Twenty years ago Larry McMurtry, the preeminent chronicler of Texas, was estranged and far removed from the state. He had moved in 1969 to Washington, D.C., and opened a rare-book shop. With his son, James, he lived in a pretty little town across the border in Virginia and kept a small apartment above the store. He wrote that he returned one summer to see if he still “knew or felt anything about Texas”—and essentially decided, Nope.

Yet McMurtry had made his early mark with books that elegized that most revered Texas icon, the working cowboy. He knew the life firsthand. His grandfather began ranching Archer County’s bluestem prairie soon after the defeat of the Comanche and Kiowa made that practical. Most of the patriarch’s twelve children scattered into the Panhandle; in time the clan owned 150,000 acres. McMurtry’s dad grazed cattle on 5,000 acres of land around Archer City. He was a wiry, driven man, hard to please and averse to nonsense. McMurtry grew up mending fence, talking to cowhands, daubing cattle sores with a foul disinfectant called screwworm dope. His role models were terse grizzled uncles who equated horsemanship skills with strength of character.

But from the start, McMurtry was a townsman too. His mother didn’t want to raise a family in that lonesome ranch house stuck between a dirt road and a humpbacked knoll called Idiot Ridge. Though McMurtry’s imagination roved the pastureland, he spent more hours of his youth in a small white frame house in Archer City, a bleak and windswept burg near Wichita Falls.

For most of his adult life, Larry McMurtry fought those roots the way that area ranchers grub out pestilent mesquites. He chopped, yanked, and poured more than a little poison into the soil. McMurtry ran from Texas, and perhaps himself, even as he became the dominant Texas writer of his time, or any other time. He used to wear a T-shirt that read “Minor Regional Novelist.” It was an academic tic, this preoccupation with labels of “major” and “minor,” but his talent was large. So was his ego and the chip on his shoulder. He came, he often remarked, from a bookless town in a bookless part of a state that had no literature of any worth. Texas themes and Texas settings, he contended, could be gravely injurious to a novelist’s career.

Still, he found ways to write about his region’s agrarian past and urban redirection that were moving, dramatic, and new. Since the early sixties, McMurtry has published seventeen books; Lonesome Dove, his masterpiece, won the Pulitzer prize in 1986. He has informed a generation of reading Texans about themselves, and his professional success has legitimized Texas, in a literary sense.

As a 23-year-old, McMurtry drafted two novels, Horseman, Pass By (1961) and Leaving Cheyenne (1962), that handsomely debunked the western genre of Zane Grey and Louis L’Amour. All the Indians in North Texas had been chased off to Oklahoma, and guns were just ranching tools carried about in pickup trucks. Horses and saddles were still required in order to do the work; but the new prestige item was a Cadillac. The twentieth century had reduced the ranching West to a grim essence of trying to make money. Working cowboys were a tragic dying breed. Their entrapment by the myths and traditions of the past made them all the sadder.

The first book was promptly made into the film Hud, with a mesmerizing Paul Newman in the antiheroic title role. Though Hollywood later made a shambles of Leaving Cheyenne, it was the stronger novel. As the years wore on, its author would grouse about its enduring popularity. Only the very young or the hopelessly romantic, he held, could buy its premise: Two men could love and sleep with the same woman all their lives, yet their friendship would never really suffer. Good point. But Leaving Cheyenne holds up as one of his three best novels because of the loveliness of the prose, the tartness of the dialogue, and the staying power of the characters. In that book he discovered his gift for humor.

Working cowboys were a tragic dying breed. Their entrapment by the myths and traditions of the past made them all the sadder.

In the same vein, a much-praised essay, “Take My Saddle From the Wall: A Benediction,” appeared in the 1968 collection In a Narrow Grave. He wrote about his family elders—especially an Uncle Johnny who rode off to work the great vast spreads of the Panhandle, went broke running his own ranch, started another, lived to drive a Cadillac, and in the end was so arthritic from getting thrown and fallen on by horses that he had to order his cowboys to fix him in the saddle with baling wire. McMurtry’s dad could never understand why his son also had to write about his Uncle Johnny’s contraction of venereal disease. To tell the whole story, McMurtry tried to explain.

