centuries ago, made their way across thousands of miles of open, starless seas to reach the Hawaiian islands without the benefit of modern navigational technology. In order to detect ever-so-subtle changes in the ocean currents that could throw them off course, these noble primitives would periodically place their testicles on the wooden floors of their canoes. I am a Tahitian sailor. I have no computer.

Yes, I am one of the very few people in the world, it seems, who cannot tweet, e-mail, Google, Facebook, or word-process. I can’t even text while I’m driving. I am unconnected. The people who used to be my friends now take an anthropological interest in me, as if I were a member of a cargo cult in New Guinea or an elder of some isolated tribe in Lower Baboon’s Asshole. The only way I have of communicating with these people is by telephone, but most of them no longer bother to return my calls, even though I invariably punctuate them with a bright, cheery, increasingly desperate “Kink-a-doodle-doo!”

I’m typing this column on the same kind of machine I’ve been utilizing for more than a quarter of a century. It’s called a typewriter. You may not have heard of it. It’s a large contraption that makes a terrible racket and uses “ink.” On a recent trip to Hawaii, the security people were quite fascinated with it, and the other passengers took me for a mad scientist with a supercomputer. “I’ve never seen one before!” exclaimed a young girl in an Aggies T-shirt. “I can’t believe it!”

“Pinch yourself,” I said.

My no-tech lifestyle has not stopped me from providing what is now called “content” to the media outlets of the twenty-first century. Recently I typed up a story for the website the Daily Beast and faxed it to them. A few hours later my editor called. I could tell he was trying to be polite. “We got your fax,” he said. “The only two people who’ve ever faxed their work to us are you and Gay Talese.” I told him I didn’t mind the company. If you don’t know who Gay Talese is, you should Google him sometime. I can’t help you there. Hell, I can’t even Google Jesus.

It gets increasingly lonely to be the only one left on the outside looking in. I turn to old friends like Willie Nelson and Don Imus for wisdom and advice, but they’ve both gone radically high-tech and never miss a chance to twist the knife. To be fair to Imus, he’s always hated talking on the telephone. “You don’t have to join a chat room or download porn,” he told me recently, “but you ought to at least be living in the twentieth century.” Willie will use the telephone, but only when he finishes texting with Kourtney Kardashian. (Willie’s also on Twitter, they tell me; if my ass was as high as his ass, I’d be tweeting too.) Just as the Internet, e-mailing, and texting have put the final nail in the coffin of the lost art of letter writing, so too do they appear to have relegated Alexander Graham Bell’s seminal invention to the phone booth of history.

I’m getting it from all sides now. My old pal Steve Rambam, a private investigator, has been hounding me to go digital for years. Rambam has chased (and caught) Nazis in Canada, parachuted with the IDF, and found missing persons all over the world, so he’s hard to dismiss as a geek.

“Don’t be a moron,” he says. “How many books have you written?”

“Let’s see,” I answer. “I think it’s been about thirty-one books I’ve churned out—I mean, carefully crafted.”

“You see? We could be making those books available to a whole new generation. E-books! Audio books read by the author! I’ll set it up for you. You know those obnoxious little five-year-olds you see in the backseats of their parents’ cars listening to their iPods? Pretty soon they’ll be listening to Kinky.”

“Yeah, but I never liked saying f— in front of a c-h-i-l-d.”

It isn’t just Willie, Imus, and Rambam. Suddenly everybody I’ve ever met is inviting me to join the tech orgy. People are herd animals, I think to myself. Those who stray from the herd risk being left behind, even if the herd is headed over a cliff. The majority, it seems, is always wrong. The crowd always picks Barabbas. The crowd shouted, “Kill Jesus! Free Barabbas!” Well, it’s been a few thousand years and we haven’t heard all that much from Barabbas. He doesn’t call. He doesn’t write. He’s never saved a soul or even won a football game. Yet they come at me like smiling zombies, extolling the praises of this kind of computer or that kind of software; attractive, insane, unemployed young people whose lives are spinning out of control want to teach me how to text; and all across this wretched, wussed-out, Wi-Fi world, 500 million Facebook freaks want only to hang around after Elvis has left the virtual building. I am on Facebook, they tell me, but of course I’ve never seen it. The only time I ever see my face, as the Steven Fromholz song puts it, is when I’m looking at “The Old Fart in the Mirror.” I have, however, updated the title to one of my old songs: “Waitress, Please, Waitress, Come Sit on My Facebook.”

