The tiara was only a simple band of rhinestones, but to Jessica Graham it was everything. She thought about it when she was mucking out the stalls, and she thought about it when she was trying to halterbreak her spindly legged colt, and she thought about it when she was walking back to her mother’s house, bone-tired, at sundown. She had thought about winning the rodeo queen crown ever since her romance with horses began: When she was six, her father gave her an old blue roan that was gentle and never pitched her off, and in the summers she would lope him through the shade of persimmon trees and thick-limbed sycamores until it grew dark. Back then, when the rodeo came to Llano, she had marveled from the stands as the contestants raced into the arena on horseback, shimmering in sequins and satin. Her mother, Maxanne, had run for rodeo queen in 1978, and now that Jessica was fourteen, she could make a run for queen herself. “I’d wear the tiara everywhere I went if I won, and the sash too,” she said, breaking into a grin. “You’d have trouble getting the dang thing off me.”

Life in Llano County can be hard and lonely and short on ceremony, but once a year, when a caravan of horse trailers and circuit riders rolls into town, the rodeo holds out the promise of transcendence. The rodeo is the biggest event of the year in Llano, and the queen’s crowning is the most talked-about part of the show—unless, of course, a bull rider gets thrashed within an inch of his life. This northern edge of the Hill Country provides few other diversions, only the wide-open space to daydream and ride, and Jessica spends a great deal of time doing both. Most days she runs her mare, Princess, bareback through the sandy-bottomed creek that cuts through her family’s land, a four-hundred-acre spread that has been in her family for three generations. Hers was not among Llano’s prominent ranching families, and for Jessica, winning the crown was both a point of pride and a preoccupation. Even the boy she was sweet on proved to be little distraction; when she was with him, she was thinking about how the crown should be hers.

The pageant consisted of four contests of equal importance: personality and appearance, horsemanship, parade float design, and ticket sales. The new queen would be announced at the rodeo in June, after all the judges’ scores had been tallied. The pageant was notoriously political: Winners were picked less often for their horsemanship abilities than for their family name, and Graham wasn’t much of a name to run on. That made Jessica even more determined to try. She would compete against four other contestants: Tasia Bauman, a varsity cheerleader and an aspiring model; Jennifer Myers, a sophomore who was the sister of the reigning rodeo queen; Kim Feller, a popular senior who was headed to Tarleton State in the fall; and Ashley Leifeste, the champion barrel racer and golden girl of Llano, who, though only fifteen, had won almost every rodeo title she had set out to win.

Jessica was the youngest of the group, and though she had just finished her freshman year at Llano High School with Ashley and Tasia, she had little of their grace. Still, she was good with her horse, and she was hungry to win. She had played the scene of her crowning over and over again in her head: the roar of the crowd, the glow of arena lights on a warm summer night, the moment when she would lean down low in her saddle to accept the victor’s bouquet of red roses. That night she would shine while the whole town was watching.

The women’s culture club of Llano occupies a restored Victorian house just off the town square, its polished interior appointed with white lace curtains, Oriental carpets, and a bust of Beethoven that gazes out over the drawing room. Twelve days before the rodeo, the pageant began here in earnest with the personality and appearance contest: a question-and-answer session that would be scored by a panel of five women, each picked for her impartiality. Jessica and the other girls hovered around the punch bowl and waited for the judging to begin. They had been told to dress for the occasion in Western wear, not the kind they usually wore—blue jeans, ropers, and cotton T-shirts—but something more queenly. For the benefit of the judges, some wore broomstick skirts, concho belts, or pointy-toed boots. Tasia, who was always perfectly turned out, wore a black-suede cowgirl ensemble complete with star-shaped appliqués and white-leather fringe. Jessica made do with a simple denim dress, her sun-streaked hair worn straight and neat.

The contestants waited to be summoned into the wood-paneled dining room, where they would be asked “Who is your role model?” and “What are your future plans?” along with the inevitable question, “What would you do to make the world a better place?” Jessica was the last to be called. When it was her turn, she sat ramrod straight in front of the judges with her hands clasped in her lap, smiling her most genuine smile. She spoke of how much she admired her stepfather (“There’s nothing he can’t do”) and how much she hated snobbery (“No one should look down on anyone else for being poor”) and how someday she hoped to be an equestrian photographer and horse trainer—responding to every inquiry with a courteous “Yes, ma’am.” She giggled perhaps more than she should have and shifted nervously in her wood chair, which creaked during the long silences when the judges marked their evaluation forms. They had been asked to appraise poise, style, and grooming as well as confidence and sincerity, since the winner would represent Llano not just at the rodeo but in all Hill Country parades and festivals throughout the year.

