Spring football just makes sense. Americans adore football, but it enjoys the shortest season of any major sport we follow. Even as NFL ratings dip and the league finds itself in a bizarre PR battle with the president, more Americans watch and love football than any other sport by a wide country mile. There’s a clear market for more of the game come springtime.

Yet historically, spring football leagues haven’t amounted to much. Currently, there’s the four-team Arena Football League; the six-team Indoor Football League; and the extremely limited Spring League, in which four teams meet to play two games each in one city over the course of a week. Previously, there was the USFL—a league that was successful in the spring, but which moved its schedule to the fall at the behest of Donald Trump, who owned the league’s New Jersey Generals, and subsequently folded—as well as the original XFL, which played one season in the spring of 2001, introducing fans to outsized personalities like He Hate Me and diverting attention off of the field to give viewers an inside look at the cheerleaders’ locker room during games. (There are also fall leagues that appear from time to time, like the United Football League, which was funded in part by Mark Cuban for a few years in the early 2010s, and the short-lived FXFL, which failed to materialize promised teams in markets like Austin.)

But with two well-funded leagues preparing to launch in 2019 and 2020, the time may finally be right—although Vince McMahon’s rebooted XFL may face a tougher road than the Alliance of American Football.

When McMahon announced earlier this year that the XFL would be returning in 2020, it was a surprising move. In the announcement, which declared that XFL players would be required to stand for the National Anthem before games, McMahon indicated that his new league would try to gain disaffected football fans whose politics left them feeling alienated from the NFL.

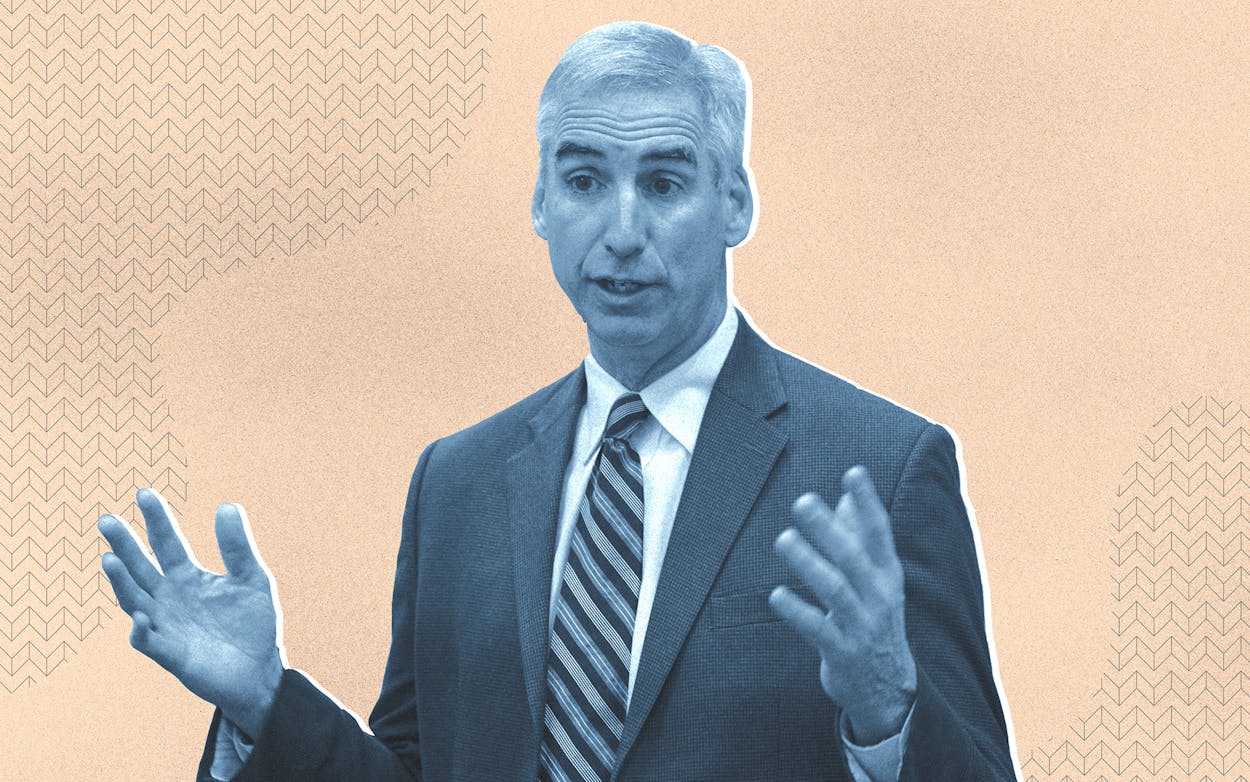

On Tuesday, the league made another announcement: Oliver Luck, former NFL and NCAA executive (and Oilers quarterback), would be its CEO and commissioner. Luck is likely a familiar name to Texans: He played quarterback for the Houston Oilers from 1982 to 1986, serving as Warren Moon’s backup in his final three seasons. Then, after receiving a law degree at the University of Texas, he returned to sports, first as head of the NFL Europe developmental league, then in 2001 returning to Texas to serve as CEO of the Houston Sports Authority, which oversaw the construction and financing of Reliant Stadium and Minute Maid Park. He went on to become the first president of the Houston Dynamo Major League Soccer team, who won titles under his leadership in each of his first two years. (He’s also the father of Houston native and quarterback Andrew Luck, who currently plays for the Indianapolis Colts.) In 2014, Luck became executive vice president for regulatory affairs at the NCAA.

Luck’s positions at successful organizations make a stint at the wild-card XFL a surprising gambit. The last iteration of the league flamed out spectacularly, and this time around, the XFL won’t simply be competing with fan loyalty to the NFL. It’ll also be competing with the Alliance of American Football, which will launch a year before the XFL plans to start playing games.

The AAFL has quickly established a toehold in the football world. It’s announced locations for seven of its eight teams, and recruited a variety of well-regarded coaches who’ve achieved success at the NFL and college level, including former Vikings head coach Brad Childress, former 49ers coach (and Baylor legend) Mike Singletary, Florida Gators Hall of Fame coach Steve Spurrier, and former San Diego Chargers coach Mike Martz (who won a Super Bowl with the team). It has impressive backing with Charlie Ebersol, son of original XFL co-founder Dick Ebersol, as CEO and legendary NFL front office man Bill Polian as head of football, along with a broadcast deal on both network CBS and CBS Sports.

The XFL, meanwhile, hasn’t established much of anything. We don’t know any of the cities it’ll play in or how it plans to compete for talent with the AAFL. We don’t know how fans will be watching games (McMahon has suggested that he plans to focus on digital streaming). And we definitely don’t know if there’ll ever be an audience for two pro football leagues playing games in the spring.

It’s surprising to see someone like Luck leave a job with a secure organization in order to roll those dice. If the AAFL succeeds, Luck’s league will compete with a successful organization that already managed to find an audience and got a year’s head-start on the XFL. If the AAFL fails, then Luck will have to convince fans and broadcast partners that spring football is viable, even if it failed the year before. Either scenario is a tough one.

It makes sense that McMahon would recruit him: Luck has a strong reputation, enviable connections, and a great deal of success in both the business of football and the business of launching new sports leagues. It’s possible that McMahon threw piles of money at him, and it’s possible that Luck believes strongly enough in the XFL’s mission that he’s willing to take a chance on entering an unenviable situation. In any case, if the XFL plans to go to war with the AAFL—to say nothing of the NFL itself—it’s definitely going to need a general like Luck. Why Luck wanted the XFL is more of a mystery.