All that year, my father and I worked on the movie, Summer of the Shark. It was 1977; I was nine years old. By then, I saw him only on weekends. For three years, he’d been away, finishing medical school, serving out his time in the Army, and when he came back, he didn’t live with my mother and me. He bought me a tripod, a hand-cranked editor for splicing footage, yellow boxes of film. We made fake blood with red dye and Karo syrup, wrote out copies of the script in pencil on notebook paper, cut a wooden fin with a jigsaw and glued it into a groove in a four-by-eight wooden plank.

And each weekend, my father took me to visit his friend, a woman who lived in one of the giant new apartment complexes sprouting up all over Houston. The first time we parked behind the complex, under a long tin shed that covered a line of shabby cars, he said we needed to have a talk. He reminded me of everything he’d bought me, all we had done together for the movie. I understood, didn’t I, that it would be better not to tell my mother about his friend? It would only make my mother upset; we didn’t want to upset her, did we? Of course we didn’t. And I wanted to keep doing things with him on the weekends, didn’t I? You’re a smart kid, he said.

It was my mother who drove me and the five other boys I’d persuaded to be in the movie from Houston to Bolivar, the fin sticking out the passenger window of her battered green Ford Maverick. She was one of those indomitable Texan women who would do such things as take six boys to the beach on her own to allow her son to make a movie; I wonder, now, at what mixture of guilt and love impelled her.

Two of the boys with us were brothers from the East End neighborhood where my mother and I had always lived, a cluster of brick bungalows and clapboard houses across the street from Hughes Tool. At night, the sky glowed Halloween orange and trains moaned and clanged. Geraldo and José Luis had moved there from Mexico a couple of years earlier. José Luis was a year or so younger than me, scrawny and quiet. Geraldo was a few years older and worked each day after school with their father, a machinist. Their father, like mine, had left home, though this was a fact we never mentioned. We saw each other every day. We had free run of each other’s houses, but to say that we knew each other well would not be exactly true. Like most of the children in the neighborhood, they spoke little English, and I spoke almost no Spanish. I am not sure how we communicated, but I had persuaded José Luis to be in the movie. Geraldo had come along to protect him.

The other three boys, Oscar, Robert, and Mark, went to my new school across town, where I had gone since my father returned. Though he did not live with us, my father paid my tuition, and so he decided where I would go to school. The new school, part of a world of identical houses and winding suburban lanes, was different from the Dominican Montessori downtown where I had gone before, as exotic and intimidating to me as another planet. I made my stand there with the movie, bluffing the boys that a Time magazine cover story on Jaws—“Summer of the Shark”—was about the movie I was making, that they could be making too.

Our first morning in Bolivar, we rose early and went to the beach, lugging a leather camera bag, a tripod, a canvas director’s chair, and the wooden fin. Gray Gulf waves rolled in under a gray sky, pushed ashore by a stiff wind. We set up on a rise near a gravel road to film the first shot of the movie: José Luis sprinting down to the surf, inexplicably, toward his doom.

Unwrapping the black plastic cartridge of film, clicking it into the camera, a gunlike Cine Kodak Super 8 I’d found in my grandfather’s study, my hands trembled; I could not believe that the movie was finally real. I squinted through the viewfinder, called “action,” pressed the trigger. The camera whirred. Inside the viewfinder, everything was just as I had imagined it, and I wished, angrily, that my father were there, to see what I was doing.

Next, we got in the water and trawled the fin through the surf, trying to keep the plank submerged, while my mother filmed from the shore—all of us except José Luis, who was too small to help, and Geraldo, who seemed to want nothing to do with the movie. I shouted to my mother, hectoring her, to make sure she got the shots right. The movie rose or fell, I knew, on that fin.

When the sun was high, my mother called us in for lunch. We were staying at my uncle’s beach house, a single room with a kitchen, toilet, beds. Before we ate, we went to rinse off in the cold concrete shower downstairs, except Geraldo and José Luis, who hadn’t gotten in the water. Oscar grumbled that they hadn’t helped with the fin.

Who are they, anyway? Oscar asked. Why did you bring them?

Mark and Robert stared at me quizzically. Mark was a shaggy-haired ragamuffin, sweet-tempered, none too bright; Robert, blond-haired, blue-eyed, was at the head of the class, like Oscar. Oscar was one of only two Latinos at my new school, and he lived in the nicest house I’d ever seen.

I shrugged, lowering my eyes. I couldn’t explain to them who Geraldo and José Luis were; in that moment, they seemed strange to me too.

I don’t know, I said.

The conversation moved on to the boys’ favorite topic, speculation on which orifice of a woman’s body babies came from. I knew the answer, because my father and his friend, whom he never called his girlfriend, had given me a lecture on the facts of life, but I did not want to think about my father and his friend. I did not want to think about how I had already betrayed Geraldo and José Luis. Rage burned through me and stung my eyes; I wanted them to talk about the movie.

