With barely a peep from preservationists, another piece of Texas history was razed in mid-January as bulldozers unceremoniously demolished the prison rodeo arena in Huntsville.

The brick-and-concrete building, which hadn’t held a prison rodeo since 1986, had structural problems, and prison officials determined that repairs to the unsafe stands would be too costly. Representatives from the city offered to help pay for the repairs, but as with all similar entreaties involving the arena over the years, the Texas Department of Criminal Justice, which oversees the state prison system, rebuffed the offer.

“They just weren’t interested,” said Jim Willett, director of the Texas Prison Museum and a former warden. The criminal justice department “just doesn’t want to be in the rodeo business.”

Jason Clark, a TDCJ public information officer said, “The decision was made to demolish the arena because it was in a deteriorated condition and was a safety hazard because of the public roadway that runs alongside of it.”

When demolition crews began tearing the arena down, “it brought all these memories back,” said Ann Buxton, an administrative assistant for the agency. “This was a major historical thing. It should have been preserved.”

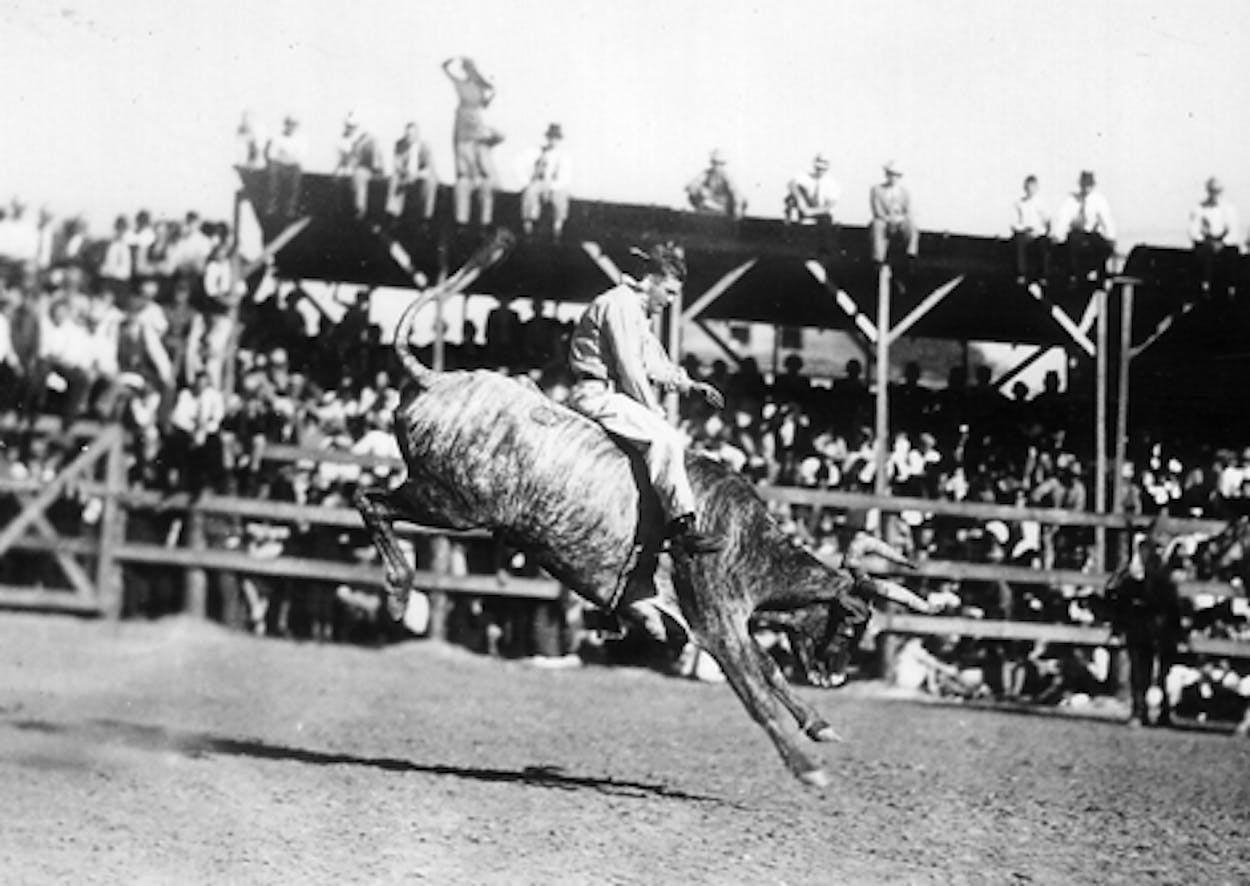

Advertised as “the wildest show behind bars” and “the wildest show on earth,” the spectacle was a major draw in this town of 38,000. Lee Simmons, the Texas prison system’s general manager during the early 1930s, created the event—the first of its kind in the country—and from the first Sunday performance in October 1931, on the site of the old prison baseball field, the rodeo succeeded far beyond the wildest dreams of its sponsors.

The original wooden stadium only seated a few hundred, forcing organizers to turn away many fans. When attendance topped 15,000 in 1933, the organizers realized it was a money-making hit, and the major “free world” rodeos looked to the event in Huntsville as an example of the growing popularity of the sport. Seating at the arena was doubled in 1938 to accommodate the growing number of spectators, and in 1950, a $1 million arena with a capacity of 20,000 was built—a red-brick structure that matched the Walls Unit, as the Huntsville prison compound next door is commonly known.

With the performers wearing their black-and-white-striped rodeo uniforms, sewn by female inmates at the Goree Unit, the accolade “best cowboy to ever wear stripes” was a title worthy of respect.