By the end of the evening, the girl most people in town had already pegged as the pageant’s likely winner had charmed the judges. Ashley Leifeste was starkly beautiful, with corn-silk hair she wore long and loose and a tomboy’s confidence: the sort of self-possession that, in the rodeo arena, guaranteed she always clocked in at the fastest time. As a champion barrel racer, she knew how to compete, and she told the pageant judges exactly what they wanted to hear: The queen should be an accomplished horsewoman, not just a girl who liked riding for show. The queen should better represent Llano by participating in all the local rodeos. Ashley also recounted her own hard-luck story of how her bid for the crown had nearly been thwarted in March, when she tore up her knee so badly that it required surgery. “My doctor told me I couldn’t ride for a while, and I was so mad because I wasn’t going to miss the rodeo for anything,” she said. She had decided to run for rodeo queen while in her hospital bed, and after a grueling regimen of physical therapy, she told the judges, she was ready to ride.

The judges were won over. “My favorite candidate by far,” one wrote. Another judge, who gave her a perfect score of 100, noted, “Ashley will make a very good rodeo queen.”

Llano is named after the Llano River, which begins in the plains of West Texas, winding its way past Junction to the center of this 3,564-person ranching town. Most activity in Llano still revolves around the town square, which is quiet and shaded by pecan trees, and whose centerpiece is the courthouse: a majestic three-story structure of pink granite that speaks to Llano’s more ambitious past. German settlers came to Llano County in the 1840’s and 1850’s to claim ranchland that was unlike any other in the Hill Country, made so by its own peculiar geography: Though limestone bedrock surrounds the county in all directions, the county itself rests on the Llano Uplift, a vast dome of granite that long ago pushed its way upward to form a mass of land where the grass grows knee-high.

Cattle trailers still rumble through town past Buttery Hardware and the Nailhead Spur Company and Leatherworks and the Lan-Tex Theater, and local news is traded at Duncan’s Barber Shop beneath pictures of prize-winning livestock. But ranching is on the wane in Llano County, as it is throughout cattle country, for the sheer economics of it are unworkable. “Property that goes for two thousand dollars an acre out here is worth no more than three hundred dollars an acre if you’re working the land,” said district attorney Sam Oatman. “The river dried up in 1954 or 1955, and it was so parched, you could walk across it. Ranchers had to come into town and work at the hardware store or the filling station to make ends meet. That’s when things began to turn.” The men who a generation or two ago would have worked on area ranches are now contractors or propane dealers. Land buyers are more often urban refugees from Austin enamored with the idea of country living. “It’s funny to see people from the city without even a pair of Western boots buying duallys and snuff and thinking that makes them cowboys,” groused one rancher.

Though ranch life is fading, nostalgia for it—and for the rodeo—has hit Llano full tilt. The rodeo craze got going in the early nineties when local heroes Tee Woolman, Speed Williams, and Rich Skelton were winning big in team roping. Llano, in the words of several locals, went “rodeo crazy.” The town already had a long rodeo tradition: The first one took place in 1919, and it became an annual event in the thirties. Still, nothing compared to the sort of enthusiasm for rodeoing that Woolman, Williams, and Skelton sparked. Before then, as ranching had declined and girls were no longer as skilled at horsemanship, the rodeo queen pageant had become something of a town embarrassment. Some winners could barely stay in the saddle, and one queen nearly fell off her horse during her victory lap. But Llano now boasts more than thirty arenas for calf roping and team penning, and girls who run for queen know full well how to ride.

The rodeo queen they admire most of all is Kippi Kuykendall, Miss Rodeo Texas 1995, who lives on a ranch just west of town with her husband, professional saddle bronc rider T. J. Kenney. Kippi spent her high school days competing all over Central Texas and loved the arena so much that she missed her prom to compete with her horse, Streak. She can boast of winning no fewer than 49 buckles and nineteen saddles, some still enshrined in a velvet-lined shadow box at her parents’ farmhouse.

