The kid was a full-blown sports prodigy almost from the time he could walk. He was driving golf balls at the age of two, beating adults when he was ten. In youth baseball he hit so many home runs that the league installed a twelve-foot net over the fence. He responded by clearing it, once even breaking a window in a nearby house. When he was in seventh grade, he could stand on the 50-yard line, take a crow hop, and throw a football through the goalposts. He was descended from a long line of ferocious competitors—boxers and football players and drag-boat racers and cockfighters and scratch golfers and people who hated to lose even a friendly card game with their own children. Over the generations that fierce desire to win had been distilled repeatedly, reduced to a powerful concentrate that ran in the kid’s veins like an electric current. In high school he was a two-sport athlete: a spectacular, record-setting quarterback and an All-District shortstop who hit .416. As a nineteen-year-old redshirt freshman at Texas A&M, he set the world on fire, electrifying college football fans with his speed and swagger on the way to winning the Heisman Trophy. The kid never stopped moving. If he wasn’t on the field, he was hunting and fishing in the forests and creeks of the Hill Country, where his parents lived, or the lakes and piney woods of East Texas, where his family has deep roots. And even then he hated to lose, had to catch more fish and bag more bucks than anyone. The kid was wired in every possible way to need to win, no matter the game, no matter the opponent. But on the evening of August 4, 2013, he was facing the possibility of a major, soul-crushing defeat.

It was the night before Texas A&M’s fall training camp, and several hours earlier, the news had broken that the NCAA was reportedly investigating the kid for getting paid during the off-season to sign memorabilia, a violation of the league’s amateurism rules. Instead of strolling into camp the next day as a conquering hero, he would arrive under a cloud of doubt, with questions swirling about whether he would even get to play. As he practiced that week, the storm of negative publicity just got worse, as allegations from various anonymous sources rolled through the Internet and denunciations rained down on him from all sides.

For anyone paying attention, the moment had a distinct sense of déjà vu. One year earlier, when the kid was still unknown, he had hit what had seemed at the time like his lowest point. It was the early morning of June 29, 2012, and he was sitting in a College Station jail cell, having been arrested for fighting and booked for disorderly conduct, failing to properly identify himself, and carrying phony driver’s licenses. The arresting officer’s report identified him as Johnathan Paul Manziel. Age: 19. Height: 6″1′. Weight: 195. It also noted that his breath smelled of alcohol and that “his speech was slurred when he spoke.” The mug shot showed him looking grim, glassy-eyed, shirtless, and obviously very unhappy.

For Johnny Manziel, “the incident,” as his family and coaches called the 2012 arrest, had marked the end of a long, slow slide into a dark place. It had begun when he’d been redshirted in his first year at Texas A&M, meaning he could practice with the football team but not play in games. Though redshirting is common enough, for a kid as desperate to play and win as Manziel was, it was a minor disaster. He hated riding the bench; through fall practices he felt adrift, without purpose. When his redshirt season ended and he joined the team’s official roster, in the spring of 2012, he seemed to have lost the spark that had made him so good in the first place. He played worse, in his own estimation, than he’d ever played in his life. It seemed impossible that he could land the starting quarterback job, especially after a mediocre performance in the intrasquad Maroon and White Spring Football Game. Jameill Showers, a cannon-armed sophomore from Killeen, would likely be A&M’s quarterback that fall, and Manziel would sit, miserable and aimless, all that competitive juice turning sour in his veins. As spring gave way to summer, he fell even further into a funk, fighting with his family and, as he puts it, “just being too wild of a college kid.” And then came the arrest. The week that followed was full of urgent meetings with his coaches and parents to discuss his future and news in the local press about how Manziel had blown his chance to ever be A&M’s starting quarterback. He became deeply discouraged, telling his mother that if this was what college football was all about, he wasn’t even sure he wanted to do it anymore.