It feels as if we’re being dragged kicking and screaming into the twenty-first century by people who have nothing to say and many ways of saying it. Mankind’s consuming passion for technology itself can be described as Edgar Allan Poe once described the game of chess: “What is only complex is mistaken (a not unusual error) for what is profound.” I continue to cling to the antiquated notion that real cowboys don’t tweet. There are just fewer and fewer of us around. The eighties, they say, was the decade of high-tech demarcation. Those born during and afterward are considered to be the “digital natives.” The language comes naturally to them. Those born before are the “digital immigrants.” Try as they may, they will never be as adept or facile. Then, of course, there are the “illegal aliens” like me. We just want to get into the buggy and head back to the ranch, but we can’t because we don’t have GPS.

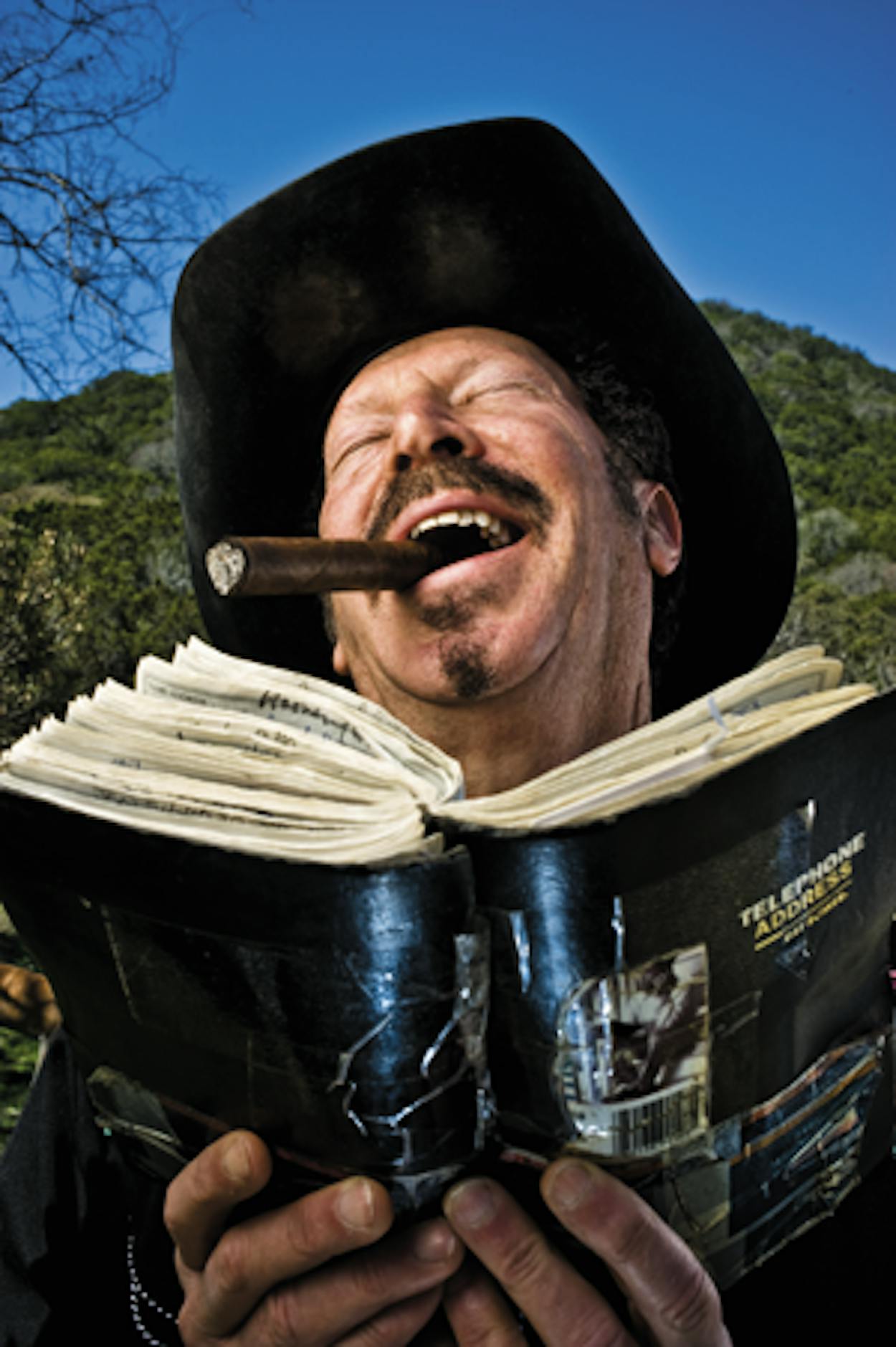

But maybe I’m being too hard on the rest of the world. Anyone under five reading this undoubtedly envisions me as a bitter old hermit, pacing the floor of my rustic lodge, puffing on a cigar, continuously mumbling Joseph Heller’s mantra: “Every change is for the worse.” A shrink might say I was suffering from Spartacus syndrome, which is always doing the opposite of what everybody else is doing. (There may be some truth to that; for instance, I do mourn the passing of Thousand Island salad dressing.) And my no-tech stance has deprived me of many conveniences. For example, a computerized address book. The names and phone numbers of the friends, lovers, square dancers, and serial killers I’ve met as I’ve wandered in the raw poetry of time are all stored in the same bulging, weather-beaten black phone book I’ve had for thirty years or more. About half the people in the book are dead; unfortunately, it’s the wrong half. Would a BlackBerry or some such device be more practical and efficient? Of course it would, if what you cared about in life is merely being practical and efficient.

I’m hardly blind to the blessings of the computer and the Internet. If your name is Willy Loman and you’re going over your sales inventory, a computer might be helpful. If you’re a 57-year-old pedophile in New Jersey, you might use the Internet to pretend that you’re a 27-year-old surfer in San Diego. You might contact a 14-year-old girl in Montana who’s really a middle-aged vice cop in Miami. (Incidentally, I despise pedophiles, but I have to admit, they do always slow down in school zones.)

But I’m also well aware of the digital downside. If you’re a creative person or an artist, i.e., ahead of your time and behind on your rent, the computer should not be your instrument of choice for poetry, fiction, or music. I have noticed that even Willie, a techno-geek if there ever was one, will bypass the laptop sitting right in front of his nose to scribble song lyrics on scraps of paper. Maybe it’s just force of habit, but I think there’s more to it. I think a true artist knows that if he’s able to technologically tweak something to death, it’ll never be great. He must have the mind-set that subconsciously