On May 2, 1968, Staff Sergeant Roy P. Benavidez volunteered to come to the rescue of a twelve-man Green Beret patrol overrun by a thousand North Vietnamese infantry. The mission would prove to be, in Benavidez’s words, “six hours of hell.” Under heavy fire, he loaded eight wounded men onto helicopters not once but twice (because the first one was shot down). Benavidez survived a total of thirty gunshot, bayonet, blunt trauma, and shrapnel wounds. Believed dead when a crew arrived to retrieve him, he used his last ounce of strength to spit in the face of a doctor who was zipping him into a body bag—it was the only way he could prove he was still alive.

If you saw all of that in a movie, you’d think the deeds of the Lindenau-born, El Campo–raised Green Beret were beyond belief—Rambo in all-too-real life. You can read a more detailed (not for the squeamish) account of his heroics here, written by a veteran of the Iraq war. The U.S. Army’s official description, in the citation awarding Benavidez the Medal of Honor for his actions that day, is more subdued:

Sergeant Benavidez’ gallant choice to join voluntarily his comrades who were in critical straits, to expose himself constantly to withering enemy fire, and his refusal to be stopped despite numerous severe wounds, saved the lives of at least eight men. His fearless personal leadership, tenacious devotion to duty, and extremely valorous actions in the face of overwhelming odds were in keeping with the highest traditions of the military service, and reflect the utmost credit on him and the United States Army.

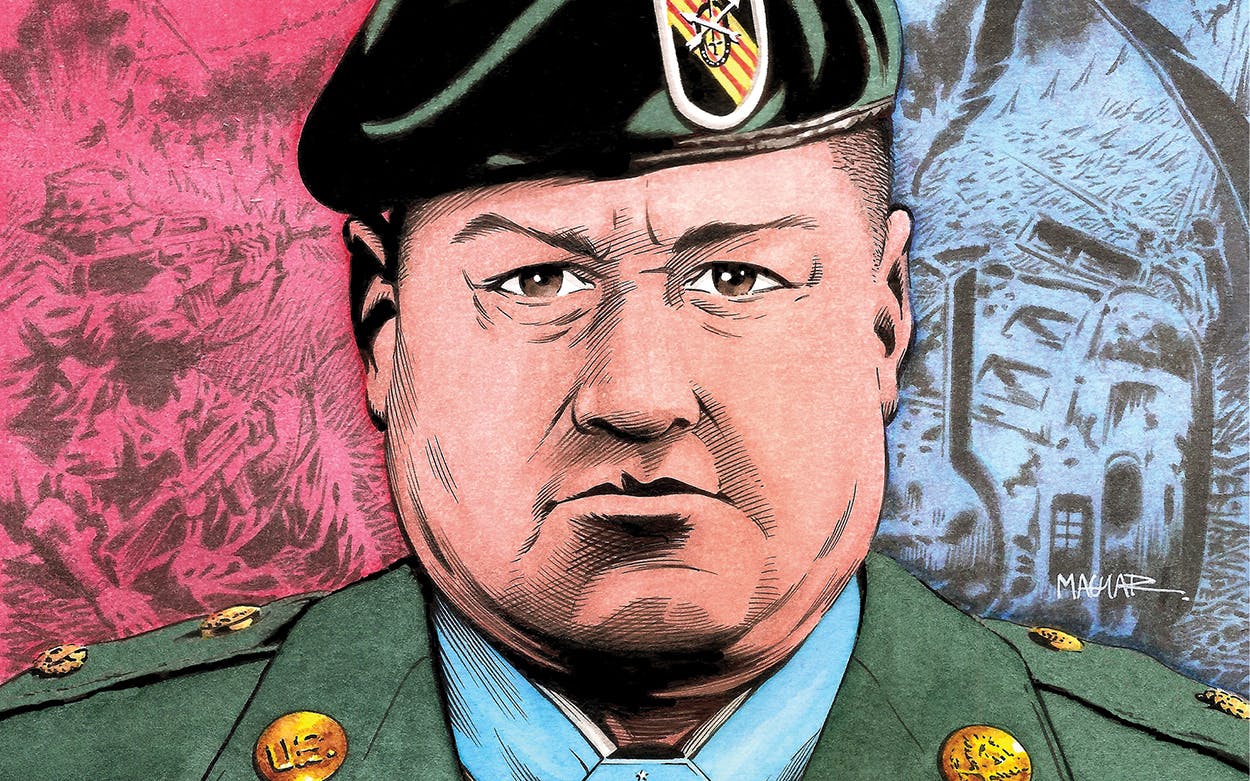

According to a recent Army Times article, Benavidez’s downright Herculean (even by Medal of Honor standards) acts were what guaranteed that he become the second serviceman to be the subject of a graphic novel in a series produced by the Association of the U.S. Army, right after World War I hero Alvin York. (You can read Medal of Honor: Roy Benavidez here.)