But her rodeo days are mostly behind her: Now a 29-year-old schoolteacher with the straight-backed bearing of a true rider, she barely resembles the girl with the Aquanetted hair and painted-on smile in the glossy Miss Rodeo Texas pictures. “They always wanted my hair to be poofy, and my hair just isn’t poofy,” she said, radiant in overalls and no makeup, her long blond hair spilling down to her waist. Her success led her to the national pageant in Las Vegas, which turned out to be less about horsemanship than about fashion and artifice, and she had no taste for it. “I was not living to be Miss Rodeo America. Great if it happened, but I was just a rodeo girl who wanted to ride.” The competition, she said, “was cutthroat, and I was so naive.”

She was flipping through a photo album filled with memorabilia, past her ribbons and news clippings and postcards from the state finals in Abilene. Then she turned a page and came to a picture of herself when she was fifteen, just crowned Llano Rodeo Queen. She smoothed it with her hand and sighed. “Gosh,” she said, staring hard at the photo. “I was so young then.”

In the race for rodeo queen, Ashley was the girl to beat. She was beautiful and popular, and since she could afford to compete in rodeos around the state, she had been able to make a name for herself as a barrel racer. Her family was one of the oldest in Llano County and lived on a vast spread of grassland near House Mountain, not far from where the Leifestes first settled in the 1840’s. The earliest Methodist services in the county were held in the shade of Augustus Leifeste’s live oak tree, and the Leifeste name has been ubiquitous in Llano ever since. Most of Llano agreed that Ashley was fated to win, just as they agreed that Kim Feller’s chances were slim: She was the only contestant who didn’t own a horse, who wasn’t a practiced rider, and who, as a senior headed off to college, would not be in Llano to serve out the rodeo queen’s reign. The way Jessica saw it, the other girls would be tougher competition: Tasia was pretty, Jennifer was good with her horse, and Ashley was the one she spent her time worrying about. Ashley’s best friend was Tasia, though ever since their mothers entered them in the same beauty pageant for babies, the two had competed against each other. (Ashley won glamour baby; Tasia won beautiful baby.) And from the time they were little girls, Ashley had been the one to run faster, jump higher, win more. She was always in motion, her blond hair whipping behind her as she raced her horse in Hickory Creek or tore across the ranch on her Suzuki three-wheeler. She was voted Future Farmers of America Sweetheart her freshman year, and though she smiled sweetly as she accepted the title, she was also a fiercely competitive girl who couldn’t stand to lose. For this reason, she adored her mare, Super T Sails—Te for short—who always delivered victories in the arena. “When I first got on Te, I just won and won and won,” Ashley said. She scoffed at ladylike equestrian events such as Western Pleasure, which Tasia competed in, where girls had to “sit proper” while loping their horses around the arena. “I like to compete in the rough-going, fast stuff,” said Ashley. “Te’s a real go-go horse—always hyped up and ready to run because she’s race-bred. I like to ride her on days when she’s crazy, so I can get on her and just go.”

Tasia was a different sort of restless. She was eager to see the world but was too young to have a driver’s license, and she spent her time hoping that her fledgling modeling career would take her to Houston again, or maybe even Paris. She was a striking girl with hazel eyes and the perfect tan who had left behind the days of gangly girlhood, having become the sort of young woman men from out of town turned to admire. But she seemed blithely oblivious to such things as she ran barefoot around her parents’ ranch, spending her spare time braiding her horse’s mane or deer hunting with her father or practicing her horse whispering. (For the latter, she would put one hand over her heart and one hand over the horse’s, leaning close to commune.) She made extra money helping her father with his taxidermy and bird-hunting business; he paid her a dollar for each pheasant or quail or chuckar he gave her, and she skinned the birds clean. “You just clip out the backbone and scoop the guts out,” Tasia said cheerfully. Then she stopped and laughed at herself. “It’s funny—at school, I’m Little Miss Perfect, and at home, I skin birds and ride.”