He lived in Houston from 1963 to 1969. At Rice he was an English graduate student and a teacher of writing, and while managing a shop called the Bookman he refined another great passion—finding, collecting, and dealing in rare books. He didn’t encourage his students much. In fact, he discouraged them. What he did was show them the life, the possibility. Success could happen. He hosted the Merry Prankster busloads of Ken Kesey, a chum from their Wallace Stegner fellowship days at Stanford (Kesey worked on One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest, McMurtry on Leaving Cheyenne). Tom Wolfe wrote about Kesey and McMurtry’s friendship in his chronicle of the sixties, The Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test. McMurtry was special and knew it.

In 1972 one of his screenplays, written in collaboration with director Peter Bogdanovich, was nominated for an Academy award. McMurtry had blazed through his third novel, from which the script was drawn, following a return to Archer City on a family matter. Three days there reminded him of everything about the town he didn’t like. He described a place where teenagers sodomized heifers, where married women had never heard of orgasm, and where a preacher’s son sexually abused a five-year-old child. “The Last Picture Show,” the author all but sneered, “is lovingly dedicated to my home town. ”

McMurtry has never consented to interviews by journalists; he did not grant one to me. But he has responded to scholars’ inquiries, and in his essays he hardly shies away from the subject of himself. When the movie was playing to great acclaim, he wrote ruefully in a Washington, D.C., journal: “By the time the book was published (1966), I was aware it was too bitter—Archer City had not been cruel to me, only honestly indifferent, and my handling of my characters in my book represented a failure of generosity for which I could blame no one but myself. ”

The book had caused no great stir, even in Archer City. In hardback it sold only about nine hundred copies. The movie production pumped money into a long-suffering economy. But the subject matter was touchy, and a number of the movie folk behaved as if they were brought up in Babylon. In the local backlash, some nasty comments were directed at McMurtry.

In a 1975 essay for the Atlantic, McMurtry explained his move from home: “I got tired of dealing creatively with the kind of mental and emotive inarticulateness that I found in Texas.” He faulted the state for its excess of Oldsmobiles. “I work in Georgetown,” he wrote smugly, “where I am surrounded by Mercedes and Volvos.” McMurtry as a yuppie and East Coast snob. A youthful marriage had left McMurtry seared, with a son in diapers to raise, and much of that pain was absorbed in Austin. He took a swipe at that “dismal” town and its endless production of “third-rate” books, music, pictures: “I don’t believe it can claim a single first-rate artistic talent, in any art. ”

In Austin, an inescapable victim of rant was McMurtry’s friend Bill Brammer, who knew he had squandered a large talent but also knew he had written an exceptional political novel, The Gay Place. “Larry didn’t seem all that miserable when we were living in the same house,” said Brammer, hurt by the snub. Two years later, Brammer was dead, and McMurtry later dedicated a book to his memory.

With son James grown, McMurtry embarked upon a nomadic phase, roving between apartments in Washington, D.C., Arizona, and California. He hasn’t owned a car in two decades. He would present his American Express card at the desks of the Hertz company, choosing not a Mercedes, Volvo, or Oldsmobile—rather a Cadillac or Lincoln. McMurtry as a fat cat nouveau riche. He would park them for days with the meter running—instruct the Hertz folks to get him a new one when the floorboard got trashy.

By the early eighties, he no longer avoided Texas so much. He opened bookstores in Dallas and Houston, and his dad had died a few years earlier, so his family had need of him in Archer County. So he added to his way stations the small ranch house on Idiot Ridge. But Texas had vanished from his published fiction. He wrote inferior novels variously set in Hollywood, Washington, D.C., and Las Vegas. If rootlessness was the disorder, it was not the most glaring symptom. McMurtry had made his youthful mark as a meticulous stylist. Commercial success allowed him to dispense with careful revision and polished turns of phrase. In middle age he churned out books that were sloppy. During that period, the film adaptation of his Houston novel Terms of Endearment won a batch of Oscars. But McMurtry was at the lowest point of his career. He seemed to have lost confidence in his abilities, and he admitted that he had spent a decade writing books he didn’t like.

In 1981 McMurtry expounded on the sorry state of Texas letters to Ronnie Dugger, the founding editor of the Texas Observer. McMurtry’s resulting Observer essay, “Ever a Bridegroom,” set off an amusing furor. Not only were Texas writers ignorant of urban complexity and hung up on the frontier past; they were lazy! “John Graves likes to farm, William Humphrey likes to fish. . . . Our best writers’ approach to art is tentative and intermittent: half-assed, to put it bluntly. Instead of an infinite capacity for taking pains they develop an infinite capacity for avoiding work, and employ their creativity mainly to convince themselves that they are working well when in fact they are hardly working at all… Until Texas writers are willing to work harder, inform themselves more broadly, and stop looking only backward, we won’t have a literature of any interest. ”

Literature is a judgment safely rendered generations down the line.