tells him to get it right the first time or tear up the page and throw it in the fire. (By the way, never say anything like that to a techno-evangelist. I vividly remember the hubbub that was generated by humorless, constipated bloggers during my campaign for governor when I referred to the Internet as “the work of Satan.” It was worse than when I called Garth Brooks the Anti-Hank but not quite up to the level of hate mail I received when I wrote a column in TEXAS MONTHLY unfavorable to hunting.)

Philosophically, up until now I have assumed the mantle of a Luddite. We Luddites take our name from our inspirational leader, Ned Ludd, a disgruntled stocking-knitter in Nottingham, England, who, in 1811, destroyed wide knitting frames and other textile machinery in a passionate, if somewhat misguided, effort to stop the industrial revolution. Ludd, of course, did not succeed. Ludd, according to some scholars, did not even exist. He did, however, provide future generations with a stirring and enduring motto: “If it ain’t broke, break it.”

As a disgruntled stocking-knitter myself, I was prepared to live out the rest of my days in a no-tech mode. Then something happened that changed all that forever. I belched, farted, and tweeted at the same time. It was an e-piphany. I’d always heard that if you belched and farted at the same time you would die, and perhaps, in a sense, I did. At least the old Kinky died, but a new, equally tiresome Kinky was born. Next thing I knew I was sitting across a small table from Rambam with just a bottle of Jameson and a microphone. Our mission was to record 31 audio books without strangling each other. My three dogs, Brownie, Chumley, and Sophie, as well as other nearby residents of Utopia Animal Rescue Ranch—sixty dogs, three donkeys, six pigs, and a rooster named Alfred Hitchcock, who crows precisely at noon—lend at times a decidedly bucolic flavor to the narration of these mystery plots supposedly taking place in New York. Ah, well, that’s the producer’s headache; my problem is reading stuff I’ve written 25 years ago without slashing my wrists. Because I’ve forgotten the first half of my life, I also can’t remember how some of my mysteries ended. In other words, they still hold up pretty well. It’s remarkable to me that the five-year-olds Rambam assures me will soon be downloading my recitations straight to their iPods from Amazon or iTunes were not even born at the time these books were written. Neither were their parents. I trust I shall survive being discovered twice.

Even though a brave new world of technology is opening up, I still have a few qualms about believing in it completely. Life, according to Willie, is fraught with many phases and stages, and as the pendulum swings back and forth, it occasionally strikes a direct hit on your trusty Tahitian testicles.

As Barbara Jordan’s grandpa told her when she was five years old, “Love humanity, but don’t trust ’em.” This also applies to technology. Albert Einstein was once asked what weapons he thought might be used in World War III. Einstein said he didn’t know, but he felt fairly certain that World War IV would be fought with rocks.