Tasia and Ashley were popular at Llano High School, in part because they walked the line between the girls who belonged to 4H and the girls who wouldn’t be caught dead wearing mud-caked ropers. They dressed in Abercrombie and Fitch instead of Wranglers, and they often asked their mothers to make the two-hour drive to the mall in Austin so that they wouldn’t have to dress too “country.” They did everything together, whether it was cheerleading, track, cross-country, or basketball, and though their running for rodeo queen at the same time may have strained their friendship, they didn’t let it show. Privately, they worried; Tasia dreamed one night that the pageant was actually a cheerleading competition in which only she and Ashley were trying out. But rather than begrudge each other for running, they did what best friends do: Tasia slept over at Ashley’s, and the two girls lay by the edge of Hickory Creek and stared up at the stars, talking excitedly about the summer trip they were taking with Ashley’s father to Cozumel. Before the pageant, they went to Kingsland and had their bellybuttons pierced—a blood pact of sorts for the future.

Jessica was once close friends with Tasia, and her scrapbooks are filled with old snapshots of the two of them posing in Halloween costumes and blowing out candles at birthday parties and standing arm-in-arm at Fiesta Texas beneath the words “Friends Forever.” They were not so different when they were younger, both loving horses and loving to ride. When Jessica spent the night at Tasia’s house, they would get spooked by the glassy-eyed twelve-point bucks and stuffed mountain lions that lined the walls. Now there was an awkward unfamiliarity between the two. They began to drift apart in the seventh grade, when Tasia made the cheerleading squad and Jessica did not. Three years later they seemed the unlikeliest of friends, the sort of girls who could only have been confidantes before the concerns of boys and clothes and popularity intervened. Jessica was in the same grade as Tasia and Ashley, but a year younger in age; the year’s difference meant that Jessica wore braces and that her demeanor was one of girlish enthusiasm instead of studied cool.

At times, Jessica felt more comfortable on her horse than she did anyplace else, and in some ways she knew her mare better than herself. “When she was old enough to hold her head up, she rode with me on the saddle,” said her mother, Maxanne. “She rode before she walked.” Jessica did not live in a big stone house, as both Ashley and Tasia did, but in a double-wide manufactured home that Maxanne had decorated in a Southwestern theme with cedar bookshelves and Mexican blankets and concho-studded picture frames. Jessica’s bedroom was a shrine to horses: A wall full of horse posters (her Backstreet Boys poster had been relegated to a dark corner), a bookshelf of horse novels, another bookshelf of miniature model horses, a box of horse jewelry, and horse hangers in the closet. Even the bathroom’s toilet paper dispenser was fashioned out of horseshoes. Jessica’s hands were toughened from years of roping and ranch work, and she loved nothing more than running her mare bareback along the creek that ran cold and clear through her family’s land. Rather than sending her mare away to be trained by professionals for steep fees, as contestants often did, she had trained Princess herself.

“A horse is what you make of it,” Jessica said. “We paid five hundred dollars for Princess, and she’s the best horse you could ever have. Folks around Llano will argue with you and say you need three or four thousand dollars to buy a good horse, but you can’t ride papers and bloodlines.” She was driving her family’s ranch truck down a rutted dirt road that rambled past oak trees and prickly pear and fields of green milo. Sitting beside her was her friend Trish, whose two sisters had both run for rodeo queen in years past. The girls hummed along to a Faith Hill song on the radio while Jessica steered the truck toward pens that held two feral hogs she needed to check on. The song faded, and the radio began to blare: This Weekend! The Llano County Rodeo! Jessica gripped the steering wheel and sucked in her breath. “Are you nervous?” asked Trish. Jessica nodded her head vigorously. “I’ll be so nervous,” she said. “I just can’t be nervous at the gate, because Princess will act up and get prancy, and I can’t mess up at the rodeo.”

Five days before the rodeo, the horsemanship competition began as dusk fell across the arena west of town. Lookers-on straddled the backs of dusty pickups and sat alongside the chutes, hooking their legs around the arena’s white fence posts. The last contestant to arrive was Jessica, who stood beside her horse trailer in tears. Earlier that evening her mare had lost her footing as she stepped into the trailer, snagging herself on the lead rope as she fell. The rope had tightened into a noose around her neck, and Princess had struggled for air until Jessica’s stepfather, Ross Parker, found a knife to cut her free. The mare had fared well—only one hind leg was skinned—but Jessica was shaken. “I’ve had her for seven years, and she’s my best friend,” she said. “I can’t stop thinking what would’ve happened if Ross hadn’t cut her loose in time.”