But fate had other plans. Just over five months after the incident, a dapper, bright-eyed Manziel, known to the nation and to vast numbers of sports fans worldwide as Johnny Football (and to many online as the more emphatic Johnny F—ing Football, or JFF), stood on a stage at the Best Buy Theater, in New York City, and became a legend: the first college freshman in history to win the Heisman Trophy. In that time he had emerged from the obscurity of the Texas Hill Country—unheralded, unhyped, and underrated—to exhilarate the nation with a frantic, improvisational style of play that sometimes seemed as if it belonged more in a video game than on the gridiron. In the Southeastern Conference, America’s toughest football conference, he set the all-time record for total offense, breaking 2010 Heisman winner Cam Newton’s record in two fewer games. He broke the legendary Archie Manning’s 43-year-old SEC record for offense in a single game. He and his insurgent Aggies shocked the world by beating national champion Alabama. And in case there were still doubters—with Manziel, there are always doubters—a month later, at the Cotton Bowl Classic, he engineered the wholesale destruction of a very good, eleventh-ranked Oklahoma football team. His team, which many had predicted would struggle that year, finished 11-2, ranked fifth.

But Manziel did more than just send 350,000 living Aggies into paroxysms of joy with his victories on the field. His Heisman season unfolded at a time when deep currents of change were running through Aggieland itself. A number of years before his arrival at Texas A&M, the university had launched a major campaign to finally make the public understand that it was no longer the same old narrowly regional school that labored in the eternal shadow of the University of Texas but the diverse, highly ranked global research university it had quietly become. In fact, its 2011 decision to join the SEC was in large part an attempt to refashion its image as a national university. The pitch had been working: applications since 2003 had nearly doubled. Still, old feelings and stereotypes lingered.

Then along came the kid. Perhaps the most amazing thing he did last fall—and what may turn out to be his most lasting contribution to the Aggies—was to allow Texas A&M to finally emerge, as if from a chrysalis, with a fully formed new identity. It is hard to pinpoint exactly when it happened. For some it was the Alabama game. For others it was the nationally televised stomping of its former Big 12 rival and tormentor Oklahoma. But it happened. Ask any Aggie. With an enormous whoosh that you could feel in the farthest reaches of Aggieland, those old burdens were suddenly cut loose: the chip on the shoulder about UT; the Big 12 and all its baggage; the old idea that A&M would never be anything more than a dull regional school. The signs at Kyle Field saying “This is SEC Country” suddenly seemed less like parting shots at UT than beacons of a new age.

“It was amazing to experience it,” says vice chancellor of marketing and communications Steve Moore. “Everything was bigger, the ocean was wider, the sky was higher.”

