Among Dallas residents of a certain age, the Starck Club is often recalled with a mix of nostalgia and wonder: How did such a thing ever exist?

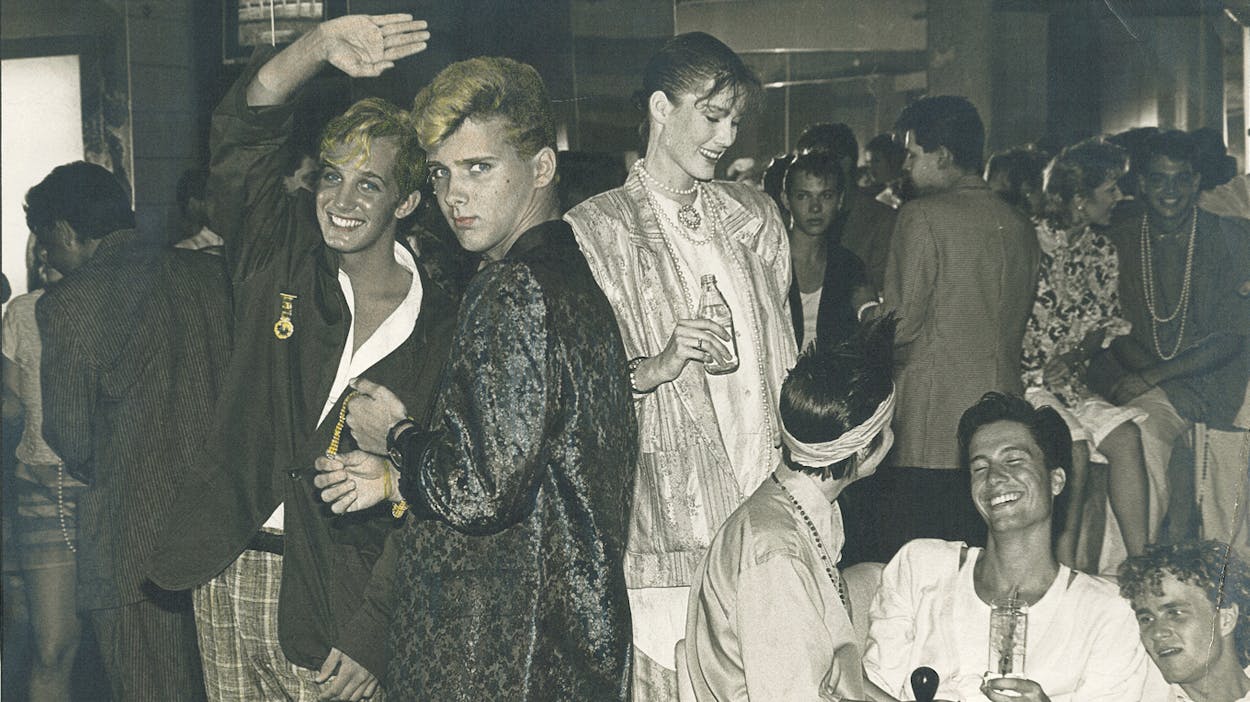

Opened in 1984 in a converted warehouse just north of downtown, the nightclub attracted oil-and-gas scions, Southern socialites, gay and cross-dressing men, and boldface names like Rob Lowe, George W. Bush, Princess Stephanie of Monaco and Maureen Reagan.

A year later, the club unexpectedly found itself at the center of the war on drugs when Ecstasy, which was used widely at the Starck, was declared illegal. Some have even argued that the club, which closed in 1989, gave birth to raves — the throbbing, Ecstasy-fueled dance parties that became popular in the 1990s. (Chicago and Detroit, where “acid house parties” took place in the late 1980s, are more traditionally credited.)

“We vote conservatively in Dallas, yet we love to break rules,” said Wade Randolph Hampton, a onetime Starck regular who in the 1990s tried to produce a feature film about the club. “And the Starck Club was just a safe place where you could finally be yourself in the city.”

Yet save for a handful of magazine articles and a little-seen 2011 documentary called “Sex, Drugs, and Design: Warriors of the Discotheque,” the history of the Starck Club has mostly gone untold — until now.

On Saturday, the Dallas filmmakers Michael Cain and Miles Hargrove premiered the documentary “The Starck Club” at the Dallas International Film Festival. (Cain was a founder of the festival in 2006, and served as president until 2011.)

Cain and Hargrove struggled to fit all of their material into a 95-minute documentary, and view the film as the first component of what may become a larger project that could include additional documentaries as well as a fictional film or television series.

“The 1980s, it was a decade of real change,” Cain said. “Conservatism was coming into the country in a much larger way because of Reagan, and the war on drugs was starting. There was greater sexual freedom, but AIDS also was entering the picture.”

Cain said that the Starck Club, the first “mixed club” in the city that appealed equally to gay and straight patrons, became the ultimate symbol of all of those changes and cultural contradictions.

Cain first attended the Starck Club in 1985 when his then-girlfriend’s brother, who had heard about the place from his hairdresser in Arkansas, was visiting Dallas and insisted they check it out.

“There wasn’t any of the social media ways of getting the message out, but what they had was this hairdressers’ network,” Cain said. “The hairdressers in Dallas and the surrounding states would tell everyone who sat down on their chair about the club.”

He first tried to tell the story of the Starck Club in a fictional film, which he wrote in the mid-1990s. At the Sundance Film Festival in the 1997, he learned that Hampton was shopping a script based on the Starck. Neither project came to fruition, but Cain remained fascinated with the subject. After his documentary “TV Junkie” premiered at Sundance in 2006, he returned to the idea of a documentary about the club, with Hampton as a producer and music supervisor, and Hargrove, a cinematographer and editor, as co-director.

Part of the challenge of making “The Starck Club,” the filmmakers said, was persuading the club’s principals to revisit the era. Many, including the founder Blake Woodall, have gone on to more traditional careers. (Woodall works for his family’s Richardson, Tex.-based company, which makes oven range hoods.) It took nearly two years of interviewing former club denizens before someone was able to put the filmmakers in touch with the club’s Paris-based designer and namesake, Philippe Starck.

“He started reliving his frustrations from that time,” Hargrove said. Starck, as evident in the film, felt his vision was compromised by the club’s investors, who insisted that he scale back costs.

“The Starck Club” is likely to please those who lived through the era — and prove eye-opening for those who did not. Cain and Hargrove make a strong case that Dallas had more cultural influence than is usually acknowledged, especially when it came to the new wave music that was played at the club. (The film features interviews with D. J.s like Paul Oakenfold and Tommie Sunshine and bands like Book of Love.) They also correct the widespread misperception that the club folded shortly after a major drug bust in 1986; in fact, it remained popular for three more years before Woodall and his partners decided to close it. (Since 2010, a nightclub called Zouk has operated in the space.)

Cain is shopping “The Starck Club” to distributors. Hampton is working with the head of Sire Records, Seymour Stein, to develop a Starck Club label that will reissue some of the music played at the club.

“There’s this image of Dallas that it’s all big hair and big boobs and vacuous people,” Hargrove said. The Starck “was the first time that Dallas was put on the map for something else, something that was cool and ahead of the curve. That’s probably the reason why it still resonates with people to this day.”