The horsemanship competition required riders to perform a simple pattern: Each contestant was to lead her horse into the arena, mount, trot in a figure eight, lope her horse in another figure eight, back up a few steps, dismount in front of the judges, and lead her horse out of the arena. To score well, she had to show a mastery of riding, keeping the reins in one hand, her elbows down, her heels back, her horse in the right lead. Jessica had practiced the pattern again and again during hot afternoons in the back pasture, and she turned in a near-perfect performance despite her mare’s earlier fall. Kim, who had borrowed a horse, was jostled badly in the saddle. Tasia rode well but struggled with the mount. And Ashley, whom everyone expected to ace the pattern, found that Te was too eager to run. By all measures, Te was a remarkable horse: One barrel racer had offered Ashley’s father $50,000 for her, and Kelly Leifeste—after many teary conversations with his daughter—had declined the offer. But like her rider, Te hated to stand still. When Ashley dismounted in front of the judges that evening, her horse champed at the bit and stamped one hoof, prancing around until Ashley, flushed with embarrassment, reined her in. Any bets that Ashley would win the rodeo queen crown were now off.

The standout contestant of the night was Jennifer Myers, who executed a perfect pattern until the end, when the wind kicked up and knocked off her hat. Her father, Bert, had talked her into buying a new straw hat that would set off her auburn hair, and Jennifer had mistakenly bought one that was a quarter of an inch too big. Though she and her sister—the reigning rodeo queen, Stacy—had lined the hat with paper towels and duct tape, it had still gotten away from her. Jennifer was a shy girl who lived in the shadow of her sister’s glory in the rodeo arena, but the pageant provided the chance to prove she was an equally good rider. Her roping and riding commanded respect: Jennifer was the only contestant the other girls could all agree deserved to win. But she was hardheaded like her father, who pushed her to the limit. “I had her crying three nights out of the past two weeks,” Bert said of the riding lessons he had given her. “She was sitting there, saying, ‘I can’t do it,’ but I knew she could. I told her, ‘Get back on the damn horse and listen to what I tell you.’ She finally got the hang of it the other night and did it twenty times, perfect. I made her do it ten more times after that just to make sure.”

Jennifer and her sister were always flanked by a group of good-natured cowboys, men who worked for Bert or who roped with Bert or who were just friends with Bert. “It’s like I’ve got twenty dads always keeping their eye on me,” Jennifer said with a sigh. The Myerses were not wealthy people: Though descended from one of Llano County’s biggest landowners, A. F. Moss, whose vast holdings once included Enchanted Rock, Bert’s great-great-grandfather John Moss was killed for a $100 gold piece, and his descendants were cut out of any inheritance. They lived simply on a twenty-acre tract along the river where Bert traded horses. The fact that his daughter Stacy had won the rodeo queen crown last year signaled a sea change: The pageant coordinator, a cheerful blonde named Kathy Hussey, had made the contest more impartial by trying to use out-of-town judges and ensuring that ticket sales carried the same weight as the other three events. Wealthy parents could no longer buy the pageant, as had sometimes been done back when ticket sales counted more heavily.

On the afternoon of the rodeo parade, Jennifer and the other contestants lined up on Ford Street with the floats they had slaved over for weeks. “I’ll tell you what,” Bert said, chuckling. “Making one of these things could drive a man to drink.” Jennifer’s flatbed trailer carried a life-size chuck wagon and campfire, with a coffeepot brewing—complete with a wisp of dry ice wafting up like steam. Tumbleweeds and stuffed rattlesnakes lay beneath the wagon wheels, and a cattle brand cooled by the fire, along with an arrow that had missed its mark. But the showpiece was an enormous granite rock: The Myerses had built it out of stucco, beat it soundly with a baseball bat until it was craggy, and then scratch-coated it gray. Jennifer sat on top of the float in a sparkly black-and-gold top, grinning. Kim’s float sported a papier-mâché bull that snorted dry ice. Tasia’s had scarecrow cowboys and a working windmill, Ashley’s a bucking chute, and Jessica’s was draped with saddles. “Don’t forget,” David Hussey, the pageant coordinator’s husband, cautioned the judges. “Whatever you decide, you’ll be breaking four little girls’ hearts.”