Our work that afternoon did not go well. We filmed a scene in my uncle’s beach house, in which Oscar, Robert, and Mark, Coast Guard officers, discussed how they would kill the shark. The boys, dressed in brown school uniforms in the blazing heat, were restless and hadn’t memorized their lines. Oscar egged them on. He wound up Mark, especially, trying to get him to mock Geraldo and José Luis’s accents. I didn’t know how to stop him; I was convinced that if I tried, all of the boys would quit the movie.

Years later, I would make the mistake of telling Oscar and Robert about my father’s friend. They would circulate drawings they’d made of my father and her, grotesqueries that bore little resemblance to the things I’d told them but seemed truer, as if they knew the secret truth of my life that was hidden from me. By then, Geraldo, José Luis, and I had become no more to one another than faces in the street.

But in 1977, none of that had happened yet. In August, a few weeks after our trip, we all gathered in my mother’s dining room for the premiere of Summer of the Shark. Robert and Mark came with their mothers. Geraldo and José Luis were there with both of their parents, who sat stiff as statues next to each other, taking care not to touch. Only Oscar and his parents didn’t come.

My father was there, in his business suit, bullying and proud, clearly itching to be anywhere else. My mother, in a yellow sundress, seemed timid, reduced, as she always did around him. I didn’t know whom I hated more—him, for humiliating her, or her, for letting herself be diminished by him.

I passed out hand-written programs. Someone turned off the lights, and I switched on the projector. Images flickered onto the wall. I knew, from editing it, that the movie was not as I had envisioned it would be—especially the ending, when the shark destroyed the Coast Guard boat, a plywood box that my father and I had built. But I also knew that one shot—the most important shot—had worked.

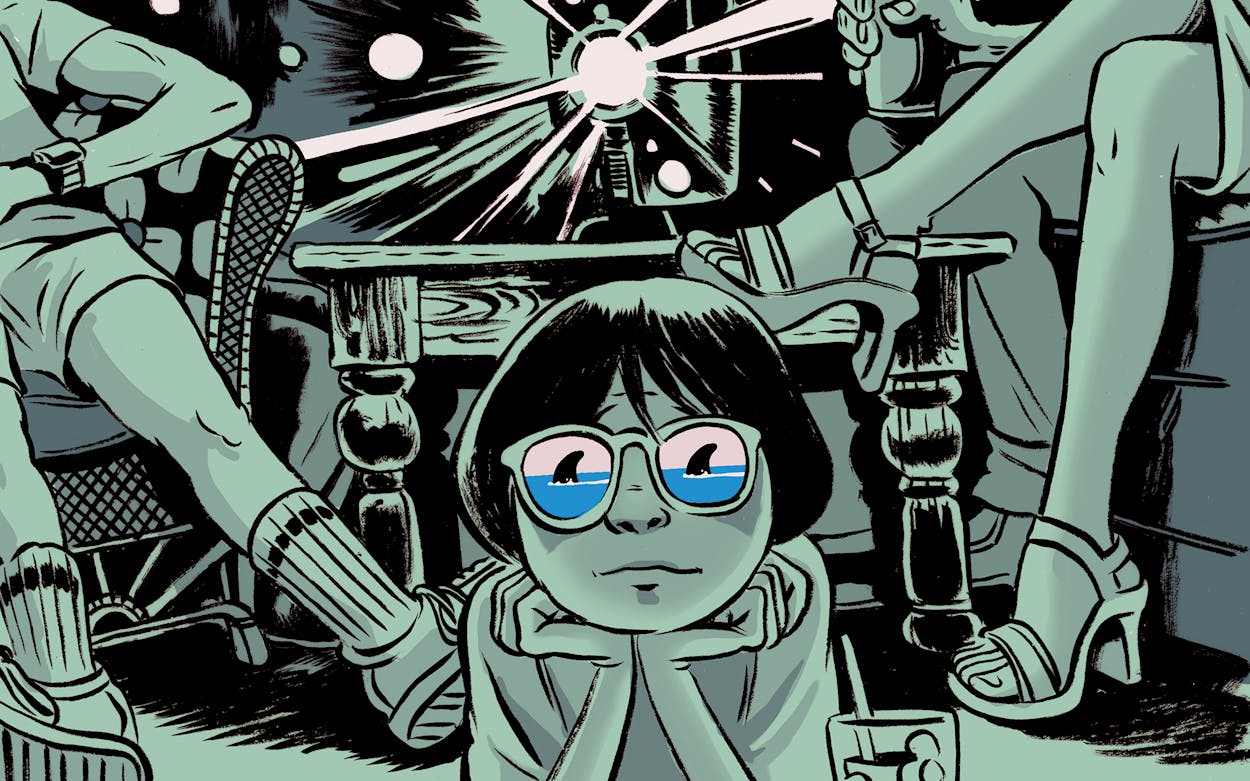

When the fin crossed the wall, I felt it, a question, a mystery, just as when I’d shown the boys the cover of Time magazine. The gray wedge cut through the water, and for a moment, it was real, and it had nothing to do with my father, or the woman in the apartment complex, or the strangeness I felt when I saw Geraldo and José Luis. I kept my back to everyone, leaning closer to the movie, trying to outpace all that was gathering behind me in the dark.