It was McMurtry’s most endearing joke on himself. Political cartoonist Ben Sargent provided the art for the Observer essay; the title page had three old codgers sitting on a fence, clad in chaps, one twirling a lariat, another wearing a Texas Ranger badge, under the heading “Wild West Show.” The intended caricatures were McMurtry’s longtime backwardlooking whipping boys—the late J. Frank Dobie, Roy Bedichek, and Walter Prescott Webb—but Sargent’s cartoon provided Texas literature with a prescient glimpse of three other aging Texas Rangers, Gus McCrae, Colonel Call, and Jake Spoon. Soon after the Observer flap, McMurtry returned to an unproduced film scenario he had written with Peter Bogdanovich in 1972. His novelization of that material became his wild West classic, Lonesome Dove.

The plot concerned the decision of three old-timers to drive a herd of Longhorns from the Rio Grande to Montana and their loves and adventures along the way. McMurtry plucked much material from an oral history, The Trail Drivers of Texas, and J. Evetts Haley’s biography of Charles Goodnight. I wished he had strayed further from his historical sources. Like McMurtry’s Gus McCrae, Charles Goodnight’s friend and partner Oliver Loving was wounded in an Indian fight, lost a limb, and died from gangrene. Like the book’s evil renegade Blue Duck, the Kiowa chief Satanta cheated his captors with a suicidal head-first leap out a prison window. I wanted the final satisfying confrontation between Gus and Blue Duck that McMurtry seemed to promise. But the book had the emotive power of an avalanche. His characters, male and female, were irresistible. Robert Duvall, the superb actor who starred in the TV miniseries, has said that for him, the role of Gus McCrae was as classic and rewarding as the role of King Lear.

Coming at a time, 1985, when the dominant Texas faith—making money off oil and land speculation—had swamped the bankruptcy courts, McMurtry’s book and its success reaffirmed our more appealing myths, tradition, and pride. “Literature” is a judgment safely rendered generations down the line. But among Texas writers, word of his Pulitzer Prize buzzed and jangled like frontier telegraph lines. A member of the ranks had reached deep and gotten the great book within him; and the world paid heed. I had the pleasure of carrying the news to one small group. We were fishing. Arriving in camp, I said, “McMurtry won the Pulitzer!” Leon Hale, a fine Houston writer, had the perfect inarticulate Texas response. He dropped his jaw, grinned, and said slowly, “No shit.” John Graves, McMurtry’s longtime friend and fellow elegist, released a pleased chortle and walked off toward the river, unlimbering his fly rod.