His name likewise lives on—he died in 1998—attached to parks, schools, fraternal lodges, scholarships, and a U.S. Navy supply ship. Back in March, the state of Texas renamed a stretch of Texas Highway 71 in his native Wharton County in his honor. But military historian and retired army officer George Eaton believes it’s past time to do even more to honor him: rename Fort Hood as Fort Benavidez.

John Bell Hood was a Confederate general who violated his oath to protect the U.S. Constitution by taking up arms against the Union. Even if one could forgive Hood’s support for secession and slavery, his skill as a leader is also hardly worth recognizing with a namesake Army installation. He is invariably described as one of the worst Civil War generals—overaggressive and in over his head. “(W)hile gallant in the early stages of the war, [he] accelerated the loss of Atlanta due to reckless assaults on an overwhelmingly superior Union force and wasted the Army of Tennessee in the Nashville-Franklin Campaign,” Eaton wrote in a 2015 Time magazine op-ed.

Continuing to honor Hood is a relic of a bygone era. In the run-up to World War I and during World War II, the army delegated to states the naming rights to all the new bases they were building. Lost Cause myth–infected Southern leaders chose the most prominent leaders from their states, and by that time, quality of leadership didn’t matter anymore. Generals like Bragg of North Carolina, Polk of Louisiana, and Hood of Texas were well-known; their incompetence in the field was forgotten.

Yet our state’s selection of Hood as a representative Texan is just as suspect as his military skill. Yes, he served in the U.S. Army here prior to the Civil War. (He received the first of many war wounds on Devils River, courtesy of a Comanche arrow through the hand.) But unlike fellow Confederate Albert Sidney Johnston, Hood never made Texas his home. It was a duty station first, and then—and this is key here—a Lone Star flag of convenience for his secessionist views. When his own native commonwealth of Kentucky declared its neutrality at the outbreak of the war, Hood renounced Kentucky in favor of Texas, and not because he intended to make our state his forever home after the war. He spent the last fourteen years of his life in New Orleans.

Contrast that with the inspiring, undeniably Texan story of Benavidez’s life. Born near Cuero as the son of a Mexican American sharecropper and a Yaqui Indian mother, he lost both his parents to tuberculosis by the time he was eight years old. He and his brother Roger moved in with his grandfather, aunt, uncle, and eight cousins. He attended school in his new hometown of El Campo only when he could squeeze it in between picking fruit and vegetables in fields from Texas to Washington State, working in a tire shop, or shining shoes at El Campo’s bus depot.

As with so many migrant workers, then and now, he dropped out of high school. At age seventeen, in 1952, Benavidez enlisted in the Army National Guard and went on active duty three years later. In 1959, he married Hilaria “Lala” Coy, earned his parachutist “jump wings,” and was assigned to the prestigious 82nd Airborne Division at Fort Bragg, North Carolina. There he qualified for Special Forces training and later served as a driver for General William Westmoreland in Germany.

Starved of educational opportunities as a civilian, Benavidez seized every challenge the military offered—not only learning combat skills, but also taking courses in oceanography and foreign languages, among others. Benavidez later joked that he was the only Hispanic soldier in the United States Army who spoke German with a Southern accent.

In 1965, he was deployed as a military adviser to the South Vietnamese army. That’s when his story took yet another too-unbelievable-for-Hollywood turn. While on patrol, Benavidez stepped on a land mine. Had it exploded, he likely would have died on the spot. Even as a dud, it maimed him—the charge erupted from the ground at a force of one thousand pounds per square inch and struck him in the back, ripping through cartilage, breaking vertebrae, and twisting, but not quite severing, his spinal cord. Back at Fort Sam Houston in San Antonio, he was told by Army doctors that his soldiering days were over. Not only that, they said, but he would never walk again. Through sheer force of will, Benavidez proved them wrong on both counts. He resumed his elite station and served a second combat tour in Vietnam, performing at a level seldom seen in modern warfare.

Benavidez’s war didn’t end even in peacetime. Between engagements speaking to schoolchildren about the value of education, Benavidez fought the federal government’s efforts to chip away at veterans’ benefits, his own included.

Eaton told me in a recent email exchange that since 2015 the Army has been under some light pressure to strike down the Dixie generals from their perches. His solution is to rename the bases after Southerners and Texans who didn’t take up arms against the government they had sworn to protect. His choice for Fort Hood is Benavidez, a man he believes rises above many other worthy Texan candidates. The impetus to make these changes has to come from where the names originated—the state governments or via a “popular groundswell.”

So, Texas, it’s up to you. Do we continue to honor a Texan of convenience who fought ineptly against the United States government in defense of slavery, or choose instead to bestow those garlands on a native-born son of the Coastal Bend, who, in the Army’s own words, through “fearless personal leadership, tenacious devotion to duty, and extremely valorous actions in the face of overwhelming odds” epitomized “the highest traditions of the military service, and reflect the utmost credit on him and the United States Army”?

This post has been updated to correct an error; General Bragg was from North Carolina, not Georgia.

- More About:

- Texas History

- Military