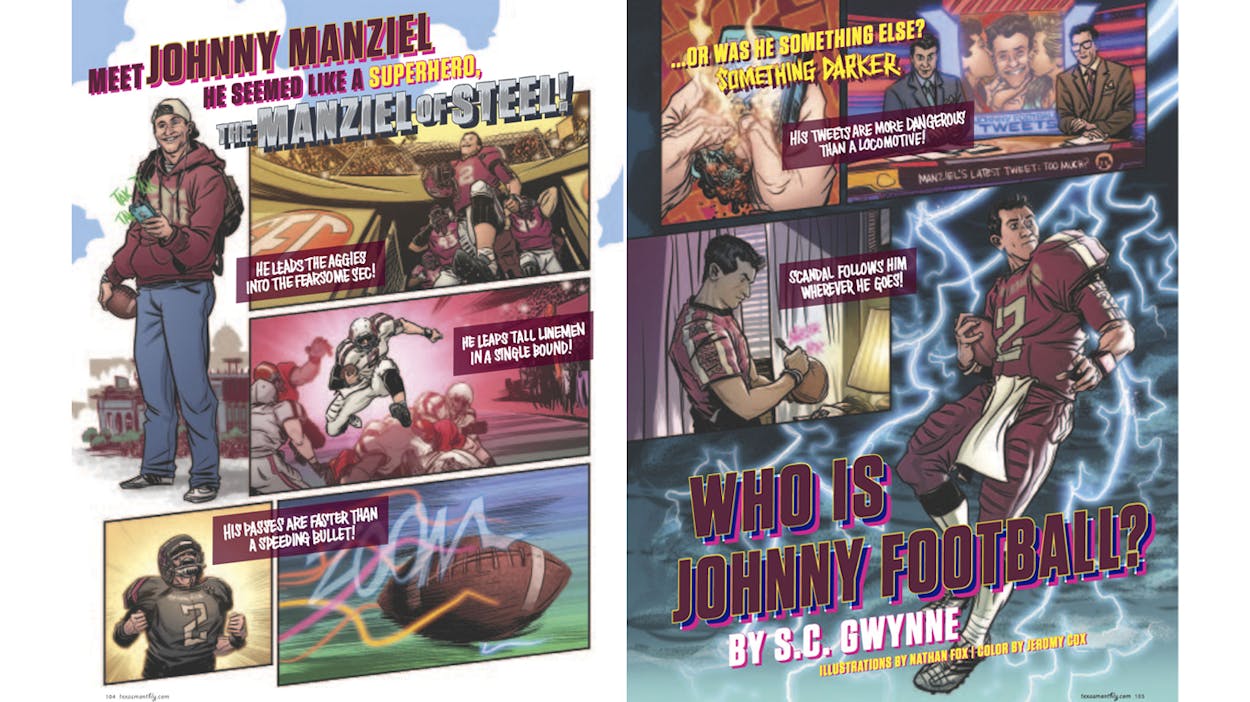

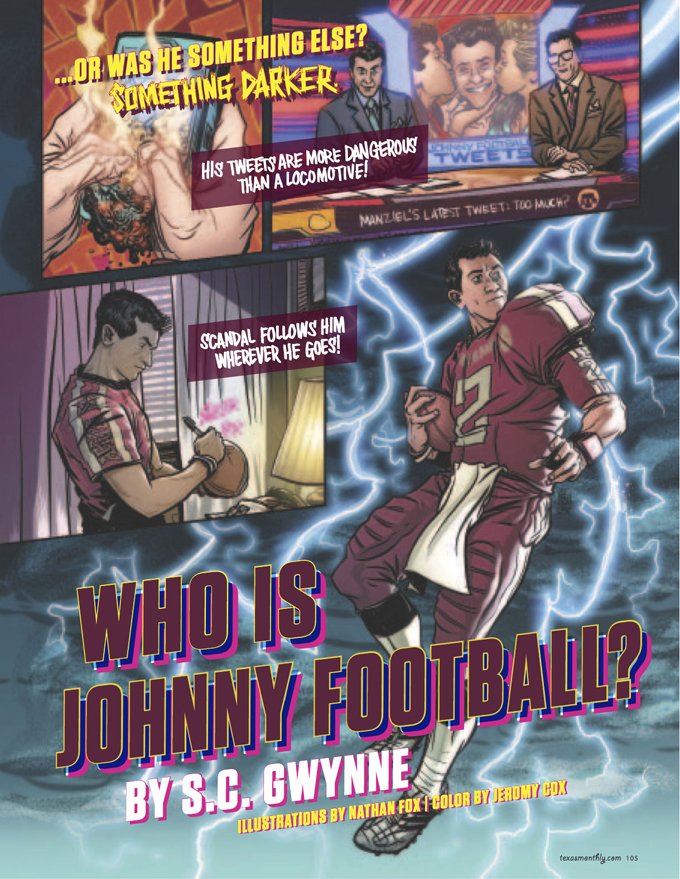

But not necessarily for Johnny Manziel. For the kid, who was instantly famous and who was not shy about enjoying the fruits of his gigantic, Bieber-like celebrity, the sky began closing in on him as soon as he won the Heisman. In the months since then, he has lived in a world of constant controversy, much of it of his own making. No college athlete has ever achieved quite the level of fame that Manziel has, and no Heisman winner has ever lived in as relentless a media environment. Everything he does is examined and found wanting. It has appeared, at times, as if Manziel, like an immature superhero, possesses a special power he does not yet know how to use. He sends a careless Tweet and blows up his entire month. On online message boards and comment threads, vast numbers of critics—many of them fans of rival schools, it should be noted—wait eagerly for the great football star to fall dramatically to earth. And on August 4, they seemed to get what they were waiting for.

It will likely take months, if not years, to sort out the impact—to say nothing of the facts—of Manziel’s alleged actions. But this much is clear: his greatest strength is perfectly intertwined with his greatest weakness. Everything he touches, bad or good, goes uncontrollably viral. On the football field, he cannot be stopped, and off the field, the stories and pictures and rumors about him that spread throughout our hyped-up, 24/7, crazy-making news cycle cannot be stopped either. One year ago, he was unknown; today he is a kind of mythical creature. It makes you wonder, What planet did this kid come from?

- More About:

- Sports

- SEC

- NCAA

- College Football

- Aggies

- Kevin Sumlin

- Johnny Manziel