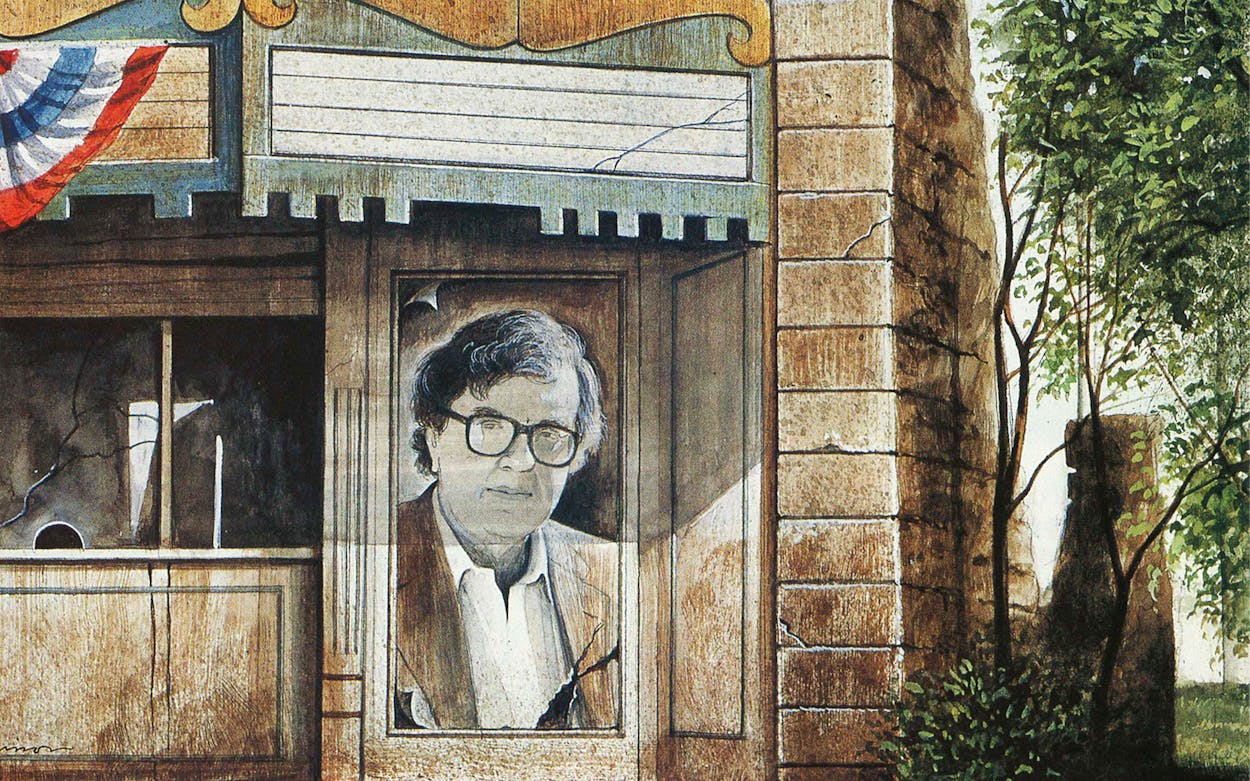

At peace with Texas in his writing, McMurtry gradually returned in his way of life. Though he kept the small apartment in Washington, he moved his most prized possession—his personal book collection—back to the ranch house on Idiot Ridge. In 1987, just off Archer City’s downtown square, he opened the Blue Pig Book Shop. The store is managed by his lively sister Sue Deen, a former rodeo queen and quasi hippie and a lifelong horsewoman. McMurtry’s other sister, Judy McLemore, owns Archer City’s real estate title company. His brother, Charlie, is an English graduate student in Denton. His mother lives in a retirement home in Wichita Falls. Family seems to be the strongest tie. James McMurtry is thirty now—a promising Austin songwriter and recording artist. James’s two-year-old son, Curtis, is Grandpa’s pride and joy.

McMurtry worked well at the ranch but found the rural telephone service wanting. In 1989 he bought Archer City’s only mansion, just down the street from the white frame house where he grew up. When he was a boy, the mansion belonged to an eccentric oilman and rancher named Taylor. Neighborhood kids tormented Old Man Taylor, a sort of local Boo Radley, but McMurtry also sought him out. The old man gave him books.

After the Taylors died, the yellow brick mansion became the Archer City Country Club. The town found it had scant use for such a thing, especially when the price of oil hit $8 a barrel. So, at 52, McMurtry established primary residence back on the street where he started, in the biggest house in town. The golf course remains squeezed close around the mansion’s fences. Nobody is yet calling him Boo Radley, but Archer City is an odd place for a rich and world-famous author to settle down. Empty stores, wan antique shops, and oil-field winch trucks abound. The old picture show is a crumbling ruin on the courthouse square.

During the mansion’s restoration, he spent much of his time in Manhattan, serving as president of the American chapter of PEN—an organization dedicated to freedom of expression. His election to that post was emblematic of his acceptance and esteem; he was the first non-New Yorker president of PEN since the twenties. Twenty-odd years ago, McMurtry considered Texas origins a yoke around his neck. Shortly before he left the state, he wrote that if a Texas author could explain the Kennedy assassination and get LBJ impeached, the New York literary establishment would beat a path to his door: He might even get to meet the glamorous intellectual Susan Sontag. That statement bristled with youthful ambition and insecurity. Now a Texas pedigree can open doors for young writers, and Susan Sontag, who preceded him as president of PEN, is one of many fascinating female friends who come to Archer City for stays in the guest rooms of his mansion.