The weather that Friday afternoon was muggy and oppressive, and locals who were setting up folding chairs on the town square eyed the gathering storm clouds. Llano businesses had closed early that afternoon for the parade, and the square was jammed with boys tossing firecrackers, their fingers sticky with snowcones and popcorn, and women who smoothed their hair and touched up their makeup in the humidity. At four o’clock exactly, just as the parade was entering the square, the downpour began. It was not a light spring rain but a torrential thunderstorm that soon pelted onlookers with dime-size pieces of hail. A soaked Boy Scout troop ran for cover under the gazebo. The Llano High School cheerleading squad dashed past, soaked to the bone, as did the Stonewall Peach Jamboree girls, shivering in pink formal dresses that clung to them. “This is the pits,” said one woman with a hand on her hip. “I was born and raised here, and every parade day it rains.” Bringing up the rear was Jessica, her float already soggy and wind-torn. Some of the other contestants had wisely sought cover, but Jessica stood out in the rain, clutching her hat as her makeup ran, waving at the crowd through the storm.

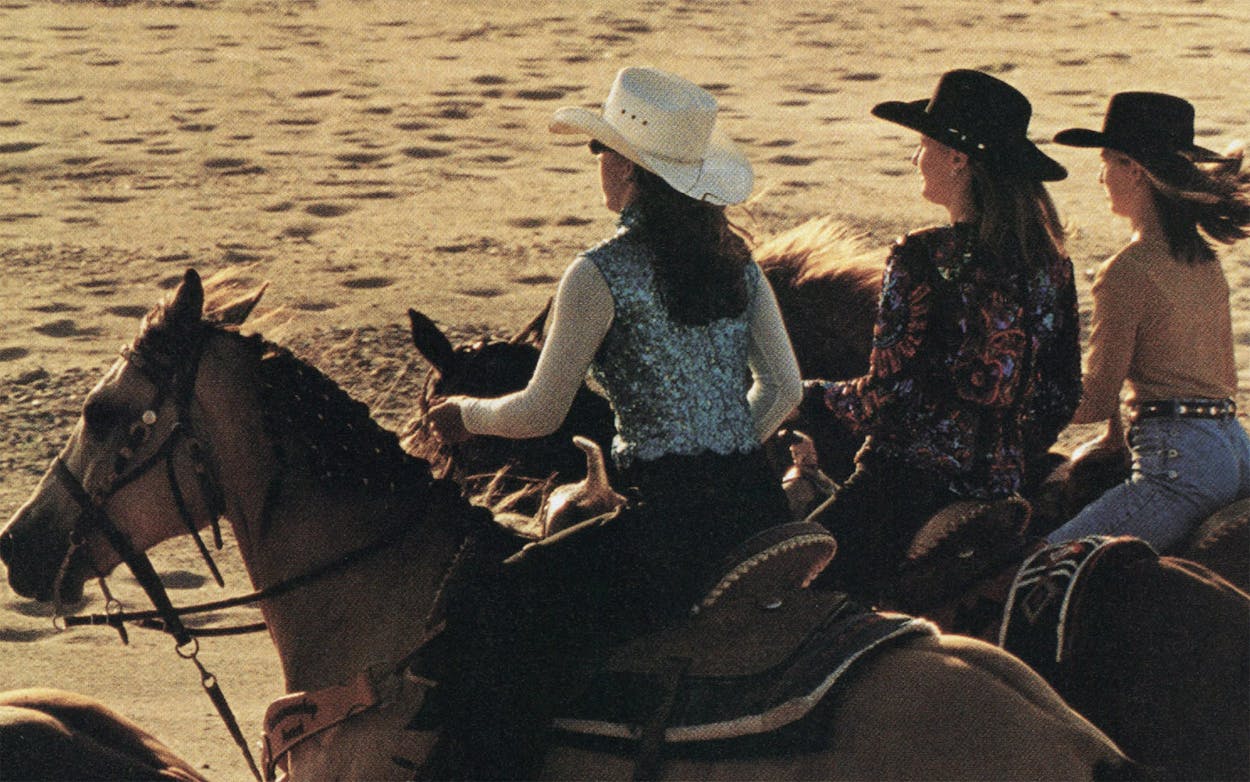

The rodeo began with bowed heads and a prayer of thanks for the soaking rain, which in this parched stretch of Texas was an inconvenience worth suffering. Storm clouds had skittered off to the east and a cool wind blew off the river. The stands were crowded with thousands of people from Llano and surrounding counties: towheaded children, lip-locked teenagers, women with dirty-blond hair in ultratight Wranglers, and everywhere, men in creased blue jeans, starched snap-front Western shirts, and white straw hats. The silver-buckled King of the Llano Rodeo and an early promoter of the event, 94-year-old Alex Hardin, sat in a wheelchair in the back of a pickup, smiling genially at the crowd. Glittering amid all the dirt and dust were the rodeo queen contestants, who sat astride their horses anticipating the moment, midway into the rodeo, when the crowning would take place. As the National Anthem faded, a cheer went up from the crowd and the first bronco came out bucking, his rider hanging on for dear life.

The rodeo queen contestants waited in the dirt-packed area behind the chutes, where cowboys traded stories while waiting their turn to ride. Jessica was anxious. She had worn her best riding clothes—a starched green button-down shirt and new blue jeans—but she looked plain beside the sequined girls whose every move glinted and gleamed under the lights. She had wanted the crown for so long, and now here it was: not victory, she sensed, but one long, awful moment of defeat she would have to suffer in front of the whole town.