The rodeo also featured—alongside the usual rodeo fare like bull and bronc riding—unique daredevil events that allowed more inmate participation as well as additional thrills. Colloquially referred to as “redshirt” events (for the brightly colored shirts worn by the contestants), these dangerous stunts were a fan favorite. The most popular redshirt event was “Hard Money,” in which inmates attempted to snatch a tobacco sack from the horns of a bull. The standard prize for the sack was $100, but with contributions from fans that amount could swell to as much as $1,000.

“Things got a little intense then,” Willett said. “There were guys who weren’t all that brave for $100, but they’d get pretty brave for $1,000.”

The rodeo also regularly brought in top-name “free world” entertainers to play concerts, including country singers like Dolly Parton, Ray Price and Willie Nelson, as well as prison bands like the Huntsville Prison Band and the Goree Girls. In the 1960s, the latter combo featured the former stripper Juanita Phillips, better known by her stage name, Candy Barr.

The prison rodeo served as a stage for the skill and drive for many, but few were better than a black cowboy named O’Neal Browning. Browning—who was fittingly born around 1931, when Simmons first began laying plans for the rodeo—started riding bulls as a sixteen-year-old when he was working at the Houston Fat Stock Show and Rodeo, held at the Sam Houston Coliseum. His father, who wanted him to stay at home and work the family farm, objected and, even after his son began earning prize money at local rodeos, would subject him to beatings when he came home.

Later, Browning, in a drunken rage, killed his father with an ax. The crime earned him a life sentence, and during his incarceration he became involved with the prison rodeo. In 1950, his first rodeo as an inmate, he won the Top Hand title, which was awarded for the most prize money earned over the four Sundays in October. Because Browning was only nineteen, his mother, who feared for her son’s safety, had to sign a release before he could perform. Browning went on to win an unprecedented seven Top Hand awards over three decades.

Simmons created the rodeo as a form of recreation for the inmates. Now, according to the state’s Offender Orientation Handbook, the team sports allowed in Texas prisons are softball, volleyball and baseball.

One section of the arena remains standing today because it was built over an inmate dormitory that is still in use. That lone portion, bearing a slight resemblance to a red-brick pyramid, stands vigil over a raw, empty lot.

The property will eventually be utilized for maintenance and repairs of criminal justice department vehicles. Inmates will do the work.