Over the years, other famous friends have included Native American writer Leslie Silko and actresses Cybill Shepherd and Diane Keaton. His newest frequent companion is a student, a former legal services executive from Tucson, Arizona. Another close friend, Texas writer Beverly Lowry, thinks his reputation for writing knowingly and well about women is deserved, and she offers an explanation: “I’d never known a man who talked about the emotional life—about falling in love—so openly, and with such self-deprecating humor. I had barely met him. I was startled by it, but also comforted, and very comfortable. You just don’t expect that—especially in a guy from the Southwest. ”

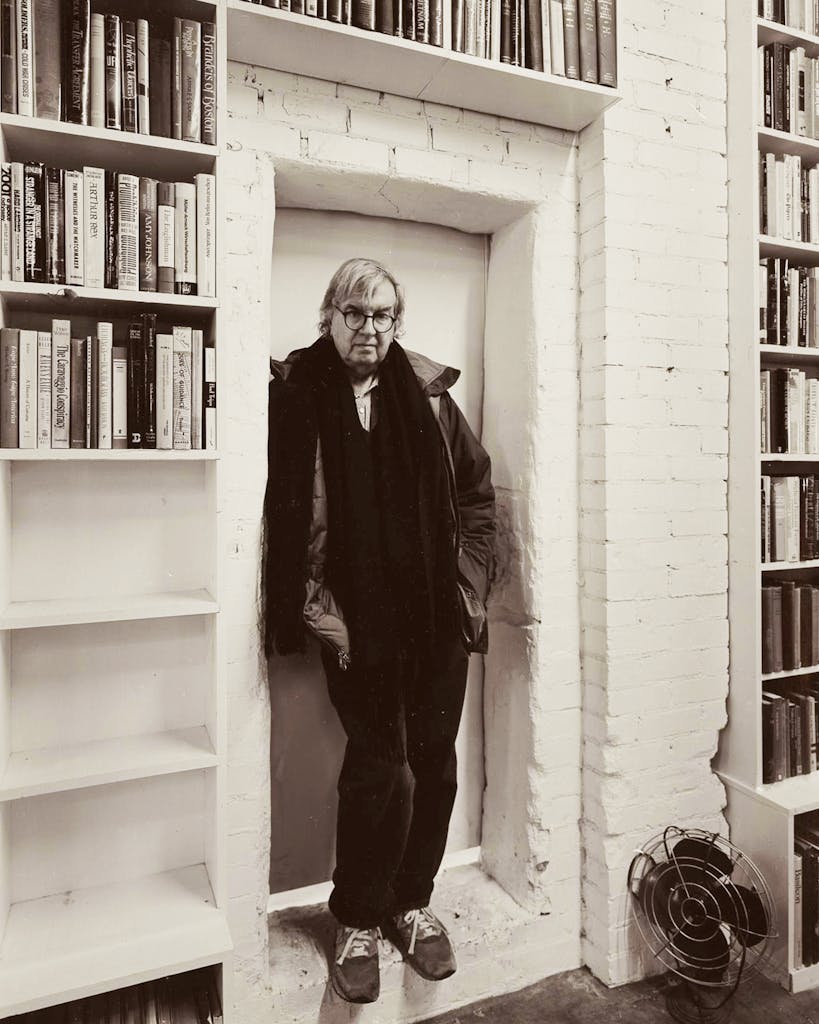

Since Lonesome Dove, the strongest and most revealing of his five books has been Some Can Whistle (1989). It featured a wealthy fiftyish writer, who is set up in eccentric isolation at a place like Idiot Ridge, beset with fears of self-parody, haunted but also assuaged by loves long past, bewitched by a young grandchild, annoyed by all this nagging talk about fatty diet and cholesterol. McMurtry had heart surgery last year, and the months of convalescence laid him low. A couple who retired to Archer City from the oil patch run a nice little restaurant called the Cottage Tea and Antiques; they still send over covered dishes, making sure he eats right.

The restored mansion is filled with one-piece furniture and endless shelves of books. Also there’s a “bone room” of animal skulls, femurs, a table made from bones—they came, perforce, with a book collection acquired in Philadelphia. He dislikes air conditioning, which he calls “homogenized air.” His powers of concentration are legendary; friends recall him hard at work, getting in his daily five pages, with an infant son balanced on his knee. Now he finds himself drawn to stories about people who are getting on in years. Cranky sequels, discoveries anew. Golf balls clear the privacy fence from time to time, ricochet off the roof, roll across the lawn. When McMurtry’s working well, he probably doesn’t notice.

- More About:

- Books

- Longreads

- Larry McMurtry

- James McMurtry

- Archer City