“And now the moment you’ve all been waiting for,” the announcer said after team roping had wrapped up and the rodeo clowns had finished their slapstick act. “Let’s meet our new rodeo queen!” Jessica and the other girls raced into the arena on horseback, waving at the overflow crowd that was made up of just about everyone they had ever known. The girls lined their horses up in front of the stands and looked up at the crowd with frozen smiles. As the arena quieted down, the announcer began calling out the winners of each contest. “Ticket sales: Jessica Graham!” The other girls looked at Jessica, who nodded in gracious acceptance. She had sold nearly $5,360 worth of rodeo tickets, more than any other contestant in the history of the pageant. “Personality and appearance: Ashley Leifeste!” Jessica grimaced, then remembered that she was supposed to be smiling. “Horsemanship: Jennifer Myers!” Jessica wondered if she stood a chance next to Ashley and Jennifer. Now it all came down to her parade float. Her mare shifted uneasily beneath her.

“And parade float: Jennifer Myers!” The girls all turned to face Jennifer, who had turned crimson. “The winner of the Llano Rodeo Queen 2001 pageant is Miss Jennifer Myers!” Stacy, the reigning queen, stepped forward to place the tiara on her little sister’s hat as the crowd cheered.

Jessica loped her mare out of the arena into the darkness. If she cried, she did so privately. She rode back to her horse trailer to unsaddle Princess, but when she emerged, she looked more at ease than she had in weeks. After making her way through the crowd that had gathered around Jennifer, she gave the new queen her most heartfelt congratulations. And when Ashley reappeared in the arena a few minutes later racing barrels, her blond hair streaming behind her as she made it around one, two, three barrels perfectly, Jessica clapped as a cheer went up from the crowd. “She’s a real heartbreaker,” the announcer yelled over the din, explaining that Ashley had clocked in at 15.46 seconds—the fastest barrel racing time in the history of the Llano rodeo. After it was all over, the girls walked with the rest of the crowd down to the river to listen to Les Hartman and the Texas Thunder Band. Jessica, Ashley, and Tasia danced together as if they were the oldest and best of friends, for that one night at least.

Fourteen is an age not only of deep, private longings but of stubborn resiliency—and though Jessica had not imagined she would survive the humiliation of losing the rodeo queen pageant, she had. By the end of the night, she was flushed and in high spirits. She and the other girls would be getting back 5 percent of their ticket sales as a reward for raising so much money for the Llano County Community Center. That, plus the money she won in the pageant, was its own prize.

“That’s five hundred dollars! You know what five hundred dollars is?” Jessica said, breathless. “A horse!”

- More About:

- Longreads

- Horses

- High School

- Llano